|

2 LP -

6.35716 EX - (p) 1986

|

|

| 2 CD -

8.35716 ZA - (p) 1986 |

|

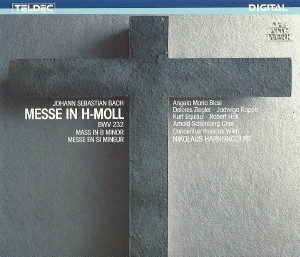

Johann

Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Messe in h-moll, BWV 232 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Kyrie |

|

17' 42" |

|

- Kyrie - Molto Adagio/Largo

|

10' 31" |

|

A1 |

- Christ

|

5' 16" |

|

A2 |

- Kyrie - Alla breve

|

2' 55" |

|

A3 |

| Gloria |

|

36' 00" |

|

- Gloria - Vivace

|

6' 38" |

|

A4 |

| - Laudamus |

4' 07" |

|

B1 |

| - Gratias - Alla breve |

2' 37" |

|

B2 |

- Domine Deus

|

5' 56" |

|

B3 |

- Qui tollis - Lente

|

3' 01" |

|

B4 |

- Qui sedes

|

4' 47" |

|

B5 |

| - Quoniam |

5' 14" |

|

B6 |

- Cum Sancto Spiritu - Vivace

|

4' 18" |

|

B7 |

| Credo |

|

31' 30" |

|

| - Credo - (Alla breve) |

1' 53" |

|

C1 |

- Patrem

|

2' 05" |

|

C2 |

- Et in unum

|

5' 06" |

|

C3 |

| - Et incarnatus est |

2' 58" |

|

C4 |

- Crucifixus

|

3' 33" |

|

C5 |

- Et resurrexit

|

4' 27" |

|

C6 |

- Et in Spiritum

|

5' 12" |

|

C7 |

- Confiteor - (Alla breve)

|

3' 55" |

|

D1 |

- Et expecto - Vivace et

Allegro

|

2' 20" |

|

D2 |

| Sanctus |

|

4' 21" |

|

- Sanctus

|

4' 21" |

|

D3 |

Osanna, Benedicstus,

Agnus Dei et Dona nobis pacem

|

|

15' 24" |

|

| - Osanna |

2' 36" |

|

D4 |

| - Benedictus |

6' 42" |

|

D5 |

- Agnus Dei

|

5' 15" |

|

D6 |

- Dona nobis pacem - Alla

breve

|

2' 51" |

|

D7 |

|

|

|

|

| Angela

Maria Blasi, Soprano I |

|

Delores

Ziegler, Soprano II

|

|

Jadwiga

Rappe, Alto

|

|

| Kurt

Equiluz, Tenor |

|

| Robert

Holl, Bass |

|

|

|

| Arnold-Schönberg-Chor

/ Erwin G. Ortner, Leitung |

|

|

|

| Concentus Musicus

Wien |

|

| - Friedemann Immer,

Richard Rudolf, Hermann Schober,

Naturtrompeten in D |

|

| - Kurt Hammer,

Barock-pauken |

|

| - Robert Wolf,

Leopold Stastny, Traverflöten |

|

- David Reichenberg,

Marie Wolf, Sem Kegley, Oboe,

Oboe d'amour

|

|

- Erich Höbarth,

Alice Harnoncourt, Anita Mitterer,

Andrea Bischof, Peter Schoberwalter,

Walter Pfeiffer, Violine

|

|

- Karl Höffinger,

Helmut Mitter, Iwan Dimitroff,

Gerold Klaus, Silvia Iberer, Peter

Schoberwalter jun., Violine

|

|

- Johannes Flieder,

Kurt Theiner, Josef de Sordi,

Viola

|

|

- Herwig Tachezi,

Mark Peters, Violoncello

|

|

- Eduard Hruza,

Andrew Ackerman, Violone

|

|

| - Milan Turkovič,

Andrew Watts, Fagott |

|

- Herbert Tachezi,

Orgel

|

|

- Andrew Joy, Corne da caccia

|

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Gesamtleitung |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Konzerthaus, Vienna (Austria)

- aprile 1986 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer / Engineer

|

| - |

Prima Edizione

CD

|

Teldec "Das Alte Werk" -

8.35716 ZA - (2 cd) - 55' 29" + 53' 33"

- (p) 1986 - DDD

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

Teldec "Das Alte Werk" -

6.35716 EX - (2 lp) - 55' 29" + 53' 33"

- (p) 1986 - Digital

|

|

|

Bachs Messe in h-moll:

Nikolaus Harnoncourt im Gespräch

mit Manfred Wagner

|

Mr Harnoncourt,

you first recorded Bach's Mass in

B minor 18 years ago - are there

any significant differences in

your interpretation, not in

detail, but in your overall

conception of the work?

