|

|

1 CD -

118 - (c) 2007

|

|

Weltliche

Kantaten

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

BACH (1685-1750) |

"Angenehmes

Wiederau, freue dich in deinen Auen!",

BWV 30a |

|

38' 15" |

|

|

-

Coro: "Angenehmes Wiederau" |

4' 35" |

|

1

|

|

- Recitativo (SATB): "So ziehen

wir"

|

0' 56" |

|

2

|

|

-

Aria (Basso): "Willkommen im Heil,

willkommen in Freuden"

|

4' 27" |

|

3 |

|

-

Recitativo: "Da heute dir, gepriesner

Hennicke"

|

0' 38" |

|

4

|

|

-

Aria (Alto): "Was die Seele kann ergötzen"

|

5' 13" |

|

5

|

|

-

Recitativo: "Und wie ich jederzeit

bedacht" |

0' 40" |

|

6 |

|

-

Aria (Basso): "Ich will dich halten"

|

6' 38" |

|

7 |

|

-

Recitativo: "Und obwohl sonst der

Unbestand" |

0' 56" |

|

8 |

|

-

Aria (Soprano): "Eilt, ihr Stunden, wie

ihr wollt" |

4' 18" |

|

9 |

|

-

Recitativo: "So recht! ihr seid mir werte

Gäste" |

0' 49" |

|

10 |

|

-

Aria (Tenore): "So, wie ich die Tropfen

zolle" |

2' 53" |

|

11 |

|

-

Recitativo: "Drum, angenehmes Wiederau"

|

1' 05" |

|

12 |

|

-

Coro: "Angenehmes Wiederau" |

4' 58" |

|

13 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian BACH |

"Vereinigte

Zwietracht der wechselnden Saiten",

BWV 207 |

|

34' 33" |

|

|

-

Coro: "Vereinigte Zwietracht der

wechselnden Saiten" |

5' 05" |

|

14 |

|

-

Recitativo: "Wen treibt ein edler Trieb zu

dem" |

1' 54" |

|

15 |

|

-

Aria (Tenore): "Zieht euren Fuß nur nicht

zurücke" |

4' 19" |

|

16 |

|

-

Recitativo: "Dem nur allein Soll meine

Wohnung offen sein" |

2' 00" |

|

17 |

|

-

Aria (Duetto: Basso. Soprano): "Den soll

mein Lorbeer schützend decken" |

4' 53" |

|

18 |

|

-

Ritornello |

1' 45" |

|

19 |

|

-

Recitativo: "Es ist kein leeres Wort" |

1' 35" |

|

20 |

|

-

Aria (Alto): "Ätzet dieses Angedenken" |

5' 31" |

|

21 |

|

-

Recitativo: "Ihr Schläfrigen, herbei!" |

3' 05" |

|

22 |

|

-

Coro: "Kortte lebe, Kortte blühe!" |

4' 18" |

|

23 |

|

|

|

|

|

Monika Frimmer,

soprano

|

Les Chantres du

Centre de Musique Baroque du

Versailles | Olivier Schneebeli,

direction |

|

| Robin Blaze, alto |

Sophie Landy, Bèatrice

Gobin, Sarah Szlakmann, sopranos

|

|

| Markus Schäfer,

ténor |

Bruno Le Levreur,

Julien Freymuth, Arnaud Raffarin, altos |

|

| Stephan MacLeod,

basse |

Romain Champion,

Benoît Porcherot, Dominique Bonnetain,

ténors |

|

|

Arnaud Richard, David

Witczak, Louis-Pierre Patron, basses |

|

|

|

|

|

Café Zimmermann

| Gustav Leonhardt, direction

| Pablo Valetti, Konzertmeister |

|

|

Pablo Valetti, violon

& Konzertmeister |

|

|

Nicholas Robinson,

Mauro Lopes, Cecile Mille, David

Plantier, Pedro Martin Gandiati, violons |

|

|

Patricia Gagnon, José

Manuel Navarro, altos |

|

|

Petr Skalka, Etienne

Mangot, violoncelles |

|

|

Ludek Brany, contrebasse |

|

|

Céline Frisch, clavecin |

|

|

Emmanuel Alemany, René

Maze, Guy Ferber, trompettes

naturelles sans trous |

|

|

Diana Baroni, Sarah

Van Cornewal, traverso |

|

|

Patrick Beaugiraud,

Henru Michel, Clémentine Humeau, hautbois |

|

|

Laurent Le Chenadec, basson |

|

|

David Vateville, timbales |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Abbaye de

