|

|

1 CD -

442 779-2 - (p) 1995

|

|

SECULAR

CANTATAS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann

Sebastian BACH (1685-1750) |

SCHWEIGT

STILLE, PLAUDERT NICHT, BWV 211 -

Coffee Cantata

|

|

25' 51" |

|

|

Text:

Christian Friedrich Henrici (Picander) |

|

|

|

|

-

Recitativo (Tenor): "Schweight

stille, plaudert nicht"

|

0' 34" |

|

1

|

|

- Aria (Bass):

"Hat man nicht mit seinen Kindern"

|

2' 57" |

|

2

|

|

-

Recitativo (Bass, Soprano): "Du

böses kind, du loses Mädchen"

|

0' 40" |

|

3

|

|

- Aria (Soprano):

"Ei! Wie schmeckt der Coffee suße"

|

4' 32" |

|

4 |

|

- Recitativo

(Bass, Soprano): "Wenn du mir

nicht den Coffee läßs"

|

1' 02" |

|

5 |

|

- Aria (Bass):

"Mädchen, die von harten Sinnen" |

2' 52" |

|

6 |

|

-

Recitativo (Bass,

Soprano): "Nun folge, was

dein Vater spricht" |

0' 50" |

|

7 |

|

- Aria (Soprano):

"Heute noch, lieber Vater, tut es

doch" |

6' 42" |

|

8

|

|

- Recitativo

(Tenor): "Nun geht und sucht der

alte Schlendrian" |

0' 47" |

|

9 |

|

- Choir (Terzett:

Soprano, Tenor, Bass): "Die Katze

läßt das Mausen nicht"

|

4' 55" |

|

10

|

|

LAßT

UND SORGEN, LAßT UNS WACHEN, BWV 213

- Hercules auf dem Scheide-Weg |

|

48' 00" |

|

|

Text:

Christian Friedrich Henrici (Picander) |

|

|

|

|

-

Choir (Ratschluß der Götter): "Laßt uns

sorgen, laßt uns wachen"

|

5' 52" |

|

11 |

|

-

Recitativo (Alto): "Und wo? Wo ist

die rechte Bahn" |

0' 40"

|

|

12

|

|

-

Aria (Soprano): "Schlafe, mein

Liebster" |

9' 42" |

|

13 |

|

-

Recitativo (Soprano, Tenor): "Auf!

folge meiner Bahn" |

1' 16" |

|

14 |

|

-

Aria (Alto): "Treues Echo" |

5' 19" |

|

15 |

|

-

Recitativo (Tenor): "Mein

hoffnungsvoller Held!" |

0' 52" |

|

16 |

|

-

Aria (Tenor): "Auf meinen Flügeln

sollst du schweben" |

5' 28" |

|

17 |

|

-

Recitativo (Tenor): "Die weiche

Wollust locket zwar" |

0' 37" |

|

18 |

|

-

Aria (Alto): "Ich will dich nicht

hören" |

4' 26" |

|

19 |

|

-

Recitativo (Alto, Tenor): "Geliebte

Tugend" |

0' 43" |

|

20 |

|

-

Aria (Duett: Alto, Tenor): "Ich bin

deine" |

8' 24" |

|

21 |

|

-

Recitativo (Bass): "Schaut, Götter,

dieses ist ein Bild" |

1' 08" |

|

22 |

|

-

Choir and Arioso (Choir of the

Muses, Bass): "Lust der Völker" |

3' 14" |

|

23 |

|

|

|

|

Barbara

Bonney, Soprano (Lieschen;

Wollust)

Ralf Popken, Alto (Herkules)

Christoph Prégardien, Tenor

(Erzähler; Tugend)

David Wilson-Johnson, Bass

(Schlendrian; Merkur)

|

ORCHESTRA AND CHOIR

OF THE AGE OF ENLIGHTENMENT

Richard Wynn Roberts, Countertenor

(Echo in BWV 213)

Elizabeth Wallfisch, VLeader, firs

violin

Jan Schlapp, Viola (BWV 213)

Annette Iserius, Viola (BWV 213)

