|

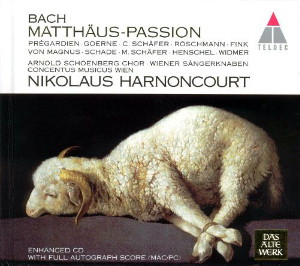

3 CD -

8573-81036-2 - (p) 2001

|

|

Johann Sebastian

Bach (1685-1750)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Matthäus-Passion, BWV 244 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prima

Parte

|

|

70' 43" |

|

| - Chorus (1,2): Kommt, ihr

Töchter, helft mir klagen - (Soprano in

ripieno: O Lamm Gottes) |

6' 46" |

|

CD1-1 |

| - Evangelista: Da Jesus

diese Rede vollendet hatte |

0' 40" |

|

CD1-2 |

| - Choral: Herzliebster Jesu,

was hast du verbrochen |

0' 44" |

|

CD1-3 |

| - Evangelista: Da

versammleten sich die Hohenspriester ... /

Chorus (1,2) / Evangelista / Chorus (1) /

Evangelista |

3' 04" |

|

CD1-4 |

| - Recitativo (Alto 1): Du

liber Heiland du |

1' 00" |

|

CD1-5 |

| - Aria (Alto 1): Buß und Reu |

4' 47" |

|

CD1-6 |

| - Evangelista: Da ging hin

der Zwölfen einer |

0' 35" |

|

CD1-7 |

| - Aria (Soprano 2): Blute

nur, die liebes Herz |

4' 37" |

|

CD1-8 |

| - Evangelista: Aber am

ersten Tage der süßen Brot ... / Chorus

(1) / Evangelista / Evangelista / Chorus

(1) |

2' 19" |

|

CD1-9 |

| - Choral: Ich bin's, ich

sollte büßen |

0' 52" |

|

CD1-10 |

| - Evangelista: Er antwortete

und sprach |

3' 06" |

|

CD1-11 |

| - Recitativo (Soprano 1):

Wiewohl mein Herz in Tränen schwimmt |

1' 16" |

|

CD1-12 |

| - Aria (Soprano 1): Ich will

dir mein Herze schenken |

3' 42" |

|

CD1-13 |

| - Evangelista: Und da sie

den Lobgesang gesprochen hatten |

1' 09" |

|

CD1-14 |

| - Choral: Erkenne mich, mein

Hüter |

1' 04" |

|

CD1-15 |

| - Evangelista: Petrus aber

antwortete |

0' 58" |

|

CD1-16 |

| - Choral: Ich will hier bei

dir stehen |

1' 01" |

|

CD1-17 |

| - Evangelista: Da kam Jesus

mit ihnen zu einem Hofe |

1' 47"

|

|

CD1-18 |

| - Recitativo (Tenore 1,

Chorus 2): O Schmerz! (Chorus: Was ist die

Ursach') |

1' 44" |

|

CD1-19 |

| - Aria (Tenore 1, Chorus 2):

Ich will bei meinem Jesu wachen - (Chorus:

So schlafen unsre Sünden ein) |

5' 30" |

|

CD1-20 |

| - Evangelista: Und ging hin

ein wenig |

0' 44" |

|

CD1-21 |

| - Recitativo (Basso 2): Der

Heiland fällt vor seinem Vater nieder |

0' 47" |

|

CD1-22 |

| - Aria (Basso 2): Gerne will

ich mich bequemen |

4' 37" |

|

CD1-23 |

| - Evangelista: Und er kam zu

seinen Jüngern |

1' 13" |

|

CD1-24 |

| - Choral: Was mein Gott will |

1' 07" |

|

CD1-25 |

| - Evangelista: Und er kam

und fand sie aber schlafend |

2' 24" |

|

CD1-26 |

| - Aria (Soprano 1, Alto 1,

Chorus 2): So ist mein Jesus nun gefangen

... Chorus / Chorus (1,2) |

4' 54" |

|

CD1-27 |

| - Evangelista: Und siehe,

einer aus denen |

2' 20" |

|

CD1-28 |

| - Choral: O Mensch, bewein'

dein Sünde groß |

5' 57" |

|

CD1-29 |

Seconda

Parte

|

|

91' 32" |

|

| - Aria (Alto 1, Chorus 2):