Saint-Michel en Thiérache, Aisne

(Francia) - maggio 2007

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Direction artistic |

|

Aline Blondiau |

|

|

Recording Engineer

/ Editing

|

|

Hugues Deschaux |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

nessuna |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Alpha - ut

pictura musica | 118 |

1 CD - durata 72' 47" | (c) 2007 |

DDD |

|

|

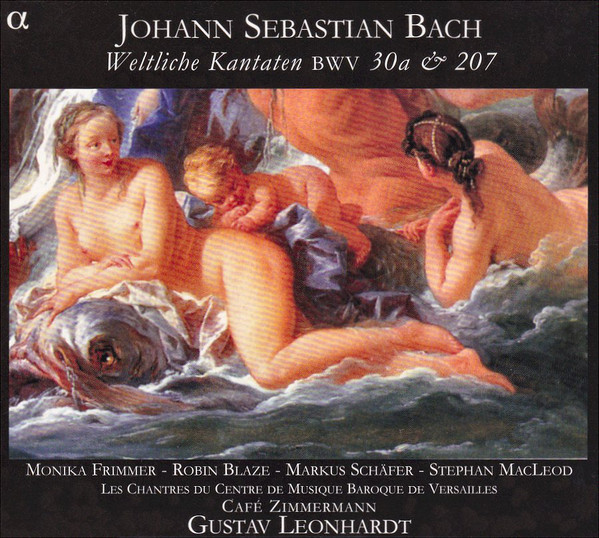

Cover Art

|

|

François Boucher,

The Triumph [The Birth] of Venus,

Stockholm, National Museum |

|

|

Note |

|

Digipack

|

|

|

|

|

François

Boucher (Paris,

1703-1770)

The

Triumph [The Birth] of

Venus, 1740 (Oil on

canvas, 130 x 162 cm)

Stockholm,

National Museum

Voluptuous

pleasure is the sum total

of Boucher's ideal: it is

the only soul his painting

possesses. Ask no more of

him than mythical nudes;

yet what sleight of hand,

what freshness of

imagination in that very

indecency, what harmony of

arrangement, to cast

pretty bodies onto

clouds... What a display

of blooming flesh, of

undulating lines, of forms

that seem to have been

modelled by a caress!...

The Venus whom Boucher

dreams of and paints is

only the physical Venus;

but how perfectly he knows

her! How skilled he is in

giving her all the

temptations of the

abandoned gesture, the

ready smile, the inviting

posture! How good he is at

placing her in an arousing

setting! And how

beautifully, in this

light, volatile, and

constantly reborn fidure,

he embodies Desire and

Pleasure!

The

Goncourt Brothers

Born of

sea-foam fertilised by the

blood of Uranus, then washed

up on the shore by the waves,

the goddess of love sits

languidly enthroned on a reef,

in her Isle of Beauty caressed

by the waters whence she

extends her empire. Venus is

accompanied by cheerful

Nereids whose suggestive poses

are enhanced by their

curvaceous bosoms and the

sinuous lines of their

magnificent posteriors.

Delighted by the advances of

the tritons, they are only too

pleased to surrender to their

seducers, dazzled by their

bronzed, tanned flesh tints and

the savage power of these

bodies set off by imposing

muscles. Multiplying their

feats of acrobatics, these

sea-gods enjoy the complicity

of 'carrier' dolphins while

cupids pirouette in the gentle

spray; the group is joined by

a few amorous doves, birds

sacred to Aphrodite. Above the

scene, head-over-hee1s, putti

roll themselves in luxurious

swirling drapery (a throwback

to Antiquity, by way of its

modern imitator Raphael),

whilst a male deity takes

pleasure in pouring the

contents of an immense conch

into the eddying waters. Freed

from all care, the festivities

take place in an atmosphere of

lasciviousness, with even the

raging clouds and the towering

rocky spurs apparently

manifesting their approval for

rejoicings which seem destined

to last eternally. Far from

casting a shadow over the

prevailing ambience, the thick

black clouds surmounting the

grotto which opens to the

right set in relief the happy

nonchalance of the protagonist

and the voluptuous pleasure of

their exchanges, suggesting

that a natural alcove away

from prying eyes is at their

disposal for intimate

love-play.

