|

1 LP -

(p) 1963

CRM 508 Mono - CRS 1508 Stereo

|

|

Variations,

Toccatas, Fantasias

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Jan Pietersyoon

SWEELINCK (1562-1621) |

Fantasia

8 |

organo |

|

|

A1 |

|

Chorale

variations, "Ich ruf zu dir, Herr Jesu

Christ"

|

organo |

|

|

A2 |

|

Echo Fantasia 15 |

organo |

|

|

A3 |

|

Toccata

20 |

cembalo |

|

|

B1 |

|

Variations,

"Est-ce Mars"

|

cembalo |

|

|

B2 |

|

Toccata

23

|

cembalo |

|

|

B3 |

|

Variations,

"More Palatino"

|

cembalo |

|

|

B4 |

|

Variations,

"Von der Fortuna, werd' ich getrieben" |

cembalo |

|

|

B5 |

|

Paduana

Lachrimae |

cembalo |

|

|

B6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gustav

Leonhardt, organ (Larenskerk in Alkmaar)

& French harpsichord of the early

eighteenth century

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Larenskerk, Alkmaar

(Olanda) - 1962

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Direction artistic |

|

- |

|

|

Recording Engineer

|

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Cambridge Records |

CRM 508 Mono - CRS 1508 Stereo | 1

LP | (p) 1963 | ANA

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

- |

|

|

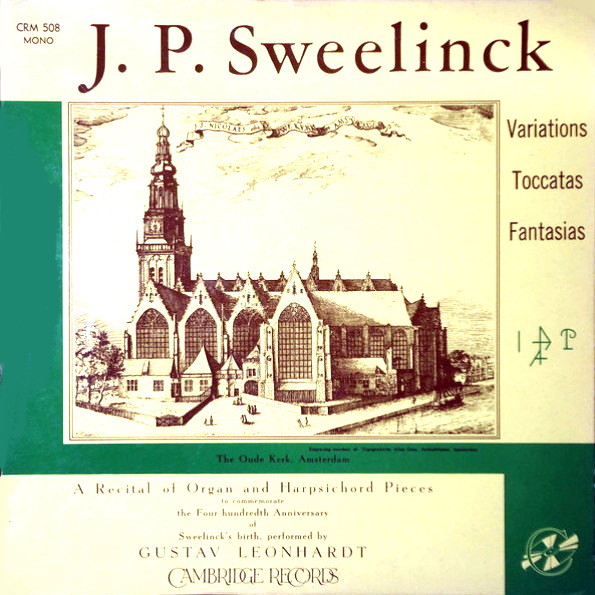

Cover

|

|

Oude Kerk, Amsterdam

|

|

|

Note |

|

A Recital of Organ

and Harpsichord pieces to

commemorate the Four-hundredth

Anniversary of Sweelinck's birth.

|

|

|

|

|

SWEELINCK

OF AMSTERDAM

Jan

Pieterszoon Sweelinck

(Zweling, Schweling),

rightly famous for his

choral music, was, above

all, a keyboard player and

composer of keyboard music.

He was also a distinguished

Amsterdammer during

the century when it was a

great European center of

art, architecture, science

and literature - described

by Vondel as the "Queen of

Europe". The zeal of the

lowlands, and especially

Amsterdam, for keyboard

music was perhaps rivalled

only by Elizabethan England

where the harpsichord was

becaming enormously popular,

and where its vogue was

enhanced by the music of

Sweelinck's contemporaries,

William Byrd, Giles Farnaby,

and JohnBull.

Prosperous Amsterdam in the

time of William of Orange

retained a serious regard

for music in spite of tastes

that had become puritanical

in other areas. In the Oude

Kerk, Sweelinck was retained

not by the Calvinistic

congregation, but by the Burgomeesters,

to play every day after

service in the evenings, as

well as on Sundays. The two

organs in the church were

the proporty, not of the

church, but of the City of

Amsterdam. Whether Sweelinck

remained a Roman Catholic,

or became an adherent of the

Reformed theology, is both

unknown and irrelevant. The

use of the organ in church

was fiercely argued during

the seventeenth century.

Even the venerable

Constantijn Huyghens

published a book not long

after Sweelinck's time

(while his son Dirck was

organist at the Oude Kerk)

called On the Use or

Non-use of Organs in

Churches of the United Low

Countries. He

concluded that it should be

permitted, if it were done

with discretion, and was

shortly answered by a

vigorous antidotum

published by another more

puritanical writer.