Ach! nun ist mein Jesus hin! (Chorus: Wo

ist denn) |

3' 48" |

|

CD2-1 |

| - Evangelista: Die aber

Jesum gegriffen hatten |

1' 02" |

|

CD2-2 |

| - Choral: Mir hat die Welt

trüglich gericht't |

0' 47" |

|

CD2-3 |

| - Evangelista: Und wiewohl

viel falsche Zeugen |

1' 07" |

|

CD2-4 |

| - Recitativo (Tenore 2):

Mein Jesus schweigt zu falschen Lügen

stille |

1' 05" |

|

CD2-5 |

| - Aria (Tenore 2): Geduld! |

3' 21" |

|

CD2-6 |

| - Evangelista: Und der

Hohepriester antwortete ... / Chorus (1,2)

/ Evangelista / Chorus (1,2) |

1' 53" |

|

CD2-7 |

| - Choral: Wer hat dich so

geschlagen |

0' 48" |

|

CD2-8 |

| - Evangelista: Petrus aber

saß draußen ... / Chorus (2) / Evangelista |

2' 25" |

|

CD2-9 |

| - Aria (Alto 1): Erbarme

dich meine Gott |

6' 03" |

|

CD2-10 |

| - Choral: Bin ich gleich von

dir gewichen |

1' 03" |

|

CD2-11 |

| - Evangelista: Des Morgens

aber ... / Chorus (1,2) / Evangelista |

1' 46" |

|

CD2-12 |

| - Aria (Basso 2): Gebt mir

meinem Jesum wieder! |

2' 59" |

|

CD2-13 |

| - Evangelista: Sie hielten

aber einen Rat |

2' 10" |

|

CD2-14 |

| - Choral: Befiehl du deine

Wege |

1' 04" |

|

CD2-15 |

| - Evangelista: Auf das Fest

aber ... / Chorus (1,2) / Evangelista /

Choru (1,2) |

2' 22" |

|

CD2-16 |

| - Choral: Wie wunderbarlich

ist doch diese Strafe! |

0' 47" |

|

CD2-17 |

| - Evangelista: Der

Landpfleger sagte |

0' 16" |

|

CD2-18 |

| - Recitativo (Soprano 1): Er

hat uns allen wohlgetan |

1' 04" |

|

CD2-19 |

| - Aria (Soprano 1): Aus

Liebe will mein Heiland sterben |

4' 51" |

|

CD2-20 |

| - Evangelista: Sie schrieen

aber noch mehr ... / Chorus (1,2) /

Evangelista / Chorus (1,2) / Evangelista |

1' 52" |

|

CD2-21 |

| - Recitativo (Alto 2):

Erbarm es Gott! |

1' 05" |

|

CD2-22 |

| - Aria (Alto 2): Können

Tränen meiner Wangen |

6' 03" |

|

CD2-23 |

| - Evangelista: Da nahmen die

Kriegsknechte ... / Chorus (1,2) /

Evangelista |

1' 10" |

|

CD2-24 |

| - Choral: O Haupt voll Blut

und Wunden |

2' 09" |

|

CD2-25 |

| - Evangelista: Und da sie

ihn verspottet hatten |

0' 57" |

|

CD2-26 |

| - Recitativo (Basso 1): Ja!

freilich will in uns das Fleisch |

0' 39" |

|

CD2-27 |

| - Aria (Basso 1): Komm,

süßes Kreuz |

6' 14" |

|

CD2-28 |

| - Evangelista: Und da sie an

die Stätte kamen ... / Chorus (1,2) /

Evangelista / Chorus (1,2) / Evangelista |

3' 32" |

|

CD3-1 |

| - Recitativo (Alto 1): Ach,

Golgatha |

1' 32" |

|

CD3-2 |

| - Aria (Alto 1, Chorus 2):