I am often asked about differences in

interpretation, because we have been

making music for a very long time with

the same orchestra, and our listeners

always find it interesting if we

return again to a work that we

recorded many years ago. They often

spot very pronounced differences and I

am questioned about them. Well, there

is bound to have been some physical

and musical development as far as both

I and rny orchestra

are concerned - we

have, after all, been actively engaged

in music-making for the past 40 years

- and because we have

never lapsed into routine, because we

have always attempted to discover the

origins of our ideas, a good deal has

in fact changed. We ourselves are

unable to explain or pin down these

differences because they are organic.

After all, ifone looks in the mirror

every day one does not notice the

changes in one’s face. I

do notice it when I

listen to old recordings, but this

only happens occasionally because we

are still very much orientated towards

the future. But there certainly are

some elements which are basically

different: Before the first

recording we involved ourselves very

thoroughly in the work. At that time

the new edition had just been

published and, in the sweat of my

brow, I read every single line of the

extensive critical commentary. We also

studied most thoroughly Ehmann’s

writings on the subject of Concertante

and Ripieno performers, i, e, the

large and small choirs, because he

repeatedly quotes examples from the

Mass in B minor. As

early as 1968 we experimented with

certain distinctions between different

sizes of choir. Ar that time we were

already very deeply involved in the

Cantatas. But in the case of the Mass

in B minor we felt that this was not

music for the Sunday Service, written

for the routine Lutheran liturgy in

Leipzig. Even though one should never

use the word routine in connection

with Bach, his Cantatas for Sundays

were composed for a purpose which

recurred every week. The Mass in B

minor is a work

that is a stumbling block both from an

artistic and a religious point of

view; it does not really fit

into any liturgy; nor, with its

sensuous piety, is it a piece of

Protestant church music.

This is why, on this occasion,

we used women soloists instead of

boys. It is, after all, known that

Bach did this, even though it was

frowned upon, that he was interested

in the attractiveness and the

difference between a fine boy’s voice

and a female voice, and that he

prefered to have women

rather than boys to sing certain

works. We therefore deliberately

departed from the boys’ choir in this

performance and used a mixed choir,

because we take the

view that women’s voices are just as

accurate, that they reproduce the

rhythmical structures and coloratura

just as clearly, but that they also

contribute the sensuous flair of

adults to the music. As far as I am

concerned - and probably also today’s

listener - this is an essential

element in the work and it is no

longer all that important whether the

ideal, historically accurate rendering

is by a boys’ choir a mixed choir. One

also has to bear in mind that the

average age of boys’ choirs at that

time was three to four years older: 17

years old boys still sang treble or

alto; consequently a modern boys’

choir is not the same as it was in

Bach’s day.

This is surely the most sigificant

change since that day, and I suspect -

since we made both decisions, first to

opt for a boys’ choir, and now for a

mixed choir, of our own free will -

that this reflects a development

within ourselves.

But you stuck to boys' choirs in

your recordings

of the Cantatas?

You must not imagine that we

were not content with the boys’

choirs. It is precisely

because of our increasing experience

with boys’ choirs that it became

easier to achieve works quality with

them. We would have had no difficulty

in producing an excellent performance

of the Mass in B minor with boys’

choirs. If we do not do

so, the reason is not that we consider

a boys’ choir to be limited and think

that we ought to change over to mixed

choir for that reason. The reason is

that there are two conflicting

approaches from the point of view of

the warmth of

sound, and we are of the opinion that

the “injection of Catholicism”

justifies a mixed choir. When I say

“Catholic”, I am really speaking more

generally of “mediterranean”

countries, where the zest for life is

closely linked to religion: in Italy

there is rejoicing in church; even

when church architecture and paintings

display martyrdom or other sad themes,

there is always rejoicing; in my view

this extends, albeit not as strongly,

right into the Alpine regions.

