|

|

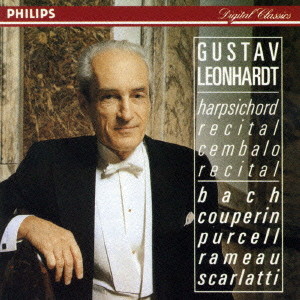

1 CD -

426 352-2 - (p) 1989

|

|

HARPSICHORD

RECITAL

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Louis COUPERIN

(c.1626-1661)

|

Prélude

à l'imitation de Mr. Froberger |

|

6' 59" |

1

|

Henry

PURCELL (1659-1695)

|

Ground

"Crown the Altar" in D minor |

|

2' 01" |

2

|

|

Ground

in C minor - Also

attributed to William Croft

(1678-1727) |

|

3' 05" |

3

|

|

Suite

in D |

|

4' 38" |

4

|

| Johann KUHNAU

(1660-1722) |

Biblische

Sonate "Jacobs Tod und Begräbnis"

|

|

16' 17" |

5 |

| Johann

Sebastian BACH (1685-1750)

|

Aria

- from "Goldberg Variations" BWV 988

|

|

2' 31" |

6

|

|

Kleine

Präludien:

|

|

|

|

|

-

in C BWV 924, in F

BWV 927, in D minor BWV 940,

in G minor BWV 929 |

|

3' 34" |

7

|

|

2

Minuets: |

|

|

|

|

-

in G BWV Anh. 114, in G

minor BWV Anh. 115 - Also

attributed to Christian Pezold

(1677-1733?) |

|

1' 47" |

8

|

|

Präludium

und Fuge E-dur, BWV 878 -

(Wohltemperierte Klavier II, 9) |

|

7' 05" |

9 |

| Domenico SCARLATTI

(1685-1757) |

2

Sonatas in A K. 208 & K.

209

|

|

4' 59" |

10

|

| Joseph-Nicolas-Pancrace

ROYER (c.1705-1755) |

Allemande

in C minor

|

|

3' 21" |

11

|

| Joseph Bodin de

BOISMORTIER (1689-1755) |

La

Puce (Pièce en rondeau) |

|

1'

37"

|

12 |

| Pierre FÉVRIER

(1696-1762/79) |

La

Délectable |

|

4' 02" |

13 |

| Jean-Philippe

RAMEAU (1683-1764) |

Le

Rappel des Oiseaux

|

|

2' 48" |

14 |

|

|

|

|

Gustav

LEONHARDT, Harpsichord (Joel

Katzman, amsterdam 1987)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Haarlem (The

Netherlands) - Settembre 1988

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Artist and

reppertoire production

|

|

Rupert Fäustle

|

|

|

Recording producer |

|

Mike Bremner

|

|

|

Balance &

recording engineer

|

|

Ko Witteveen

|

|

|

Tape editors

|

|

Jan Wesselink | Ko

Witteveen

|

|

|

Art direction

|

|

George Cramer

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Nessuna

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Philips | LC 0305 |

426 352-2 | 1 CD - durata 65'

59" | (p) 1989 | DDD |

|

|

Cover Art

|

|

Photo: Geert Kooiman

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

A

CONCERT OF FOUR NATIONS

This

bird’s-eye view of

harpsichord music from the

mid-seventeenth to the

mid-eighteenth centuries

glances at four countries

and illustrates something of

the diversity of styles

found in that period. The

earliest piece here is that

by Louis Couperin, uncle of

the more famous François but

himself a noted keyboard

player. He was the first to

write improvisatory

“unmeasured” preludes (i.e.

without any indication of

the rhythmic organisation)

for the harpsichord, though

the form had previously been

employed by French lutenists

such as Denis Gaultier. Four

of these freely rhapsodic

preludes of his include a

central rhythmic and

contrapuntal ricercar

- a structure also found in

toccatas by Froberger, who

had become acquainted with

Couperin when he visited

Paris in the 1650’s. Despite

Couperin’s complimentary

title, it is an open

question who in fact

influenced whom.

