|

|

1 CD -

RD 77923 - (p) 1990

|

|

| WERKE FÜR

CEMBALO |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Jakob

FROBERGER (1616-1667) |

Allemande,

Lamentation sur ce que J'ay été volé

- (aus Suite No. 14)

|

|

3' 20" |

1 |

|

Toccata

No. 9

|

|

1' 57" |

2 |

|

Canzon

No. 2

|

|

5' 36" |

3 |

|

Suite No.

30

|

|

7' 28" |

|

|

- Plainte

faite à Londres pour passer

la Melancholie

|

3' 13" |

|

4 |

|

- Gigue

|

1' 15" |

|

5 |

|

-

Courant

|

1' 14" |

|

6 |

|

- Sarabande

|

1' 46" |

|

7 |

|

Capriccio

No. 10

|

|

6' 21" |

8 |

|

Ricercar

No. 5

|

|

3' 29" |

9 |

|

Suite

No. 2

|

|

7' 17" |

|

|

- Allemanda |

2' 59" |

|

10 |

|

-

Courant |

1' 24" |

|

11 |

|

- Sarabanda

|

1' 32" |

|

12 |

|

- Gigue |

1' 22" |

|

13 |

|

Toccata No. 10

|

|

3' 17" |

14 |

|

Fantasia No. 4 sopra Sollare

(sol, la, re,

lascia fa re

mi)

|

|

4' 08" |

15 |

|

Toccata No. 14

|

|

3' 09" |

16 |

|

Lamentation

- faite sur la mort tres douloureuse de Sa

Majesté Imperiale, Ferdinand le troisième:

et joue lentement avec discretion

|

|

5' 49" |

17 |

|

Tombeau faict à Paris sur

la mort de

Monsieur

Blancrocher

|

|

5' 18" |

18 |

|

|

|

|

|

Gustav LEONHARDT,

Cembalo (Bruce Kennedy, 1985,

nach M. Mielke, Berlin 1702-1704?)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Lutherse Kerk,

Haarlem (Holland) - 15/16 giugno

1989

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording

Supervision |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

Engineer |

|

Stephan Schellmann

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Nessuna

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Deutsche Harmonia

Mundi (BMG) | LC 0761 | RD 77923 |

1 CD - durata 56' 58" | (p) 1990 |

DDD |

|

|

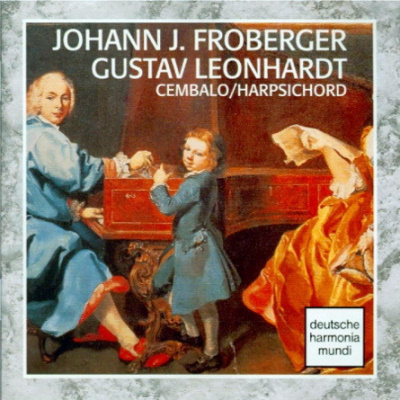

Cover Art

|

|

Burkhard Tschudi

(Burkat Shudi), Gründer der

englischen

Cembalo/Pianofortefabrik - Gemälde

c.1744/45, attr.: Philipp Mercier.

|

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

Froberger:

Harpsichord works

Although

many details in the life of

Johann Jakob Froberger

(1616-1667) are unclear, and

although it seems very

likely that a considerable

number of his works has been

lost, we know for certain

that his contemporaries

regarded him as the most

important German keyboard

composer of the 17th

century. This opinion even

continued to enjoy

widespread acceptance well

into the 18th century. J .S.

Bach, for example, came to

know Froberger’s work from

manuscript scores, while the

historian Adlung wrote in

his “Anleitung zu der

musikalischen Gelahrtheit“

(Handbook of musical

learning, 1758): “The late

Bach of Leipzig always held

Froberger in high esteem,

although he is already

somewhat old-fashioned“.

Other composers who

evidently learnt from

Froberger included Handel,

Kirnberger and even Mozart.

Notwithstanding, it is

certainly strange, to say

the least, that only two (!)

of Froberger’s works were

actually published during

his lifetime, namely the

Hexachord Fantasy, which

appeared in Athanasius

Kircher’s “Musurgiz

Universalis“ (Rome 1650),

and one (or more?) work(s)

in François Roberday’s

“Fugues et Caprices“ of

1660, a volume that also

contained works by

Frescobaldi. Up to the end

of the 17th century,

Froberger’s works were known

almost without exception

from manuscript, and the

most important editions were

not brought out until the

1690s by Bourgeat in Mainz

(1693) and by Roger et

Morrier in Amsterdam (1697).

From this we can conclude

that Froberger was

considered to be ’modern’

even thirty years after his

death. In fact, the

composer’s own attitude to

the publication of his works

may well have played its

part. The Duchess Sibylla of

Württemberg, who had her

residence in Héricourt in

the county of Montbéliard,

and was a close friend of

Froberger’s, had to promise

him “not to give anyone any

of my music..., for many

people wouldn’t know how to

treat it, and would thus

spoil it“. In the Duchess’s

opinion, a harpsichordist

would only be able to pick

up Froberger’s personal “à

discrétion“ style of playing

by learning “grif vor grif“,

i.e. putting one finger in

front of another, as

Froberger himself had done.

The importance of

Froberger’s contribution to

the development of musical

style is evident from the

interest that the musical

public took in his works in

the 17th and 18th centuries.

For Froberger was not only

the first German composer to

concentrate to an equal

degree on both the

harpsichord and the organ;

he was also the most

cosmopolitan figure among the

harpsichordists of his time.

These two facts had a

fundamental influence on his

musical style. A

contributing factor to the

international richness of

his music was the thorough

training he underwent in the

Stuttgart court orchestra

under the direction of his

father, the Hofkapellmeister

Basilius Froberger. His

father introduced him to the

music of Josquin Desprez as

well as to that of

contemporary German, English

and Italian composers such

as Lechner, Böddecker,

Morell, Franchini and

Marini.

After Froberger’s

appointment c. 1637 as court

organist to Emperor

Ferdinand III in Vienna, he

spent four years studying

with the famous organist

Girolamo Frescobaldi in

Rome, where he met

Carissimi, Kircher and

Michelangelo Rossi. The

influence these composers

had on him is reflected in

his 23 toccatas, 14

ricercares, 6 canzonas, 7

fantasias and 18 capricci.

In stylistic terms,

Froberger was also

influenced by the Dresden

organist Matthias Weckmann

as a result of musical

competitions organised

between them (from 1641 to

1648). Thanks to his

friendship with Weckmann,

Froberger also came into

contact with the North

German organ school, while

his travels in France

(including a visit to Paris

in 1652) brought him into

contact with the lutenists

Denis Gaultier, Gallot,

Blancrocher and with Louis

Couperin, uncle of FranÖois.

There can be no doubt that

these encounters left their

mark on Froberger’s thirty

keyboard suites, e.g. the

typical style brisé

(literally, broken style) in

his allemandes, and his

fondness for programmatic

titles, such as “Tombeau

faict à Paris sur la mort de

Monsieur Blancrocher“. This

work and the two

“Lamentations“ are among

Froberger’s most touching

works: they express deep

personal suffering in a

melancholy combination of C

minor and F minor, full of

bitter dissonances.

Clemens

Romijn

Translation:

Clive R. Williams

|

|

|

|