|

|

1 CD -

432 968-2 - (p) 1992

|

|

LES PALADINS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Jean-Philippe

RAMEAU (1683-1764) |

Les

Paladins - Suite |

|

39' 09" |

|

|

-

Ouverturetrès vite

|

3' 37" |

|

1

|

|

-

Menuet lent |

1' 41" |

|

2

|

|

-

Air gay

|

1' 56" |

|

3

|

|

-

Entrée des Pèlerins

|

4' 01" |

|

4 |

|

-

Loure

|

3' 10" |

|

5 |

|

- Pantomime |

2' 28" |

|

6 |

|

- Air de

furie |

2' 08" |

|

7 |

|

-

Sarabande

|

3' 11" |

|

8

|

|

-

Menuet en rondeau

I-II |

5' 40" |

|

9 |

|

-

Entrée très gaye des Troubadours

|

2' 40" |

|

10

|

|

- Air très gay |

1' 47" |

|

11 |

|

-

Gavotte

|

0' 31" |

|

12 |

|

-

Menuet

|

0' 56"

|

|

13

|

|

-

Contredanse (en rondeau)

|

1' 12" |

|

14

|

|

-

Entrée des Chinois

|

2' 32" |

|

15 |

|

-

Loure |

3' 31" |

|

16 |

|

-

Gigue vive

|

3' 24" |

|

17 |

|

-

Air vif |

1' 42" |

|

18 |

|

-

Première gavotte gaye - deuxième

gavotte

|

2' 39" |

|

19 |

|

-

Air très gay |

4' 22" |

|

20 |

|

-

Entrée des Paladines et ensuite

Paladins

|

3' 11" |

|

21 |

|

-

Air pour les Pagodes |

3' 06" |

|

22 |

|

-

Gavotte I-II

|

2' 12" |

|

23 |

|

-

Contredanse en rondeau |

1' 51" |

|

24 |

|

|

|

|

|

ORCHESTRA OF THE AGE

OF ENLIGHTENMENT on period instruments

- Elizabeth Wallfisch, Alison Bury,

Peter Lissauer, Catherine Ford, Susan

Carpenter-Jacobs, Violins 1

- Catherine Mackintosh, Catherine Weiss,

Marshall Marcus, Desmond Heath, Violins

2

- Jan Schlapp, Annette Isserlis, Marti

Kelly, Violas

- Susan Sheppard, Timothy Mason, Violoncelli

- Amanda Macnamara, Double-bass

- Lisa Beznosiuk, Stephen Preston, Flutes

- Anthony Robson, Richard Earle, Oboes

- Andrew Watts, Felix Warnock, Bassoons

- Susan Dent, Colin Horton, Horns

- Paul Nicholson, Harpsichord

Gustav LEONHARDT, Direction |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

St. Giles,

Cripplegate, London (England) -

Gennaio 1991

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Artist and

reppertoire production

|

|

Wouter Hoekstra

|

|

|

Recording producer

|

|

Martha de Francisco

|

|

|

Balance engineer |

|

Martha de Francisco

|

|

|

Balance,

recording engineer

|

|

Andreas Neubronner

|

|

|

Tape editors

|

|

Kees de Visser |

Martha de Francisco |

|

|

Art direction

|

|

George Cramer

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Nessuna

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Philips | LC 0305 |

432 968-2 | 1 CD - durata 63'

45" | (p) 1992 | DDD |

|

|

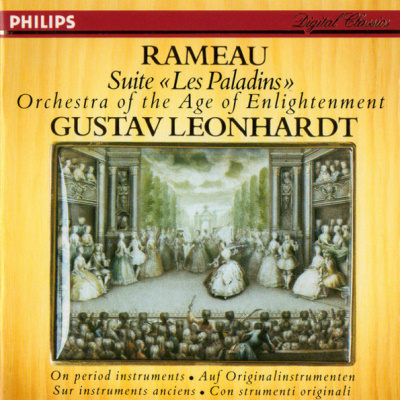

Cover Art

|

|

"Scène de ballet ou

représentation théâtrale".

Miniature on the lif of a snuffbox

(18th century) by M.J. van

Blarenberghe. Visual Arts Library

/ Musée du Louvre, Paris (1992).

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Jean Philippe

Rameau’s comédie lyrique

“Les Paladins” was given its

premiere at the Académie

royale de musique (the

predecessor of the Paris

Opéra) in February and March

of 1760. It was Rameau’s

first music drama of more

than one act since “Acanthe

et Céphise” in 1751; hence

it was anticipated with

great interest. By all

accounts, the opera was

given the lavish production

to be expected for a work by

the acknowledged greatest

living French composer. The

success of the new opera,

however, did not live up to

anticipation: only five of

the first seven performances

produced receipts exceeding

those of a new production of

Lully’s “Amadis de Gaule”

mounted around the same

time, and the production

closed after just 15

performances, never to be

heard again until a 1967

revival in Lyons. That

modern revival elicited the

appreciative description

from one reviewer of a

“score in which the aged

Rameau gave us quite simply

his ‘Falstaff’.”

Contemporary reviews of the

première production of “Les

Paladins” focused their

criticism on the perceived

deficiencies of the

anonymous libretto.

Undoubtedly, some of the

negative response to the

work resulted from its being

one of only a very small

number of comic works to

have appeared at the Opéra;

as such it adhered to

different dramatic

conventions than the more

traditional genres, the tragédie

lyrique, the opéra-ballet,

and the pastorale-héroïque.

In truth, comparison of the

work’s libretto with stage comédies

of Molière and Marivaux

permits the conclusion that

Rameau’s librettist was

indeed not in the league of

either of these principal

representatives of French

comic traditions.

