|

|

2 LPs

- 1C 157-16 9541 3 - (p) 1985

|

|

| 2 CDs -

GD 77040 - (c) 1990 |

|

MESSE H-MOLL

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

BACH (1685-1750) |

Messe

h-moll, BWV 232 |

|

|

|

|

KYRIE

|

|

18' 42" |

|

|

- Chor: Kyrie

eleison

|

9' 19" |

|

A1 |

|

- Duetto für

2 Soprane: Christe

eleison

|

5' 14" |

|

A2 |

|

- Chor: Kyrie eleison |

4' 09" |

|

A3 |

|

GLORIA

|

|

36' 07" |

|

|

- Chor: Gloria

in excelsis Deo / Et in

terra pax

|

6' 16" |

|

A4 |

|

-

Aria für Sopran: Laudamus te

|

4' 20" |

|

A5 |

|

- Chor: Gratias

agimus tibi |

2' 57" |

|

B1 |

|

- Duetto

Sopran / Tenor: Dominus

Deus

|

5' 51" |

|

B2 |

|

- Chor: Qui

tollis peccata mundi

|

3' 02" |

|

B3 |

|

- Aria für Alt: Qui sedes ad

dextram Patris

|

4' 52" |

|

B4 |

|

- Aria für Baß: Quoniam tu

solus sanctus

|

4' 42" |

|

B5 |

|

- Chor: Cum

Sancto Spiritu

|

4' 07" |

|

B5 |

|

CREDO |

|

32' 23" |

|

|

- Chor: Credo

in unum Deum

|

2' 27" |

|

C1 |

|

- Chor: Patrem

Omnipotentem

|

2' 03" |

|

C2 |

|

- Duetto

Sopran / Alt: Et in unum

Dominum

|

4' 54" |

|

C3 |

|

- Chor: Et

incarnatus est

|

3' 14" |

|

C4 |

|

- Chor: Crucifixus |

2' 50" |

|

C5 |

|

- Chor: Et

resurrexit

|

4' 02" |

|

C6 |

|

- Aria für

Baß: Et in Spiritum

Sanctum

|

5' 34" |

|

C7 |

|

- Chor: Confitebor

|

5' 09" |

|

D1 |

|

- Chor: Et

expecto |

2' 10" |

|

D2 |

|

SANCTUS -

Chor

|

|

5' 19" |

D3 |

|

OSANNA,

BENEDICTUS, AGNUS DEI ET

DONA NOBIS PACEM

|

|

18' 22" |

|

|

-

Doppelchor: Osanna |

2' 46" |

|

D4 |

|

- Aria für

Tenor: Benedictus

|

4' 10" |

|

D5 |

|

-

Doppelchor: Osanna |

2' 47" |

|

D6 |

|

- Aria für

Alt: Agnus Dei

|

5' 36" |

|

D7 |

|

- Chor: Dona

nobis pacem

|

3' 03" |

|

D8 |

|

|

|

|

|

Isabelle

Poulenard, Sopran

Guillemette Laurens, Mezzosopran

René Jacobs, Altus

John Elwes, Tenor

Max van Egmond, Baß

Collegium musicum van de

Nederlandse

Bachvereniging

|

LA PETITE BANDE

/ Gustav LEONHARDT, Leitung

- Sigiswald Kuijken, Alda

Stuurop, François Fernandez, Marie

Leonhardt, 1. Violinen

- Staas Swierstra, Natsumi

Wakamatsu, Enrico Gatti, 2.

