|

|

1 CD -

438 153-2 - (p) 1993

|

|

FANTASIAS,

PAVANS & GALLIARDS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| William

BYRD (1543-1623) |

Pavan

"Ph. Tregian" & Galliard |

Harpsichord |

|

7' 16" |

1 |

|

My

Lady Nevell's Ground

|

Harpsichord |

|

5' 14" |

2

|

| Robert

JOHNSON (c.1583-1633) |

Alman |

Harpsichord |

|

0' 47" |

3

|

| Peter PHILIPS

(1560/1-1628) |

Passamezzo

Pavana & Galiarda Passamezzo

|

Harpsichord |

|

13' 12" |

4

|

| Thomas MORLEY

(1557/8-1602) |

Fantasia |

Harpsichord |

|

5' 31" |

5 |

| John BULL

(?1562/3-1628) |

Duchess of

Brunswick's Toy |

Virginal |

|

1' 02" |

6 |

|

Duke of

Brunswick's Alman

|

Virginal |

|

1' 48" |

7 |

|

John Lumley's

Pavan & Galliard |

Harpsichord |

|

6' 44" |

8 |

|

Fantasia

|

Harpsichord |

|

2' 32" |

9 |

| William RANDALL

(b. ?1604) |

Galliard

"Can she excuse my wrongs?" -

(John Dowland) |

Harpsichord |

|

2' 30" |

10

|

| Giles FARNABY

(c.1563-1640) |

A Toye |

Harpsichord |

|

1' 17" |

11 |

|

Orlando GIBBONS

(1583-1625)

|

Fantasia |

Harpsichord |

|

1' 09" |

12

|

| Thomas TOMKINS

(1572-1656) |

Pavan

& Galliard of 3 parts |

Harpsichord |

|

3' 06" |

13 |

| Orlando GIBBONS

|

Fantasia

|

Harpsichord |

|

3' 15" |

14 |

| Giles FARNABY |

Fantasia

|

Harpsichord |

|

3' 41" |

15

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gustav

LEONHARDT, Harpsichord &

Virginal

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Evangelisch-Lutherse

Kerk, Haarlem (The Netherlands) -

Ottobre 1992

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Artist and

reppertoire production

|

|

Stef Collignon

|

|

|

Recording

producer |

|

Hein Dekker

|

|

|

Balance

engineer

|

|

Hein Dekker

|

|

|

Recording

engineer

|

|

Jean-Marie Geijsen

|

|

|

Tape editor

|

|

Hans Meijer

|

|

|

Art direction

|

|

George Cramer

|

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Nessuna

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Philips | LC 0305 |

438 153-2 | 1 CD - durata 59'

47" | (p) 1993 | DDD |

|

|

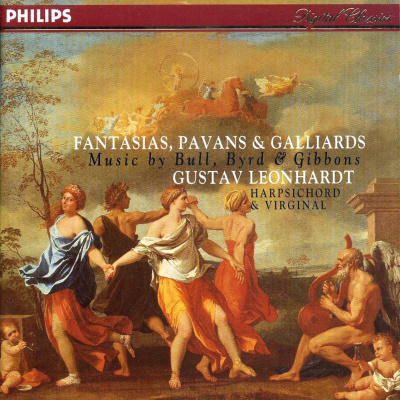

Cover Art

|

|

"Il Ballo della Vita

humana", painting by Nicolas

Poussin (1594-1665), Wallace

Collection, London.

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

UNDERCURRENTS

IN ELIZABETHAN VIRGINALS

MUSIC

In

the development of keyboard

music in the sixteenth

century, England played a

decisive role. Cabezón in

Spain and Sweelinck in The

Netherlands were both making

important contributions, but

England produced a whole

host of composers for the

keyboard, more specifically

(unlike their foreign

contemporaries) for the

harpsichord or virginals

rather than the organ, and

predominantly secular, not

liturgical. There were

transcriptions of popular

tunes of the day, and sets

of variations (sometimes

very extensive and

elaborate) on them; madrigal

arrangements; small

character pieces;

contrapuntal fantasies or

“fancies” akin to the

ricercare; and dance

movements, chief of which

were pavanes and galliards.

