|

|

1 CD -

442 119-2 - (p) 1994

|

|

CANTATAS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann

Sebastian BACH (1685-1750) |

KOMMT,

EILET UND LAUFET, BWV 249 - Easter

Oratorio

|

|

43' 41" |

|

|

-

Sinfonia

|

4' 08" |

|

1

|

|

- Adagio

|

4' 12" |

|

2

|

|

-

Choir und Duet (Tenor, Bass):

"Kommt, eilet und laufet"

|

5' 35" |

|

3

|

|

-

Recitativo (Alto, Soprano, Tenor,

Bass): "O kalter Männer Sinn!"

|

0' 54" |

|

4 |

|

- Aria (Soprano):

"Seele, deine Spezerein"

|

10' 50" |

|

5 |

|

- Recitativo

(Tenor, Bass, Alto): "Hier ist die

Gruft"

|

0' 40" |

|

6 |

|

- Aria (Tenor):

"Sanfte soll mein todeskummer" |

7' 25" |

|

7 |

|

-

Recitativo and Arioso

(Soprano, Alto): "Indessen

seufzen wir mit brennender

Begier" |

0' 53" |

|

8 |

|

- Aria (Alto):

"Saget, saget mir geschwinde" |

5' 50" |

|

9

|

|

- Recitativo

(Bass): "Wir sind erfreut" |

0' 37" |

|

10 |

|

- Choir and

Allegro: "Preis und Dank"

|

2' 23" |

|

11

|

|

LOBET

GOTT IN SEINEN REICHEN, BWV 11 -

Ascension Oratorio |

|

29' 30" |

|

|

-

Choir: "Lobet Gott in seinen Reichen"

|

5' 19" |

|

12 |

|

-

Recitativo (Tenor): "Der Herr Jesus

hub seine Hände auf" |

0' 29"

|

|

13

|

|

-

Recitativo (Bass): "Ach, Jesu, ist

dein Abschied schon so nah?" |

1' 04" |

|

14 |

|

-

Aria (Alto): "Ach, bleibe doch, mein

Liebstes Leben" |

6' 56" |

|

15 |

|

-

Recitativo (Tenor): "Und ward

aufgehoben yusehends" |

0' 24" |

|

16 |

|

-

Choral: "Nun lieget alles unter dir"

(Choral) |

1' 03" |

|

17 |

|

-

Recitativo (Tenor, Bass): "Und da

sie ihm nachsahen gen Himmel fahren" |

1' 01" |

|

18 |

|

-

Recitativo (Alto): "Ach, ja! So

komme bald zurück" |

0' 35" |

|

19 |

|

-

Recitativo (Tenor): "Sie aber

beteten ihn an" |

0' 38" |

|

20 |

|

-

Aria (Soprano): "Jesus, deine

Gnadenblicke" |

6' 58" |

|

21 |

|

-

Choral: "Wenn soll es doch

geschehen" |

4' 48" |

|

22 |

|

|

|

|

Monika

Frimmer, Soprano

Ralf Popken, Alto

Christoph Prégardien, Tenor

David Wilson-Johnson, Bass |

ORCHESTRA AND CHOIR

OF THE AGE OF ENLIGHTENMENT

Elizabeth Wallfisch, Violin

Lisa Beznosiuk, Flute

Anthony Robson, Oboe and Oboe

d'amore

Susan Sheppard, Cello

Nicholas Parle, Organ

Gustav LEONHARDT, Direction |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

St. Giles

Cripplegate, London (England) -

Aprile 1993

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Artist and

reppertoire production

|

|

Stef Collignon

|

|

|

Recording producer |

|

Martha de Francisco

|

|

|

Balance engineer

|

|

Ko Witteveen

|

|

|

Recording

engineer

|

|

Jan Wesselink

|

|

|

Tape editor

|

|

Jean van Vugt |

Martha de Francisco

|

|

|

Art direction

|

|

George Cramer

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Nessuna

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Philips | LC 0305 |

442 119-2 | 1 CD - durata 73'

23" | (p) 1994 | DDD |

|

|

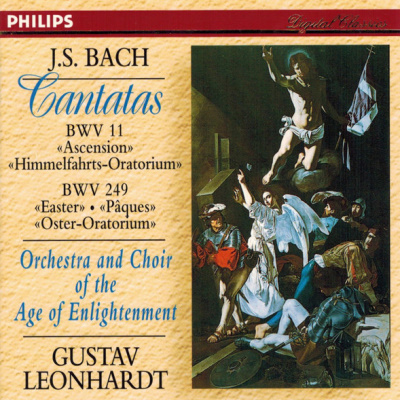

Cover Art

|

|

"Resurrection" by

Caravaggio (1573-1610).