Sehet, Jesus hat die Hand (Chorus: Wohin?) |

2' 41" |

|

CD3-3 |

| - Evangelista: Und von der

sechsten Stunde an ... / Chorus (1) /

Evangelista / Chorus (2) / Evangelista |

2' 15" |

|

CD3-4 |

| - Choral: Wenn ich einmal

soll scheiden |

1' 11" |

|

CD3-5 |

| - Evangelista: Und siehe da,

der Vorhang im Tempel ... / Chorus (1,2) /

Evangelista |

2' 39" |

|

CD3-6 |

| - Recitativo (Basso 1): Am

Abend da es kühle war |

1' 36" |

|

CD3-7 |

| - Aria (Basso 1): Mache

dich, mein Herze, rein |

5' 52" |

|

CD3-8 |

| - Evangelista: Und Joseph

nahm den Leib ... / Chorus (1,2) /

Evangelista |

2' 25" |

|

CD3-9 |

| - Recitativo (Soprano 1,

Alto 1, Tenore 1, Basso 1, Chorus 2): Nun

ist der Herr zur Ruh gebracht (Chorus:

Mein Jesu, gute Nacht!) |

1' 44" |

|

CD3-10 |

| - Chorus (1,2): Wir setzen

uns mit Tränen nieder |

5' 12"

|

|

CD3-11 |

|

|

|

|

| Christoph

Prégardien, Tenor

(Evangelista) |

Elisabeth

von Magnus, Contralto II

(Ancilla II, Testis I) |

|

Matthias

Goerne, Bass (Jesus)

|

Michael

Schade, Tenor I |

|

Christine

Schäfer, Soprano I (Ancilla I,

Uxor Pilati)

|

Markus

Schäfer, Tenor II (Testis II) |

|

| Dorothea

Röschmann, Soprano II |

Dietrich

Henschel, Bass I (Judas,

Petrus, Pontifex I, Pilatus)

|

|

| Bernarda

Fink, Contralto I |

Oliver

Widmer, Bass II |

|

|

|

| Wiener

Sängerknaben / Norbert Balatsch,

Chorus master |

|

| Arnold Schoenberg

Chor / Erwin Ortner, Chorus master |

|

|

|

| CONCENTUS MUSICUS WIEN (with

original instruments) |

|

| -

Erich Höbarth,

violin |

-

Herlinde Schaller,

viola |

|

| -

Alice Harnoncourt,

violin |

-

Herwig Tachezi,

violoncello |

|

| -

Andrea Bischof,

violin |

-

Dorothea Guschlbauer,

violoncello |

|

| -

Karl Höffinger,

violin |

-

Eduard Hruza,

violone |

|

| -

Helmut Mitter,

violin |

-

Andrew Ackerman,

violone |

|

| -

Anita Mitterer,

violin |

-

Alberto Prat-Muntadas,

violone |

|

| -

Walter Pfeiffer,

violin |

-

Robert Wolf,

transverse flute |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter,

violin |

-

Reinhard Czasch,

transverse flute |

|

| -

Anneke Bik,

violin |

-

Michael Schmidt-Casdorff,

transverse flute |

|

| -

Annelie Gahl,

violin |

-

Marie Celline Labbé,

transverse flute |

|

| -

Barbara Klebel,

violin |

-

Wolfgang Plank,

recorder |

|

| -

Veronica Kröner,

violin |

-

Elisabeth Baumer,

recorder |

|

| -

Maria Kubizek,

violin |

-

Hans Peter Westermann,

oboe |

|

| -

Maighread Mc Crann,

violin |

-

Marie Wolf,

oboe |

|

| -

Sophie Schafleitner,

violin |

-

Annette Spehr,

oboe |

|

| -

Christian Tachezi,

violin |

-

Wolfgang Plank,

oboe |

|

| -

Irene Troi,

violin |

-

Milan Turkovič,

bassoon |

|

| -

Gertrud Weinmeister,

violin |

-

Eleanor Froelich,

bassoon |

|

| -

Lynn Pascher,

viola |

-

Herbert Tachezi,

organ |

|

| -

Gerold Klaus,

viola |

-

Johann Sonnleitner,

organ |

|

| -

Ursula Kortschak,

viola |

|

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Jesuitenkirche-Universitätskirche,