Lisa Beznosiuk, Flute (BWV 211)

Anthony Robson, Oboe and Oboe

d'amore (BWV 213)

Richard Earle, Oboe (BWV 213)

Susan Sheppard, Cello

John Toll, Harpsichord

Gustav LEONHARDT, Direction |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Henry Wood-Hall,

London (England) - Gennaio 1994

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Artist and

reppertoire production

|

|

Stef Collignon

|

|

|

Recording producer |

|

Hein Dekker

|

|

|

Balance engineer

|

|

Ko Witteveen

|

|

|

Recording

engineer

|

|

Frans van Dongen

|

|

|

Tape editor

|

|

Gosia Jankowska

|

|

|

Design

|

|

Stidio R + M |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Nessuna

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Philips | LC 0305 |

442 779-2 | 1 CD - durata 74'

01" | (p) 1995 | DDD |

|

|

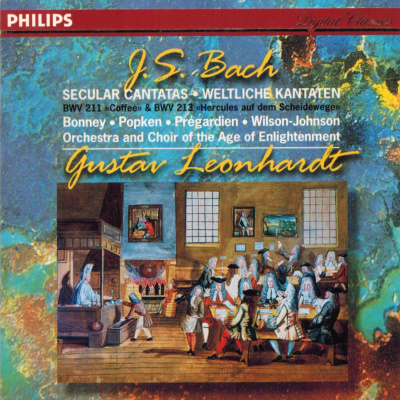

Cover Art

|

|

Coffee House, England

(Anon. c.1704), London, British

Museum

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

A

NEW CREATIVE OUTLET

In

1723 Bach was appointed

Kantor of the St Thomas

School in Leipzig and

Director of Music at the

city’s main churches. His

first five or six years at

Leipzig were spent mainly in

composing, rehearsing and

performing an incomparable

repertoire of church music:

cantatas, Passions and other

works. He seems to have

immersed himself in the task

with wholehearted devotion,

as though his earlier career

had been in some way a

preparation for it. Then, in

the spring of 1729, he found

an entirely new and

completely different outlet

for his creativity when he

took over the directorship

of a collegium musicum, or

musical society, which the

composer G.P. Telemann had

founded in Leipzig in 1702.

There are scarcely

half-a-dozen original church

pieces that can be dated to

the last two decades of

Bach’s life (1730-50); his

sacred compositions from

this period, including the B

minor Mass and the Christmas

Oratorio, consist almost

entirely of reworkings of

earlier pieces.

The collegium musicum, which

met each week at the coffee

house of Gottfried

Zimmermann in the

Catherinenstrasse, was

attended mainly by

university students along

with some professional

musicians; Bach’s eldest

sons, who were by that time

competent performers, were

also no doubt regular

attenders. The society had

two spheres of activity: one

was the “ordinary” concerts

(advertised as such) on a

relatively modest scale that

took place at Zimmermann's

premises: the other was the

provisivn of music for royal

or academic occasions at

various venues in Leipzig,

often in the open air, for

which the regular resources

of the collegium would be

augmented by extra players

and singers, frequently in

very large numbers indeed.

The present recording

exemplifies both types of

activity. We do not know for

certain what music was

played at the “ordinary”

concerts; the programmes

presumably included

concertos (esepcially

harpsichord concertos) and

sonatas by Bach himself. But

we do know that they also

included vocal music, and it

is very likely, given the

subject matter and the

relatively small forces

involved (three vocal

soloists, flute, strings and

continuo), that the

so-called “Coffee” Cantata

was included in them; it

dates from about 1734. The

text, by Bach’s favourite

Leipzig librettist, C.F.

Hemici (known as

“Picander”), presents a

little drama in which the

young Lieschen (soprano)

earns the disapproval of her

father Schlendrian (bass)

because of her addiction to

coffee, and then uses the

situation to her advantage

by agreeing to give up the

beverage if she is allowed

to marry the one she loves.

But then, in a surprising

addition to Picander’s

printed libretto, we learn

that her marriage contract

will contain a clause

obliging her husband to

allow her to continue her

indulgence.