I think Bach’s Hungarian ancestor had

an influence on him, but also that his

intense study oi Vivaldi may well have

instilled in him a longing for the

South, as did the occasional journeys

from Leipzig to the Catholic Court at

Dresden. Bach repeatedly advised his

sons to visit Dresden to hear the

Italian operas that were performed

there.

Friedrirh Smend who supervised

the Urtext

of the New Baeh Edition, in particular,

and other musicologists have

expressed the

opinion that the

Mass in B minor comprises individual works

written between 1733 and 1739,

which Bach himself had compiled

into an autograph anthology, but

that the notion that it is

unified work resulted from a

romantic attitude. You, on the other

hand, take the view that the

argument founded on sensuousness

applies not merely to individual

parts, but to the whole work, so

that it can all be bracketed

togheter.

This Mass has a rnost varied history.

In the 19th century it acquired the

soubriquet “High Mass”

and it was customary to view

it as a monolithic block, a sacrosanct

unity. Then research discovered that

the manuscript was composed of several

pieces. In my opinion, when the New

Bach Edition reached the volume “Mass

in B minor”, they overstepped the mark

by referring to the work

as the “so-called” Mass in B minor,

while laying particular stress on the

fact that it was

pieced together in 1748/49. It could

not be disputed that Bach had made the

compilation himself, but it was looked

on as a kind of “gathering together”

at the end of his long life.

As far as I am concerned, the truth

which I have gathered from the work

itself lies somewhere in the middle:

It is quite obvious that parts of it

were written separately; it is equally

obvious that some parts, e. g. the

so-called “Missa”, the central

portion, and the Sanctus as well,

were entirely appropriate to the

Leipzig Lutheran church service and

were indeed composed for it. The

very people who discovered the

separate pieces and the compilation

of the Mass have repeatedly accused

Bach of having no thorough

appreciation of the words, of having

set secular cantatas to other words

with a certain degree of unconcern.

They also claimed that the Christmas

Oratorio had seen the light of day

in the same way. Parts of the Mass

in B minor are indeed reworkings,

for example the Gratias originated

in “Wir danken dir”, or the Agnus

Dei in “Ach bleibe doch, geliebtes

Leben”. As far as the Christmas

Oratorio is concerned, I could not

agree with these musicologists: the

material that Bach used was of high quality,

he just changed the texts with a

certain lack of concern. In

“Herkules am Scheidewege” (Hercules

at the cross-roads) a passage in

which the two sensual ladies attempt

to deflect him from the path of

righteousness was used for “Prepare

thyself Zion” in

the Christmas Oratorio. From this I

have coneluded that Bach made use of

two similar emotional situations,

with an exceptionally sensual one

being equated with one that is both

sensuel and religious, even though

the texts differ. But I do not

believe that Bach already had only

one valid use in mind when he set

the secular text.

The pairs of works - German and

Latin in the case of the Mass,

secular and sacred versions in the

case of the “Christmas Oratorio” and

the Cantatas - came close together

chronologically. I have concluded

from the music that Bach was working

on both texts at the same time.

Once he had used a theme for a

certain “secular” purpose, it was

immediately adapted by him for what

was for him its final

purpose. I think the

work may have come into existence in

the following manner: A nucleus

which took shape gave Bach the idea

of expanding this nucleus into a great

Mass. One suspects that he used the

musical models of the individual

elements of the Missa tota in South

German, Austrian and Italian Mass

compositions (Christoph Wolff),

which he may well have got to know

in Dresden. There is also

strong evidence that Bach did all he

could to forge the Mass into a

coherent whole. For example, the

Gratias adapted from the Cantata “Wir

danken dir, Herr” was reworked to

become the core of the work, and he

related the figure

which introduces the chorus so closely

to number symbolism, associating it

with the total number of bars in the

whole work, that I am led to the

conclusion that the Mass was conceived

as a whole. Then there is the

conceptual link: In the Gratias a very

pronounced gesture of gratitude is to

be observed, and the same setting is

used for the final movement of the

Mass after the Agnus Dei, miserere

nobis (Lamb of God, have mercy upon

us), the Dona nobis

pacem (Give us peace). There is an

immediate and obvious correspondence

between the two: peace and

thanksgiving are intimately linked. To

my mind this gives a different

significance to peace in the final

movement: thanks are given not merely

for the Glory of God, but also for

Peace. There is also another unusual

and interesting treatment of the word

“Peace“ in the Gloria.