These two, paired and

sometimes thematically

connected, were thus

described by Morley: [the

pavan is] “a kind of staide

musicke, ordained for grave

dauncing, and most commonlie

made of three straines,

whereof everie straine is

plaid twice... After every

pavan we usually set a

galliard (a kind of musicke

made out of the other)... a

lighter and more stirring

kinde of dauncing." A number

of valuable collections of

keyboard music are known,

the most important being the

Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, a

volume of almost 300 pieces

in the hand of Francis

Tregian the younger, a

Cornish Catholic who was

detained in the Fleet Prison

for his religious beliefs

from 1609 until his death

ten years later: he spent

his time copying existing

pieces - mostly by fellow

recusants, exiles and

friends. His book eventually

passed to Richard, Viscount

Fitzwilliam, and thence to

the Cambridge museum that

bears his name. Another

volume, My Ladye Nevells

Booke, contains over

40 pieces by Byrd, who lived

only a few miles from the

home of Sir Edward Nevill

(later Lord Bergavenny) and

his wife Rachel.

Tregian and Lady Nevill are

commemorated in the items by

Byrd which begin the present

programme. William Byrd, who

at the age of 20 became

organist of Lincoln

cathedral and a decade later

of the Chapel Royal, was

held in the highest

admiration by his

contemporaries (Morley said

that he “was never without

reverence to be named”), and

such was his reputation that

a blind eye was turned to

his Roman Catholicism. His

large output included both

Masses and Anglican

services, motets and

anthems, vocal collections,

music for viols, and well

over 100 keyboard pieces.

There is no thematic link

between the pair of dances

inscribed to Tregian, [1]

and the galliard is

altogether simpler in style

than the pavan, in the

repeats of whose sections

there is much imitation

between the voices. In the

brilliant piece for Lady

Nevill [2], which appears to

date from 1590, there are

six variations on the

ground, which is itself

complex, consisting of eight

iterations of a two-bar cell

(four in D and four in G)

followed by a four-bar cell

played twice. In the fifth

variation there is a change

of rhythm, and the final

variation ends in a flurry

of semiquavers.

By far the most flamboyant

of the writers for

virginals, and its most

virtuosic player, was John

Bull. After a few years as

organist of Hereford

Cathedral (to which he too

had been appointed when only

20) he joined Byrd, his

senior by 20 years, as an

organist at the Chapel

Royal, where as a boy he had

been chorister. He was

greatly favoured both by

Queen Elizabeth and by James

I, to whose children he was

musical tutor, but at the

age of 50 he fled the

country. ostensibly for

religious reasons (he had

become a Roman Catholic) but

more urgently to escape

punishment on charges of

flagrant immorality; he

spent the rest of his days

in voluntary exile in

Brussels and Antwerp, where

he became cathedral

organist. In l60l he had

spent a pleasant time at the

court of Brunswick, where

the young duke and his

consort were enthusiastic

musical amateurs, and Bull‘s

tributes to his hosts

[6]-[7] (that to the duchess

has the superscription “Most

sweet and fair") are both

simple pieces presumably

intended for them to ay. On

the other hand, the pavan

for Lord Lumley [8], with

its volatile scalic runs,

gives some indication of

Bull’s extrovert virtuosity

(though its melodic charm

should not be overlooked);

and it also shows his

disregard for conventional

phrase lengths, since

although its third strain is

of the usual eight bars, the

first and second strains are

each of 11. The constant

canonic interplay in the

thematically independent

galliard illustrates his

contrapuntal ingenuity, for

which he was famous. The

dedication is also

significant, for John, the

first Baron Lumley, a

favourite of Mary, Queen of

Scots, was imprisoned for

four years for his

involvement in the Ridolfi

plot to overthrow Elizabeth’

government. The short

Fantasia [9] is entirely

constructed on the initial

five-bar figure.

