|

1 LP -

(p) 1964

CRM 509 Mono - CRS 1509 Stereo

|

|

Organ and

Harpsichord Pieces

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Jakob

FROBERGER (1616-1667) |

Toccata

II |

organo |

|

3' 04" |

A1 |

|

Toccata

VI

|

organo |

|

5' 05" |

A2

|

|

Fantasia I |

organo |

|

7' 06" |

A3

|

|

Toccata

V

|

organo |

|

5' 21"

|

A4 |

|

Capriccio

I

|

organo |

|

5' 32"

|

A5 |

|

Toccata

XXI |

cembalo |

|

2' 15" |

B1 |

|

Tombeau

- Blanc rocher |

cembalo |

|

3' 53" |

B2 |

|

Suite

XVIII (G minor)

|

cembalo |

|

7' 15" |

B3 |

|

Toccata

VIII

|

cembalo |

|

2' 01" |

B4 |

|

Ricercare

X

|

cembalo |

|

2' 23" |

B5 |

|

Suite

XIX (C minor)

|

cembalo |

|

7' 44" |

B6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gustav

Leonhardt, organ (Michaelskerk in

Zwolle) & French harpsichord of the

early eighteenth century

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Michaelskerk, Zwolle

(Olanda) - estate 1962 - organo

Framingham, Massachusetts (USA) -

inizio 1962 - cembalo

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Direction artistic |

|

- |

|

|

Recording Engineer

|

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Cambridge Records |

CRM 509 Mono - CRS 1509 Stereo | 1

LP | (p) 1964 | ANA

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

- |

|

|

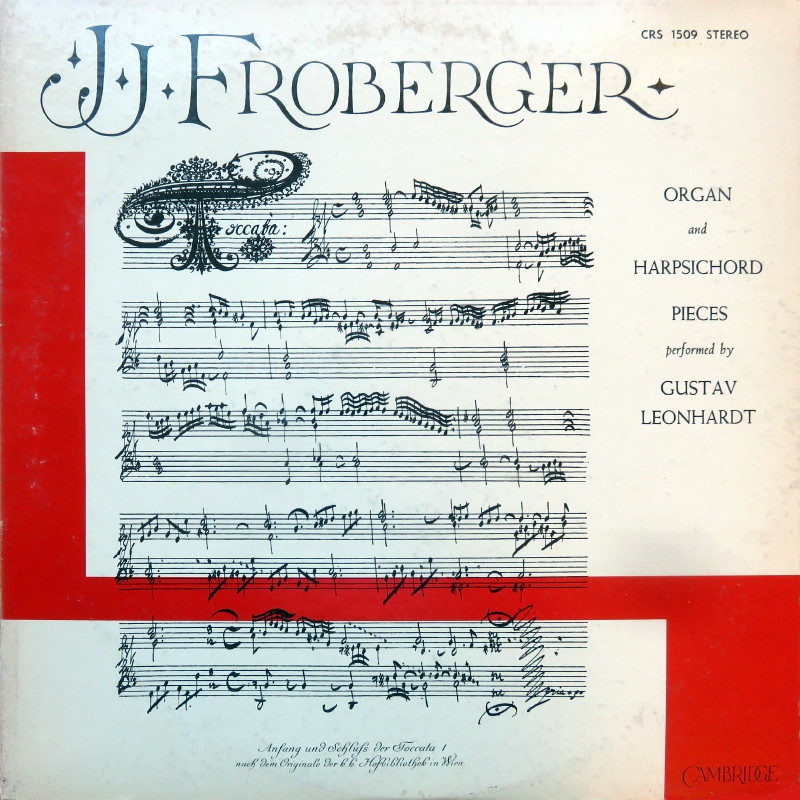

Cover

|

|

Prima pagina

autografa del Libro Secondo di

Toccate, Fantasie, Canzone,

Allemande, Courante, Sarabande,

Gigue et altre Partite.

Manoscritto, Vienna, 1649. Vienna.

Österreichische

Nationalbibliothek, Musiksammlung,

Mus.Hs.18706.

|

|

|

Note |

|

A Recital of Organ

and Harpsichord pieces to

commemorate the Four-hundredth

Anniversary of Sweelinck's birth.

|

|

|

|

|

Mysticism,

Romanticism, Eclecticism

Much

of the attraction which the

keyboard music of Johann

Jakob Froberger holds for

the modern listener arises

from certain exotic, even

mystical, qualities which

distinguish his music from

that of his contemporaries.

