|

|

1 CD -

073 - (c) 2005

|

|

| Clavierorganum |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| William BYRD (c.1542-1623) |

Pavan

(16a)

|

|

5' 15" |

1 |

|

Galliard

(16b)

|

|

1' 31" |

2

|

|

Clarifica me,

Pater (49)

|

|

2' 58" |

3

|

|

Qui Passe (19)

|

|

3' 51" |

4 |

|

Alman (89)

|

|

1' 42" |

5

|

|

Pavan (14a)

|

|

5' 21" |

6

|

|

Galliard

(14b)

|

|

1' 35" |

7 |

|

La

Volta (91)

|

|

1' 18" |

8 |

|

Pavan

(23a) |

|

5'

29"

|

9 |

|

Galliad

(23b)

|

|

1' 41" |

10 |

|

Ut

re mi fa sol la (64)

|

|

7'

32"

|

11 |

|

Ground

(43)

|

|

3' 13" |

12 |

|

Rowland

(7)

|

|

2' 46" |

13 |

|

Fantasia

(13)

|

|

7' 54" |

14 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Gustav LEONHARDT |

|

Clavecin de Malcom

Rose, d'après Lodewijk Theewes (1579)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Chapelle de l'hôpital

Notre-Dame de Bon Secours, Paris

(Francia) - novembre 2004

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Alpha |

|

|

Recording Engineer

/ Editing

|

|

Hugues Deschaux |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

nessuna |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Alpha - ut

pictura musica | 073 |

1 CD - durata 52' 12" | (c) 2004 |

DDD |

|

|

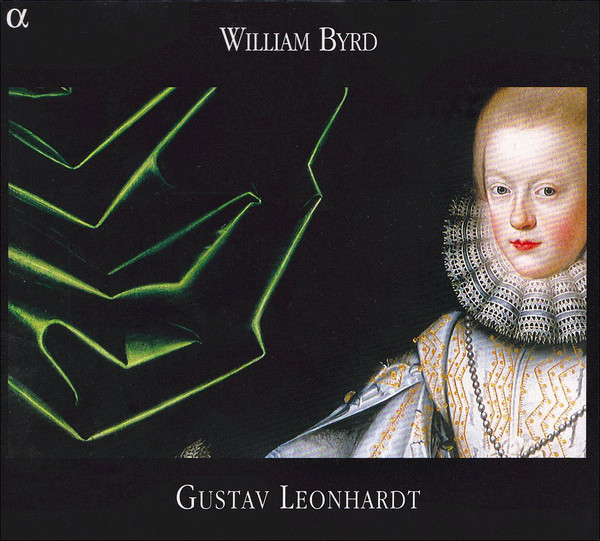

Cover Art

|

|

William Larkin,

Lady Diana Cecil, countess of

Oxford, Greenwich, Londres,

Ranger's House, Suffolk Collection |

|

|

Note |

|

Digipack

|

|

|

|

|

William

Larkin (London,

c.1585-1619)

Lady

Diana Cecil, countess of

Oxford, c.1614-1618 (Oil on

canvas, 200 x 117 cm)

Greenwich

(London), Ranger's House,

Suffolk Collection

By the end of

the reign of the monarch

affectionately dubbed “Good

Queen Bess” by her subjects,

who died in 1603, costume had

reached a level of elaboration

and sophistication never

before seen in England, or

even in Europe. This

development was the

consequence of the attitude of

majestic dignity in which this

last Tudor queen draped

herself, at once close and

aloof, and of the devotion in

which she was held by subjects

grateful to her for having

established peace and

consolidated the institution

of monarchy without the

shedding of blood. They had

sacralised Elizabeth, a

“Virgin Queen” reputed intact

- or so at least she loudly

proclaimed, making this

condition a token of her

exclusive fidelity to her

people. Thus she had become

almost a new Virgin Mary, in a

sense setting herself up in

place of the original demoted

by the Protestant religion.

The portraits of this daughter

of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn

had become ventable icons,

immobile, hieratic, cosmic and

harmonious representations, at

once of the mystic body of

royalty and of the sovereign's

presence, real and symbolic.

The royal portrait became a

votive image that was to be

the object of a

quasi-religious cult, whose

object, moreover, was also

head of the new Anglican

Church. In order to ensure the

diffusion of these images to

the four corners of the realm,

and throughout the known

world, models were created

that could be reproduced as

desired, with iconographic

adaptations stressing such and

such an aspect of the royal

person. While not invested

with the same legitimacy, her

courtiers and their ladies

were to imitate the queen, and

thus be transformed into

“saints” fixed “for all

eternity”.