The chaconne and

passacaglia, both relying on

varied repetitions of a

short melodic or harmonic

phrase, were much favoured

by French composers (and

greatly developed by Lully

in his operas); Purcell in

England, who almost

certainly knew their work,

was a master of the kindred

form of the ground bass,

which he frequently employed

with a new flexibility, the

length of his melodic

phrases masking that of the

pattern in the bass. This

characteristic is seen in

the D minor Ground, which is

a transcription of a

mezzo-soprano solo in the

1693 birthday ode for Queen

Mary, “Celebrate the

festival”: the four-bar

ground appears 13 times,

twice straying from the

basic key to F major and

Aminor respectively. The C

minor piece (probably by

Purcell though once thought

to be by Croft) has twelve

appearances of a ground

lasting three-and-a-half

bars: a quasivocal phrase,

repeated with variants,

alternates with a constant

ritornello. The little Suite

in D - of which the Almand

is the only substantial

movement - is the third of a

set of eight published after

the composer’s death by his

widow.

The “Biblical” Sonatas

composed in 1700 by Kuhnau,

Bach’s predecessor as Kantor

of the Thomaskirche in

Leipzig and a gifted

individual in other fields

besides that of music (he

was a brilliant linguist, an

active lawyer and a

satirical novelist), were

his last keyboard works. He

had been the first to apply

the term “sonata” - without

thereby implying any

specific structural

principle - to music for the

harpsichord alone; but

programmatic sonatas for

other instruments were

already in existence, as for

instance Biber’s “Mystery”

Sonatas for violin and

continuo, 20 years earlier.

Kuhnau’s sixth sonata has

five movements. The grief of

Jacob’s sons, depicted in

slow 4/4 time, is lightened

by his paternal blessing

(three 3/4 passages): they

reflect on the consequences

of his death in a four-part

fugue whose subject rises

sequentially. The lengthy

journey from Egypt to Canaan

to bury him is suggested by

a ceaselessly trudging

quaver bass, and its

weariness by the numerous

right-hand suspensions.

These are also featured in

the following movement, with

a repeated-note figure

imitated between the voices.

The sonata ends in a calmly

flowing triple-time movement

representing the survivors’

feelings of consolation.

Bach’s family all

acknowledged that they owed

their musical education to

him; and much of his

keyboard music was composed

for their benefit and for

his numerous pupils. What

later was taken as the theme

of the “Goldberg” Variations

- itself forming part of his

“Clavier-Übung” (Keyboard

Practice), an instructional

title he had taken over from

Kuhnau - was originally a

sarabande in the 1725

notebook for his wife Anna

Magdalena (which also

contains, written in her

hand, the two little minuets

which may or may not be by

him); three of the small

preludes played here are

from another notebook, five

years earlier in date,

prepared for the tuition of

his eldest son Wilhelm

Friedemann, then aged 9. Of

these, those in C and in F

are for finger fluency and

evenness, that in G minor is

a minuet. BWV 940 in D

minor, from a different set

of five preludes written at

about the same time, is an

exercise in part-playing.

The E major Prelude from the

second book of the

“Welltempered Clavier” is

also contrapuntal but in

binary form, like a movement

from a suite: the grave

four-part Fugue has as

subject a mere conventional

tag, but this is treated in

various forms of stretto.

Though born in Naples of a

Sicilian family, Domenico

Scarlatti spent the latter,

and more productive, half of

his life in the Iberian

peninsula. As music master

to the Infanta Maria

Barbara, later queen of

Spain, he there wrote the

over 500 keyboard sonatas,

of infinite vitality and

variety, on which his fame

rests. Some of these were

apparently designed to be

played in pairs: one such

pair comprises the present

two A major pieces, the

first with a florid melodic

line over a firm marching

step, the second a bright,

springy jota.

The remaining pieces are all

by French clavecinistes

active in Paris. The

dramatic Allemande by Royer

(music master to Louis XV’s

children, and later director

of the Concert Spirituel)

displays his fondness for

taut dotted rhythms and for

rushing tirades

(sweeping scale upbeats);

“La puce” by Boismortier,

his senior by some 20 years,

is a rondeau which

graphically and amusingly

illustrates its title; “La

délectable” by Février

(organist at the

Sainte-Chapelle and the

Jacobin convent) is a

stately, gracious,

richtextured character piece

in binary form; and Rameau’s

“Rappel des oiseaux” is

delicately programmatic,

with repeated bird-calls,

twitterings and suggestions

of fluttering wings.

©

1989 Lionel Salter

|

|

|

|