|

|

1 LP -

20 20348-2 - (p) 1971

|

|

| 1 CD -

82876 70000 2 - (c) 2005 |

|

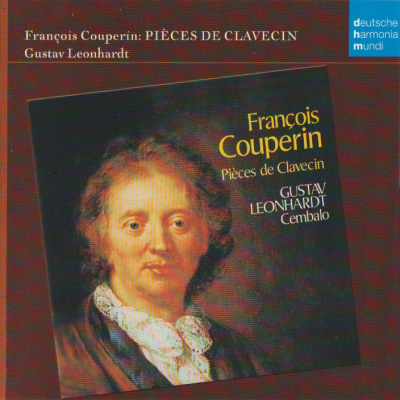

PIÈCES DE

CLAVECIN

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Frabçois COUPERIN (1668-1733) |

Prélude Nr. 3 in g - aus "L'art

de toucher le clavecin", 1716 |

|

|

1' 01" |

A1 |

|

Septiême Ordre - aus "Pièces

de clavecin" II, 1717

|

|

|

11' 43" |

|

|

-

La Ménetou. Rondeau

|

|

2' 38" |

|

A2 |

|

- Les Petits Ages

(La Muse Naissante | L'Enfantine |

L'Adolescnte. Rondeau | Les

Délices. Rondeau)

|

|

10' 42" |

|

A3

|

|

|

a) La Muse

Naissante |

2' 01" |

|

|

|

|

|

b) L'Enfantine |

1' 28" |

|

|

|

|

|

c) L'Adolescnte.

Rondeau |

3' 43" |

|

|

|

|

|

d) Les Délices.

Rondeau) |

3' 30" |

|

|

|

|

-

La Basque

|

|

2' 40" |

|

A4 |

|

- Les Amusemens

|

|

3' 59" |

|

A5 |

|

Prélude Nr. 5 in a - aus "L'art

de toucher le clavecin", 1716 |

|

|

2' 43" |

B1 |

|

Cinquiême Ordre - aus

"Pièces de clavecin" I, 1713 |

|

|

20' 49" |

|

|

- Allemande. La Logivière |

|

4' 58" |

|

B2

|

|

-

Courante - seconde Courante

|

|

4' 35" |

|

B3 |

|

-

Sarabande la Dangereuse

|

|

2' 12" |

|

B4 |

|

-

Gigue |

|

2' 16" |

|

B5 |

|

-

La Flore

|

|

2' 37" |

|

B6 |

|

-

Les Agrémens. Première et seconde

partie

|

|

4' 11" |

|

B7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gustav Leonhardt,

Harpsichord (Martin Skowroneck, 1962,

nach J. D. Dulcken, 1745)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Amsterdam (Holland) -

1971 |

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording

Supervision |

|

Dr. Thomas Gallia |

Dr. Alfred Krings

|

|

|

Engineer |

|

Sonart |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Harmonia Mundi (Basf)

| 20 20348-2 | 1 LP - durata 44'

40" | (p) 1971

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Deutsche Harmonia

Mundi | LC 00761 | 82876 70000 2 |

1 CD - durata 44' 40" | (c) 2005 |

ADD

|

|

|

Cover Art

|

|

-

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

"...

j'avoueray de bonne

foy que j'ayme

beaucoup mieux ce qui

me touche que ce qui

me surprend."

from

the forward to the Pièces

de clavecin I

A French composer who writes

no ballets is like an

Italian composer who has no

interest for the opera. None

of the works of François

Couperin was intended for

the stage; nothing was

written for orchestra-and

yet his contemporaries

admired him as organist,

harpsichordist, composer and

teacher. Descendents term

his contribution the "sum of

French music".

The respected office of

organist at St. Gervais was

reserved as early as 1679

for the eleven-year-old upon

the death of his father

Charles. His uncle Louis

Couperin had already been

active at this church; the

nephew assumed (entered upon

the office at seventeen).

Five years later he

published his two masses for

organ, which established the

fame of the composer. Upon

taking the position as

organist at the Chapelle du

roy in Versailles in 1693,

he attained the external

peak of his career. Spending

his entire life in Paris, he

was to become not only

teacher to the royal family,

but also mentor to a

generation of French

musicians. The fruits of

Couperin's pedagogic

engagement were made

manifest in 1716 with the

publication of the Art

de toucher le clavecin,

which he dedicated to the

young Louis XV. Bach used

this theoretical work, the

knowledge of which is the

foundation of the study and

performance of French music

for harpsichord, without

which, however, the

interpretation of German

music in the French style

must remain inadequate.

The life of the organist and

harpsichordist at Versailles

passed without crucial

turning points. Similar to

Bach, Couperin concentrated

during the last twenty years

of his life on the

collection and accurate

editing of his works. His

work is easily surveyable.

Several motets along with

some “versets", a few

elevations, and above all

the late, very expressive Lamentations

of Jeremias comprise

the entire extant body of

sacred music. The chamber

music consists mainly trios,

the older of which being in

the Italian style of sonatas

for 2 violins and basso

continuo.The younger vary in

orchestration and attempt in

their language to combine

Italian and French styles.

The title of a collection

from 1724 is typical: Les

Goûts réunis. Also in

the field of chamber music a

late work comes to represent

a culmination; the Pièces

de viole (1728),

written for the less and

less used viola da gamba.

Even during Couperin’s

lifetime, the Pièces de

clavecin enjoyed a

wide popularity. The

“ordres" of the published

pieces in four books

correspond only remotely to

the stricter forms of the

suites as they were composed

in Germany. They are for the

most part collected works

which were preferred in

earlier periods and from

which the performer might

chose. Although Couperin

used in the fifth ordre the

traditional plan with the

series Allemande, Courante,

Sarabande and Gigue, the

movements are nevertheless

often individual portraits

rather than parts of a

larger context. In the

seventh ordre the poetic

pictures are ordered

entirely one after the

other, possessing little

suggestive painting and

having usually short and

clear musical forms,

dance-like, with a floating

lightness even where the

dark registers of the

harpsichord are preferred.

In each of these movements

Couperin has, as he wrote,

an "objet" which he

continually repeated or

transformed. Thus the

metamorphoses of a musical

idea can be found in the

numerous Rondeaux, as well

as in the forms of the

Chaconne.They reflect

ideally the wish for a

"unité de sentiment" of the

French art.

The elegance of all these Pièces

recall the model of the

seventeenth-century French

lutenists who influenced so

permanently the harpsichord

style. The tendency to

arpeggi and free passages

becomes especially evident

in those seemingly

improvised Préludes

of the Art de toucher,

which Couperin intended as

introduction for his

"ordres”. Even his

contemporaries recognized

that Couperin was the

counterpart to a cold

virtuoso, as he appears

sometimes in

interpretations. The author

of a work which mirrors the

brilliant superfluousness of

French art and nonetheless

is capable of producing

deeply expressive sounds

speaks about this himself: "...

I confess in all

seriousness that I love

rnuch more that which

moves me than that which

surprises me".

|

|

|

|