Vienna (Austria) - maggio 2000 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer / Engineer

|

Wolfgang Mohr / Martina

Gottschau / Martin Sauer / Michael

Brammann

|

Prima Edizione

CD

|

Teldec Classics "Das Alte

Werk" - 8573-81036-2 - (3 cd) - 70' 43"

+ 60' 54" + 30' 38" - (p) 2001 - DDD

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

The

"great Passion"

|

Ever

since Mendelssohn's

legendary revival of the

work in 1829, the St

Matthew Passion has

been hailed as the greatest

setting of the Passion story

in western music, with the

Berlin-based academic Adolf

Bernhard Marx, for example,

actively championing the

work in the press at the

time of its revival and

describing it as the

"greatest work by our

greatest composer, the

greatest and most sacred

work of music of all

nations".

Even within Bach’s own

lifetime, the performance of a

setting of

the Passion story on Good

Friday was the highlight of the

musical year in Leipzig,

alternating under a council

regulation of

1724 between the two main

churches of St Thomas’s

and St Nicholas's.

And even at this date

the St Matthew Passion

was known

as the "great Passion" to

distinguish it from the four

other Passions that Carl

Philipp Emanuel Bach

ascribed to his father in

the Obituary that he wrote

with Johann

Friedrich Agricola. When

Anna Magdalena Bach, for

example, added the words

"for the great Passion” to a

continuo

part, everyone in the Thomaskantor's

house knew which work she

was referring to.

Bach's

first large-scale vocal work

for Leipzig, following his

appointment as Thomaskantor

in 1723, was his St John

Passion, which he

wrote for Lent 1724 - the

tempus clausum

between the First Sunday in

Lent and Palm Sunday. The St

John

Passion is believed to

have been followed in 1727

by the St Matthew

Passion, a setting of

sections of St Matthew's

Gospel for double chorus.

Four years later came the St

Mark Passion, the

music for

which has unfortunately

not survived. These

large-scale Passions were

performed at Vespers

on Good Friday and far

surpassed anything

previously heard in Leipzig.

In

contrast to Hamburg, which

was something of a

stronghold of the German

Passional tradition, Leipzig

continued until 1720 to

follow the lead laid down by

Luther's

musical adviser Johann

Walter, with Walter's

own Passion being

performed

in a revised version by the

Nicolaikirche Kantnr,

Gottfried Vopelius. In

this version, the verses

from the Bible were

declaimed according to very

strict formulas. Churchgoers

in Leipzig had little

experience of the oratorio

Passion that had evolved

under the influence of the

italian cantata and of

opera, with its recitatives

and arias, although in 1717

one of

Telemann’s Passions -

probably the Brockes

Passion - was

performed in the

artistically ambitious, but

musically out-of-the-way

Neue Kirche.

And Bach's immediate

predecessor as Thomaskantor,

Johann

Kuhnau, wrote an oratorio

Passion based on St Mark’s

Gospel for perrormance at Vespers

on Good Friday in 1721. But

Bach's

Passions, and especially his

St Matthew Passion,

set new standards.

The Passion for double

chorus

The uniqueness of the St Matthew

Passion rests not only

on its monumentality

but

also on its overall

conception, a conception

based in turn upon its use

of a double chorus. Bach

himself drew explicit

attention to this feature of

the work

when he added the words ”a

due cori” to the title-page

of Part Two. It

may well have been Christian

Friedrich Henrici’s ("Picander's")

libretto that encouraged

this approach on Bach’s

part, inasmuch as the text

represents a contemplative

dialogue between the

daughter of Zion and the

faithful. These two

participants in the dialogue

» the "Daughter of Zion" and

the "Faithful" -

are also found in the famous

Passion libretto

by Barthold Heinrich Brockes

first published in Hamburg

in 1712.