There is always an element of the

heroic in the Gloria, and the use of

trumpets produces a kind of dominating

attitude. But the “Et in terra pax”

produces an entirely new sound: not

only is it centred on “peace” (pax),

but the word “pax” is always cried out

or shouted, suggesting the ardent call

of men who have not yet received that

which has been promised to them. The

combination of a most unusual way of

setting the words of peace with the

Gratias and the Dona nobis pacem

indicates a very strong connexion.

Your arguments

also indicate that you do not

agree with the nusicologists who

claim to have observed uneven

qualities

or indeed a lowering of quality towards

the end of the Mass.

I cannot accept that there is a

lowering of quality. I get quite

annoyed when such arguments are

produced, since nobody who employs

them has the equipment required to

judge the presence or absence of

quality. In the final analysis it is a

judgement on one’s own quality as a

listener. That also applies to the

individual movements of this work: I

can only look for the qualities which

the composer has introduced. For

example, you cannot apply to a

movement with the ultimate in

polyphonic compactness

or to one with a theme that

anticipates the romantic period the

criteria of “absolute” quality; that

is a question of standards.

But before one engages in such serious

accusations one ought to posess those

standards.

I noticed

during the rehearsals for the Mass

in B minor, that you take quite a critical

view of the New

Bach Edition. You consider

it to be incomplete in many

respects, and sometimes even to

proceed from false premises. Could

you give us a few concrete

examples? The layman thinks of

collected works as a kind of

immutable edition, a bible which

is not to be doubted in any way,

and now you, as an interpreter,

express your doubts about it.

I take a critical attitude towards any

interpretation ofa work. I would

prefer to get hold of as much as

possible without anyone else’s

interpretation and to work out my own

interpretations - but always remaining

aware of the fact that the results of

this interpretation are only valid for

myself, and that others may come to

different conclusions. Every edition

is also an interpretation by its

editor. The greater its claim to

objectivity, the more it annoys me

when the edition clearly indicates the

interpretations of its editor My

critical view of the Bach edition is

due to the fact that it contains very

serious errors. The Scotch snap rhythm

of the Domine Deus is mentioned

neither in the volume nor in the

critical commentary, yet the piece has

an entirely different character

depending on whether it is executed in

that way or not. ln the

autograph parts this rhythm is quite

clearly notated. In

the old Bach edition it was retained

at least for the flute part, though

not in the string parts. Apart from

that, it is an imposition on the

interpreter to have to read and study

a vast amount of material in order to

discover how the editor arrived at his

text. ln this edition the parts - i,

e. the performance material which was

either written out by Bach or else by

his closest associates and corrected

by him - have been virtually

disregarded, That

is unforgivable, since the tempo marks

and articulation are indicated on the

parts. The argument that the user can

glean this information from the

critical commentary is of doubtful

value, because I know of no user other

than myself who does this. When

I have read a critical commentary I am

usually in need of a holiday. It

should surely be possible to

incorporate the information required

for the Aufführungs-praxus

in the main volume

and to dispense with the highfalutin’

padding.

May we examine this with the aid

of a concrete example, the "Domine

Deus" to which yon have already

referred? This is essentially a

question of the Scotch

snap rhythm which, as you

have stated, was indicated, at

least in part, in

the old Bach edition. As far as I

am concerned, it

its a serious corroboration

of the fact that a piece ok

knowledge which, albeit

only in part, is accepted as being

definite,

can be

omitted without any reason being

given for its

omission. What is the pratical

significance of this?

Here I should say that in the old Bach

edition it was not in the body of the

text either, but there is a reference

in the critical commentary to the

effect that in the first bar the flute

has an inverted Scotch snap.

In terms of

practical execution this means the

following: If I knew nothing about

this so-called Scotch snap, I would

play the descending semiquavers in

the second half of the bar specially

long; they would express a kind

ofintensitied sigh, because the

underlying main rhythm, the quavers,

represent an inverted sigh. This

means that long sighs would be

subdivided into short sighs, and

these sighs would, according to all

knowledge of Aufführungspraxis

and our musical inclination, be

played particularly weightily, so that

the resolution of the sighs would be

particularly light and short. But

here exactly the opposite is the

case: The sighing note is written

short and the resolution is weighty.

