|

|

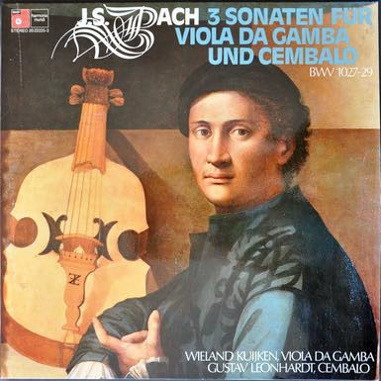

1 LP -

20 22225-3 - (p) 1974

|

|

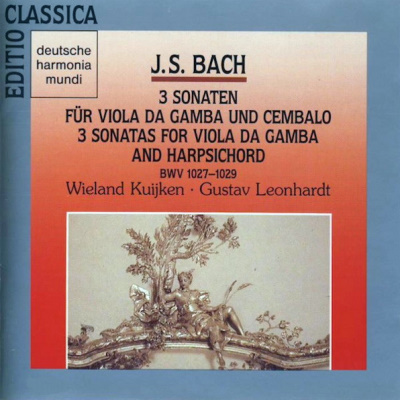

| 1 CD -

GD 77044 - (c) 1989 |

|

DREI SONATEN

FÜR VIOLA DA GAMBA UND CEMBALO

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

BACH (1685-1750) |

Sonate

G-dur, BWV 1027

|

|

13' 58" |

|

|

- Adagio

|

4' 03" |

|

A1 |

|

- Allegro ma

non tanto

|

3' 58" |

|

A2 |

|

- Andante |

2' 47" |

|

A3 |

|

- Allegro moderato |

3' 19" |

|

A4 |

|

Sonate

D-dur, BWV 1028 |

|

15' 48" |

|

|

- Adagio |

2' 02" |

|

A5 |

|

- Allegro

|

4' 01" |

|

A6 |

|

- Andante

|

5' 20" |

|

B1 |

|

- Allegro |

4'

25"

|

|

B2 |

|

Sonate

g-moll, BWV 1029 |

|

16' 11" |

|

|

- Vivace

|

5' 28" |

|

B3 |

|

- Adagio

|

6' 50" |

|

B4 |

|

- Allegro

|

3' 53" |

|

B5 |

|

|

|

|

|

Wieland KUIJKEN,

Viola da gamba (anon.

Süddeutschland, 18. Jahrh.)

Gustav LEONHARDT, Cembalo

(Martin Skowroneck, Bremen 1962,

nach J. D. Dulcken, Anvers, 1745)

Augenommen im tiefen Kammerton

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Schloß Wannegem-Lede

(Berlgien) - 15/17 maggio 1974

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording

Supervision |

|

Dr. Thomas Gallia |

Paul Dery

|

|

|

Engineer |

|

Sonart, Milano

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Harmonia Mundi (Basf)

| 20 22225-3 | 1 LP - durata 46'

26" | (p) 1974

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Deutsche

Harmonia Mundi | LC 00761 |

GD 77044 | 1 CD - durata 46'

26" | (c) 1989 | ADD

|

|

|

Cover Art

|

|

-

|

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

Bach probably

wrote his three sonatas for

viola da gamba and cembalo

between 1717 and 1723, while

he was Kapellmeister at the

Cöthen court. The reasons

are clear: Bach's employer,

Prince Leopold of

Anhalt-Köthen, was himself

an amateur gamba player.

Bach was probably thinking

of him when he included two

obbligato viola da gamba

parts in the 6th Brandenburg

Concerto. Solo sonatas for

the Prince's favourite

instrument were an obvious

bonus.

In the six years at Cöthen -

when Bach was in his middle

thirties - most of the

instrumental works came into

being: sonatas and concertos

in the Italian style, and

suites in the French style

for different instruments in

addition to the first book

of the Well-Tempered

Clavier. All forms of

instrumental music current

at the period were tried

out, to explore their limits

in ever new and different

ways. Bach's tremendous

imagination reveals itself

in his capacity to react to,

and transform, existing

forms, as even his

contemporaries recognized.

Indeed, even he was cantor

at St. Thomas in Leipzig -

and this is particularly

true of his instrumental

music - Bach nowhere broke

out of the established

musical forms of his time,

although he was able in the

partitas, variations and

fugues of the later period

to create a musical world

which combined mathematical

rules of proportion,

cabbalistic number-play, the

greatest freedom of

invention, daring harmonic

progression and depth of

expression. But thus far -

in Cöthen - these limits

have not yet been reached.

The traditional forms of the

"sonata da chiesa" with its

four movements (slow - fast

- slow - fast) and the

"concerto" (on Vivaldi's

model) with its three

movements (fast - slow -

fast) provide a basis in the

gamba sonatas for inventive

trio playing. The G major

sonata, however, must be

placed somewhat earlier,

particularly since it finds

an earlier form in the

sonata for two flutes and

bass. The viola da gamba has

taken over the part of the

second flute; the

transposition down an octave

makes the overall sound more

transparent.

The two other sonatas appear

more modern; the D major,

because, especially in the

second and fourth movements,

it most strongly breaks

through the principle pf the

"trio", and the G minor,

because in it the

three-movement concerto form

has been reached. Otherwise,

in some of their rhythmic

figurations and in their

instrumental treatment, both

sonatas are reminiscent of

the 3rd and 5th Brandenburg

concertos, which helps to

settle the question of when

they were written with some

precision. Particular

attention is drawn to a

reminiscence of the third

movement of the D minor

cembalo concerto in the

first movement of the G

minor sonata.

But all these points are of

a formal kind. If one thinks

of the early organ works,

bristling with genius, which

were able to put a

congregation in confusion

and which so much disturbed

the church elders in

Arnstadt, and if one

remembers the timeless works

of the later period, which

surge like erratic blocks of

highly intellectual art into

a period characterized by a

"style galant", then we must

regard our three sonatas,

like the Brandenburg

concertos, as being "up to

date". With their mixture of

elegance and thoroughness,

they make room for music

which was intended to

"delight the soul" and was,

for the connoisseur,

simultaneously "practice"

and "galanterie".

W.

W.

|

|

|

|