Sweelinck's concerts on the

organ of the Oude Kerk drew

such praise from admirers

that the poets Hooft and

Vondel both contributed

poems in his memory. His

contemporaries included the

poet Roemer Visscher, the

scientist Constantijn

Huyghens, and the builder of

both the Westerkerk and many

of Amsterdam's famous

towers, the architect

Hendrik de Keyser. Although

the distinguished group of

musicians poets and artists

which formed the "Circle of

Muiden" (so called after the

castle of Muiden in which

they frequently met) came

into formal existence only

after Sweelinck's death, he

was a guest of its owner,

Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft,

and later his son Dirck was

persuaded to join the circle

to play on the "klavesim" at

Muiden.

"Mr. Jan" also became famous

as the "organistenmaker" who

drew students (not the least

of whom was his own son) of

prodigious abilities, such

as Samuel Scheidt, from

Halle, and Jakob Praetorius,

from Hamburg. Others,

including Scheidemann, came

from as far away as Leipzig

and Danzig. Historians

delight to point out that

the tradition of composition

associated with Sweelinck

reaches from Scheidemann

through Reinken to none

other than J. S. Bach.

Sweelinck never journeyed

farther from North Holland

than Antwerp, and then only

for a few days. His own

student days were spent with

a local master, probably Jan

Willemsz Lossy. His

reputation was as great in

his own time as it is today,

and his native city gave due

honor to the "Orpheus of

Amsterdam", which it did not

always give his

contemporary, Rembrandt van

Riijn.

It is very likely that

Sweelinck was acquainted

with the Englishman John

Bull, who lived in Brussels

and Antwerp after 1617, and

was in the Lowlands as early

as 1601. Bull wrote a

Fantasia based on one of

Sweelinck's themes in the

year of his death, possibly

as a commemoratio. Another

English contemporary, the

lutenist John Dowland,

copied works of Sweelinck,

and perhaps met him during

his time as lutenist to the

Danish Court of Christian

IV. Such influences from

across the channel gave to

both English and Dutch

musicians a cosmopolitan

keyboard style, now related

to the lute, now to the

idiom of the keyboard. While

Sweelinck never journeyed to

Venice to study with Zarlino

(an error

perpetrated in Mattheson's Ehren-Pforte

of 1740), he did know the

latter's treatise, Istituzioni

Harmoniche. He is

known to have advised his

students to study it, but so

far, only rumor supports the

idea that he also made a

translation of it for them.

Sweelinck's trip to Antwerp

in 1604, his longest journey

from Amsterdam, had a

musical purpose which must

have pleased him, for he was

sent at the behest of the

city fathers to purchase a

harpsichord for the town.

Although Antwerp was

reluctantly ceding its

primacy as a port, because

of its shallow harbor, to

the diligent amsterdammers,

it could boast of a

superiority which doubtless

interested "Mr. Jan" much

more: he must certainly have

purchased an instrument from

the workshop of Hans

Ruckers, who with his sons

Johannes (Jean) and Andreas,

was the most famous

harpsichord maker in all of

Europe.

A fascinating speculation,

which could have influence

on the performance of

Sweelinck's keyboard music,

centers on the possibility

that he was also a player of

the lute. This arises not

only because of his possible

connection with Dowland and

other lutenists, but

especially because a curious

reference to a "Chyterboeck

by Mr. Sweelinck" (or

instruction book for lute or

guitar) occurs in several

booksellers' catalogs in and

around Amsterdam later in

the century. No copy of the

supposed work survives, but

the popularity of the lute

and related instruments in

Amsterdam was well known

(Huyghens, for instance, did

not neglect to take along

his lute when he went to

study in England), and the

freedom demanded in the

performance of Sweelinck's

keyboard music ("Mein junges

Leben" or the "Lachrimae"),

for instance, makes it seem

likely.

Sweelinck is a favorite with

historians because his music

initiates and illustrates

styles and techniques which

were to figure in keyboard

music well into the

eighteenth century. If his

student, Samuel Scheidt, can

be called the originator of

the organ chorale preludem

as much can be attributed to

Sweelinck himself because of

the influence his chorale

variations had on Scheidt.

In the Toccatas especially,

he formed a spectacular

bridge between the

ruminating, free Venetian

style, and that of later

northern composers such as

Froberger and even

Buxtehude. He took the

folksong variation to a

higher point of perfection

than his English

contemporaries, and his Echo

Fantasias represent a unique

achievement, perhaps rivaled

in choral music by the

Italians of St. Mark's but

never equalled in keyboard

music until the antiphonal

organ works of French

composers at the end of the

century.