Acquired by Count Carl Gustav

Tessin, ambassador

extraordinary and future prime

minister to the king of

Sweden, an assiduous client of

the artist and devotee of

French culture, Boucher's

masterpiece takes its place in

a long tradition which made

eroticism, under cover of joie

de vivre, a recurring theme of

European painting. At the

moment when this topos

re-emerged with unprecedent

vitality and liberty of tone,

exalted by lightness of

tecnique, the painter handles

with brio a subject inspired

both by mythology and by the

youthful charm of his wife,

née Marie-Jeanne Buseau,

sometime copyst to the master

and, it was whispered, the

Swede's former mistress.

Colin,

prompted by frolicsome love,

Was

observing at his leisure,

one day,

The legs,

whiter than alabaster,

Of his

beloved Rose.

Now he

attended to the left,

Now the

right enticed him away.

"I don't

know", he said, "which of

the two to gaze on;

Their equal

beauties jostle for

attention."

"Ah!" says

Rose to him, "My dear,

without further ado,

You can

settle their quarrel by

placing yourself between the

two."

Alexis

Piron, Les Belles jambes

(1730)

On much the same wavelenght as

Piron, the poet and dramatist

from Dijon, this specialist in

female curves and fine legs

caresses nacreous skin with

his sensual and lively brush.

A ribald turn of mind might

imagine that the suggestive

seashell being emptied of its

content evokes the act of

love, and might even see in

the movement of the long

drapery towards the fissure in

the rocks a saucy allusion to

the type of intercourse to

which it is liable to play

host. The atmosphere of

Rocaille tends towards gaiety,

and we venture to suggest that

its common ground with the

secular music of Johann

Sebastian Bach, who can hardly

be accused of having

cultivated boredom, but

appears on the contrary to

have been something of a bon

vivant, might justify the

juxtaposition of the two. An

allegory reflecting the tastes

of the time, to be sure; an

effervescent and infectious

sense of elation, without a

doubt. Are the grace and

elegance, the verve of Boucher

(who died twenty years after

the composer), so highly

thought of in his clay, really

so alien to the idiom of the

Saxon when, inspired by the

commission in hand, his mood

grows festive?

Denis

Grenier

Department

of History

Laval

University, Quebec

September 2007

Translation:

Charles Johnston

Johann

Sebastian Bach - Two

secular cantatas

Like every

musician of his time, Bach

composed occasional music. At

Mühlhausen and again when he

was employed at the ducal

court in Weimar, he produced

wedding cantatas for the

daughters of wealthy citizens,

as well as serenades and music

for the celebration of the New

Year and other special

occasions. Some of them

required only modest forces,

while others - important civic

occasions, for example - were

much more sumptuous affairs.

Especially in Leipzig...

'Cantor zu St. Thomae et

Director Musices Lipsiensis'

was Bach's official title in

Leipzig, and he was

particularly attached to the

latter part, Director

Musices, Civic Director

of Music, a public

appointment. It meant that he

was not only responsible for

the music of the four

principal Leipzig churches and

for training the children of

the Thomasschule, the boarding

school attached to St

Thomas's. He was also called

upon for other aspects of the

city's musical life, which

meant facing an audience,

seeking approval, and

providing secular works -

cantatas, concertos or

orchestral suites - for

various civic entertainments.

There was great demand for new

music both at court and in the

city. Families and friends

would get together in their

homes to sing and play music.

There was music at school, in

church, and even in the

streets. Any event served as a

good excuse for music making,

and music provided the

backdrop for every aspect of

social life.

