|

|

1 CD -

RD 77924 - (p) 1991

|

|

MASTERWERKE

FRANZÖSISCHER CEMBALOMUSIK

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Jean-Philippe

RAMEAU (1683-1764) |

Pièces

de Clavecin

|

|

|

|

|

- Les

tendres plaintes

|

|

3' 11" |

1 |

|

- La

Follette

|

|

1' 27" |

2 |

|

-

L'Entretien des Muses

|

|

5' 30" |

3 |

|

- Les Tourbillons

|

|

1' 48" |

4 |

|

-

Menuets

|

|

2' 49" |

5 |

|

- Sarabande

|

|

2' 27" |

6 |

|

-

L'Enharmonique

|

|

6' 07" |

7 |

| Gaspard LE ROUX (c.1660-c.1707) |

Suite

F-Dur

|

|

|

|

|

- Prélude |

|

1' 16" |

8 |

|

-

Allemande |

|

3' 05" |

9 |

|

- Courante

|

|

1' 30" |

10 |

|

- Menuet |

|

0' 55" |

11 |

|

- Chaconne |

|

3' 54" |

12 |

| Pancrace ROYER (1705-1755) |

Pièces

de Clavecin |

|

|

|

|

- Les tendres sentiments

|

|

4' 51" |

13 |

|

- La Majesteuse

|

|

2' 54" |

14 |

|

- La

Sensible |

|

3' 58" |

15 |

| Jacques DUPHLY (1715-1789) |

Pièces

de Clavecin |

|

|

|

|

- Courante c-moll

|

|

5' 26" |

16 |

|

-

Menuets c-moll

|

|

3' 27" |

17 |

|

- La

Du Buq

|

|

3' 56" |

18 |

|

- Les

Colombes, Rondeau

|

|

3' 51" |

19 |

|

- La

De Vancanson

|

|

2' 34" |

20 |

|

- La

Pothoüin, Rondeau

|

|

5' 48" |

21 |

|

|

|

|

|

Gustav LEONHARDT,

Cembalo (Nicholas Lefebure, Rouen

1755)

Equal temperament, a = 410 Hz.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Lutherse Kerk,

Haarlem (Holland) - 22/23 novembre

1989

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording

Supervision |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

Engineer |

|

Stephan Schellmann

(Tritonus/Stuttgart)

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Nessuna

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Deutsche Harmonia

Mundi (BMG) | LC 0761 | RD 77924 |

1 CD - durata 71' 02" | (p) 1991 |

DDD |

|

|

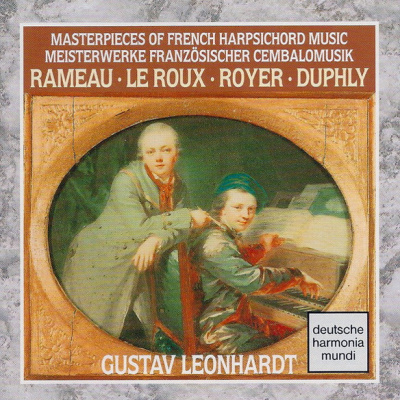

Cover Art

|

|

Heinrich Füger

(Heinrich Friedrich), 1751-1818

"Selbstbildnis des Küstlers mit

seinem Bruder Johann Gottlieb",

c.1769, Berlin (Ost),

Nationalgalerie

|

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

French

Harpsichord Music -

Rameau, Le Roux, Royer

& Duphly

In

the second half of the 17th

century, when the first

concerts outside court

circles were given in

private houses, professional

musicmaking beyond the

confines of Versailles became

properly organised for the

first time. Well-known

lutenists and

harpsichordists invited

friends, and colleagues (and

soon after members of the

nobility as well) to their

homes, in order to present

an especially gifted singer

or keyboard virtuoso. These

musical ‘soirées’ were

initially organised by the

musicians themselves, but

soon began to be put on by

various noblemen who

regularly frequented the

royal court. In this way,

they were able to introduce

music that they had heard in

private at Versailles to a

wider public. This

development played a central

role in making the

harpsichord repertoire

better known, and was of

such great importance

because music at court went

into a kind of hibernation

after the death of Louis XIV

in 1715, for whom music

represented an essential

enrichment of French

culture. It’s true that his

successor Louis XV did

rehabilitate the musical

tradition at court, but he

proved to be a patron with

considerable shortcomings,

regarding music as something

of merely decorative value.