This has the result of making the

sigh more aggressive. In the

nomenclature of Bach’s day the

appropriate affects were described

as varying from “pert” to “very

intense”; certainly there is a

hightening of intensity, but at the

same time a lightening of the mood;

it is rather less tragic; the sigh

assumes an element of merriment. But

as it is only written in one bar one

has to ask oneself who is going to

play it and when is it to played? I have reached the

conclusion that it is intended for

all parts, including the second

violin and the viola, even when it

is not indicated in the flute part

or any other part, e. g. in Bar 27.

In this bar the

rhythm of the first violin is

written without the Scotch snap, the

only parts in this edition for which

it is written are the second violin,

which plays this rhythm for the

first time, and the viola. I think that in

rising chains of sighs, as with the

flute part in Bar 10, this rhythm is

not appropriate, but only where a

restricted ascent is attempted. In

the second half of Bar 8 and in Bar

9 there are sighs in the orchestra -

first and second violins and viola -

that are quite obvious; they recall

the end of the flute phrase in Bar

2. In the following bar these sighs

are continued in diminution, as it

were, by the flute (Bar 10). At the

beginning the sighing figure of the

flute is almost a chain,and this

gives considerable variety to the

vocabulary of this movement, which

makes great use of sighs or -

without wanting to imply any

interpretation - of grace notes or

suspensions and, in my view, makes

the rhythm much more colourful and

pronounced.

Variety is one

of your key words, because there

are a number of passages in your

interpretation where concords

which occur in the same

articulation are resolved or

changed in the spirit of Bach.

A tendency has developed during the

last 150 years for orchestras, and

indeed string quarters or even duos,

in a word right down to the smallest

combination possible, to play in a

completely unified style, just as

though four musicians or one hundred

musicians were all saying exactly

the same thing at the same time.

“Parallel passages” or “analogous

passages” - the existence of which I dispute - are

played in exactly the same way as a

matter of principle; if the

composer, as is often case with

Bach, but also with Mozart, writes

these passages with differing

dynamics, rhythm or articulation,

this is considered an “error” or a

mistake on the part of the composer,

and there is a tendency to correct

such passages. There are some

examples of this in the New Bach

Edition. It is my view, which I

derive from the musical aesthetics

of that period, and from the music,

the texts, the autographs of the

17th, 18th and sometimes even the

19th century, that composers were

concerned to give each part the

maximum individuality, that is to

say to have as little uniformity as

possible, but as much as was

necessary. On occasion that goes as

far as producing an impressionist

form of notation, i. e. every part,

taken on its own, looks illogical,

and only when they play together

does the superimposition of

differing articulations produce a

superior articulation which the

listener cannot fully take in, but

which is felt to be rich and

complex, even though it cannot be

understood in detail.

I noticed during the recording

that you provided two

significant, indeed dramatic

proofs of this: on the one

hand you placed the two

sopranos apart from each other

which, as far as I was

concerned, made yhe different

qualities of their voices

properly audible for the first

time; until then they had

always been inextricably

enmeshed; on the other hand

you argued that Bach always

orchestrated correctly. That

was said with reference to

those researchers who persistr

in talking of errors.

Regarding the positioning of

the sopranos: Fortunately we started this recording

with the first Kyrie. Originally we

placed the singers in the

traditionalway, that is to say first

soprano, second soprano, alto,

tenor, bass, that is to say in

descending voice parts. But it

became clear that whenever the two

soprano parts crossed, they combined

into a single part. This is

particularly obvious in Bars 62/63

or 67/68 of the Kyrie. That is why I tried to make them

more distinct, by selecting the

voices, by giving each of the

soprano parts a discernible colour

Then I had the idea of separating

them physically, since the soprano

voice is the one that is most easily

located. We took a risk, but it

worked from the word go. Today I cannot understand

why I did not

think of doing this sooner; I am

convinced that it is the right thing

to do. Of course theconsequence is

that the soloists must be similarly

arranged, because that is how one

can tell that if in four-part

writing the second soprano

occasionally has the top line, the

first soprano in the preceding solo

passages came from somewhere else.

This confirmed us in ourview that

this is not only beautiful, but that

it is also absolutely essential,

because it really gives us all five soloists. We

have all three female voices and it

is important, particularly with

reference to the phrases before and

after, that the soprano voices

should be heard to come from

different locations.

Do you think

that this was historically the

case as well?

I am sure of it, otherwise Bach

would not have stipulated in

four-part choruses which sopranos

should sing. It also emphasizes the

fact that it is a dialogue. I can

imagine Bach separating them

spatially even further apart. We

know, for example about the St.

