|

|

1 CD -

026 - (c) 2002

|

|

| Clavecin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Girolamo

FRESCOBALDI (1583-1643) |

Toccata

Seconda (1615) |

|

4' 39" |

1 |

|

Canzona

Quinta (1615) |

|

2' 24" |

2

|

|

Fantasia

Quarta, sopra doi soggetti

(1608) |

|

6' 09" |

3

|

|

Capriccio

sopra la Bassa Fiamenga (1624)

|

|

5' 32" |

4 |

|

Toccata

Settima (1627)

|

|

3' 00" |

5

|

|

Recercar

Primo (1615)

|

|

4' 54"

|

6

|

|

Canzona

Terza (1627)

|

|

3' 51" |

7

|

|

Toccata

Ottava (1615) |

|

1' 25" |

8 |

| Louis COUPERIN (1626ca.-1661) |

Suite

in Ré majeur |

|

12' 10" |

|

|

-

Prélude

|

3' 30" |

|

9 |

|

-

Allemande

|

1' 08" |

|

10 |

|

-

Courante

|

1' 46" |

|

11 |

|

-

Sarabande

|

1' 54" |

|

12 |

|

-

Gaillarde

|

1' 54" |

|

13 |

|

-

Chaconne |

1' 58" |

|

14 |

|

Passacaille

en sol mineur |

|

5' 03" |

15 |

|

Suite

en mi mineur |

|

7' 11" |

|

|

-

Prélude

|

1' 20" |

|

16 |

|

-

Allemande

|

3' 03" |

|

17 |

|

-

Courante |

1' 19" |

|

18 |

|

-

Sarabande |

1' 49" |

|

19 |

|

Pavane

en fa dièse mineur

|

|

4' 34" |

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Gustav LEONHARDT,

Clavecins |

|

- Clavecin italien de

Martin Skowroneck (Frescobaldi)

- Clavecin français d'Emile Jobin,

copie de Vincent Tibaut (Couperin)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Chapelle de l'hôpital

Notre-Dame de Bon Secours, Paris

(Francia) - febbraio 2002 |

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Alpha |

|

|

Recording Engineer

/ Editing

|

|

Hugues Deschaux |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

nessuna |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Alpha - ut

pictura musica | 026 |

1 CD - durata 66' 28" | (c) 2002 |

DDD |

|

|

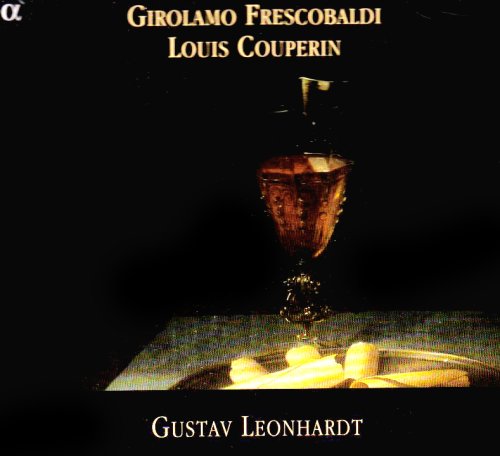

Cover Art

|

|

Lubin Baugin,

Nature morte aux gaufrettes

ou Le Dessert de gaugrettes,

Musée du Louvre |

|

|

Note |

|

Digipack

|

|

|

|

|

Lubin

Baugin (Pithiviers,

c.1610-1612 - Paris, 1663)

Still

life with wafers or The

Dessert of wafers,

c.1630-1635 (Oil on wood

panel, 41 x 22 cm)

Paris, Musée

du Louvre

Trained in the

Fontainebleau aesthetic, this

painter was attracted to the

sweetness typical of the

Parrna school, Whose influence

on his religious output is

patent. The model above all

models when it came to Holy

Families and Virgins with

Child, Raphael, lurks behind

his Madonnas, whose

sophisticated manner, taking

liberties with nature, plays

on a light palette with

accents both pastel and

resonant, calling Guido Reni

to mind. But his Italian tour

was for later in his career,

in the 1630s. In 1629, in

order to escape the ascendancy

of the tyrannical Paris guild,

this future academician (a

status he acquired in 1651)

first rose to the rank of

master-painter at

Saint-Gennain-ties-Prés, where

the abbey contained a

veritable reservoir of

European painting. Thus he

came into contact with Flemish

culture. His still lives, a

northern speciality, date from

this early period. With their

links to Caravaggism, the

inevitable point of reference,

they reveal a positive

artistic personality that was

already defying

categorisation.