This situation was

alleviated during the

gradual decline of royal

patronage by two passionate

music-lovers: Le Riche La

Pouplinière - an industrious

government minister who was

wealthy enough to maintain

one of the best orchestras

of Paris, and could afford

the services of composers

and conductors such as

Rameau, Stamitz and Gossec -

and Madame de Pompadour, the

mistress of Louis XV, who

actually put on her own

private concerts, thus

ushering in a new fashion in

Paris which was adopted by

many of the city’s

distinguished families. In

addition, public concerts

were organised for the first

time, with the agreement of

the king: they took the form

of so-called “Concerts

spirituels”, which were

inaugurated in 1725 in the

Jardin des Tuileries near

the Louvre.

While Rameau was in charge

for 22 years of the

orchestra of the financier

La Pouplinière, whose wife

was one of Rameau’s ardent

admirers, the “Concerts

spirituels” were directed

from 1748 to 1762 by his

fellow harpsichordist Royer.

It’s strange that Rameau

wrote hardly anything else

specifically for the

harpsichord, apart from the

“Pièces de clavecin en

concerts” (1741), “La

Dauphine" and the dances for

“Les Indes galantes”, after

he embarked on his career as

an opera composer with the

performance of “Hippolyte et

Ericie” in the house of La

Pouplinière. (At which time

he was already fifty years

old!) Rameauls 65

harpsichord works were

published in four volumes in

1706, 1724, ca. 1726 and

1741. Whereas stylised

dances appropriate to the

music of the Grand

siècle occupied pride

of place in the first

volume, the lion's share of

the suites was taken in the

later volumes by

characteristic genre pieces.

A similar change of

direction, which was coupled

with the adoption of Italian

stylistic elements and in

particular with the influence

of sonata form (the true

counterpart to the suite)

can be observed in the

harpsichord works of

Rameau’s elder colleague,

Francois Couperin.

Rameau’s suites show him to

be a master of the art of

naturalistic

characterisation, as for

example in his rhapsodic

piece “Les Tourbillons": he

described this work in a

letter as a depiction of

“clouds of dust whirled up

by gusts of wind”. Rameau's

more contemplative side

emerges most appealingly in

“L’Entretien des Muses”,

while “L'Enharmonique”

displays striking and daring

chromatics, both bold and

graceful.

The work recorded here cover

some sixty years in the

history of French

harpsichord music, as is

pleasingly illustrated by

the inclusion of the F major

suite by Gaspard Le Roux as

a kind of culmination of the

keyboard tradition of the Grand

siècle. Le Roux is

mentioned in contemporary

literature in the same

breath as Lebègue, Francois

Couperin and D’Anglebert,

and his popularity outside

France is illustrated by a

pirate edition of his

“Pièces“ brought out by

Roger in Amsterdam in 1705.

Le Roux died at roughly the

same time as Rameau was

publishing his first volume

of harpsichord suites. Le

Roux’s “Pièces” consist of

just three works, and they

do not contain any dances.

The preludes seem somewhat

archaic for the time as a

result of their notation in

unrhythmised semibreves,

thus recalling models in the

work of François Couperin’s

uncle Louis. The preludes of

Le Roux, however, are

considerably more simple.

The allemande is stately and

dignified, while the

expansive chaconne seems

very serious, and is full of

rich harmony.

The importance of Nicolas

Pancrace Royer lies first

and foremost in the fact

that, as director of the

“Concerts spirituels”,

he drew the public’s

attention once more to older

works by composers like

Carissimi and Gilles that

had since been forgotten.

However, Royer was also

responsible for significant

innovations in the concert

repertoire, performing works

by composers such as Hasse,

Graun, J.J. Rousseau,

Stamitz and Pergolesi

(“Stabat Mater”). In

addition, he managed to have

the most important new

works, that were hitherto

only played for a select

audience at La Pouplinière's

private concerts, given

again for the general public

in the “Concerts

spirituels”. Royer’s only

surviving collection of

“Pièces de clavecin” dates

from 1746, and contains

music of high quality,

marked by subtle harmonies,

melodies conceived mostly

along vocal lines, and great

liveliness.

In 1754, Friedrich Marpurg

reported that Jacques Duphly

had been a pupil of

Dagincourt, and only played

the harpsichord, in order

not to spoil his hands at

the organ. Duphly gave

lessons to the leading

families of Paris, and was

counted among the city’s

best teachers by the

harpsichord-builder Pascal

Taskin. Together with

Balbastre and Armand-Louis

Couperin, however, Duphly

was to be one of the last

major representatives of a

harpsichord tradition going

back some four hundred

years, and he also had to

witness the glorious end of

his instrument. Duphly died

at the age of 84 on 15th

July 1789 - just one day,

symbolically enough, after

the outbreak of the French

revolution. The populace

soon settled the score with

the ancien régime,

its representatives and its

symbols: the aristocratic

harpsichord was literally to

go up in flames, its place

being taken by the rapidly

advancing fortepiano - the

instrument associated with

the bourgeoisie.

Clemens

Romijn

Translation:

Clive Williams

|

|

|

|