SWEELINCK'S

INSTRUMENTS

The

keyboard instruments of

Sweelinck's day possess some

characteristic sounds which

have to do with the

integrity of expression in

his music. An awareness of

these is essential for any

modern performance; indeed,

the music sometimes stands

or falls on the point of

authenticity of sound. Of

the two organs used by

Sweelinck in the Oude Kerk,

nothing remains; the present

instrument there was built

in the early eighteenth

century. The most notable

difference between the north

European organs of

Sweelinck's time and those

of the late seventeenth and

early eighteenth centuries

can be observed in the Pedal

division, which was intended

in the earlier instruments

almost entirely for cantus

firmus lines or organ

points, for which it was

often coupled to another

division. The Pedal had very

few stops and was unsuited

to contrapuntal playing;

even the pedal keyboards

tended to be rudimentary and

less convenient than those

of Bach's day. The

disposition of th larger

organ in the Oude Kerk

follows:

Builders: Hendrik Niehoff

and Hans Suys, circa 1540,

altered 1567 (Sweelinck

became organist at the Oude

Kerk in 1581.)

HOOFDWERK

FF-a'

- Prestant 8

- Octaav 4 and 2

- Mixtuur

- Scherp

RUGWERK

- Prestant 8

- Octaav 4

- Mixtuur

- Scherp

- Quintadeen 8

- Roerfluit 8

- Roerfluit 4

- Baarpijč 8 (reed)

- Sifflet 1-1/3

- Kromhoorn 8

- Schalmey 4

- Tremulant

(F to a"; no F

sharp, no G sharp,

no g" sharp)

|

BOVENWERK

- Prestant 8

- Roerfluit 8

- Fluit (open) 4

- Nasard 2-2/3

- Gemshoorn 2

- Siffet 1-1/3 (or

1?)

- Tertschimbel

- Trompet 8

- Zinck 8

(CDE - a"; no g"

sharp)

PEDAAL

- Trompet 8

- Nachthoorn 2

(with coupler, to

Hoofdwerk, one

octave lower)

|

Mr. Leonhardt had used for

these recordings one of the

most splendid of the Dutch

early eighteenth century

organs, which is in the 15th

century Larenskerk in

Alkmaar. It is a large

instrument which Mr.

Leonhardt uses in the style

appropriate to the music,

avoiding heavy 16' pedal

sound and other effects

unlikely for Sweelinck. The

alkmaar instrument, restored

recently by D. A. Flentrop,

is almost entirely the work

of the Schnitger family in

1725. Its main case, which

dates from Sweelinck's time,

was designed by the

celebrated van Campen; the

Schnitgers retained some

pipes from the earlier

organ. The spacious

acoustics of the great

Gothic church contribute

much to the effect of this

instrument and the

reverberation that is heard

here is important for organ

music of this, or any other,

period.

The harpsichords available

to Sweelinck would habe been

of the Flemish sort (also

popular in England) such as

the one he was commissioned

ti purchase in Antwerp in

1604 for the city of

Amsterdam. Although it very

likely possessed two

keyboards, with an 8' and 4'

register on each of two

keyboards, they could not be

coupled in the manner of an

eighteenth century

instrument. So far as is

known now, it was only after

the time of the Ruckers

family that couplers came

into use, for the very good

reason that the keyboards

were at different pitches,

so that transposition was

possible. For these

recordings, Mr. Leonhardt

has used a French

harpsichord of the early

eighteenth century. In view

of the splendor of the sound

available, he has

occasionally employed a

Plenum consisting of 8', 8'

and 4' (using the coupler,

operated by sliding the topo

keyboard in and out),

although this effect was

impossible on Sweelinck's

instrument.

Beyond his obvious talent

for performance and

interpretation, Mr.

Leonhardt is remarkable for

his practical musicology.

Sweelinck lived and composed

long before the days of

equal temperament, and Mr.

Leonhardt has tuned the

harpsichord in mean-tone

tuning for this reason.

There are some surprises for

the twentieth century

listener. Major chords,

especially in final

cadences, have a dramatic

clarity and purity. Free of

the roughness of tempered

thirds, they incisively

punctuate the harmonic

outline.

Pitches altered to effect

this tuning are noticeable

in exposed passages, and are

disturbing, at first, to

some listeners. Some notes

sound "out of tune", but it

is just this difference

which brings them into pure

third relationship in

harmonies.

