|

|

1 CD -

432 128-2 - (p) 1991

|

|

WORKS FOR

HARPSICHORD

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Girolamo

FRESCOBALDI (1583-1643) |

Toccata

Decima (1615) |

|

3' 54" |

1 |

|

Toccata

undecima (1615)

|

|

4' 49" |

2

|

|

Recercar

nono, con quattro soggetti

(1615)

|

|

4' 20" |

3

|

|

Canzona

quarta (1627)

|

|

2' 45" |

4

|

|

Canzona

terza, detta la Crivelli

(1645)

|

|

2' 50" |

5 |

|

Partite

sopra Folia (1615)

|

|

5' 38" |

6 |

|

Capriccio

di durezze (1624)

|

|

3' 24" |

7 |

|

Toccata

settima (1615)

|

|

4' 39" |

8 |

|

Capriccio

sopra un soggetto (1624)

|

|

5' 18" |

9

|

|

Fantasia

terza, sopra un soggetto solo

(1608)

|

|

4' 19" |

10 |

|

Toccata

seconda (1627)

|

|

3' 02" |

11

|

|

Balletto

I, corrente e passacagli (1637)

|

|

1' 44" |

12 |

|

Balletto

II e corrente (1637) |

|

1' 08" |

13 |

|

Fantasia

nona, sopra tre soggetti

(1608)

|

|

5' 37" |

14

|

|

Toccata

decima (1627) |

|

3' 54" |

15

|

|

|

|

|

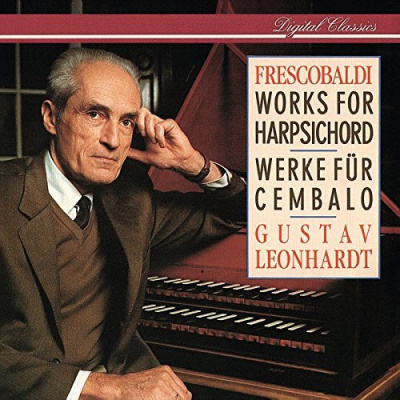

Gustav

LEONHARDT, Harpsichord (Cornelis

and Hubrecht Bom, 1987)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Doopsgezinde Kerk,

Haarlem (The Netherlands) -

Settembre 1990

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Artist and

reppertoire production

|

|

Wouter Hoekstra

|

|

|

Recording producer,

balance engineer

|

|

Hein Dekker

|

|

|

Recording

engineer

|

|

Fiona Gale

|

|

|

Tape editors

|

|

Fiona Gale | Arnoud

Probst

|

|

|

Art direction

|

|

George Cramer

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Nessuna

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Philips | LC 0305 |

432 128-2 | 1 CD - durata 58'

12" | (p) 1991 | DDD |

|

|

Cover Art

|

|

Photo: Geert Kooiman

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

LINKING

RENAISSANCE AND BAROQUE

Frescobaldi

was born into a fairly

wellto-do family in Ferrara,

but his general education

seems to have been sketchy.

One contemporary classed him

among those who are "so

ignorant in letters that

they scarcely know how to

write their own names" (and

certainly those writings of

his that have survived are

full of idiosyncratic

spelling and syntax); and

another, who called him "a

very common man," accused

him not merely of faulty

wordsetting in his vocal

music but of not even

understanding any unusual

words. It was a very

different matter when it

came to his talens as a

performer, which commanded

universal admiration. He was

called "the prodigy of his

time": one musician wrote

that "for organ and cembalo

he carries off all the

honours, both in his skill

and in the agility of his

hands," and another

commented that he had "found

a new style of playing,

especially on the

harpsichord," adding that

"today anyone not playing in

this style is hardly to be

considered." As a composer,

Frescobaldi exercised great

influence, especially

through his pupil Froberger

(who left his post at the

Imperial court in Vienna for

over three years in order to

study with him): J.S. Bach

as a young man attempted to

copy his style.

Frescobaldi's importance lay

particularly in his

development of keyboard

music, in which sphere his

contribution was equalled at

the time only by Sweelinck

in Amsterdam and John Bull

in London and Antwerp: he

represents a link between

the contrapuntal disciplines

of the late Renaissance and

the freer, more decorative

flights of the Baroque,

often with bold usage of

dissonance (in which he was

influenced by Gesualdo, who

had spent some time in

Ferrara, and by other

Neapolitan composers), and

in particular displaying a

talent for improvisatory

figurations and for

variation technique (of

which Cabezón had been the

father-figure). He also gave

unusually precise and

practical directions for the

performance of his works:

players were encouraged to

"discover the right

affective expression of each

passage" and to feel free to

alter speeds within a piece

as the character of the

music changed (as was the

custom in contemporary

madrigal singing), to begin

toccatas slowly so as to

increase the brilliance of

later, faster sections, to

slow down towards cadences

and make pauses between

sections.

