|

|

3 CDs

- RD 77848 - (p) 1990

|

|

| MATTHÄUSPASSION |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

BACH (1685-1750) |

Matthäus-Passion,

BWV 244

|

|

|

|

|

Erster

Teil |

|

74' 40" |

|

|

- No. 1-35

(1-29 Neue Bach Ausgabe) |

74' 40" |

|

1-1/29 |

|

Zweiter

Teil |

|

97' 42" |

|

|

- No. 36-61 (30-52 Neue Bach

Ausgabe)

|

51' 10" |

|

2-1/23 |

|

- No. 62-78 (53a-68 Neue Bach

Ausgabe)

|

46' 32" |

|

3-1/16 |

|

|

|

|

|

Solisten

- Christoph Prégardien,

Tenor (Evangelista)

- Max van Egmond, Bass

(Jesus)

- René Jacobs, Alto

(Chor I)

- Marcus Schäfer, Tenor

(Chor/Chor I)

- Klaus Mertens, Bass

(Chor I)

- David Cordier, Alto

(Chor II)

- John Elwes, Tenor

(Chor II)

- Peter Lika, Bass

(Chor II)

Soliste des Tölzer

Knabenchor:

- Christian Fliegner, Sopran

(Chor I)

- Maximilian Kiener, Sopran

/Chor II)

TÖLZER KNABENCHOR /

Gerhard Schmidt-Gaden, Leiter

MANNERCHÖR VON LA PETITE BANDE

LA PETITE BANDE / Sigiswald

Kuijken, Leiter

Gustav LEONHARDT, Gesamtleitung

|

Orchestra I

- Sigiswald Kuijken, Konzertmeister

- Ryo Terakado, Marie Leonhardt,

Jean-Paul Burgos, Violin I

- Irmgard Schaller, Anette

Sichelschmidt, Roberto Crisafulli, Violin

II

- Marleen Thiers, Simon Heyerick, Viola

- Richte Van Der Meer, Emmanuel

Balssa, Violoncello

- Nicholas Pap, Violone

- Pierre Hantaï, Orgel

- Barthold Kuijken, Frank Theuns, Flauto

traverso

- Paul Dombrecht, Marcel Ponseele, Oboe

- Wieland Kuijken, Viola da

gamba

Chor I

- Tölzer Knabenchor, Sopran und

Alto

- Ludy Vrijdag, Hans Latour, Jan

Willem Van der Wey, Joseph Pettit, Tenor

- Job Boswinkel, Piet Brummer, Jef

Gulinck, Wouter Schuller, Bass

····················

Orchestra

II

- François

Fernandez, Konzertmeister

- Alda Stuurop, Staas

Swierstra, Myriam Gebers,

Violin I

- Mihoko Kimura, Cathérine

Girard, Xavier Julien-La

Ferrière, Violin II

- Otsu Mutsumi, Galina

Zinchenko, Viola

- Rainer Zipperling, Tanya

Tomkins, Violoncello

- Eric Mathot, Violone

- Siebe Henstra, Orgel

- Marc Hantaï, Serge

Saitta, Flauto

traverso

- Taka Kitazato, Yannis

Papayannis, Oboe

Chor

II

- Tölzer Knabenchor, Sopran

und Alto

- Jan Van Elsacker, Ulrich

Löns, Paul Van der Bempt,

Stephane Leys, Tenor

- Christophe Dobmeier,

Thomas Dobmeier, Paul Van

den Berghe, Pieter Coene,

Bass

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Lutherse Kerk,

Haarlem (Holland) - 1/8 marzo 1989

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording

Supervision |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

Engineer |

|

Stephan Schellmann |

Andreas Neubronner

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Nessuna

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Deutsche Harmonia

Mundi (BMG) | LC 0761 | RD 77848 |

3 CDs - durata 74' 40" - 51' 10" -

46' 32" | (p) 1990 | DDD |

|

|

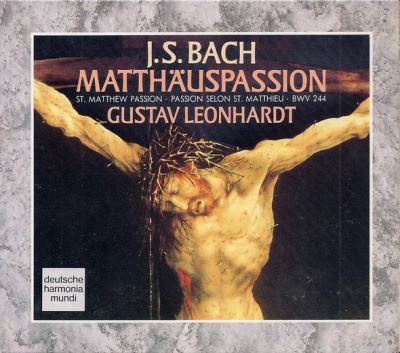

Cover Art

|

|

Matthias Gruenewald,

Isenheimer Altar: "Kreuzigung"

(c.1513-15115), Colmar,

Unterlinden Museum

|

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

BACH:

PASSION ACCORDING TO ST.

MATTHEW

“With

this work a new world opened

up to us“, wrote the actor

singer Eduard Devrient,

recalling the momentous

revival of the St.

Matthew Passion some

forty years earlier in 1829,

when he was joined by

Mendelssohn, then barely out

of his teens yet fully able

and willing to shoulder the

burden of a stupendous

musical challenge. Bach’s

masterpiece was already one

hundred years old but could

look back on little more

than one or two

unsatisfactory performances,

scant recognition, and not a

note in print.

The purifying freshness of

that deep-frozen music, as

apparent now as it was to

Devrient’s fellow-performers

and listeners, stems mainly

from elements to which he

rightly called attention:

“That the impersonation of

the several characters of

the Gospel by different

voices formed the core of

the work struck us with deep

amazement, the antiquity of

this practice in old church

music being long forgotten.