On a table covered with a

slate blue, moiré damask

cloth, we can see, set out on

three different planes; a

pewter plate containing wafer

biscuits, protruding over the

edge of the table; a

straw-yellow wicker wine flask

surmounted by a stopper in the

form of a ducks head; a ridged

glass, in cristallo ‘à

la façon de Venise’, whose

deep conical bowl is supported

by a baluster with a mesh of

intertwined serpents, and

decorated by embossed picots,

tears of glass which emphasise

its edges. Coming partly from

a window, an abstract,

ambiguous light, throwing

discordant shadows, is

reflected on thesurface of the

glass, and on that of the red

liquid, which it irradiates,

and which thus takes on in

places a bronzed tint. In the

background, a stone wall built

of heavy quadrangular blocks

is interrupted by an opening

against which the goblet

stands out.

A eucharistic reading of this

painting, would be delusory.

Its intentions lie in the

direction of a formal

investigation for whic the

iconography becomes a mere

pretext. This approach,

clearly modern, aims to

identify the

interrelationships, structural

and geometric, volumetric and

spatial, and chromatic too,

between objects set out like

signs on a score. Economy of

means, sobriety, terseness of

discourse: understatement

reigns, with typically French

asceticism. Modesty and

reserve of the art of the

Paris region, which suggests

more than it states, banishes

excess, and keeps to

essentials. Through rigour and

control. Yet all of this is

nothing but illusion: the

equivocal use of lighting; the

rich, indeed exuberant Italian

decoration of the glass; the

complexity of this goblet‘s

relationship with the light;

the precarious position of the

plate; the contradictory

shadows; even the cheeky

expression of the duck with

its glassy eyes - all these

are sources of tension. Poetry

of silence, transparency,

limpidity, grace, skill in

harmonisation. Yes, all this

is present. But so are

angularities, dissonances,

dissimulation... ‘quirks’.

Under the semblance of order

and permanency, the fragility

of this equilibrium becomes

apparent. Art of the moment,

the work appears as a metaphor

for the culture of the

Baroque, an age in unceasing

movement, bubbling with

creativity, refusing fixed

paradigms. This protean

half-century resists

authoritarian, immutable

sedimentation, the cloak of

uniformity that acadernicism

and its chilly logic will soon

impose on all the arts.

Denis

Grenier

Department

of History

Laval

University, Quebec

Translation:

Charles Johnston

What is

the Grand Siècle?

With the touch

of blithe arrogance that

sometimes characterises them,

the French people tend to

reduce History to that of

France. Seeing themselves as

pioneers in all things, they

like to view the world from

the single vantage point of

their own doorstep.

Take what is emphatically

known as the Grand Siécle, for

example, which largely

summarises the contradictions

that the country regularly

comes up against. Fascination

for the splendours of

Versailles, and at the same

time criticism of social

inequalities. Admiration for

Louis XIV‘s implacable method

in bringing the aristocracy to

heel, and abhorrence of the

absolutist despot who strung

wars together as if they were

no more than dances in a ballet

de cour. But the French

are fundamentally proud of

what remains of their

heritage. It attracts millions

of visitors to France each

year. Tourism is an excuse for

everything...

So the Grand Siécle

refers to the reign of Louis

XIV, seen as Frances period of

political and cultural

pre-eminence. It was the

century of the Sun King and of

Versailles, its magnificent and

cultivated court frequented by

great men such as the

landscape gardener Le Nôtre,

the painter Le Brun,

dramatists Racine and Molière,

the composer Lully (renowned

for his operas), and the finest

poets, architects, military

strategists, philosophers and

scientists. In short, it was a

time of great minds, in which

everything was grandiose.

This definition is not

entirely false.

Nor is it completely true...

Crowned at Rheims cathedral on

7 June 1654, at the age of

sixteen, Louis XIV did not

wield full power until 1661,

after the death of the first

minister of France, Cardinal

Mazarin. From then on, he

ruled as an absolute monarch,

learning to use the arts,

literature and the sciences to

serve his political purpose.