He relies rather more on

intuitive response than on

the established forms adn

conventions of the day, and

yet remains stylistically

very much a child of his

time. His music is best

approached with a minimum of

preconceptions and with some

understanding of 17-century

musical practices.

When Froberger writes in the

established polyphonic forms

of capriccio, canzona or

ricercare, the structure of

his music is readily

apparent. But even in these,

expressive qualities are

likely to be enhanced by

unexpected dissonance,

strange modulations and free

recitativo

excursions. In the freer

forms, he often breaks the

mold completely; with truly

wild bravura passages in a

toccata or painful

chromaticism and delicate

ornamentation in a lamento

or tombeau.

Finding subjective

self-expression so

pervasively present in music

written several decades

before the birth of J. S.

Bach may well surprise

toda's musical audiences.

Froberger was in fact a

Romantic. "Here is not a

tradition that expresses

itself, but a man and an

artist - a man who feels and

an artist who transmutes the

feeling. In its true

expression of a genuine

feeling, this composition is

as typically German - and,

for that matter, as

typically romantic - as a

Träumerei by Schumann, or an

Intermezzo by Brahms."

(Willi Apel in Masters

of the Keyboard,

discussing the Lamento

in memory of Ferdinand III.)

Besides the warmly personal

quality in much of

Froberger's keyboard music,

there are frequent

appropriations of Italian

and French mannerisms; here,

in the best sense, is a

truly eclectic composer. He

traveled widely, absorbing

the free keyboard style of

Frescobaldi (his teacher in

Rome) and, in Paris, the

attitude of his

contemporaries Louis

Couperin and Chambonnières

toward embellishments as a

means of expression as well

as decoration. Not content

merely to imitate, Froberger

created from these diverse

influences his own uniquely

powerful style. Even the

intricate mechanical

patterns of the English

Virginalists are echoed in

his variation pieces,

Manfred Bukofzer (in Music

in the Baroque Era)

speaks of Froberger's

"diversified elegance" and

"veritable inventory of

national styles", along with

the fusion of "the delicate

agrments of the French dance

music with the hold harmonic

language of the Italians".

Froberger was so immersed in

these different styles that

he even adopted their

notation: in the suites, the

two five-line staves normal

in France; in the toccatas,

two staves with six or more

lines each in the Italian

manner (a fragment of the

latter is reproduced on this

album). The traditional

canzona and fantasia were

written with one staff for

each voice, the usual

keyboard partitura.

Johann

Jakob Froberger

(1616-1667)

Froberger

was born in Stuttgart,

Germany, in 1616. By 1634,

he was in the service of

Emperor Ferdinand III in

Vienna, where he was

probably associated with the

music at the Hofkapel. From

1637 to 1641 on a stipend

from the court; he was in

Rome studying with

Frescobaldi, whose

chromatic, dissonant and

rhythmically free style he

prompty integrated into his

ows. He served as

Hoforganist in Vienna from

1641 to 1645; by 1650, in

company with Duke Leopold

(brother of Ferdinand III),

he was in Innsbruck and

Brussels where he met the

versatile Constantin

Huyghens. He arrived in

Paris sometime around 1652;

from 1653 to 1657, he was

back in Vienna and in 1662,

he made a trip to England.

This latter expedition

included an incident which

is reported as follows (in Grove's

Dictionary of Music and

Musicians): "In 1662

Froberger journeyed to

London, was twice robbed on

the way and arrived in so

destitute a condition that

he thankfully accepted the

post of organ-blower at

Westminster Abbey, offered

him by Christopher Gibbons,

then organist of the Chapel

Royal and the Abbey. Gibbons

was playing before the court

on the occasion of Charles

II's marriage, when

Froberger overblew the

bellows and thus interrupted

the performance; on which

the enraged organist

overhelmed him with abuse

and even blows. Froberger

seized the opportunity a few

minutes later to sit down to

the instrument and

improvised in a manner which

was at once recognized by a

foreign lady who had

formerly been his pupil and

knew his style. She

presented him to the king,

who received him graciously

and made him play on the

harpsichord to the

astonishment of all. This

curious anecdote is not

mentioned by English

writers, but is given by

Mattheson ("Ehrenpforte")

from Froberger's own

manuscript notes. Mattheson

states that he became a

Roman Catholic during his

visit to Rome, but it is

almost certain that he was

one already, when he entered

the empeor's service in

1637." (It is possible that

Froberger became a lutheran

again while in London, and

that he was dismissed from

the court because of it.)