Following on from these

developments, early Stuart

culture under James VI and I

(1605-25) represents a period

of transition that perpetuates

the demanding aesthetic canon

of Elizabethan erat Hence it

is not surprising that the

Jacobean portrait has an

old-fashioned, archaic quality

which in its turn cultivates

idealisation rather than

mimesis, whereas, during the

reign of Charles I (1625-49),

a new style was gradually to

instil in the last vestiges of

the English Renaissance a

resurgence of nature over a

background of Venetian

picturality, characteristic of

the European Baroque.

Diana Cecil (1596-1654) was a

member of the Exeter branch of

the illustrious line of Cecil

(Cissell), whose origins date

back to the tenth century and

to which William Cecil,

Elizabeth's principal

counsellor and lord treasurer,

also belonged. Her first

marriage was to the hereditary

grand chamberlain Henry de

Vere, eighteenth Earl of

Oxford (and son of William

Byrd's patron), whose family

came originally from the

Cotentin region of Norrnandy;

she brought him a dowry of £

30,000. She later married

Thomas Bruce, Earl of Elgin. A

notable beauty, Diana had a

twin sister, Anne, Countess of

Stamford, who like her was the

subject of a life-size,

full-length portrait by

William Larkin. The son of an

obscure London innkeeper, this

painter is supposed to have

been a pupil of Nicholas

Hilliard (c.1547-1619) whose

career straddles the two

reigns. Larkin represents the

final phase of the

'neo-medieval' style so

greatly appreciated by his

aristocratic clientele, and

shows a taste for the

brilliant colour of his

masters miniatures. The

twinship of these effìgies in

this pair known as the

“Suffolk set”, the artist's

masterpiece, is total: except

for the discreet identifying

label placed at the top of the

two pictures and a different

decoration of the bottom of

the hanging to the right, the

blonde hair, fair complexion

and shorter stature of Anne

constitute the only difference

compared with the brown hair

and darker colouring of the

Countess of Oxford. In

accordance with the formula

developed by the artist, the

subject stands before a wall

hung with a double curtain of

rich “Bronzino“ green, with

its stiff folds, ridges

transformed into arabesques

gleaming with vibrant light:

the trick has earned Larkin

the nickname of “curtain

master”. As usual, one arm is

leaning on the back of an

armchair in a paler shade of

the same colour, its legs

reminiscent of old curule

chairs, on which rests a

cushion with golden tassels;

the same gold braid fringes

the seat and emphasises the

chair's outlines in decorative

bands. The face with its

direct gaze (the arch of the

eyebrows carefully drawn), the

make-up and the vermillion of

the lips are set off by the

long pearls that sparkle at

her earlobes. Silver-coloured

as was the Elizabethan norm,

Diana's dress is decorated

with a multitude of slashed

folds and embroidered with

gold. Her bosom, decked with a

long row of pearls knotted at

the centre on an appliqué in

the form of a white rose,

fixed to the tight corsage,

has disappeared under the

hodice. The inverted pyramid

placed on top of that formed

by the farthingale (a Spanish

import), whose summit

coincides with her waist, is

faithful to the fashion of

earlier days. The lace ruff,

typical of the early

seventeenth century, is echoed

by elegant cuffs of the same

material. The right hand,

whose wrist is adorned with a

bracelet, holds a fan, another

borrowing from Spain, while

the left clutches an elegant

embroidered handkerchief,

doubtless scented, which the

lady can drop in the hope that

a gallant will take it as a

pretext to court her, despite

the string that attaches it to

her arm. To the right, the

hanging with its gilded

decoration echoes the

sumptuous Turkish carpet laid

on the floor. The horror

vacui that is the

consequence of such

accumulation of ornament

indicates that the artist is

more preoccupied with beauty,

meticulous detail, technical

precision and refinement, than

with spatial values, which

places his art in the late

Mannerist tradition of his

country.