Even so, none of the many

other composers who set this

text - Keiser, Handel,

Mattheshon, Telemann or Stölzel

- hit upon the idea of using

a double chorus.

Even Bach himself appears to

have been struck by this

idea only when already

engaged on the compositional

process and, indeed, it may

have been only belatedly

that he decided to pursue it

to its logical conclusion.

Numbers such as ”Ach! nun

ist rnein Jesus

hin” (30) and "Sehet,

Jesus

hat die Hand" (60) are cast

in the form of a dialogue

with the solo voice

alternating with the choir,

whereas in the opening

chorus, even the individual

voice - the "Daughter

of Zion” representing Jerusalem

or the Lord's Bride - is

set as a four-part chorus. In

adopting this approach, Bach

laid the foundations for the

work’s

overall design, with the

double chorus as an

essential element in his

musical conception. In

more than half the total

number of movements, the

executants are drawn equally

from Chorus I and

Chorus II

- they are also, of course,

combined together as a four-part

ensemble in some of the turba

choruses, the chorales and

in the arrestingly vivid

chorale fantasia "O Mensch,

bewein dein

Sünde

groß"

(29), which Bach had

previously used as the

opening chorus of his St

John

Passion. Only when he

revived the St Matthew

Passion in 1736

did he take over this

chorale fantasia into this

last-named work, transposing

it in the process from E

flat major

to E major.

In

reviving the work in 1736,

Bach appears to have taken

this polychoral design a

stage further: according to

a report by the sexton at St

Thomas's,

Johann

Christoph Rost, the Passion

that year was performed

“with both organs", in other

words, each of the two

choruses had its own

continuo. The present

recording reflects this

division. To quote Nikolaus

Harnoncourt: "The

performing material was

written out in part by Bach

himself and shows exactly

what he wanted played and

sung and by whom. It

would have been completely

impossible to have the vocal

solos of Chorus I and

Chorus II

sung by the same singers, as

they are in the choral parts

of their own individual

Chorus.

And it would be equally

impossible for the

instrumental solos such as

the two gamba solos to be

performed from a single

position or to have a single

continuo player accompanying

both Choruses:

the parts are carefully

written out and figured,

with only rests in numbers

allotted to the other

Chorus." With each Chorus

having a solo ensemble of

its own, the present

recording adopts a

consistent approach to the

dialogue principle, while at

the same time underlining

the aspect of space as an

integral part of the work.

The textual basis of the

Passion

Whereas the St John

Passion, with its

numerous revisions, was

something of a work in

progress and the St Mark

Passion was largely

based on existing material,

the St Matthew Passion

is essentially an original

work that is unified in its

conception, Three layers of

text may be distinguished

here; passages from the

Bible, strophes

from existing hymns and

free verses.

Large sections of Picander's

lyrically contemplative

verses are inspired by the

Passion sermons of the

Rostock theologian

Heinrich Müller

(1631-75), who taught at

Rostock University and

also served as the ciiy's

superintendent. Müller's

input is particularly

significant inasmuch as

his theological writings

were well represented in

Bach’s library, so that it

may have been the Thomaskantor

himself who drew

Picander’s attention to

the relevant passages. If

so, the St Matthew

Passion would be an

important example of the

close collaboration

hetween Bach and one of

his librettists, a

closeness that we can

almost certainly assume to

have existed with a number

of his parodies, too.

A brief

example may serve to

illustrate Picander’s

dependence

on Müller.

The passage is taken from

the bass recitative, no.

64:

Müller

Am Abend / da der Tag Kühle

worden war /

kam die Sünde

der Menschen erstlich

ans Licht /

am Abend nimmt sie

Christus

wieder mit sich ins Grab

/ daß

ihr nicht mehr gedacht

werde. Um

die Vesper-Zeir kam

das Täublein

Noah zum Kasten / [...]