Froberger was thought to be

the best German organist of

his day, and his travels to

Paris and London were not

primarily to study but to

perform. His renown in his

own time is attested to in

Walther's Musicalisches

Lexicon of 1732 which

devotes as much space to him

(half a column) as to J. S.

Bach. Mattheson's Grundlage

einer Ehrenpforte of

1740 further substantiates

his fame as a keyboard

virtuoso in an account of a

competition in Dresden with

the formidable Matthias

Weckmann, from which the

contestants departed "with

mutual respect".

Froberger spent his last

years in the service of the

Duchess Sybilla of

Württemberg, his last

student as well as

patroness, who was said to

have learned from him "note

for note" the proper

interpretation of his music.

She was made to promise,

shortly before his death in

1667, "not to give any of

his compositions to anyone,

because they would not know

how to perform them

properly, and would only

spoil them". Present-day

music lovers ean be grateful

that her vow did not prevent

the works from eventually

appearing, especially since

it probably applied to

Froberger's last, most

expressive pieces.

For this recording, Mr.

Leonhardt used the modern

edition of Froberger's music

(found in Denkmäler der

Tonkunst in Österreich)

wich is based on the

manuscripts in the Vienna

Library and the works

published in 1693 and 1696.

SIDE

A - Organ Pieces

Toccatas

II, V, VI. It is likely that

Froberger was in Rome when

these toccatas were composed

- the fierce recitativo

sections, dissonant

chromaticism and almost

rubato tempi are all

strongly Italian in style. Toccatas

V and VI testify to

Frescobaldi's influence in

their inspired improvisatory

passages, written-out

embellishments, unexpected

changes of tonality and,

especially the Lombard

rhythm (near the end of VI).

[Lombard rhythm (a device

described in

Frescobaldi's First Book

of Toccatas and Partitas)

may be either written out or

introduced at the player's

discretion. It consists of

shortening the first and

lengthening the second of

two step-wise eighth or

sixteenth notes.] Toccata

II differs from

Frescobaldi's toccatas in

that it contains a fugal

section.

Toccatas V and VI are

marked "Da sonarsi alla

Lecatione" (to be played

during the Elevation), thus

giving them a liturgical

function and clearly

defining the organ as the

proper instrument on which

to play them. Toccata

II is equally successful on

the harpsichord but, as is

often the case, is unmarked

by the composer as to

medium. Mr. Leonhardt plays

each of the four sections on

a contrasting division of

the organ.

The six sections of Fantasia

I sopra Ut, Re,

Mi, Fa, Sol, La, are

set off from each other by

changes in texture, rhythmic

motion or meter. These are

underlined by changes of

keyboard for each section,

beginning and ending with

the majestic sonority of the

main division of the organ.

Preceded by harmonies which

are perhaps more bland than

those of the toccatas; Fantasia

I ends with a more typical

chromaticism and a cadence

with a "modern" dominant 7th

chord in C, created by a

suspension from the

preceding chord based on

B-flat - hardly a

conventional progression! As

Mr. Leonhardt observes,

hexachord fantasias [pieces

based on groups of six

diatonic notes with the

half.step between the third

and fourth] were so numerous

that they became "the

backhome of musical

organization, especially for

keyboard, in the 16th and

17th centuries."

Capriccio VI could

well have been written after

Froberger's return from

England rather than during

his Italian days. It is

predominantly polyphonic,

thus differing from the

Italian style pieces,

relying for example on

inversion (after the initial

statement of the chromatic

subject and in the third

section). The four distinct

sections are indicated by

cadences with fermatas or

changes of meter. Each

section is played on a

different keyboard or with a

different intensity od

sound, beginning with the

Principal stops of the main

division and ending with the

full chorus of the Rückpositiv,

including a 16' reed stop.

