|

|

2 LPs

- 27 0532 3 - (p) 1987

|

|

| 2 CDs -

CDS 7 47996 8 - (p) 1987 |

|

| 2 CDs -

7243 5 62337 2 0 - (c) 2004 |

|

CLAVIERÜBUNG -

ERSTER TEIL - 6 PARTITEN

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

BACH (1685-1750) |

Partita

No. 1 B-dur, BWV 825

|

|

12' 03" |

|

|

-

Praeludium |

1' 59" |

|

A1 |

|

-

Allemande |

2' 24" |

|

A2 |

|

-

Courante |

1' 24" |

|

A3 |

|

-

Sarabande |

2' 34" |

|

A4 |

|

-

Menuet I und II |

2' 19" |

|

A5 |

|

-

Gigue |

1' 33" |

|

A6 |

|

Partita

No. 2 c-moll, BWV 826 |

|

13' 56" |

|

|

-

Sinfonia (Grave-Adagio-Andante) |

4' 28" |

|

A7 |

|

-

Allemande

|

2' 56" |

|

A8 |

|

-

Courante |

1' 18" |

|

A9 |

|

- Sarabande

|

1' 53" |

|

A10 |

|

-

Rondeau

|

1' 26" |

|

A11 |

|

-

Capriccio

|

1' 55" |

|

A12 |

|

Partita

No. 4 D-dur, BWV 828 |

|

20' 19" |

|

|

-

Ouverture |

4' 52" |

|

B1 |

|

-

Allemande |

5' 51" |

|

B2 |

|

-

Courante |

1' 55" |

|

B3 |

|

-

Sarabande |

3' 10" |

|

B4 |

|

-

Aria |

1' 23" |

|

B5 |

|

-

Menuet |

0' 59" |

|

B6 |

|

-

Gigue |

2' 09" |

|

B7 |

|

Partita

No. 3 a-moll, BWV 827 |

|

13' 26" |

|

|

-

Fantasia |

3' 04" |

|

C1 |

|

-

Allemande |

2' 03" |

|

C3 |

|

-

Courante |

1' 39" |

|

C3 |

|

-

Sarabande |

2' 24" |

|

C4 |

|

-

Burlesca |

1' 11" |

|

C5 |

|

-

Scherzo |

0' 50" |

|

C6 |

|

-

Gigue |

2' 15" |

|

C7 |

|

Partita No. 5

G-dur, BWV 829 |

|

13' 28" |

|

|

-

Praeambulum

|

2' 31" |

|

C8 |

|

-

Allemande |

3' 06" |

|

C9 |

|

-

Courante |

1' 00" |

|

C10 |

|

-

Sarabande |

2' 20" |

|

C11 |

|

-

Tempo di Minuetto |

1' 12" |

|

C12 |

|

-

Passepied |

1' 08" |

|

C13 |

|

-

Gigue |

2' 11" |

|

C14 |

|

Partita No. 6

e-moll, BWV 830 |

|

19' 54" |

|

|

-

Toccata |

6' 35" |

|

D1 |

|

-

Allemande |

2' 18" |

|

D2 |

|

-

Courante |

2' 32" |

|

D3 |

|

-

Air |

3' 06" |

|

D4 |

|

-

Sarabande |

0' 55" |

|

D5 |

|

-

Tempo di Gavotta |

1' 07" |

|

D6 |

|

-

Gigue |

3' 21" |

|

D7 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Gustav Leonhardt,

Hapsichord (William Dowd, Paris 1964,

after Michael Mietke, Berlin) |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Doopsgezinde Gemeente

Kerk, Haarlem (The Netherlands):

- 13 Febbraio 1986 (BWV 825-827)

- 2 aprile 1986 (BWB 828-830)

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Gerd Berg

|

|

|

Balance Engineer |

|

Hartwig Paulsen

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

EMI Records

"Reflexe" | LC 0233 | 27 0532 3

| 2 LPs - durata 46' 18" - 46'