A decade after the great

queen's death, the English

portrait, following on

directly from those of the

sixteenth century, is as

formal as can be, and in this

respect entirely in conformity

with the tradition established

under Elizabeth. If the linear

and symmetrical, bilateral

character of the composition

creates an impression of

structural rigour, reinforced

by the many straight lines,

the effect is nonetheless not

static, for the satiny surface

is animated by frequent

disruptions. While the

steadiness of the subject's

gaze and the almost mechanical

insertion of the barely turned

head in the ruff heighten this

impression, the waves created

by the angularities of the

curtain offer a “contrapuntal”

animation that attenuates the

apparent rigidity. The

complexity of these numerous

angles and interlacing lines

brings to mind the music of

the composer, who requires

skill and vinuosity of his

performers. England is at the

dawn of a new age; while still

remaining faithful to its

heritage, unique for its

insularity and early break

with Rome, the country's art

retains intact its curiosity

for can be seen and heard on

the continent, and resolves

the tensions resulting from

this contact with 'terra

firma' by retaining only what

seems suitable, and

reinterpreting that as it

pleases. Though more inclined

towards music and poetry,

England is nevertheless

beginning little by little to

appropriate the art of

painting that was initially

left in the hands of the

Germans, the Flemish and the

Dutch, while still taking

advantage of their presence.

In 1658 - twenty years after

William Larkin - Anton van

Dyck, a pupil and competitor

of Rubens, will paint the

portrait of Diana Cecil now

conserved in the Prado: by

then, the Renaissance will

have had its day, and a new

century will have begun.

Denis

Grenier

Department

of History

Laval

University, Quebec

Translation:

Charles Johnston

Byrd -

Harpsichord pieces

The genius of

William Byrd flowered at a very

special period in the history

of Western music, the last

years of the sixteenth century

and the first decades of the

seventeenth. Those composers

active at the time lived

through the historic moment

that marked the end of the

Renaissance and the first

stirrings of the Baroque: a

period of unique upheavals, as

the voice became emancipated

from its harmonic

accompaniment, and independent

instrumental music began to

develop. Byrd was to be at

once a witness and an

architect of this profound

transformation.

A pioneer of these modern

times, acknowledged as one of

the founding fathers of

keyboard music in Europe, he

was to encourage the

blossoming of the new

generation, that of the early

Baroque, active in the first

half of the new century. And

what a generation! Dominated

by the towering figure of

Monteverdi, Shakespeare's

contemporary, it could also

boast, in the Catholic

territories of southern and

western Europe, the Frenchman

Jehan Titelouze, the Ferrarese

Girolamo Frescobaldi, organist

at St Peter's in Rome, and the

Andalusian Francisco Correa de

Arauxo; while in the

Protestant lands to the north

and east there were the

Dutchman Jan Pieterszoon

Sweelinck, organist in

Amsterdam, the Englishmen John

Bull and Orlando Gibbons, and

the Saxon Samuel Scheidt. It

was indeed a most fortunate

era, for to these famous names

we might add those, important

though less well-known, of the

Neapolitan Giovanni Maria

Trabaci, the Walloon Pieter

Cornet, and the Thuringian

Michael Praetorius.

With the passing of the

centuries, Byrd has come to be

seen as the foremost composer

of his time, marking the

apotheosis of English music.

After the new peak attained by

Purcell at the end of the

seventeenth century, the

inspiration of this school was

gradually to dry up, leaving

pre-eminence to Italy, then to

France and Germany. Byrd's

heyday precisely coincided

with the reign of Queen

Elizabeth I. She came to the

throne on the death of Mary

Tudor, in 1558; Byrd was then

not yet twenty. And her long

reign ended forty-five years

later, in 1605. Byrd was thus

the Elizabethan composer par

excellence, occupying the same

role as his younger

contemporary Shakespeare

played in the domains of drama

and literature.

Though he spent his whole life

in the service of the Anglican

Church, Byrd was born a Roman

Catholic, and a Catholic he

remained. The Act of Supremacy

enacted by Henry VIII in 1534

asserted the independence of

the English national Church, a

dissident Catholic Church.