Matthew Passion, that with each

version of the work he placed the

choirs further and further apart.

We also know that he often performed

motets with double choirs. Here

religious attitudes play a role: the

voices came not from one place, but

were spatially distributed, so that

they seemed to come

from everywhere. I

even think that what we have done is

just a first step by

comparison with what was done in

historical Aufführungspraxis.

Incidentally, in King’s College also

the choirs are separated on account

of the construction of the nave, and

it is staggering how well they sing

together simply because they are

accustomed to it.

By taking note of this fact

and of the question of Bach's

orchestration you have lifted

the problem of balance, which

has also been repeatedly raised

in connection with Mozart, to a

new level. It is not merely a

matter of individual producing

sounds at the

same time, but

also

of balance within the context,

such as ornaments in the Domine

Deus,

which have to be

followed up by the other chorus

parts.

lt also happens repeatedly in the

great choruses that individual groups

of instruments such as flutes,

trumpets, oboes, high strings, low

strings, chorus, on occasion the three

high chorus parts are pitted against

the three low chorus parts. The

material therefore passes from one

part to another and it seems to me to

be very important that its

articulation shoud be maintained and

that every single element should be

recognizable on its journey, so that

all can join in emotionally in

executing it.

With regard to Bach’s orchestration: I

have always wondered how it

happens that when these works are

performed today by modern orchestras,

some instruments simply get completely

lost at certain points and become

inaudible. I call it “mush” - all one

can hear is a splendid mishmash; it

may be harmonious but it is also

incromprehensible. The use of

historical instruments is a real

revelation; there are no trumpet

choirs smothering the flutes or oboes;

that is a matter of dynamic spread.

The old flutes, for example, have two

functions in which they are immeasurably

superior to modern flutes. One of them

is this: whenever they come into

contact with the oboes or strings,

they make an enormous difference to

their tone colour. You get the same

effect with certain types of fruit: if

you mix raspberries and red currants,

their flavour changes. It

is similar in the case of flutes:

although they cannot be heard, they

make the oboes sound quite different.

And where they have a life of their

own they are audible, no matter how

many instruments are playing. When

using modern instruments one

has to employ artificial means

if one wants to

achieve anything remotely resembling

the effect of historical instruments.

You have always taken an

interest in historial instruments,

but

this is something that you have

discovered in practice.

Here one must take account of what has

now become the self-evident

basis of Aufführungspraxis.

A tenuto note must be recognizable as

such - more often than not it is

indicated as such by the composer or

the score makes it clear - but

rebounding to long notes in order to

create a space for the rest of what is

going on is the be-all and end-all of

this style of playing, because it

ensures clarity.

A not insignificant contribution to this question

is made by the performer himself,

because

in rehearsal you demand a close

adherence to the forms of sequences,

analogies or figures,

which may appear confusing in

the score:

strangely enough, the instrumentalists

have adopted this and play, at

least this is how

it seems

to me,

with a different

kind of awareness, they play with

keener hearng. Does

this also apply to

the chorus?

Yes, absolutely, I always ask the

chorus to listen to the orchestra and

to apply the results in a similar

manner to their singing, and the

reverse is also important. I always

try to link these two aspects as

closely as possible together. It makes

quite a difference if every player

realizes that a figure which occurs

throughout the Kyrie is a gesture of

supplication, and the fact that this

has been recognized as such in Western

music for many centuries is probably

connected with physical imagery. If

one is urgently asking for something

one drops to one’s knees, tugs at

garments, and this gesture of

supplication has an element of

tugging, even when translated into

music.

This is pratically materialist

conception of music: the meaning

of something being

presented figuratively.

The figurative is an important element

of music, which consists not just of

notes and sounds or the interpretation

of texts; it can also reproduce

gestures very graphically.

I have

noticed that when you rehearse

complex materials you do not refer

very often to the subject matter,

but if you

do, you use powerful imagery,

such as "sacred intoxication"

(Cum sancto spiritu). This

means that you appeal to emotional

functional, material of physical awareness, which

creates an images for the

musicians, so that

they do not feel themselves to

be encumbered by clichés.

It is very

important that everyone involved in

this great undertaking should

be fully aware of his own role. This

could be done on a much more

profound spiritual level, but then

we would have to take the whole

ensemble into a

retreat for two month before the

performance.