The dramatic treatment that

arose from it, the

overwhelming power of the

choruses, above all the

wondrous declamation of the

part of Christ... had with

every rehearsal increased

our astonishment and

admiration at the greatness

of the setting.“

Bach’s bedrock, solid and

deep, may correspond to a

custom first indicated in

liturgical manuscripts of

the late 13th century, such

as an English (Sarum)

Gradual in the library of

the Conservatorio di Musica

at Parma. The text of the

Passion is there divided

among five singers, with a

separate voice for that of

Christ on the cross. An even

more important innovation

occurs in a manuscript

compiled in the 1430s and

associated with St. George’s

Chapel, Windsor. In the

Passions according to St.

Luke and St. Matthew, the

words of Christ's followers

and adversaries are set for

the first time in three-part

harmony. As for the dramatic

urgency of Bach’s

double-choir settings, a

notable foreshadowing of

this is found in a late

15th-century Passion

(Modena, Estense Library)

whose turba (crowd)

sections are divided between

two volumes, one for each

side of the choir.

Subsequent Passion settings

assumed a wide variety of

forms and styles. Some

presented the entire text,

including narration, in

simple or complex polyphony,

while others alternated a

sung narrative with the

crowd sections in harmony.

In addition to the

individual texts of the

Gospels, there was a also

available a summa

Passionis consisting

of a conflate of all four,

and this was often set to

music in Latin or German.

The Protestant tradition

gained much from the

attentions of Johannes

Walter, Antonio Scandello,

and Joachim à Burck in the

16th century, and was even

more greatly enhanced by the

later settings of Melchior

Vulpius, Christoph Schultze,

and above all Heinrich

Schütz. His three Passions,

memorable for their

occasionally Italianate

harmonies and their highly

expressive recitative tones,

stand in a class of their

own.

Although Bach could have

chosen from at least four

main types and styles of

Passion music, he was

unswerving in his devotion

to the Passion oratorio,

which most nearly approached

operatic style and laid

great emphasis on original

texts, supplied in this

instance by Picander. The St.

Matthew Passion was

first performed at St.

Thomas Church, Leipzig, on

Good Friday, 15 April 1729.

Some scholars postulate a

première two years earlier,

in 1727, and it is indeed

possible that certain

movements originated in an

earlier Passion dating from

the Weimar years.

The lasting impression it

made on the composer Ethel

Smyth, studying in Leipzig

in 1879, may well have been

typical of the annual

performance at St. Thomas

Church, and is best summed

up in her own words. “I

count it as one of the great

privileges vouchsafed me

that I learned to love the Passion

in that place of places, the

prestige and acoustic

properties of which make up

for the dreariness of its

architecture. In one of the

side galleries, close up to

the orchestra, which was

grouped aloft in front of

the organ, sat the Thomaner

schoolboys, representatives

of the very choir of which

Bach was Cantor. I suppose

realizing these things has

something to do with it, but

never, so it seems to me, is

the Chorale in the opening

chorus so overwhelming as

when trumpeted forth with

the pride of lawful heirs by

the Thomaner Chor.

“I despair of giving an idea

of the devoutness of the

audience. Generally

speaking, most of the

inhabitants of Leipzig,

including nearly everyone I

knew, were either

exceedingly conventional

churchgoers or unbelievers,

but on this occasion the

dull mist of religious

indifference appeared to

lift for the time being. It

was not only that the church

seemed flooded with the

living presence of Bach, but

you felt as if the Passion

itself, in that

heart-rending, consoling

portrayal, was being lived

through as at no other

moment of their lives by

every soul in the vast

congregation.“

In this recording of the Passion

we enjoy a degree of

authenticity not remotely

possible in the previous

century. This is mainly,

although not exclusively,

due to a correct Instrumentarium

and techniques of

performance, all of which

are here scrupulously

observed. In the woodwind

section, for example, Bach

calls for a crossflute (flauto

traverso) in d’,

except for the opening

movement of Part 2 when ’low

fourth’ flutes must have been

used in order to take care

of the occasional lower

notes. The vibrant and

metallic sound of the oboe

da caccia helps to

express tragedy and anguish,

as when the dark agony of

Gethsemane is portrayed (no.

19), when Christ stands

condemned before Pilate

(nos. 48 and 49) or hangs

upon the cross (nos. 59 and

60), or finally at the Tomb

(no. 65).

Bach’s use of the oboe

d’amore is no less

imaginative, especially in

the soprano recitative and

aria nos. 12 and 13

(“Wiewohl mein Herz“; “Ich

will dir mein Herze

schenken“), where the two

veiled-sounding instruments

in thirds express to

perfection the close ties

between Mankind and the

Savior, moving from

heartfelt tears to a true

commingling of grace and

devotion. If there is one

other instrument whose

obbligato must have given

Bach’s audience cause to

wonder it is surely the

viola da gamba, familiar

enough in a chamber context

yet almost wholly unknown in

Passion music. Perhaps it

was played by a welcome

visitor from Cöthen,

Christian Ferdinand Abel,

who was a member of the

musical staff there, and

whose son Carl Friedrich

would be known in London as

one of the last virtuosi on

that instrument. The color

it lends to the bass aria

“Komm, süsses Kreuz“ (no.

57) could never be supplied

by a violoncello, for in

range of compass and emotion

it is unsurpassed.

These unusual instruments

are matched and balanced by

others of remarkable

sonority and beauty, so that

together with the rich

continuo section Bach’s

intentions are accurately

and persuasively realized.

The sound of the boys‘ choir

also contributes in a very

special way to this modern

yet historical evocation of

a timbre that enables us to

share his thoughts and ideas

about one of the noblest

themes he ever ventured to

interpret for us.

Denis

Stevens

|

|

|

|