48" | (p) 1987 | DIGITAL

|

|

|

Edizioni CD |

|

EMI Electrola | LC

0542 | CDS 7 47996 8 | 2 CDs -

durata 40' 36" - 54' 36" | (c)

1987 | DDD

Virgin "Veritas" | LC 7873 | 7243

5 62337 2 0 | 2 Cds - durata 40'

38" - 54' 38" | (c) 2003 | DDD

|

|

|

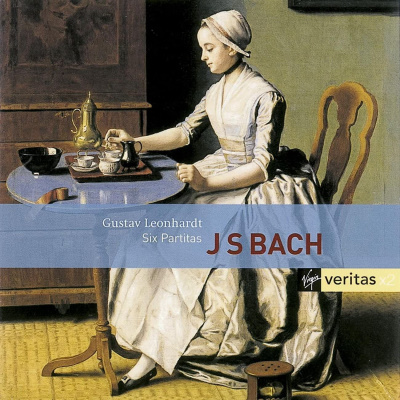

Cover Art

|

|

"Clavicimbel"

(Johann Christoph d. J. Weigel)

- Archiv für Kunst und

Geschichte, Berlin |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Clavier-Übung

1. Teil

To

his contemporaries, Bach was

famous as a virtuoso without

equal on the organ and other

keyboard instruments, not as

the composer of cantatas and

passion oratorios. There

were periods in his career,

even during the years when

he held the office of

Thomaskantor in Leipzig,

when he concentrated his

compositional energies

exclusively on his own

instruments. In keyboard

works he relied wholly on

himself, and so long as he

performed them himself they

could bot be misrepresented

by the failings of others. A

caesura divides his creative

output as early as the last

years as Hofkapellmeister in

Köthen, when orchestral and

chamber music gave way to

keyboard works, and the

‘English’ and ‘French’

suites were rapidly followed

by The Well-tempered

Clavier and the

inventions and sinfonias.

Our impression of Bach as

the master of counterpoint

has led us to look on The

Well-tempered Clavier

as his most important work

of that period, and to think

less of the suites. We do

not know what his own

opinion was. When, a few

years later, in Leipzig, he

published keyboard music for

the first time, he did not

choose strict contrapuntal

works, but the formally

freer partitas. No doubt

that was in part a

concession to these the

taste of the times, but it

was certainly not a

reflection on their relative

artistic merit. They are

superior to the suites, and

for quality of craftmanship

they are the equal of the

great fugal works: what they

yield to them in

contrapuntal skills they

make up in richness of

invention and rhythmic life

and vigour.

His first biographer, Johann

Nikolaus Forkel, relates

what Bach’s sons and pupils

told about the partitas’

reception: ‘The work when

new created a mighty stir in

the musical world. No one

had ever heard or seen

keyboard compositions of

such excellence. Anyone who

learned to deliver a good

performance of some of those

pieces, could make his way

in the world with them; and

in our own age a young

artist can still make his

name with them, they are so

luminous, euphonious,

expressive and ever new.’

That was written in 1802,

but the words are still true

today.

Bach took his time over

their publication. They

first appeared separately,

spread out between 1726 and

1731. The last was issued

simultaneously with the

first edition of all six

together, as opus 1: a

declaration of an intention

to publish more of his work.

The Clavier-Übung is

an interesting example of

the state of music printing

at that date. ‘Letter

press’, with movable type,

was still used for printing

partbooks but it was not

suitable for the polyphonic

complexity of keyboard

music, and engraving was not

yet practicable. Bach’s

score was therefore etched,

acid being used to bite the

music-text in mirror-image

on to a copper plate, from

which an intaglio impression

was taken. To assist this

process, Bach provided a

fair copy, obviously on one

side of the paper only,

which was then oiled to make

it transparent, so that the

notation could be traced

directly on to the plate. To

that extent, at least, the

first printing represents

something of Bach’s lost

autographs.