Violinen

- Ruth Hesseling, Marleen Thiers, Viola

- Richte van der Meer, Rainer

Zipperling, Violoncelli

- Nicholas Pap, Kontrabaß

- Barthold Kuijken, Danielle

Etienne, Flöten

- Michel Henry, Marcel Ponseele,

Taka Kitazato, Oboe und Oboe

d'amore

- Danny Bond, Donna Hyry Agrell, Fagotte

- Claude Maury, Corno da caccia

- Friedemann Immer, Klaus Osterloh,

Kay Immer, Trompeten

- Glen Wilson, Orgelpositv

(Truhenorgel)

- Pierre Deboeck, Pauken

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Doopsgezinde Gemeente

Kerk, Haarlem (Holland) - 13/19

febbraio 1985

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording

Supervision |

|

Klaus L Neumann |

Thomas Gallia | Paul Dery

|

|

|

Engineer |

|

Sonart, Milano

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Harmonia Mundi (EMI

Electrola) | 1C 157-16 9541 3 | 2

LPs - durata 55' 02" - 56' 25" |

(p) 1985 | DIGITAL

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Deutsche

Harmonia Mundi | LC 0761 |

GD 77040 | 2 CDs - durata

55' 05" 56' 23" | (c) 1995 |

DDD |

|

|

Cover Art

|

|

Christuskopf,

Zisterzienserkirche in Viktring,

Kärnten, um 1400. ©

Buch-Kunstverlag Ettal

|

|

|

Note |

|

Eine Aufnahme des

Westdeutschen Rundfunks Köln. |

|

|

|

|

The B

minor Mass is Bach‘s

only Missa tota,

that is to say, his only

mass composition including

all of the parts of the Ordinarium

Missae: Kyrie,

Gloria, Credo,

Sanctus with Benedictus

and Osanna, as well

as Agnus Dei. The

history of its creation is

unique also within the

framework of Bach’s complete

oeuvre. A history which

extends from 1724, his

second year in Leipzig,

until the last days of his

life. Bach worked on the B

minor Mass and not on

the Art of the Fugue,

as had been previously

assumed, in the period

immediately before his death

(according to the latest

findings by Yoshitake

Kobayashi, Gottingen).

Bach composed the six-part Sanctus

(without Benedictus

or Osanna) already

for Christmas 1724. The Sanctus

being the section of the

Ordinary sung or played

(monophonic or polyphonic)

in the Lutheran church only

on high feasts. The Kyrie

and Gloria followed

in 1733. As the only two

Mass movements belonging to

the Sunday church service

they received the

designation Missa, as was

usual in Bach’s time. Bach

sent the parts for the Missa

along with a dedication

dated 27 July 1733 to the

newly invested Catholic

Elector Friedrich August II

of Saxony (concurrently King

of Poland as August III). In

the dedicatory letter he

requested the appointment to

the position of court

composer, which he however

received only in 1736.

Hans-Joachim Schulze, who

has published a facsimile

edition of the parts with

commentary (Stuttgart 1983),

has recently called into

question the prevailing

assumption that the Missa

was performed on 21 April

1733 during the devine

service held in St.

Nicolai’s, Leipzig, in

honour of the new Elector’s

succession to the throne.

Rather, it is more likely

that the parts were written

in Dresden in the hope of

receiving a performance

there. However there is of

yet no evidence of a

performance in Dresden. Only

towards the end of his life

did Bach form the Sanctus

of 1724 and the Missa

of 1733 into a Missa

tota through the

composition of the Credo,

the so-called Symbolum

Nicenum and the last

sections of the Ordinarium,

from Osanna through

Dona nobis pacem. We

don’t know what his

incentive was, nor is

anything known of a

performance of the complete

work. Certain is only a

performance of the Sanctus

in 1724, probably followed

by a further one at Easter

1727. A third performance

was possibly brought about

by the Bohemian Count

Sporck, who had borrowed the

original parts of this

movement (whereby they went

astray).