Byrd was still a child when

Edward VI, son of Henry VIII

(and of Jane Seymour),

confirmed the independence of

the Church of England: the

Book of Common Prayer

established the Anglican

liturgy, while the influence

of Reformation ideas

increased. But on Edward's

death, his half-sister Mary

Tudor, daughter of Catherine

of Aragon and short-lived

second wife of Philip II of

Spain, returned to

Catholicism. Her violent

repression of the Protestants

earned her the unenviable

nickname 'Bloody Mary'. Then

came another volteface when

she died in 1558, to be

succeeded by another

half-sister, Elizabeth

(daughter of Anne Boleyn), who

was no sooner on the throne

than she instituted a vigorous

anti-papist reaction. With the

Oath of Supremacy and Act of

Uniformity of 1559, followed

by the promulgation of the

Thirty-Nine Articles of 1563,

she laid the foundations of

the Anglican Church. Amid the

unrest of this troubled

period, Byrd upheld the faith

of his fathers. His prestige

must have been considerable,

given that the queen continued

to protect him and that he was

never harassed during the keen

religious disputes that shook

the country.

We know little of the

childhood of William Byrd. He

is thought to have been born

to a musical family in London

around 1540. There is good

reason to believe that he sang

from an early age as a boy

chorister in the Chapel Royal,

where he probably studied the

organ and composition under

its director Thomas Tallis,

with whom he was later to

collaborate. He was certainly

a highly gifted child and

young man, for many of his

compositions date from his

teenage years. Gifted enough,

in any case, to be appointed

Organist and Master of the

Choristers at Lincoln

Cathedral in 1563, when he

must have been barely into his

twenties, with his

professional qualities

recognised by a salary

considerably higher than was

customary. He stayed at

Lincoln until 1570. Byrd very

quickly established himself as

an outstanding personality,

thanks to his performing skill

on keyboard instruments, his

burgeoning reputation as a

composer, and what one can

only term his charisma with

both colleagues and pupils.

Though few copies now survive,

Byrd had already composed a

great deal by this time, first

trying his hand at every genre

in imitation of the English,

Italian or Flemish masters,

and fairly rapidly finding a

language of his own.

In 1570 he appeared in London,

where he was reunited with his

friend Thomas Tallis at the

Chapel Royal, becoming the

latter's deputy. A close and

exemplary friendship grew up

between the two men. Byrd's

reputation was constantly on

the increase. Soon he was

fêted by a number of

high-ranking aristocrats,

achieving universal admiration

and the protection of the

queen in person, since in 1572

he was sworn in as a Gentleman

of the Chapel Royal. The next

year, the Earl of Oxford, a

poet- and himself a Catholic,

like most of the noble amateur

musicians Byrd frequented -

gave him a lease on land

belonging to him.

Five years after Byrd's

arrival at the Chapel Royal,

in 1575, the queen granted

Tallis and Byrd a monopoly on

music printing in England, a

line of business little

exploited until then. In order

to express their gratitude to

the sovereign, the two

composers dedicated their

first publication to her,

issuing in that same year a

collection of thirty-four Cantiones

sacrae, quae ab argumento

sacrae vacantur, Latin

motets for five to eight

voices, with each of them

contributing half the total.

The queen was then in the

seventeenth year of her reign,

and each man thus offered her

seventeen cantiones.

But alongside these motets,

Byrd did not neglect secular

instrumental music, and his

pavans and galliards for

virginal also date from this

period.

He was now at the height of

his activity as a composer.

Over the years, he published

four volumes of sacred music

in Latin, three masses and

three collections of sacred

music in English, not to

mention what was printed here

and there in collective

anthologies such as Parthenia.

Another sign of the popularity

of his works is that they were

often copied into manuscript

collections of music, in

particular the Fitzwilliam

Virginal Book and Will

Forster's Virginal Book.

The most important source for

his keyboard works is My

Ladye Nevells Booke, a

compilation finished in 1591.

Of all the dates that

punctuate the biography of a

figure who had by this time

become illustrious, one

especially deseryes mention

here for its signal importance

in the history of English

music: the year1613. This was

the date of publication in

London of an anthology of

works for virginal named Parthenia,

to which Byrd contributed

eight pieces. The plates of

this collection were entirely

engraved by William Hole; it

was the first time that music

had been printed by copper

engraving in England. At a

period when music was becoming

more complex and ornate, this

system was much more legible

than Gutenberg's movable type.

Moreover, it was also, at the

dawn of this century which was

to see the flowering of the

Baroque aesthetic, the very

first published collection of

instrumental music, and was to

remain so for decades to come.

Its very title proclaims the

fact loud and clear:

Parthenia, or The

Maydenheas of the First

Musicke that ever was

Printed for the Virginalls.

Thanks to his great renown,

Byrd attracted a large number

of talented pupils, so many

indeed that he was nicknamed

“The Father of Musick”.