Picander

Am Abend da es kühle

war,

Ward Adams Fallen

offenbar,

Am Abend drücket

ihn der

Heyland nieder.

Am Abend kam die Taube

wieder,

Und trug ein Oel-Blatt

in dem Munde.

Müller's

text was published in

Frankfurt am Main as early

as 1688 and is entirely

within the tradition of

Lutheran orthodoxy, being

based in many respects on

the writings of the north

German reformer Johannes

Bugenhagen. In comparison,

Picander’s paraphrases

reveal a shift of emphasis

in the direction of

Pietistic attempts to spread

the Good Word.

Yet even in the St

Matthew Passion, of

course, Bach ascribed

overriding importance to the

words of the Bible, which he

took over unaltered. It is

an importance, moreover,

that could almost be seen as

anachronistic when set

beside the modish Passion

librettos of poets such as

Christian Friedrich Hunold

and Brockes.

The exceptional status of

the Biblical text is clear

not least from the fact that

in his 1736 score Bach

entered the whole of the

Evangelist's text in red inlk.

Equally untypical of

contemporary settings of the

Passion story are the

numerous four-part chorales

that may be thought of as

representing the

congregation and that

similarly stress the

liturgical framework.

The "musical" Passion

Even though Bach's

Passions were performed

within the context of church

services,

the local burghers almost

certainly regarded Vespers

on Good Friday as a good

night out, with the "musical

Passion", as it was known,

providing the evening's

principal attraction. As

early as 1721 one of Leipzig's

theology students, Gottfried

Ephraim Scheibel, wrote: "I

recall that a Passion was to

be performed at a particular

place on Good Friday both

before and after the sermon.

I am certain that people

would not have come to

church so early and in such

large numbers on account of

the preacher alone. lt was

presumably because of the

music."

Bach’s music was certainly

unique in what it had to

offer its listeners. In no

other work did he have such

comprehensive recourse to

the whole formal repertory

of contemporary music: not

even opera - the most

prestigious of Baroque

genres - had anything

remotely comparable to offer

in terms of its formal

variety.

The chorale and the various

ways of setting a cantus

firmus were by their very

nature alien to the world of

opera, but so, too, was

polyphony, a procedure that

is one of the distinguishing

features of Bach's

music. A few examples may

suffice

to illustrate the

multilayered nature of Bach's

language.

Even the monumental opening

chorus is symptomatic of the

scale of the work: it goes

far beyond the annunciatory

function of a traditional

exordium

(”Listen

to the Passion...”),

unfolding on three levels

with its two Choruses and

cantus firmus choir. At the

same time, Picander’s

threnody, which is cast in

the form of a dialogue ("Kommt,

ihr Töchter"),

has been set as a funeral

march in the style of a

French tombeau.

Its

key of E minor was defined

by the Hamburg-based writer

on music, Johann Mattheson,

as "designed to make the

listener very pensive,

profoundly thoughtful,

downcast and sad, but in

such a way that he still

hopes to be consoled".

Combined with this threnody

is the G major chorale, O

Lamm Gottes,

unschuldig, to which

Bach repeatedly returns in

the course of the musical

argument. With its reference

to the innocent Lamb as

Ruler in Zion, this opening

chorus also provides the

work with what Christoph

Wolff has termed a

"theological and

eschatological heading",

creating an overarching

structure whose sense of

tension is not resolved

until the final chorus.

The work's overall structure

is unique, and Bach scholars

have long been fascinated by

its underlying symmetry.

Central to the structure,

both musically and theologically,

is the sequence of numbers

from 46 to 49, in other

words, from the chorale "Wie

wunderbarlich ist doch diese

Strafe" to the soprano aria

"Aus Liebe will mein Heiland

sterben”. Nikolaus

Harnoncourt follows the

German musicologist

Friedrich Smend in seeing in

this section "the central

message of the work",

a section around which

choruses and arias are

grouped that are "musically

attuned to each other to the

highest degree".

At

the same time, it would be

wrong to overlook the

processual and dramaturgical

element in this structure.