The question is: would

it have this effect? As things

are now it can

be perceived with the senses and

immediately appreciated.

That is

correct, and it enables the individual

to use his own imagination: it does

not limit his own ideas, and

although he is guided towards the

concept he is not also compelled to

interpret it himself.

Can we go back to the written

parts? are they of any help? are

there any slurs or phrase marks

which suggest that Bach jimself

was aware of these problems of

interpretation?

Certainly. In the introduction to

the first Kyrie there is a

continuing insistence, and at the

same time the symmetry

is quite obvious.

Bach creates an upper part out of

the quavers which are not slurred

and continues it, and this upper

part employs the gesture of

supplication. The symmetry of the

lower parts is slightly impaired by

the slurs. Bach seems to have felt

that was going too far in the long run,

because in Bar 19 he wrote in all

four parts for flutes and oboes G

sharp - D - C sharp, A sharp - B, F sharp - E

sharp, and then another slur B - A

sharp, which is not to be found in

the New Bach Edition, although it is

in all parts written out by him,

then a slur A - G sharp half-way

through Bar 20, which is also

contained in all the parts. In

my view this slur has undoubtedly been

omitted as a result of a certain

schoolmasterly attitude, because it

was thought to be an error on Bach’s

part. But this is precisely where the

strings play the gesture of

supplication, and this is suddenly

resolved by brilliant inconsistency in

that Bach writes

slurs in two places where

they would not have been expected to

occur. I think we can take it for

granted that Bach would not have made

the same mistake in four different

parts. The interesting sequence of

events indicates to me that Bach did

it quite deliberately. Incidentally,

he is historically not the only one to

do this sort of thing: throughout the

18th century great composers

repeatedly did the same. In that way

special attention is drawn to a

rnotif.

In

this type of inconsistency

perhaps also what distinguishes

the really great masters from

every-day composers?

Is it Bach's use of colour

that distinguishes him from

diligent students of counterpoint?

Yes, precisely. I would even go

further than that: good composers can

take the listener along very

complicated paths without causing him

any kind of discomfort. Composers of

genius deliberately mislead: each

individual note leads consistently to

another note or to several other

notes. But the listener’s expectations

are not met, and that produces a

rninor sensation. All

composers make some use of this

device: interrupted cadences are also

used by lesser masters. But the

sophisticated way of keeping the

listener in suspense even in the

smallest phrases or figures and

demanding his attention - in a rnanner

of speaking “offending” him in a

highly intellectual way, by not

letting him hear what he

expects - only the truly great

composers are masters of that art.

The tempi are central

to collaboration with the

performers and also to the

rnaintenance of control which we

have already touched upon. The

Bach edition is of little

assistance in this respect,

because the full score contains

only very few tempo markings. Are

the tempi

in the parts correct?

In all probability Bach added

the parts for the front desks to the

dedicatory copy of the

“Missa” (Kyrie and Gloria); these

parts are preserved in the Dresden

Library and constitute the main source

of our recording. He kept the

duplicate copies for his performances,

and they have got lost.

The reverse happened with the Sanctus:

he lent a set of parts to Count Sporck

in Bohemia, and they also got lost.

But the copies, which Bach had kept in

Leipzig, are preserved. The

comparatively large number of parts

originally prepared gives an

indication ofthe comparatively large

number of players involved (at least 2

to 3 musicians playing from a single

part); the Catholic

Chapel at Dresden was well supplied

with musicians.

We have used 6 each of first and

second violins, 3 violas, 2 cellos, 2

doubles basses (violone).

The tempi are Bach’s own, as they are

taken from the parts. If I did not

know that Bach had written “adagio”

and “molto adagio” against the four

introductory bars of the Kyrie, which

is sung by a large number of voices, I

would probably take it at a much

faster speed. These wonderfully slow

bars are like the threshold of a

gigantic building, they put me in mind

of the gates of a baroque palace four

metres high, although the people who

walk through them are only 1.80 m

tall. The first

tempo indication to be found in the

score is “largo” in Bar 5, at the

beginning of the great Kyrie movement.

It is very helpful to

have “adagio” or “molto adagio”

preceding it, because it enables me to

see the relationship to the movement

which follows it. The tempo in the

Sanctus has always presented great

problems, particularly with regard to

its mood. The heavenly choir of

angels, announced in the Preface, the

prayer which precedes the Sanctus, a

“never-ending Amen”, is portrayed in

two movements. (The Gloria, too, is

the song of the angels on Christmas

Nights) The three upper choral parts

and the three lower choral parts

constitute two separate choirs which

are clearly distinct from one another.