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

BACH:

EASTER AND ASCENSION

ORATORIOS

Easter

Oratorio, BWV 249

It is surprising that a work

whose music possesses such

immediacy of appeal is so

seldom performed. Bach’s

Easter Oratorio, however,

has a complicated pedigree.

In February 1725 the

composer produced a secular

cantata, “Entfliehet,

verschwindet,” BWV 249a, for

the birthday of Duke

Christian of

Saxe-Weissenfels - he whom

Bach had previously honoured

in 1713 with another

birthday treat, the

so-called “Hunting” Cantata

(BWV 208). Then, in April of

the same year, Bach and his

librettist, Picander,

parodied the earlier

birthday cantata, rewrote

the recitatives and perhaps

made other small

adjustments, too. In this

form, and now dressed in

sacred clothes the work was

performed in Leipzig on

Easter Day, 1725. That

version has not survived,

but in 1726 Bach revived the

piece again, this time as a

birthday offering to Count

Joachim von Flemming

(1665-1740) and with a

revised text “Verjaget,

zerstreuet,” BWV 249b. The

Count was the Elector’s

military governor of Leipzig

for whom Bach later composed

two further cantatas, “So

kämpfet nur, ihr muntern

Töne," BWV Anh. 10, and “O

angenehme Melodei,” BWV

210a. It has also been

suggested that Bach

performed his poignantly

expressive motet, “O Jesu

Christ, mein Lebens Licht,”

BWV 118, at the Count’s

funeral in 1740. For almost

a decade afterwards the

cantata remained

undisturbed, until in 1735

the text was revised once

more, probably by Picander,

when it assumed the title

“Kommt, eilet und laufet”

and was termed an oratorio

for the first time. A

singlefurther revision took

place sometime during the

1740s when Bach converted

the opening duet into a

chorus.

Though concise, in

comparison with the

Christmas Oratorio or those

written by German

contemporaries such as

Telemann, “Kommt, eilet und

laufet” qualifies for the

term, as opposed to that of

cantata, by the fact that it

contains passages of

narrative. But it differs

from many of its companions

inasmuch as the “dramatis

personae” are not named, and

biblical text is not used at

all, the role of Evangelist

thus being dispensed with.

So we have a work that,

while conforming in broad

terms with Bach’s sacred

cantata or Kirchenstück,

is nonetheless cast somewhat

in the Italian Baroque

oratorio tradition.

Bach’s biographer, Philipp

Spitta, remarked with

evident dismay that “all

that is most beautiful and

significant in the history

of the Resurrection... has

not been made any use of ”;

yet the skill with which

Bach set Picander’s text,

and his deeply affecting

response to it, suggest not

only that the composer found

it complementary to his own

requirements but that the

sacred context was envisaged

from the very first. There

are no anomalies between

words and music here and the

often vivid, always masterly

word-painting with which the

work is generously endowed

suggests a close

identification by Bach with

his textual subject matter.

The opening orchestral

Sinfonia is in two strongly

contrasting parts: first, a

richly scored D major Allegro

for flute, two recorders, two

oboes, oboe d‘arnore, three

trumpets, timpani, strings

and continuo with an

important bassoon part. This

is followed by a poignantly

expressive Adagio in

B minor for solo oboe - Bach

later designated this

movement for a transverse

flute - over a dotted string

accompaniment at the

conclusion of which it seems

at least possible that Bach

once intended a return to

the opening section. As it

stands the voices enter in

the oratorio's third

section, which takes up the

character, key, metre and

instrumentation of the

opening movement. Written as

a duet for tenor and bass

with chorus, this movement

may originally have

provided, as Arnold Schering

and others have suggested,

the finale of a lost

concerto, the preceding

sections providing its first

and second movements.