‘A great sovereign, like a

great artist, is measured by

his ability to give shape to

the vague aspirations that his

contemporaries feel, sense and

imagine, but are unable to

achieve.’ Louis gathered

together the creative forces

that he found in his

entourage, made sure that

brilliant rivals such as

Nicolas Fouquet were out of

the way, and by developing the

Academies, was instrumental in

taking to its zenith every

form of expression that was

capable of enhancing his own

glory. In so doing, he

channelled artistic creativity

to his sole benefit, at the

risk of stifling it

completely, as with opera,

where only Lully was allowed

to present works on a theatre

stage.

Versailles was extremely rich

and active, but it must be

remembered that Baroque had

already been in existence for

several decades in the rest of

Europe. And it was in that

world of imagination and

artistic and intellectual

effervescence that musicians

such as Girolamo Frescobaldi

and Louis Couperin flourished.

It may not make much sense to

speak of Europe at the

beginning of the seventeenth

century, at least in the

modern acceptance of the term.

There had been no formulation

of an awareness of belonging

to the same community, no

questioning of the frontiers

that separate its different

nations. But there were

numerous exchanges, and styles

and techniques circulated

constantly, in the fields of

painting, music and the

theatre. Moreover, France and

Italy shared a love for

beautiful things. A watch

beaning an exquisite

painted-enamel miniature,

cabinets of finely carved

ebony, leather-bound books

decorated with motifs in gold

leaf, tapestries, costume...

everything in the arts made

this a ‘time of exuberance’.

But exuberance meant neither

superficiality nor excess. On

the contrary, ornamentation,

whether in architecture,

painting, furnishings, the

decorative arts or music,

steered clear of

grandiloquence.

The same may be said of

Frescobaldi's music.

Born in 1583 in Ferrara, a

prestigious city ruled by the

House of Este until its

incorporation into the Papal

States in 1598, Frescobaldi

studied music with the court

organist, Luzzaschi. At the

crossroads of Italian, Flemish

and French styles, Frescobaldi

immersed himself in the

different techniques of

counterpoint. And most

importantly, he experienced

the musical polemics of the

time, including the debates on

the best way of setting

literary texts to music which

preceded the first performance

of Monteverdi's first opera, L'Orfeo,

in Mantua in 1607.

In Rome, where he arrived in

the early years of the

seventeenth century,

Frescobaldi was taken up by

the wealthy and influential

Cardinal Bentivoglio, and when

his patron became a papal

nuncio he accompanied him to

Flanders. During that time his

Primo libro di madrigali a

cinque voci was

published in Antwerp by Pierre

Phalèse. On his return to Rome

in 1608, he brought out a book

of Fantasie for

harpsichord or organ, in which

he adapted the tradition of

vocal polyphony to the

keyboard. From then on, it was

instrumental music - or to be

more precise, music for the

harpsichord or the organ -

that gained the composer's

favour.

Frescobaldi was probably what

we would now call a virtuoso.

At the age of twenty-five, he

took up the position of

organist of St Peter's, Rome,

which he retained until his

death in 1643. All over Europe

his reputation steadily

increased. His works were

published, which was a

privilege, then republished

several times, which was an

even more obvious sign of an

influence that was to last for

several decades.

From 1615 onwards, he

published several sets of

works in which he confirmed and

developed the originality of

his style. In the Recercari

et Canzoni, which still

bear signs of the ‘old style’,

the instrumental destination

is as yet unspecified, while

the Toccate e partite,

illustrations of the

composer‘s ‘new manner’, are

explicitly attributed to the

harpsichord. The style is

different again in the Capricci

of 1624, in which he presents

various imaginative treatments

(capriccio means

‘whim’, ‘fancy’) of a

well-known theme, such as the

Flemish bass (bassa

fiaminga), which he may

have noted down during his

travels in 1607.

In 1628, Frescobaldi was

summoned to Florence to work

for the Grand Duke of Tuscany,

Ferdinando II. There he

returned to vocal music with

the publication of two books

of Arie musicali for

1-3 voices (1650). The ‘second

Apollo of our time’, as he was

described, enjoyed great

prestige, whence a salary that

was higher than that of any

other musician.