SIDE

B - Harpsichord Pieces

Toccata

XXI is an excellent example

of Froberger's Italian

styls; the writen out tritts

and other ornaments (often

beginning on the principal

note), as well as the

flashing sclar decorations

and harmonic changes are all

reminiscent fo Frescobaldi.

Toccata VIII is

notably idiomatic for the

harpsichord with elaborate

figuration as well as

brilliant passage work,

against which a three-voice

chord is held. The piece

divides into three sections,

punctuated by cadences in A

major, B major and E major,

and a successful performance

requires the contrasts of

tempo judiciously employed

by Mr. Leonhardt. Leading by

way of chromatic and

dissonant polyphony to the

long note values, the work

ends with an abrupt and

astonishing cadence.

Perhaps the most remarkable

of all the pieces recorded

here is the Tombeau sur

la Mort de Monsieur

Blacrocher in memory

of the great French lutenist

Blancrocher, Louis Couperin

and Froberger were present

at the gathering (probably

during the year 1655) which

was tragically terminated

when Blancrocher fell down

the stairs to his death.

(The comparison between

Couperin's tombeau dedicated

to Blanrocher and

Froberger's is a fascinating

one.)

The terms tombeau, lamento

and plainte were sometimes

feed interchangeably and it

is not easy to attach a

distinctive meaning to each.

Tombeau is deined as "a

composition written in

memory of one deceased",

while lamento and plainte

mean simply "music of

elegiac, mournful

character". Froberger wrote

a marvelously expressive

lamento to his patron,

Ferdinand III, and, later,

one for Ferdinand IV which

is actually divided into

"scenes", with pictures to

go with each (as in earlier

similar lute pieces and the

Biblical "Rosary" Sonatas of

Heinrich Biber).

This Tombeau calls

to mind the spontaneous,

arpeggiated medium of the

lute. As an expression of

respect and grief, it is

especially poignant at the

end where a descending

scale, tumbling down to low

C, can be nothing other than

a suggestion of the tragic

accident of M. Blancrocher.

Mr. Leonhardt's performance,

with its rhythmic freedom

and sensitivity to the

excruciating and dissonant

harmonies is in accordance

with the composer's

instructions, "Lequel se

joue lentement a la

discrétion sans observer

aucune mesur." (slowly,

without rhythmic regularity,

according to the player's

inclination).

Suite XVIII (G minor)

and XIX (C minor). Froberger

seems to have been the first

composer to collect several

dance movements in sequence

for keyboard. Although his

manuscripts show the

movements in the order Allemande,

Gigue, Courante, Sarabande

- as recorded here - the

1693 edition presents them

"mis en meilleur ordre"

(arranged in more proper

sequence) with the gigue,

when present, at the end.

Other 17th-century

composers, such as Heinrich

Biber, sometimes ended

suites with the sarabande

but, by the time of François

Couperin and J. S. Bach, the

gigue was firmly established

as the final movement.

Froberger, then, seems to

have invented the keyboard

suite but not the order that

eventually became standard.

Both o these suites were

doubtless written during or

after Froberger's sojourn in

Paris, and they illustrate

the French influence of

ornamentation and

stylization of dance

movements. Therefore, Mr.

Leonhardt employs ornaments

in the French style.

Particularly "French" in

feeling are the Courantes

of both suites, for which

the player must interpolate

most of the ornaments. It is

useful to remember that

earlier collections of

dances were originally

intended for the lute and

that it was still a very

popular instrument.

Arpeggiations (especially in

the Allemande of

XVIII) and repeated notes

(as in the Sarabande

of XIX) suggests the idiom

of the lute.

Ricercar X. Of the

more traditional polyphonic

forms, the capriccio and the

canzona were likely to be

based on lively,

instrumental themes, with a

new one for each section of

the piece. The fantasia and

the ricercare showed a

clearer debt to earlier

choral music, using more

vocal material or hexachord

themes. Ricercare X

is based on such a vocal

idea, which is varied in

each of the four sections of

the work. Each section is

set off by a change in meter

or note values. Section I is

in common time, Section II

in triple meter, Section III

in cut time and the final

section doubles the note

values without changing

meter. Due to its

monothematic organization,

this Ricercare not

only suggests variation

form, but also resembles a

tightly organized fugue. It

is not a fugue in the

18-century sense, however,

since there are no

"episodes" or sections which

do not include the main

subject of the piece.