Frescobaldi's first

publication for keyboard, in

1608, consisted of 12

Fantasias: though printed in

score, each voice line on a

separate stave, they are

entirely apt for keyboard

performance. The most

intellectual of his works,

each fantasia strictly

derives the whole of its

contrapuntal texture from

the initial soggetto

or soggetti (melodic

figures rather than

"subjects" in the modern

sense), which vary in number

from one to four. In

Fantasia III (which changes

for a while to triple metre

halfway through) the

contours of the single soggetto

- a rising second, a rising

fourth and fives notes of an

ascending scale - are

clearly recognisable

throughout: the three soggetti

of Fantasia IX - one

ascending, another

descending, the third

circling round one note -

are all presented at the

beginning, the first

eventually engendering a

figure of rising semitones.

In contrast, normally in

ricercari the soggetti

were deployed in successive

sections, but Ricercar IX

from Frescobaldi's 1615

collection is exceptional in

developing all four of its

themes simultaneously - a

remarkable contrapuntal feat

which has been called a

distant forerunner of Bach's

uncompleted Contrapunctus XV

in "Die Kunst der Fuge."

In 1615 also appeared the

First Book of Toccatas, an

immensely popular volume

that was reprinted several

times (with revisions and

additions). The toccatas

represent a transition from

the traditional modes (No. 7

is basically in the Aeolian,

Nos. 10 and 11 are in the

Ionian) to the new system of

tonality, bringing in its

train a shift from linear to

harmonic thinking (No. 11 is

strikingly free in this

regard, employing many

chromaticisms). More

importantly, to an

extraordinary degree they

mirror Frescobaldi's

acclaimed art of

improvisation - full of

brilliant passaggi

and ornamental cadences, the

chordal framework

embellished with decorative

flights passed from one

voice to another, and with

an unmistakable expressive

quality. His relative

indifference to the

structure of the whole is

shown by his remark, in the

second edition, that each

section "may be played on

its own apart from the

others, so that the

performer is not obliged to

finish the whole work but

may stop where he desires."

The same volume also

contains a few partite

(sets of variations) on

popular melodies. That

adopted for "La Folia,"

however, is not the familiar

theme used by Corelli and

others, but a binary one

usually called the fedele.

1624 saw the publication of

a book of 12 capricci

which also enjoyed a wide

popularity. although all

employ an abundance of

imitative counterpoint, they

cover a variety of

treatments. The majority are

multisectional pieced based

on such familiar subjects as

ascending or descending

hexachords, the cuckoo's

call or traditional dance

tunes from the Low

Countries, but one is a

riddle for a fifth singing

part - the entry points left

to the performer's ingenuity

- to be added to the

four-part instrumental

composition. The "Capriccio

sopra un soggetto" displays

Frescobaldi's mastery pf

variation technique, the

rhythmically energetic soggetto

itself becoming modified (as

in the canzona form) in the

successive variations of

pace, metre and figuration.

On the other hand, the

shorter "Capriccio di

durezze" (on dissonances) is

more akin to a ricercare: it

is a structurally continuous

whole with well defined,

well developed motifs but

without passaggi or

metrical changes: its

chromaticism lends it great

expressiveness.

The second Book of Toccatas

of 1627 in fact contains,

besides 11 toccatas (some

specifically designated for

organ), a great diversity of

other forms, including

canzonas, liturgical

movements, variations and

dance pieces. Frescobaldi

announced it as exemplifying

a "new manner... with

novelty of artifice" and

calling for "grace, ease,

variety of measure, and

elegance" in performance.

Certainly the complexity of

the texture is greater than

in the First Book, with

elaborate passage-work,

sequences, more pronounced

contrasts between the

various sections, and

lenghty preparation of

cadences. No. 10 is

especially notable for the

variety of its rhythmic

patterns, which include

Lombard snaps and dotted

figures. The spirited

Canzona No. 4 from this book

falls into several sections

(the first a short fugue)

strongly differentiated in

metre and rhythm, though

unity is preserved by all

the material being derived

from that in the initial

part.

In the third edition (1637)

of his First Book of

Toccatas, Frescobaldi added

several extra pieces, among

them some miniature dance

groups. In both the first

and second of these there

are two binary movements - a

balletto in duple

metre and a triple-metre corrente

which is thematically

related (more obviously in

No. 1); but No. 1 concludes

with a passacagli

(consisting of six

appearances of the twobar

ground bass). Two years

after Frescobaldi's death,

11 canzoni alla francese

were brought out by the

Venetian publisher

alessandro Vincenti. The

title "La Crivelli," the

third of these, almost

certainly refers to Giovanni

Battista Crivelli, who some

time in the 1620's was maestro

di cappella in

Frescobaldi's native town of

Ferrara: it is in effect a

fugue in firmly regular

duple rhythm.

©

1991 Lionel Salter

|

|

|

|