The unusual history of the B

minor Mass’s creation

led the noted Bach scholar

Friedrich Smend, editor of

the work for the Neue

Bachausgabe (1953), to

the conclusion that the B

minor Mass was not

considered by its creator to

be a complete work. Rather,

Bach, in his later years,

combined the individual

sections more or less at

random in the two partial

volumes, with four title

pages but without an overall

title. The first volume

contains the Missa,

the second the Symbolum

Nicenum, a new copy of

the Sanctus and

finally - following the last

title page - the remaining

pieces, from the Osanna

through Dona nobis pacem,

which Smend, in agreement

with Philipp Spitta, took to

be music for the Communion.

However it is hardly

possible not to recognize

that Bach completed the B

minor Mass to form a

unified work. This is shown

above all by the

reappearance of the Gratias

agimus from the Gloria

as a parody at the end of

the Mass in the Dona

nobis Pacem (this type

of self-parody also occurs

in Mass settings by other

Baroque masters) and by the

thematic relationship

between the Osanna

and the Pleni sunt coeli

of the Sanctus. In

addition it is also possible

to identify unifying formal

principles for the whole Mass,

so that there can be no

doubt as to the unity of

Bach’s Missa tota.

A word on the use of parody

technique, whose importance

in the B minor Mass

is just as great as in the Christmas

Oratorio! According

to current knowledge, only

eight from a total of 25

movements, or barely a third

(counting the Gloria in

excelsis with the Et

in terra pax as one

movement and the repeated Osanna

only once), can be

considered with certainty to

be original compositions.

They are the first Kyrie,

the second part of the Gloria

in excelsis (from

measure 100) and the ending

of the Gloria cycle

Cum sancto spiritu;

from the Symbolum

Nicenum the movements

Credo in unum Deum, Et

incamatus est, Confiteor,

and Et expecto, and

finally the Sanctus.

It is true the models for

only seven of the remaining

17 movements, for the Gratias

agimus, Qui tollis

peccata mundi, Patrem

omnipotentem, Crucifixus,

Osanna, Agnus Dei,

and Dona nobis pacem

have been identified. It is

therefore not inconceivable

that a few original

compositions are hidden

among the presumed parodies.

This of course does not

change the general view that

the B minor Mass consists

mainly of parody movements.

This should not give rise to

doubt as to the quality of

the music. Bach’s reusage of

a composition in connection

with an extensive

rearrangement quite often

approaches the level of a

new creation. This is

clearly shown, for example,

by the especially impressive

Agnus Dei, whose

model is the aria Ach

bleibe doch, mein liebstes

Leben, from the

Ascension oratorio (BWV 11).

Other older compositions on

the other hand practically

cried out for a renewed

usage, as occurred with the

opening movement from the

cantata Weinen, Klagen,

Sorgen, Zagen (BWV 12)

for the Crucifixus.

(This movement was already a

parody, making the Crucifixus

a parody second degree. The

common model is a

composition by Vivaldi with

the text Piango, gemo,

sospiro e peno, "the

love song of an unhappy

soul”, thus Bernhard

Paumgartner, who discovered

the concordance.)

The broad musical horizon in

which the B minor Mass’s

evolution took place is

shown by the parodies. Not

only the different stages of

the Leipzig years are

reflected therein, but also

the Weimar period (BWV 12

dates from this time)

exercises its influence. The

achievements of the Cöthen

years are felt in the

concertante movements Gloria

in excelsis Deo and Et

resurrexit. Thus, the

B minor Mass reflects

to a certain degree all of

Bach’s creative periods. If

we consider that Bach,

especially in the Credo,

repeatedly had recourse to

the Stile antico,

the old-fashioned polyphony,

and approached, for example,

in the Christe eleison,

the developing gallant

style, the conception of his

Missa tota broadens

into a universal expanse,

embracing past and present,

anticipating the future.

For all that, the genesis

and the elements of form and

style are in themselves not

of great importance, but

rather form the transparent

mantle surrounding the

spiritual substance. Yet, in

regard to the B minor

Mass, the question

arises, according to which

principles did Bach make use

of his stylistic resources

and formal elements. Whoever

listens to the work

carefully will ask himself,

according to which

fundamentals did Bach employ

chorus, aria and duet,

especially in the eight

movements of the Gloria

and in the nine movements of

the Credo. Thus the

disruption, apparently

without reason, of the

symmetry, chorus - solo -

chorus - etc., in the Gloria

could give rise to an

impression of arbitrariness.