The inhabitants of Leipzig

were particularly fond of

nocturnal celebrations,

torchlight processions, and

serenades. Anniversaries,

birthdays, commemorations,

tributes, and the visits of

important personalities: all

were occasions for splendid

concerts, the culmination of

which - the long-awaited

moment - was the performance

of a short musical drama

(which was sung but not

acted). Bach wrote and

'produced' at least sixty

secular cantatas, only fifteen

of which have survived

complete, and they are the

least known and most

infrequently played of all his

works.

On this recording we present

two secular cantatas neither

of which today seems to

interest either musicians, who

rarely perform them, or

musicologists, who prefer to

study the sacred works they

later became. For Bach

subsequently used the same

material for two church

cantatas, and those are the

versions that are generally

heard. It was common practice

at that time to adapt and

re-use earlier compositions

and it is quite easy to

understand why. A sacred

cantata, written for a

specific church festival or a

particular Sunday in the

liturgical year, could be

brought out again year after

year. A secular piece, on the

other hand, was ephemeral;

normally the occasion for

which it was written would not

recur, there would be no

opportunity for a repeat

performance. Since writing it

had taken much effort, why not

use all or part of it again,

especially if the work had

been well received? It could

be converted into a liturgical

piece, which meant changing

the text, the context and the

characters, or it could also

be used for another secular

occasion. Likewise, sacred

pieces could be recycled for

other sacred occasions. But

what was not possible, because

it was sacrilegious, was a

move in the other direction,

from sacred to secular.

Shortly before his arrival in

Leipzig, Bach had been

involved in a wrangle with

Leipzig University. He had

laid claim to the traditional

right of the Cantor of the

Thomaskirche to be responsible

for providing music for the

services held at the

University Church of St Paul

(the Paulinerkirche). But the

Rector and some of the

professors had caused his

request to be turned down. So

it is easy to understand why

Bach thereafter missed no

opportunity to compose

brilliant tributes to that

institution and to its staff,

some of whom, moreover, became

lifelong friends of his:

August Müller, for example,

who was Professor of

Philosophy, and Johann Abraham

Birnbaum, Professor of

Rhetoric. In 1726, still

smarting no doubt from the

rebuff, he was commissioned to

compose a congratulatory work

for the installation of Dr

Gottlieb Kortte of Frankfurt

University as Professor of

Jurisprudence at Leipzig.

Kortte, who was only

twenty-eight at that time,

died five years later.

A solemn official occasion of

that type called for

impressive musical forces.

Furthermore Bach wished to

create an impact. He composed

his cantata Vereinigte

Zwietracht der wechselnden

Saiten BWV 207 for four

soloists, a chorus of three

trumpets and timpani, two

flutes and three oboes, and a

string ensemble. The work was

performed on 11 December 1726,

most likely in one of the

university buildings, where

the three trumpets must have

sounded with brilliant effect.

Some of the musicians were

probably students, members of

the Collegium Musicum, then

directed by Schott, from whom

Bach was shortly to take over.

The cantata presents four

allegorical figures: Happiness

(soprano), Gratitude (alto),

Diligence (tenor) and Honour

(bass). The libretto was

probably written, as usual

during Bach's early years in

Leipzig, by Christian

Friedrich Henrici, better

known as Picander.

Congratulatory texts such as

this are often unfairly

criticised nowadays, accused

of being fulsome, unoriginal

and uninspired. But they were

only following the literary

and stylistic conventions of

their time, which included the

use of allegory. The

recitatives are noticeably

longer than those of church

cantatas; they are used to

expand on an element from the

poem and bring out its

multiple allusions, which must

have appealed to the audience

at such events. In the alto

recitative, No. 6 in the

score, for example, the

subject of law (Kortte, we

remember, was Professor of

Jurisprudence) is represented

by a reference to Astraea's

Temple, Astraea being the

goddess of justice who,

according to Ovid, chose to

abandon earth for heaven after

the fall of the Golden Age. At

the end of the same

recitative, the candles

metaphor is one that everybody

present would have understood,

referring simply to Professor

Kortte's students, enlightened

by his teaching.