Several are still celebrated

today, among them Orlando

Gibbons, Thomas Tomkins,

Thomas Morley, and John Bull.

Byrd gave up his post at the

Chapel Royal in 1618, on the

grounds of his advanced age,

and was succeeded by Gibbons

and Edmund Hopper. Like his

friend Tallis, he died in his

eighties, at Stondon Massey

(Essex), on 4 July 1623.

Byrd's oeuvre is extensive and

protean. His name is attached

to the “English virginalist

school”, which covers the

whole second half of the

sixteenth century and the

first half of the seventeenth,

and of which he is the most

illustrious representative, if

not indeed the founding

father. But the art of Byrd

cannot be reduced to this role

alone, however important it

may have been. His

compositional output is

divided between the sacred and

secular spheres - he wrote for

both church and chamber. Hence

it contains motets and psalms

on the one hand, and madrigals

with consort of viols on the

other. As to his works for

keyboard, these are intended

in part for virginals, in part

for organ, while also being

suitable for performance on

the lute. It should be

recalled here that the general

term “virginal” at that time

did not designate merely the

rectangular English spinet,

but the whole range of

keyboard instruments, as is

shown by an abundant

iconography.

A large corpus of some 130

pieces for keyboard by Byrd

has come down to us, varying

in length from one to ten

minutes. With the exception of

a few scattered pieces of a

whimsical variety, they

chiefly illustrate a small

number of genres which at the

time were at the height of

their popularity in England.

One may obserye in them Byrd's

twin penchant for both cyclic

works, unified and closed, and

open, expansive forms in

multiple sections.

This is a new, nascent art. As

a man of the late Renaissance,

Byrd conceived music from the

perspective of polyphony

organised into rich

counterpoint, whether in the

genres cultivated in the

sixteenth century, chiefly

motets and masses, or in the

new styles of music for

keyboard, even in the dances.

Again and again his

instrumental music seems to be

underpinned by the idea of

vocal polyphony. Yet he is

also a “modern”, with his solo

songs and his madrigals. These

diverse facets of his musical

personality are admirably

combined in the genre of

variations for keyboard. Here

he emerges as an eminent

master of elaboration over an

ostinato, whose various linked

episodes lead towards the

control of large-scale form.

These works are generally made

up of juxtaposed sections.

This is the case with the

fantasias or preludes. A

characteristic example is the

Fantasia in A minor, which

comprises three main sections.

Opening after the manner of a

ricercare, it becomes

increasingly animated, showing

a verve teeming with new

ideas, in a multitude of

rhythmic figures that jostle

with one another, binary or

ternary, sometimes lopsided,

reserving countless surprises.

Some such works seem more

particularly intended for the

organ, such as Clarifica

me, Pater, a youthful

work from the Lincoln period,

his first truly personal

piece.

Many of these pieces are

derived from dance steps.

Among them are the pavans,

followed by their galliards, a

genre that flourished all

through the Renaissance

period. The allemande, very

different in character, with

its top line richly charged

with ornamentation, was

becoming extremely popular at

this period. As to the volta

(called volte in

French), a triple-time dance

of Provençal origin, somewhat

slower than the galliard, it

had been much appreciated in

France since the reign of

Henri II. This was the only

dance that was performed in

couples, giving it an

audacious character further

emphasised by the leaping

three-quarter turns executed

by the dancers. Everyone knows

the famous painting showing

the Earl of Leicester dancing

this step with Queen

Elizabeth, whom he grasps as

she springs, as if in a

snapshot, without her feet

touching the ground.

But Byrd, as we have said,

shows a pronounced penchant

for the art of variation,

which sets in relief the

virtuosity of the performer

and even more so the

composer's imagination,

rhythmic invention and taste

for subtle, unexpected

harmonies. Especially when the

variations are founded on the

reiteration of a single

underlying motif, in the

“ground”, the English

equivalent of the chaconne or

passacaglia (as in Qui

Passe for my Lady Nevell).

This was to be the genre of

choice for musicians for more

than a century to come. For

here we have the affirmation

of the ideal of Baroque art:

to attain large-scale, unified

form by drawing the multiple

from the single, to display

unity in diversity. Or, as

Leibniz was to express it in

theoretical terms: “Perfection

is the harmony of things...

identity in variety.”

Gilles

Cantagrel

Translation: Charles

Johnston

|

|

|

|