By listing the movements as

shown below, the well

thought-out, artistic form

of the cycle becomes

apparent.

At the top stands the

angels’ song of praise in

the night before the

nativity (Luke 2, 14),

followed by an

old-established liturgical

text, the so-called Laudamus.

The latter has in the B

minor Mass the

following form: Beginning

and end are each made up of

an aria im mediately

followed by the doxology.

The aria texts are related

by the repeated word te

(thee) in the first and the

triple tu solus

(thou only) in the second.

Bach achieved the expression

of the text’s significance

through the choice of the

aria. The single vocal part

symbolizes the one eternal

God, to whose glory the

following hymn of praise by

tutti choir and orchestra is

intended. In the central

position of the Gloria

cycle, symbolizing the

Trinity, follows a

three-movement

supplicatiorn, in whose

centre - and thus in the

centre of the whole cycle -

stands the chorus Qui

tollis peccata mundi,

the image of the crucified.

This chorus is flanked by a

duet signifying the

humiliation of God in Jesus

Christ, and by the aria Qui

sedes ad dextram Patris.

The duet symbolizes God’s

transformation into human

form, the second person of

the Trinity (as in the Christe

eleison of the

three-part Kyrie).

This is also symbolized by

the tonality of the

subdominant, G major, as

opposed to the D major of

the doxology framework. The

aria stands for the unity of

the exalted Lord with God

the Father. Even more

precisely conceived, yet

still closely related to the

form of the Gloria,

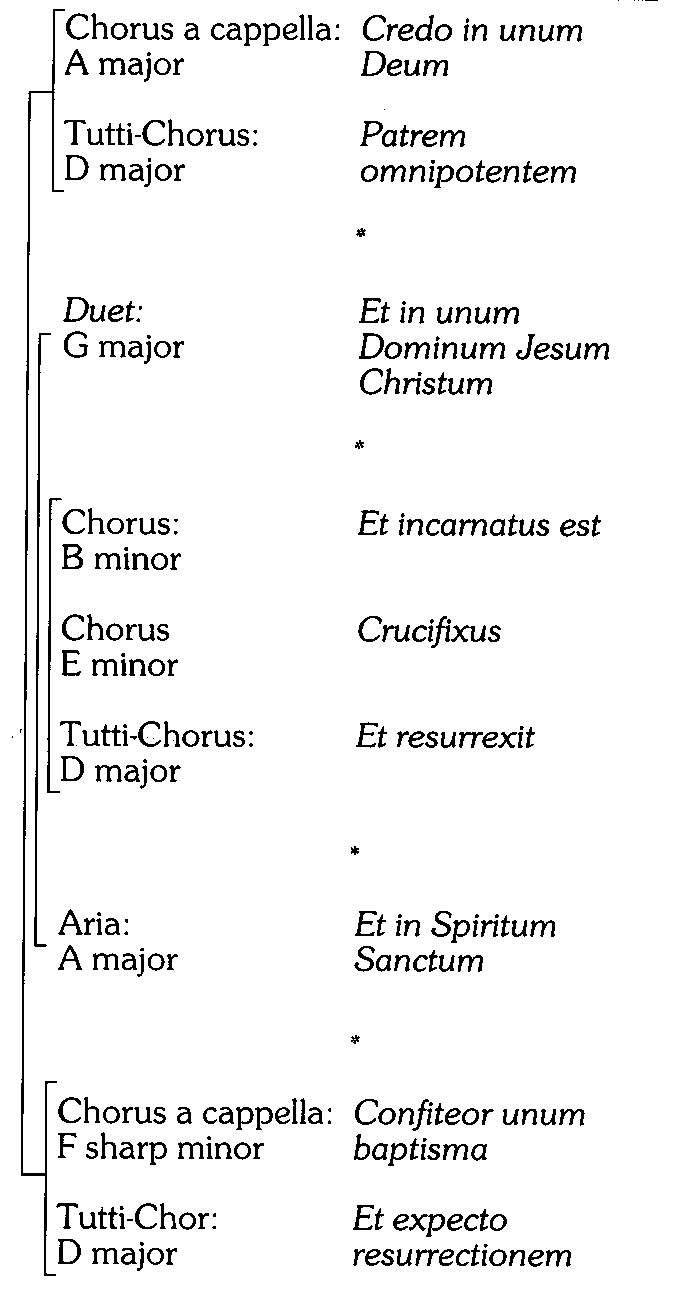

is the Symbolum Nicenum,

as shown in the following

table:

It immediately strikes the

eye, that this cycle

contains only two soloistic

movements, these are found

at the beginning of the

second and third articles of

faith. Once again, the

statement of God’s

transformation into human

form is represented by the

duet, also here in the

subdominant, G major. The

article dealing with the

Holy Ghost within the

Trinity is introduced by an

aria, which this time is in

the dominant, A major. Also

this cycle is inclosed in a

framework, here made up of a

capella choruses followed in

each case by a tutti

doxology. (In the Credo

in unum Deum, a surely

symbolic seven-voice fugue

on a theme in seven entries,

two violins are ”compelled”

to help out. ) In addition,

both a cappella choruses

contain a medieval Gregorian

chant, still in use in both

Christian churches. In the

first chorus this chant is

used as the fugue theme, in

the second as a canon and

them as the tenor cantus

firmus, both in the

intentionally old-fashioned

Stile antico. Here

also exists a linguistic

connection: the words ”unum

Deum" in the first chorus

correspond to the words

"unum baptisma” in the Confiteor.