But it is very difficult to discover

the tempi at which the Sanctus is to

be expressed: is it to be a song of

rejoicing, or is it to be, as it were,

spoken? A further element contributing

to uncertainty is the fact that many

of the parts bear the mark “alla

breve” (though, it should be noted,

not in the score, not even a hint of

it), because many of Bach’s works have

been handed down both with and without

“alla breve” markings. This is the

case here, just as it is in the first

movement of the Brandenburg Concerto

No. 1. There is a

tendency to take these passages too

slowly. I get the

impression that what Bach intended by

the Alla breve sign was “in the sense

of andante, certainly not too slowly”.

I take it to be a word of warning, of

encouragement, concerning the speed,

but not of emphasis. Movements headed

with the Alla breve sign fall within

the stylistic sphere of Palestrina:

even during the baroque period works

in the old polyphonic style were

notated in minirns,

but they were marked “alla breve”;

this old style managed to hold its own

by the side of the “modern” style,

because it was the “official” style of

Catholic Church music. Of course it

was often by - passed - fortunately, I

am inclined to say; here I am not

talking of the instruction “Alla

breve”, but of the sign,which was

obviously not used for alla breve but

which was merely intended as a warning

against being too slow.

But such conclusions are only

arrived at through practice...

...and by comparing many works, the

tempo markings of which have been

thoroughly studied. In Mozart’s works

this marking has a much more precise

function as an indication of speed

than it has with Bach.

Could this be

connected with the fact that Bach

war writing for the Church,

that for his

rnusicians he had to write

comparatively; he did, after all,

know his musicians and their

habits; he knew where they tended

to drag.

Yes, this also explains why it is

marked in certain parts. This might be

connected with the positioning of the

musicians; they frequently stood where

the acoustics were poor and where it

was well known that they had to play

briskly in order not to seem to be

dragging.

So this is worked out from the

point of view of Aufführungspraxis...

...absolutely. In

addition, when I have a

fiery tempo written in crotchets,

which is what the Alla breve sign

suggests to me, there must be no

thought of its relationship to the

“Pleni sunt coeli” at all. The tenor

entry in Bar 48 is a wellknown source

of anxiety, yet no tenor has ever

asked me about the speed, because it

arises quite naturally from the

crotcbets of the Sanctus. That is the

strongest musical argument, as far as

I am concerned. Many complicated

relationships have been produced out

of thin air, for example the triplets

in the Sanctus were turned into

quavers in the Pleni.

That proves once again

that a sensible edition which

satisfies the demands of practical musicians can only

be provided after great

practical knowledge acquired

over a long time.

Yes, of course. In any

case practising musicians, who are

after all also concerned that

musicological information should be

provided, should be

given a better hearing when such

editions are being prepared.

In other words, what causes the

complications is not you yourself

or your interpretation, but

essentially the demands of the

composer, because he uses a

different logic from that of the

pedantic musicologist.

Yes. I merely obey the composer’s

instructions, if I am

able to do so. It may also happen that

I cannot understand something; then I

will do the sarne as those whom I

criticise - but I cannot go against my

own convictions. But I do not reach

this stage until very late in the day,

I try for as long as I can to allow

myself to be convinced that the composer

was right in his instructions.

In other words, the composer is

right as long as there are no counterarguments.

That’s it. But when he has really

convinced me, then I will be his

champion and will go to the barricades

for my convictions, if I have to.

And the rnusicians will follow

suit, since the thread of the

argument by which the composer has

convinced you is similar to the

steps which you will take to

convince your players.

Yes, it is comparable. And the harder

it is for me to be convinced, the

easieris it for me to convince the

players, because all arguments that

they present to me are those which I

have already countered in

myself.

This proves that this partnership

also acts as a control.

Yes, and it

may also happen that, while we are

working, I am myself corrected by the

players.

Professor Manfred Wagner is a present

Head Professor for the History of

Culture and Ideas at the Academy of

Applied Arts in Vienna. Bruckner

specialist and an expert ou

interpretation, he is involved at the

moment with the development of

objectifiable methods in reception

research. Manfred

Wagner has written many books, radio

broadcasts and television films.

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|