The remaining arias, one

each for soprano, tenor and

alto respectively, are all

of high quality. The first,

accompanied by flute or

violin obbligato, is in B

minor and is a joyful

contemplation of the soul.

In the second aria, one of

the expressive peaks of the

oratorio, the voice is

accompanied by two treble

recorders doubling muted

strings at the octave. The

third aria introduces an

oboe d'amore as obbligato,

with the strings. This

dance-like movement in the

bright and radiant key of A

major urgently asks the

question “Tell me quickly.

where can I find Jesus,

whommy soul loves?" And at

the close of the second

section leading back to the

da capo Bach

intensifies this pasionate

longing with a brief

four-bar adagio at

the words "for without You

my heart is sorely orphaned

and distressed." A final

chorus reintroduces the full

instrumental forces of the

opening. Cast in [wo parts (adagio-allegro)

rather in the manner of a

French ouverture, it brings

the oratorio to a brilliant

conclusion.

Ascension Oratorio, BWV

11

Bach himself called this

work Oratorium auf

Himmelfahrt (Oratorio

for Ascension). He wrote it

in 1735 and performed it at

Leipzig on the Feast of the

Ascension (19 May) that

year. Although BWV 11 is

hardly longer than a great

many of the church cantatas

- the Biblical account of

the Ascension is, after all,

comparatively brief compared

with the Christmas and

Epiphany stories which Bach

had used as the basis of his

extended Christmas Oratorio

of the previous year - it is

an oratorio in more than

just its name. It contains,

for instance, lines of New

Testament scripture, drawn

mainly from the Gospels of

St Mark, St Luke and the

Acts of the Apostles,

presented by a Narrator.

Interspersed with these are

commentaries and reflections

on the narrated text; thus,

unlike the cantatas, which

tell no continuous story,

and among which it should

not be classified, the

oratorio relates the

sequence of events

surrounding Christ’s

Ascension into Heaven. In

common with the Christmas

Oratorio, that for Ascension

incorporates music which

Bach had written earlier but

which nonetheless shows

evidence of careful revision

to suit its new context and

circumstances. Indeed, only

the four narrative sections

for the Evangelist, the two

accompanied recitatives and

the centrally placed chorale

would appear to have been

newly composed for the

oratorio.

The work, of which Bach’s

autograph score has been

preserved and of which, more

recently, his own vocal and

instrumental parts have come

to light, begins with a

vigorous D major chorus,

richly orchestrated for

three trumpets, pairs of

oboes and flutes, timpani,

strings and continuo. The

music had already been heard

both in a cantata

inaugurating the renovated

Thomasschule in 1732 and in

another celebrating the

nameday of Augustus III the

following year. Then follows

a sequence of recitatives,

arias and two chorales. As

in the Christmas Oratorio

and the two great Passions

the declamation of the tenor

Evangelist is in recitativo

semplice, whereas the

reflective non-Biblical

recitatives are accompanied

in a variety of ways. A

single exception to this

pattern is the affecting

duet, for tenor and bass, of

the two men in white

apparel. Two arias only

break up what is otherwise

an almost continuous pattern

of recitative. The first, in

A minor, for alto voice,

violins and continuo was

parodied from a secular

cantata which Bach had

written a decade earlier. In

its final and best known

form it became the Agnus Dei

of the Mass in B minor, BWV

232. The second, in G major,

for soprano with flutes,

oboe, violin, viola but

without continuo, may also

be a parody composition from

the same work none of whose

music, however, has

survived. in each of the two

chorale-based movements Bach

harmonises a different hymn

melody. The first (No. 6) is

the melody “Ermuntre dich,

mein schwacher Geist” while

the second is a

harmonisation of the tune

“Von Gott will ich nicht

lassen," which serves as a

cantus firmus sustained in

the vocal soprano line. This

is accompanied by the full

orchestra and brings the

oratorio to a resonant

conclusion.

Nicholas

Anderson

|

|

|

|