Also in this cycle the

attention is directed

towards the crucified in the

central position by the

order of the middle

movements, Et incarnatus

est, Crucifixus

and Et resurrexit.

The significance of the order

is further underlined by the

tonalities: the B minor of

the chorus Et incarnatus

est is followed by the

E minor of the Crucifixus,

the parallel of the

subdominant as the sign of

utmost humiliation, whereby

the chorus Et resurrexit

begins with the greatest of

contrasts in D major. That

Bach consciously intended

this axial-symmetrical order

for the cycle can be

verified by the fact that it

received its final form only

after a revision of the

original version. It can be

only mentioned here in

passing that such a

formation is a

characteristic Baroque

stylistic feature.

Characteristic of Bach’s

artistic personality is the

always present interest in

art for art’s sake, in music

as ars, that is to

say, in the search for all

conceivable possibilities in

regards to form, setting,

virtuoso technique,

instrumentation. etc. This

is shown, for example, by

his use of different

concertante instruments in

the various solo movements

of the Gloria cycle

to demonstrate the full of

musical possibility. This

never occurs arbitrarily,

but rather always analogous,

where possible symbolic, as

in the use of a brass

instrument in the bass aria

Tu solus sanctus. The

brass instruments having

been considered

representative of the

heavenly realm. Or in the Crucifixus

chorus, whose model already

contains a lamento figure of

a chromatically descending

fourth, which sounds twelve

times, to which Bach here

added a 13th period in which

the continuo enters only at

the words ”Et sepultus est”,

leading then to G major. A

unique realization of the

death-like silence on

Golgotha, behind which the

unspoken "It is done" can be

perceived. Thus, the highest

compositional mastery

becomes transparent for the

expression of religious

affirmation. As unmistakable

as the formal relationship

is between the two cycles of

the B minor Mass,

the Symbolum Nicenum

represents not just a

continuation of the Gloria,

but rather, in the

completion of the work, a

concentrated, spiritualized

intensification. Even

assuming that the impulse

for the work’s completion

was given by some external

incentive, Bach clearly had

more in mind with his only Missa

tota (actually a Missa

concertata exploring

all of the contemporary

compositional techniques)

than the fulfilment of a

commission. It is the wish

to bequeath posterity an

”idea-work of art”, on the

one hand as a representation

of the humanly possible in

the realm of composition,

and on the other, as a

symbolic portrayal of the

divine service’s all

embracing ideal, in its

timelessness and

supra-denominationalism.