The

Instruments

During

his travels, Froberger had

the opportunity to play

organs and harpsicords of

various styles. Italian

organs, which he could

hardly have avoided during

his study with Frescobaldi

at St. Peter's in Rome, were

much milder in sound and

more limited in tone color

than northern instruments.

The organs Froberger knew in

Vienna were probably of the

northern type, capable of

more varied and aggressive

sound than those he saw in

Italy. The 17th-century

northern instruments

normally possessed a

complete Pedal division,

capable of carrying a

polyphonic line or a cantus

firmus, with two or three

independent manual choruses

of brilliant quality.

Italian instruments,

including those of the

Antegnati family, the

leading builders in

17th-century Italy,

possessed a single keyboard

with 12 to 18 stops of Flute

and Principal quality and

few if any reed stops.

Often, stops were divided

with separate controls for

bass and treble. There were

no independent Pedal stops

and the Pedal keyboard, if

there was one, was coupled

to the manual for organ

points or an occasional bass

note.

An unusual effect peculiar

to the Italian organs was

the “Registro voci humani"

which consisted of two 8'

Principal stops, one of

which was a bit flatter

("Fiffaro") than the other,

thus producing an undulation

thought to suggest the human

voice. The same effect can

be obtained by drawing a

unison stop slightly less

than its full distance, thus

reducing the amount of wind

available to the pipes

(beginning of Toccata

V.)

The organ used for these

performances is in the fine

15th-century Gothic

Michaelskerk in Zwolle,

Holland. Whether Froberger

thought of his organ works

in terms of the Italian or

northern instruments, or

both, is not easy to decide.

Considering the splendid

results produced by Mr.

Leonhardt, there can be no

doubt that Froberger's music

speaks authentically through

this instrument. Perhaps the

most monumental organ in all

of Europe, it was designed

by Arp Schnitger in 1718

and, with alterations and

enlargements by his son

Frans Caspar, was completed

in 1721. There are four

keyboards and Pedal with

each division separately

encased, in accordance with

the practice of the high

baroque. The reverbentíon

time of the Michaelskerk is

about 5 seconds when empty

due to the lame cubic volume

of the building and the hard

natural materials used in

its construction. Organ

sound, more than any other,

is dependent on

reverberation for optimmn

effect, a factor

unfortunately often

overlooked in modern

architectural design and

organ building. The

instrument was completely

restored (1953-1955) by the

well known Dutch organ

builder and student of

Schnitger instruments, D. A.

Flentrop.

The best harpsichords

available to Froberger would

have been either Italian or

Flemish. The Italian

instruments provided two

stops at 8' pitch on a

single manual. Their tone is

rather flute-like, not rich

in high harmonics, and loud

at the instant of attack but

quick to die away, due to

light construction and short

strings. As a result, rapid

figures are clear, brilliant

and declamatory, while

sustained chords sound

somewhat bland and fade

abruptly. The Flemish

instruments are musically

quite different, owing to

heavier bridges and longer

strings; the tone is

brighter and more complex,

and held notes sustain

longer. The prevalent single

manual types offered either

two stops at 8' pitch of

moderately contrasting

quality or an 8' and a 4'

(octave) stop. It is

probable that Froberger had

access to the earliest

expressive two manual

instruments which provided

8' and 4' stops on the lower

manual and another,

brighter, 8' stop on the

upper which could be used

solo or added to the lower

by coupling.

The instrument used for this

recording is an early

18th-century French one. It

is therefore a musical

descendant of the Flemish

type, with two manuals and

8', 8' and 4' stops. The

lower manual 8' register,

however, slightly resembles

an Italian 8' stop,

especially in the soprano

part of the compass.

John

Fesperman

TECHNICAL

NOTE

The

harpsichord portion of this

recital was recorded in

Framingham, Mass., U.S.A.,

in the summer of 1962, using

ribbon microphones and NAB

equalization. The organ

side, recorded in Holland

earlier the same year, was

made with condenser

microphones and CCIR

equalization, which has

purposely not been

compensated for in transfer.

It may therefore be

desirable to reduce the

treble for the organ and, on

some equipment, increase it

for the harpsichord.

|

|

|

|