Within a hundred years of

Sweelinck's death, mean-tone

tuning succumbed to equal

temperament and the harmonic

complexities of first-rank

keyboard compositions.

Sebastian Bach's

"Well-Tempered Clavier" as a

monument is both cornerstone

and gravestone.

HARPSICHORD

OR ORGAN MUSIC?

In

1943, the Netherlands

Society for Music History

republished Sweelinck's

complete keyboard works

(Seiffert), attempting to

divide them into those

intended for the organ, the

harpsichord or both.

Although such a separation

of music from an age when

much music was written

simply for "Klavier",

leaving the choice of medium

to the performer, must

always be somewhat

arbitrary, much of

Sweelinck's music benefits

from performance on one

instrument rather than on

the other. It is just as

unlikely that the variations

on secular tunes, such as

"Est-ce Mars" of "Mein

junges Leben" were intended

for the organ, as it is

certain that the chorale

variations calling for Pedal

cantus firmus were not meant

for the harpsichord. The

Echo Fantasias were surely

only organ pieces and works

such as the Fantasia

Chromatica, with the

chromatic motif on which it

is constructed, played on a

reed stop in the Pedal, have

a special affinity for the

organ. Aside from this, some

of the pieces, especially

the Toccatas and certain of

the Fantasias, seem equally

appropriate to either

keyboard instrument. It is

true, also, that some of the

harpsichord pieces are

effective on the organ, even

though the figuration and

arpeggiated style point to

the harpsichord. In some

cases, it would have been

impossibible or, at best,

inconvenient to transfer

works to the organ, either

because of the difference in

keyboard range or because of

missing chromatic notes in

the extreme treble and bass

registers of organ

keyboards.

SIDE

ONE: ORGAN MUSIC

Fantasia

8 - Although the

Seiffert edition lists work

as for "organ or

harpsichord," its dominant

features suggest the organ.

One such characteristic is

the cantus firmus, which can

be extracted from the inner

voices or bass and put into

the Pedal, employing a reed,

as Mr. Leonhardt does in

this performance. The lenght

of the work and the obvious

divisions into large

sections (unlike some of the

more episodic Toccatas and

Fantasias) also suggest the

differing pitch levels and

sonorities associated with

different keyboard divisions

of a good-sezed organ. Rapid

scale passages and other

figurations, associated more

often with the harpsichord,

can also be satisfactorily

executed on the organ, with

proper voicing sensitive

action, and stops of high

pitches.

CHORALE VARIATIONS, "Ich

ruf zu dir, Herr Jesu

Christi" - There is no

doubt that Sweelinck's

Chorale Variations are

intended for performance on

the organ, preferably a

rather large one of three

Keyboards and pedal, the

latter to be used for cantus

firmus and organ points or

as the composer instructs.

In a work such as "Ebarm

dich mein". Sweelinck

specifies "Manualiter unndt

Pedaliter" for certain

variaions. In this

performance, Mr. Leonhardt

begins with the chorale tune

played on a Sesquialter

accompanied by flutes and

continues it on a reed stop

in the Pedal in the second

variation; keeping the

melody in the Pedal in the

thord variation (where it is

in the tenor), the work is

concluded with a Plenum

(stops of 8', 4', 2' pitch

plus a mixture).

ECHO FANTASIA 15 -

This Fantasia differs from

some of Sweelinck's more

frequently performed echo

pieces in that it has

unusually long echo phrases,

and, except for the

introductory section, very

little polyphonic writing.

Perhaps the most popular

genre of Sweelinck's organ

music, the Echo Fantasias

appeal because of their

straightforward simplicity

and because they fit the

organ so idiomatically. In

this performance the proper

effect is made possible

because of an authentically

reverberant acoustical

environment. The dependence

of such music on

reverberation is

important,since any

antiphonal work is in part a

"sound effects" piece; when

performed in a "dead"

building, much of its life

disappears. The almost

inevitable presence of three

to five seconds

reverberation in most

European churches is a

factor often overlooked in

judging the success of organ

music, not only of the

seventeenth century, but of

later music, as well.

SIDE

TWO: HARPSICHIORD MUSIC

Variations,

"Est-ce Mars" - Surely

intended for the harpsichord

rather than the organ, not

only because of the secular

nature of the text, but also

because of the batteries of

repeated notes and falling

cadential arpeggiations,

"Est-cd Mars" is among the

most attractive tunes set by

Sweelinck. That it was a

popular one can be seen from

the settings by the

Englishman Farnaby and by

Sweelinck's student, Samuel

Scheidt; but Sweelinck's

jollity surpasses all the

others with its humorous

play on the repeated notes

characteristic of the tune,

the infectious "walking

bass" and the incessant

rhythm generated by the

repetition of broken chords

outlining the harmony. Its

charm is heightened by

unexpected shifts of

tonality in the middle of

Variation 7 and the

never-failing device of

changing to triple meter in

Variation 6.