At the request of Cardinal

Francesco Barberini, a nephew

of Pope Urban VIII,

Frescobaldi returned to Rome

in 1634. The Barberini family

were probably the most

munificent patrons of the arts

that Rome had yet known,

influencing artistic creation

throughout the seventeenth

century. In their service,

Frescobaldi no doubt met other

major figures, including

Bernini, who was admired

throughout Europe, the

composers Kapsberger, Landi

and Michi, and the great

Jesuit theorist, philosopher

and musician Athanasius

Kircher. During that period,

he revised several earlier

works, including the two books

of Toccate, to which

he made additions in 1657. He

also published the Fiori

Musicali (1655), a

collection of organ pieces for

use in the Mass, dedicated to

his patron's brother, Cardinal

Antonio Barberini. During his

lifetime the composer was

admired as a paragon; in his

famous Response faite à un

Curieux sur le sentiment de

la musique d'Italie

(1639), the violist André

Maugars describes an office for

Lent that he attended in Rome.

‘The great Frescobaldi

conjured up all kinds of

inventions on the harpsichord.

It is not without reason that

the famous organist of St

Peters has acquired such a

reputation in Europe. For

although his printed works

give a good idea of his

competence, nevertheless in

order to judge his very great

skill one must hear him

playing impromptu, with

toccatas full of admirable

ingenuity and inventiveness.

Which is why he deserves to be

recommended for his

originality to all our

organists, to make them want

to come and hear him in Rome.’

Unlike Frescobaldi‘s works,

those of Louis Couperin were

not published during his

lifetime, nor indeed before

the twentieth century. They

have come down to us in the

form of manuscript copies. The

main source, the Bauyn

manuscript (Bibliothèque

Nationale de France, Paris),

is a veritable goldmine of

seventeenth-century

harpsichord music. Apart from

the pieces by Louis Couperin,

it also includes those written

by Jacques Champion de

Chambonnières, as well as a

varied collection of works by

French, English, Italian and

German composers, including

Frescobaldi and especially

Froberger. It provides us with

a ‘concentrate’ of the

masterpieces that were written

for the harpsichord during the

first half of the century.

Little is known about the life

of Louis Couperin, nor do we

know exactly when he composed

his works. Born at

Chaumes-en-Brie around 1626,

he was one of the eight

children of Charles Couperin,

who was an organist, tailor

and wine-grower. The Couperin

children of his generation

must have gained their early

musical training within the

family, in much the same way

as the Bachs in Thuringen.

Louis played the viol, the

organ and the harpsichord

(such versatility was common

at that time). In his Parnasse

françois of 1732, Evrard

Titon du Tillet reports a

story, probably dating from

around 1650: ‘The three

brothers [Louis, François and

Charles Couperin], with some

friends, also musicians,

decided on Chambonnières‘ name

day to go to his château [also

in Brie] to serenade him.’ The

master of the house, then at

the height of his fame, was

agreeably surprised by the fine

pieces that were presented,

and on learning that the

compositions were by Louis,

immediately presented his

compliments. Chambonnières

‘displayed great kindness to

him and told him that a man

like himself was not made to

stay in the provinces, and

that he absolutely must come

with him to Paris. This

Couperin accepted with

pleasure. Chambonnières

presented him in Paris and at

court, where he was

appreciated.’ Despite the fact

that Titon du Tillet was born

more than twenty-five years

after the events he relates,

it is likely that there is

some truth in his story.

Otherwise, we know that

Couperin was appointed

organist of the church of St

Gervais in Paris in 1653 and

that the king created a post

of treble viol player for him.

He died in Paris in 1661, at

the age of thirty-five.

Frescobaldi‘s successive

revisions of his works lead us

to believe that the ordering

of the pieces and their

content were exactly as the

composer wished them to be.

The same cannot be said of the

various manuscript sources of

the works of Louis Couperin.

The Bauyn manuscript presents

his harpsichord works in two

parts. The first part consists

of fourteen preludes, arranged

by key. It shows one of the

musician's most original

features, for these preludes,

like those of the lutenists

and theorbists of the time,

present only the pitch of the

notes on the stave with no

indication of duration or

measure. It is up to the

player to create the rhythm of

the piece, to improvise while

respecting the musical

framework provided by the

composer.