The solemn but spectacular

introduction, using the full

forces, is an arrangement,

transposed and adapted, of the

third movement of the First

Brandenburg Concerto BWV 1046,

composed almost ten years

previously. The opening words

address the strings and the

timpani, and obtain a festive

response. In the middle of the

cantata, after the

aria-duetto, comes a purely

instrumental 'ritornello',

providing an interlude in the

laudatory proceedings; the

second trio is also borrowed

from BWV 1046. Preceded in

each case by a recitative, the

three arias, including the

aria-duetto for bass and

soprano, are performed by the

allegories; they are written

with refinement and subtlety.

Note in particular the

delicacy with which Diligence

makes the invitation to follow

his path. The four characters

share one last recitative

addressed to the new

Professor, then the work ends

with a splendid chorus.

Bach later used all the

material from this cantata as

it stands, with the excepnon

of three of the recitatives,

and of course with a new text,

for the cantata Auf,

schmetternde Töne der

muntern Trompeten BWV

207a, in celebration of the

name day of the elector of

Saxony, Augustus II, on 3

August 1735.

It is believed that there were

three or four special

non-religious occasions each

year in Leipzig, for which

Bach was expected to provide

celebratory music, in addition

to his task of writing for the

churches. Some eleven years

after his cantata for

Professor Kortte, he was

requested to write an

occasional piece in honour of

a man called Johann Christian

von Hennicke. Hennicke was a

senior civil servant, a

commoner who had been ennobled

in 1728 by the all-powerful

Count Heinrich von Brühl,

prime minister of Saxony under

Augustus III. Hennicke was

vain and unpopular, and he was

accused of corruption. In 1737

he became a minister in

Brühl's cabinet and a property

at Wiederau, near Leipzig,

became his fief, of which he

officially took possession on

28 September. Bach's secular

cantata, or rather dramma per

musica, Angenehmes

Wiederau, freue dich BWV

30a, was written to celebrate

that occasion.

The new lord of Wiederau, who

enjoyed the favour not only of

the prime minister but also of

the queen, was a perfect

example of what we today would

call a parvenu. But since he

was an important figure in

local politics, it was

necessary to comply with his

wishes. Picander as usual

produced the laudatory

libretto, its praise spoken

once again by four allegorical

figures: Time (soprano), Good

Fortune (alto), Fate (bass),

and the River Elster (tenor) -

the river that flows through

the estate at Wiederau. In

another homage cantata, Schleicht,

spielende Wellen BWV

206, written the previous

year, each of the four

soloists had represented a

river.

In this work the appropriately

festive orchestral forces are

almost the same as in BWV 207,

but more ample. The work is in

thirteen movements: the

opening grand chorus is

repeated to different words at

the end; between the two, five

arias are linked by six

recitatives. The work follows

the relatively conventional

structure of the poem in

homage to Hennicke. The first

four of the five arias are da

capo. Some of the

movements appear to have been

taken over from earlier works

(notably the choruses, Nos. 1

and 13, and the aria, No. 5).

In contrast with the rather

ordinary arrangement of the

movements, however, the music

is constantly delightful:

imaginative and pleasing to

the ear, often with a

dance-like quality (beginning

with the syncopations of the

first chorus), and very lively.

Ideal for pleasing both the

audience and the dedicatee!

Let us just point out the

passepied in the first aria

('Willkommen im Heil', No. 3)

and, after a long instrumental

introduction that is repeated

in conclusion, the second aria

('Was die Seele kann

ergötzen', No. 5), in which

Good Fortune sings in dialogue

with the flute and both are

supported by the muted first

violin with the other strings

playing pizzicato. The

vehement bass aria (No. 7) is

transported with enthusiasm,

and the trio in movement No. 9

- where Time sings 'Eilt, ihr

Stundenl' - is strikingly

beautiful.

Bach could not possibly have

left such exquisite music to

lie dormant. A few months

later, at a time when his

creative genius appears to

have temporarily dried up -

hardly any original new works

from the period 1734-39 have

come down to us - he re-used

most of the material from this

fine work for another cantata,

BWV 30, Freue dich, erlöste

Schar, in celebration of St

Michael's Day, 24 June 1738.

Although the latter is

performed more often, it was

important to present at last

the original secular version.

Gilles

Cantagrel

Translation: Mary

Pardoe

|

|

|

|