Giles Farnaby called his

setting of the same tune (in

the FITZWILLIAM VIRGINAL

BOOK, Part II) "The New

Sa-Hoo" and Nicolaes Vallet

set it for four lutes.

Later, Gervaert even worked

the same tune into a Belgian

national hymn. It is said to

have been sung in England

with a text beginning,

"Slaves to the world should

be toss'd in a blanket".

Despite its cosmopolitan

history, "Est-ce Mars"

probably originated in

France. Dpubtless, the poet

remembered that "The great

god Mars" was the lover of

Venus, as well as the God of

War:

"Est-ce

Mars le Grand Dieu des

Alarmes que je vois?

Si l'on

doit juger par ses

armesm je le crois.

Toutes

fois j'apprends en ses

regards,

Que c'est

plutot Amour que Mars."

TOCCATAS

20 and 23 - Not so

"French" as some of the

Toccatas of the slightly

later Froberger (see CRM

509, CRS 1509 for Mr.

Leonhardt's performance).

Sweelinck's Toccatas suggest

the fiery passage work and

cadential flourishes of

Frescobaldi, Froberger's

teacher. Another similarity

is the episodic form of

these pieces and the

rhythmic freedom which their

performance demands. It is

perhaps significant, in view

of other Italian influences

on Sweelinck, that the

Frescobaldi works were first

published during the

former's lifetime (1615).

Toccata 23 differs from

number 20 in that it does

not possess lenghty

polyphonic sections, but

depends even more on

idiomatic harpsichord

writing and the devopment

(again suggestive of

Frescobaldi) of short scalar

and rhythmic motifs.

VARIATIONS, "More

Palatino" - Popular in

the seventeenth century as a

German drinking song, "More

Palatino" has been recorded

in various students'

notebooks of the time. Since

many young Hollanders went

to Heidelberg to study, they

must have introduced the

tune and text to Amsterdam.

The tune was also set by

Buxtehude, and an as yet to

be identified setting exists

in the library at Luneburg.

For Sweelinck's setting,

there is only one source,

which is anonymous, but

unquestionably his, because

of its style which is

identical with that of other

variations on secular tunes.

"More

palatino bibimus, ne

gutta supersit

Unde suam

possit musca levare

sitim

Sic

bibimus, sic vivimus

In

academicis."

VARIATIONS,

"Von der Fortuna werd' ich

getrieben" - Another

indication of the

cross-influence between

Dutch and English keyboard

music of the sixteenth and

seventeenth centuries, "Von

der Fortuna" was known in

England as "The Hanging

Tune". Ie appears in the

FITWILLIAM VIRGINAL BOOK,

Part I, in a setting by

William Byrd: "Fortune, my

foe, why dost thou frown on

me?" It was also set by

Samuel Scheidt, who may have

learned it from Sweelinck,

his teacher, although he

identified it as an English

melody, "Cantilena Anglica

Fortunae". In the TABULATURA

NOVA of 1624, Scheidt

coupled Sweelinck's

variations with his own.

Sweelinck's treatment is

notable for its expressive

shifts from major to minor,

a device his pupil knowingly

appropriated in his own

variations.

PADUANA LACHRIMAE -

Yet another connection

between the Lowlands and

England appears in John

Dowland's lute song, "Flow,

my tears", which he arranged

for five strings of lute in

the LACHRIMAE, OR SEVEN

TEARES FIGURED IN SEVEN

PASSIONATE PAVANS (1905).

There are also variations on

this tune by Byrd and

Farnaby in the FITZWILLIAM

VIRGINAL BOOK, Part II. It

is the basis for Sweelinck's

Paduana, which he has marked

"Collorirt" - perhaps to

apply not only to

"coloratura" running

passages, but also to

lute-like arpeggiations and

his favored harmonic devices

of cross relations

(reminiscent of Byrd) and

changes from minor to major

tonalities. Again, Mr.

Leonhardt's performance,

because of its expressive

freedom, causes the listener

to wonder hopefully whether

Sweelinck might also have

been a lutenist as well as a

keyboard player!

John

Fesperman

|

|

|

|