The second part contains

various dance movements,

classified according to key. It

is therefore possible,

although Couperin himself

makes no mention of the fact,

to group pieces together to

form coherent Suites,

in the manner of lute suites

or of the entrées

(groups of dances, unified by

subject) in the ballets de

cour. Couperin used the

fashionable dance movements of

the time (allemande, courante,

sarabande, gigue, chaconne or

passacaille), sometimes adding

choreographic forms inherited

from the previous generation

(volte, gaillarde, branle de

basque or canarie). Thus he

remained faithful to the

firmly established French

tradition, whereby ‘in the

order of things there are two

degrees (Philosophy and Dance)

that are capable of raising

man to his perfection’. He

also left an extraordinary Pavane

which, being the only piece in

F sharp minor, cannot be

included in a suite and

therefore stands alone.

Mersenne described this dance

as being of such gravity that

it could ‘even be danced with

cloak and sword’.

Setting aside the

chronological comparison, what

do Girolamo Frescobaldi and

Louis Couperin have in common?

To begin with, although their

means of expression were

different, they were both

masters of counterpoint.

Although Frescobaldi

cultivated the art of

imitation, stemming from the

polyphonic compositions of the

sixteenth century and

generating fugal forms, he

shared with the younger

musician the creation of a

style that was perfectly

adapted to the keyboard, in

the most digital sense of the

term. The two artists thus

join the Netherlands composer

Sweelinck and the Englishman

Bull, two great

representatives of the same

school.

The influence of writing for

plucked string instruments is

another common feature. In

Frescobaldi‘s case, it

resulted partly from his

probable association with

Alessandro Piccinini, a

lutenist who worked for the

Este court at Ferrara, and his

more certain relations with

Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger,

‘il Tedesco della Tiorba’, who

was also in the service of

Francesco Barberini. The same

arpeggiated style is found in

Louis Couperin's Préludes,

and in many of his dance

movements. And our

harpsichordist was a friend of

the amateur lutenist Charles

Fleury, also known as

Blancrocher, for whom he

composed a Tombeau

following his accidental death

in 1652.

Finally, the German

harpsichordist Johann Jakob

Froberger also provides an

invisible link between the two

composers. From 1637 to 1641

he studied with Frescobaldi in

Rome, where he was also

regularly in touch with

Athanasius Kircher during the

elaboration of his Musurgia

Universalis, one of the

most influential of all music

treatises, comparable to

Mersenne‘s Harmonie

Universelle. Froberger

almost certainly met Louis

Couperin during his stay in

Paris in 1652, a fact

supported by three

indications; the composition

of a Tombeau fait à Paris

sur la mart de Monsieur

Blancheroche,

accompanied by a commentary in

which Froberger states that he

was an ‘excellent friend’ of

Blancrocher; Louis Couperin's

composition of a Prélude à

l'imitation de Mr Froberger

(title found in the Parville

manuscript in the library at

Berkeley); finally, the

presence in the Bauyn

manuscript, a corpus

displaying great homogeneity

of style, of many pieces by

Froberger, alongside those of

Chambonnières and Louis

Couperin.

More deeply, Frescobaldi and

Couperin also shared the same

perception of the musical

discourse in the early years

of the seventeenth century.

Their treatment of

instrumental music was similar

to that of vocal music of the

time, aiming to achieve the

best possible expression of

the affections of the soul,

the object of music being ‘to

please, and to arouse in us

various passions’. In those

days when the theories of

celestial mechanism were being

popularised, with their

implications of a new

positioning of man in an

infinite universe, thinkers

and creators applied

themselves to solve the

mystery of the relationship

between the impulses of the

soul and their physical

manifestations. In a talk

given in 1668, the painter

Charles Le Brun presented his

view of that mechanical

relationship: ‘Passion is an

impulse of the soul, which

depends on the sensitivity,

and which arises either in

compliance with what the soul

believes to be good for it or

as a means of escaping from

what the soul believes to be

bad for it; and usually

everything that causes passion

in the soul causes the body to

react in some way.’ Thus, he

summarised ideas that had been

developed earlier by Mersenne

in his Harmonie

Universelle of 1636.

Baroque art of the first half

of the seventeenth century was

full of movement and

efferyescence. Even in the

apparent simplicity of an

austere Still life with

wafers, we perceive a

world in which everything is

possible, everything is

imaginable. Blaise Pascal who,

more than any other, knew how

to bring out the tragic

contradictions of this world,

noted in his Pensées:

‘Our nature lies in movement;

absolute repose is death.’ In

the virtuosic passages of a toccata

or the bewitching rhythm of a

chaconne, the Baroque

musician is saying just that.

Jean-Paul

Combet

Translation:

Mary Pardoe

|

|

|

|