As before, it is the

Biblical account of Christ's

Passion that forms the basis

of Bach’s setting and

provides it with its common

thread.

For all its rhetoric, the

part of the Evangelist is

predominantly narrative in

style. A comparison between

the parallel passages at

"Und alsbald krähete

der Hahn" and the weeping

Peter at "und weinete

bitterlich" in the St John

Passion reveals that

the writing for the tenor

voice and continue is less rhetorically

intense. At the same time, Jesus's

words are clearly

distinguished from the

Evangelist's recitatives

and, in keeping with a

tradition dating back to the

time of Heinrich Schütz,

are accompanied by four-part

strings. They are thus set

apart in the truest sense of

the term, and it is

significant that Christ's

final words, "Eli, Eli, lama

sabachthani?", are sung

without this halo of

strings: Christ becomes man

at the moment of His death.

The turba choruses,

finally,

are fully integrated into

the dramatic process and, as

a result, take very

different forms and reflect

a whole range of musical

models extending from the

brief and brutally dissonant

interjection, "Barrabam", to

the extremely long final turba

chorus, "Herr, wir haben

gedacht".

As in his cantata arias, so

in the St Matthew

Passion, Bach was at

pains to vary the tonal

spectrum by means of

additional instruments, with

a solo violin, for example,

leaving its mark on the

famous lament, "Erbarme dich",

which takes as its starting

point Peter's remorse at his

denial of Jesus.

The way in which Bach set

the text here is a good

example of the extent to

which tradition and

innovation come together in

his musical

language.

His debt to traditional

procedures is clear from his

dependency on the musical

rhetoric of the 16th

and l7th centuries and from

the way in which he

interprets the text by means

of figures drawn from

musical rhetoric. Of

particular significance is

the exclamatio

at "Erbarme dich", with the

wide-ranging intervals in

the vocal line taken up by

the solo violin and

ornamented as figures that

may be interpreted as

suspirations or sobs. The

diatonic bass line,

meanwhile, depicts the

falling tears - the "Zähren"

of the text. These figures

are, of course, only one

aspect of music whose

principal Affekt -

to use a term borrowed from

the belief that specific

emotions were associated

with specific musical

elements - is determined

above all by the model of

the grieving siciliana.

Pictorial rhetorical figures

repeatedly leave their mark

on the musical textures,

regularly going beyond the

interpretation of individual

words. In

the chorale "O

Mensch, bewein dein Sünde

groß",

the musical substance is

determined in the main by

three figures: the sighlike

figures first heard in the

flutes and oboes,

the invocatory figures that

involuntarily suggest the

words "O Mensch" and

the cruciform llgure in the

oboes in bars 5-7.

It is

also worth mentioning finally,

Bach’s use of number

symbolism, a use which,

admittedly, has led to often

highly speculative

interpretations. The

situation is not always as

clear-cut as it is at the

question "Herr, bin ichßs?"

(Lord, is it I?),

which is repeated eleven

times before the twelfth

disciple, Judas,

answers in the chorale

immediately afterwards, "Ich

bin’s, ich sollte büßen"

(’Tis I

whose sin now binds Thee)

(no. 10).

The architectural structure

of the St Matthew

Passion is so

overwhelming in terms of

both overall conception and

musical detail that experts

and amateurs alike have

repeatedly been moved to

draw upon grandiose

comparisons. One of Bach's

19th-century biographers,

Carl Hermann Bitter, saw the

image of a "majestic

cathedral" rising up before

him when he heard the work,

while his successor Philipp

Spitta was likewise reminded

of "miraculous Gothic

buildings" when listening to

it. Today’s listeners may

react in more sober ways.

Yet, however inapposite the

comparison between Baroque

music and Gothic

architecture may seem from a

historical perspective, it

is symptomatic of the sense

of astonishment that we are

bound to feel at the almost

literally ungraspable

greatness of Bach’s

St Matthew Passion.

Wolfgang

Sandberger

Translation:

Stewart Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|