Composition of “Les

Paladins” apparently

occupied Rameau for longer

than was usual for him. An

anonymous letter dated 7

August 1756, to a

correspondent at the

Palatine court in Mannheim,

informs us that Rameau “has

written the music for an opera

bouffon.”

Recent examination of

Rameau’s composing score for

“Les Paladins” has allowed

us to infer that the

original composition of the

opera was likely

contemporaneous with his

revision during 1757 of the

opéra-ballet “Les

surprises de l’amour.” In

addition, there are many

significant changes in

instrumentation between this

composing score and the one

used for the production of

1760 - changes which seem

primarily to have been

motivated by the appearance

in 1759 in the Opéra

orchestra of proficient horn

players. The most

significant difference in

the two scores is in the ouvertures;

that in the production score

is scored with two horn

parts, and is in a key more

appropriate to the horn than

is the ouverture of

the composing score. In all,

eight numbers in addition to

the ouverture have horn

parts added in Rameau’s hand

in the production score.

During the 1750’s, much of

Paris society was taken up

with the so-called guerre

des bouffons, a

pamphlet war in which the

relative merits of Italian

and French opera were

debated by contemporary literati.

A spate of new theoretical

writings by Rameau indicates

that he too was at least

somewhat preoccupied with

the issues raised by the

aesthetic dispute. Indeed,

Rameau is quoted by Grétry

as having said that were he

35 years younger he would go

to Italy, where Pergolesi

would be his model, but that

at the age of “over 60 one

must stay where one is.” In

some of the one-act ballets

written during this period

for Fontainebleau, as well

as in some of his revisions

of earlier works, Rameau can

be observed to experiment

occasionally with the more galant

Italian style of Pergolesi.

In “Les Paladins,” however,

the experimentation is more

overt: in one air, for

example, he instructs the

player of the obbligato oboe

to play “un peu gai à la

française [i.e., with notes

inégales?].” This

number is immediately

followed by a duo which a

contemporary copyist

understood to be so

representative of the

Italian style that he

entitled it in a manuscript

of around 1770 “Duo amoroso”!

Other elements of the vocal

music, especially in lyric

dialogue scenes, suggest an

attempt to incorporate the

new style of the opera

buffa into a French

setting, and the appearance

of full-blown da capo

arias within the stream of

the dramatic action - even

if they are still given the

French designation ariette

- is also a reflection of

Pergolesi’s practice.

If Rameau’s contemporaries

were uneasy with the

non-traditional aspects of

“Les Paladins,” they

nonetheless often expressed

appreciation of the opera’s

instrumental music. Writing

in “Mercure,” the leading

Parisian periodical of arts

and letters, one

contemporary reviewer wrote:

As

to the music, it

everywhere bears the stamp

of its illustrious

composer. As is generally

the case with his music,

it has been better

expressed with each

performance. Justice is

done to the beauty, the

very novelty, of the

symphonies [i.e., the

instrumental movements].

The overture has been

loudly applauded.

Respect

for Rameau’s instrumental

writing is evident in the

fact that at least one dance

movement, the “Entrée très

gaye de Troubadours” of Act

II, scene 10, appears in a

manuscript pastiche dating

from some 15-20 years after

Rameau’s death.

Despite its experimental

tendencies, “Les Paladins”

caters to the French taste

of the ancien régime

with a divertissement

of chorus and dance music in

each act. Whereas in some of

Rameau’s earlier tragédies

a case could be made that

the divertissements

are non-essential to the

drama - indeed they often

inhibit its forward progress

- in “Les Paladins,” the divertissements

are at the least strongly

motivated by the dramatic

action, and one, the

sequence of danses

d’action and danced

choruses of Act I, scene 6,

is crucial in establishing

the less than heroic

qualities of one of the

opera’s two principal comic

figures.

The third-act divertissement

is somewhat more decorative,

celebrating the future

happiness of the two young

lovers whom the audience has

seen overcome obstacles

posed by the young lady’s

fatuous elderly guardian, a

Venetian senator named

Anselme. Rameau and his

librettist take full

advantage of the opportunity

presented by their model -

La Fontaine’s tale “Le petit

chien qui secouë de l’argent

et des pierreries,” which

had in turn been derived

from Canto XLIII of Ludovico

Ariosto’s “Orlando furioso” - to

introduce elements of

romantic fantasy into the

work at this point. At the

opera’s denouement, just as

Anselme and his troops are

storming his own chateau -

where the two lovers have

holed up - the chateau

suddenly disappears through

the agency of a friendly

fairy, and a marvellous

Chinese palace and garden

appear in its stead. Not

only is evil thwarted, but

there is now an excuse for a

sensuous “Air pour les

Pagodes,” during which the

Chinese dolls which inhabit

the enchanted garden

“begin,” according to the

stage directions, “to move

their heads, come slowly to

life, and leave their places

to render [mock] homage to

Anselme, dancing about him

in comic postures.” The

“Entrée de Chinois" which

appears later in the act,

during the pre-nuptial

gaiety, further caters to

the French love of chinoiserie.

However experimental “Les

Paladins” may be as a

dramatic work, no one

familiar with the

instrumental music of

Rameau’s earlier works would

fail to recognise his stamp

here. Rameau’s mastery of

colourful instrumentation is

everywhere apparent - from

the punctuating triple stops

of the two solo violins in

the third movement of the

overture to the explicit

instructions for subtle

breathing and bowing in the

“Entrée de Pélerins” ofAct

I. In sum, it is difficult

to disagree with the ardent

late eighteenth-century

Rameauphile, J.J.M. Decroix

when he writes that the

music of “Les Paladins” was

so full of fire and

imagination that it seemed

to be composed by an artist

in the prime of life rather

than by an old man of 80

[sic].”

©

1991 R. Peter Wolf

|

|

|

|