Another Roman Catholic who

went into voluntary exile

because of his religion, and

later even took holy orders,

was Peter Philips, who had

been a fellow student with

Francis Tregian at the

Jesuit seminary in Douai,

and who was briefly

imprisoned for his

implication in a conspiracy

to assassinate Elizabeth but

released for lack of

evidence. He then went to

Antwerp and Brussels in the

service of the Archduke

Albert, where he was later

joined by John Bull. He was

very highly regarded as a

musician, though his erudite

Italianate style met with

some criticism. The

passamezzo [4]

(Shakespeare's

“passy-measures") was one of

a number of common chord

sequences used as grounds

upon which variations were

written for a faster version

of the pavan. The example by

Philips, in which the

lengthy ground occurs seven

times, is densely

contrapuntal in texture and

technically extremely

demanding on the player: in

the sixth variation the

rhythm changes to a triple

sub-beat. The galliard, on

the same ground, is rather

less complex, but the last

two of its ten variations

are headed “Saltarella."

Bearing in mind the

politico-religious

undercurrents of the time,

the words of Dowland's ayre

Can she excuse my wrongs

set by William Randall [10],

an organist and lay clerk in

the Chapel Royal and at

Exeter Cathedral - which

Dowland himself arranged for

viols as The Earl of

Essex Galliard - are

particularly significant.

Though connected with the

queen's rebellious favourite

Robert Devereux, they were

also applicable to Dowland’s

own case. At the age of 20

he had become a Roman

Catholic and found his

religion a bar to

advancement; after staying

with the Duke of Brunswick

he had fallen in with a

number of English recusants

on the Continent, but took

alarm at their treasonable

plots, which he denounced to

Elizabeth's secretary of

state Sir Robert Cecil, with

a view to regaining favour

at home. Randall, like

Dowland, treats the song as

a galliard, with each strain

followed by a decorated

repeat: the third strain

follows the original in

quoting the very popular

folk song The woods so

wild.

Like Dowland, Thomas Morley,

a pupil of Byrd's, had a

hand in political intrigue.

After moving from Norwich

Cathedral to St Paul’s as

organist, he seems to have

been employed as an informer

in the Low Countries, and

though ostensibly a Roman

Catholic sent a letter to

the Dean of St Paul's

warning him of the sedition

planned by recusants there.

Though chiefly noted for his

canzonets and madrigals, his

keyboard music, as in the

present clearly structured

Fantasia, shows considerable

fluency.

Two of the composers

represented here, both

Anglicans, probably owe

their inclusion in Tregian‘s

anthology to their Cornish

ancestry. Giles Farnaby, a

joiner and keyboard

instrument builder, is

chiefly remembered for his

charming miniatures, like

his Toye [11] in two

strains, each repeated with

a variant) and the

transcription of an Alman by

James I’s lutenist Robert

Johnson (who wrote music for

many plays, including works

by Shakespeare, Webster and

Ben Jonson). In large forms

he is less at ease, with

awkward key shifts, but the

present Fantasia [15] also

contains some surprising

chromaticisms and an

allusion to Dowland‘s Lachrymae.

Thomas Tomkins, one of the

last virginalists, also came

of Cornish stock. A pupil of

Byrd’s, he spent his life as

organist of Worcester

Cathedral, although he also

held a titular appointment

to the Chapel Royal. Besides

music of his own, much of it

deeply expressive, he

assembled a collection

(published posthumously) of

works for the Anglican

church. His Pavan and

Galliard of Three Parts

[13] breaks with the normal

tradition not only by not

providing decorated repeats

of the strains but, more

fundamentally, by the pavan

being in triple time.

A colleague of Tomkins at

the Chapel Royal was his

junior by 11 years, Orlando

Gibbons, who became organist

there at the age of 21 and

later moved to Westminster

Abbey. He was widely praised

as the most brilliant

musician of his generation,

and as a player “the best

hand in England." The exact

reverse of Farnaby, he

excelled in extended works

and the opening of his

magnificent Fantasia in C

[14] reveals his ability to

build small thematic cells

into mounting expressive

phrases.

©

1993 Lionel Salter

|

|

|

|