Bach’s late instrumental

works, characteristic of the

last decade of his life, can

hardly be appreciated by the

modern observer without

taking the B minor Mass

into consideration. It

thus becomes impossible to

see in these late

instrumental works a turning

away from his profession as

cantor or from his duties

within the church. For all

that, Bach’s handling of

music as art also resulted

in a theological

realization, in the

understanding of the general

bass as ”the most complete

foundation of music“, whose

“last and final justification

can be none other than the

honour of God and the

recreation of the soul” (Fr.

E. Niedt, Grülindlicher

Unterricht des

General-Basses). This

meant for Bach, both freedom

and restriction. Bach’s opus

ultimum, the

completion of the B

minor Mass, has to be

understood as the sum of his

life.

After 1750, the autograph

score of the work came into

the possession of Bach’s

second son, Carl Philipp

Emanuel, who performed the

Credo in a "Concert for the

medical alms-house” in 1786.

This being an indication

that he considered the Credo

to be the most important

part of the Mass. In

the inventory of his estate

from 1790, the manuscript is

listed as "the large

Catholic Mass”; if this

designation has any basis,

is not known. At first no

buyer could be found for the

valuable manuscript. Only in

1805 was it acquired by the

Swiss writer and music

publisher Hans Georg Nägeli,

who then spoke of ”the

greatest work of art of all

times and every culture”.

His planned edition of the Mass

came to fulfilment only in

1845 under the supervision

of his son, Hermann. The

name, Great Mass in B

minor, appeared here

for the first time,

undoubtedly in order to

place it on the same level

with Beethoven’s Missa

solemnis. The Händel

biographer Friedrich

Chrysander later acquired

the autograph score for the

Bach-Gesellschaft, founded

in 1850, who in turn sold it

to the Royal Prussian

Library, Berlin, in 1861. At

present, the manuscript

belongs to the holdings of

the Staatsbibliothek

Preussischer Kulturbesitz in

West Berlin.

Independent of the fate of

the autograph score, efforts

were made already at the

beginning of the 18th

century to prepare the Mass,

copies of the score having

been made early on. Carl

Friedrich Zelter was the

first, having occupied

himself with the work, since

1811, at the Berlin

Singakademie. It was here

that the work was first sung

in its entirety, however not

in public, since it was

considered too difficult. In

1834, Zelter’s successor

Carl Friedrich Rungenhagen

presented the complete work

to the general public for

the first time, on two

evenings; partial

performances having already

taken place in various

German cities since 1828.

Yet, only after the B

minor Mass appeared in

the first complete edition

of Bach’s works 1856 in an

inadequate version, since

the autograph score was not

available, 1857 in a revised

edition - were the

conditions present for the

inclusion of the work in the

repertoires of the most

capable oratorio choirs. The

Berlin Singakademie alone

realized 57 performances up

until the beginning of the

Second World War. Renditions

of the B minor Mass

were however always

exceptional events and are

so even today, even if the

number of performances has

grown greatly in recent

times; every conductor sees

in the presentation of the B

minor Mass the high

point of his career. This

development is also evident

abroad and within the

Catholic church. Today, the

B minor Mass belongs

to humanity, irrespective of

denomination or nationality;

it is considered to be the

pinnacle of musical culture.

One can only wish that along

with its unique sonority,

its essence also be

increasingly understood.

G.B.

|

|

|

|