The original title-page of

opus 1 reads: ‘Clavir Ubung,

consisting of preludes,

allemandes, courantes,

sarabandes, gigues, minuets

and other galanteries;

composed for the spiritual

delectation of music-lovers

by Johann Sebastian Bach,

capellmeister to the court

of Saxe-Weisenfels and

directore chori musici

Lipsiensis. opus 1.

Published by the author.

1731.’

The somewhat didactic

denomination ‘Clavierübung’

- ‘keyboard exercises’ - alludes

to the two volumes with the

same title published forty

years earlier by Johann

Kuhnau, Bach‘s predecessor

as Thomaskantor. In Bach’s

case, the work consisted of

six partitas; the reason why

this is not stated on the

title-page probably has to

do with the retention of the

form of words used on the

six original separate

title-pages; but another

reason may very well have

been the thought that a list

of dance movements would

appeal to a wider public.

In this instance ‘partita’

is a rather elevated term

for ‘suite’: a series of

dance movements welded into

a whole by unity of key and

an intelligent sequence of

movements of different

rhythms, tempos and moods.

The backbone of the suite

was four dance movements

with different national

associations: the German

‘allemande’, the French

‘courante’, the Spanish

‘sarabande’ and the English

(more precisely Irish or

Scottish) ‘gigue’. These had

developed in various ways

during the 17th century: the

allemande had a faster and a

slower, adagio-like, form;

the courante had a variant

in a lively 6/8, which was

usually called a ‘corrente’,

while the slower courante

alternated between 3/2 and

6/4. Stylization at the

French court had made wholly

distinct types of these

dances, but in the hands of

Bach the types became

characters. Every one of the

six allemandes, courantes

and sarabandes is

individually formed, and

nothing is repeated. Each

dance is a musical character

piece, adopting and

underlining particular

traits of the original

model. Notice how, for

example, in the sarabande of

the fourth partita, the

customary accentuation of

the second beat in the bar

is used to shape an

eloquent, interrogative

intonation.

In addition to the four

basic movements, each

partita includes one or more

other movements conforming

to newer fashions, the

‘galanteries’ of the

tltle-page: minuets,

gavottes, bourées and so on.

They usually come after, or

on either side of, the

sarabande. They also stand

up well as separate pieces.

While the two minuets of the

first partita give the

impression that they would

be a welcome relief to

anyone who found the rest

too much for them, the

others are particularly

demanding to play and call

for meticulous rhythmic

control.

All the partitas open with a

movement in a free form,

different in each case. The

first has a vigorous

prelude, the second a

three-part sinfonia, the

third a fantasia for two

voices, the fourth a French

overture, the fifth a

concerto-like ‘praeambulum’,

the sixth a toccata. Taken

as a group, these six

movements amount to a

compendium of those free

forms of instrumental music

that did not originate in

dance forms.

We do not know why the

original publication of

these works was spread out

over five years. The third

and sixth partitas were

already completed by 1725.

Bach wrote them for the

‘Klavierbüchlein’ of his

wife Anna Magdalena. Some of

the material came from

earlier works: the Corrente

and the Gavotte of the sixth

partita were originally

composed for an earlier

version of the sonata for

harpsichord and violin BWV

1019a, and it is quite

possible that something of

other, earlier, lost works

survives in various

movements. Even if the

majority of the movements

were written shortly before

publication, the tonal

sequence of the set of

partitas must nevertheless

have been planned from the

ouset: there is nothing

random or accidental about

it. Beginning at B flat, it

proceeds by taking single

steps alternately up and

down the scale: B flat, C,

A, D, G, E, with major and

minor held in balance. From

an advertisement

accompanying the appearance

of the fifth partita, it

seems that there should have

been a seventh - which would

logically have been in F. In

the end Bach settled for the

half-dozen customary at the

time - but the first piece

in Part II of the Clavier-Übung,

published in 1735, the

Italian Concerto, is in F

major, and that is certainly

not by chance.

Georg

von Dadelsen

Translation

by Mary Whittall

|

|

|

|