This extra twist to the tale

was no doubt designed to

appeal to to Zimmermann and

his clientele, but it also

allows the narrator (tenor),

who has not been heard since

the opening of the work, to

sing another recitative and

to join with the other two

soloists in a final trio

which points the moral in

suitably springhtly fashion:

"Just as the cat won't leave

the mice alone, so the young

lady remains wedded to her

coffee." The final ensemble

of soloists also benefits

from some agile divisions on

the flute, which is

otherwise heard only as an

obbligato instrument in

Lieschen's first aria, where

it serves to convey

something of her coquettish

demeanour, Schlendrian's

first aria, accompanied by

the string band, is no less

expressive of his

blustering, irascible

character.

The other two arias

effectively point to the

"generation gap" separating

father and daughter:

Schlendrian attempts to lay

down the law in an

oldfashioned aria, "Mädchen,

die von harten Sinnen," with

ponderous chromaticism and

fussy chord changes;

Lieschen's response to his

offer of a bridegroom, on

the other hand, is expressed

in light, galant phrases

supported by simple

harmonies and a hint of

modish "alberti" figuration

from the harpsichord. The

"Coffee" Cantata is the

nearest that Bach came to

writing an opera (though

some of the church cantatas

in dialogue form are

scarcely less dramatic in

concept); it gives us some

idea of where his strenghts

and weaknesses might have

lain if he had been given

the opportunity of trying

his hand at a genuinely

operatic genre.

During the summer months

Bach's collegium musicum

transferred its activities

from Zimmermann's coffee

house to his garden outside

the city walls, and it was

there that Hercules at

the Crossroads was

performed on 5 September

1733 in celebration of the

eleventh birthday of the

Elector of Saxony's son,

Prince Friedrich Christian.

Strings and continuo

joined for this by two

oboesm two horns and a

fourpar choir. The

librettist was once again

Picander, but this

time his verses do no more

than eulogise the young

prince in vapid and

conventional terms,

Friedrich Christian is

represented by the Greek

hero Hercules (alto; an

unlikely impersonation,

since the royal child was,

by all accounts, delicate

and suckly), who must choose

between Pleasure (soprano)

and Virtue (tenor) to be his

guiding principle in life,

Pleasure sets out her

attractions in a languorous

aria accompanied by the

strings, but in the

succeeding recitative Virtue

intervenes to urge Hercules

to take a different path. In

a duet with Echo (alto; the

obbligato oboe d'amore

furnishes a second echo for

many of the singer's

phrases) he is persuaded to

renounce the allurements of

Pleasure, and in an

ebergetic, clean-limbed

aria, accompanied by oboe,

violin and continuo, Virtue

urges his claims to the

hero's affections.

Predictably enough, Hercules

renounces Pleasure and, in

what is remarkably like a

love duet, unites himself

ith Virtue, Mercury (bass)

calls upon the gods to

witness Hercule's choice and

the people express their

approval of the young

Friedrich Christian in a

chorus which resembles the

final ensemble of the Coffee

Cantata in its folk-like and

dance-like qualities and in

its rondo structure

(A-B-A-C-A) with substantial

ritornellos and instrumental

divisions (this time on

first violin).

Like several other Bach

works of this type, Hercules

at the Crossroads is

described in the printed

text as a "Drama per

musica," a term commonly

employed (with slightly

different spelling) for

italian opera of the period.

There is little in the way

of drama in Bach's

celebratory cantata,

however, and he and his

librettist found little

difficulty in adapting most

of the work (all of it, in

fact, except the recitatives

and the final chorus) as

movements in the Christmas

Oratorio (1734-45), where

the music has, of course,

become much better known.

The adaptations are on the

whole very successful. The

opening chorus required no

alteration beyond a change

of text to introduce Part 4

of the oratorio; Pleasure's

languorous "Schlafe, mein

Liebster" became a lullaby

for the Christ-child in Part

2, with a change of key and

instrumentation; and the

other movements were

similarly adapted to their

new role with a minimum of

alteration, though Hercule's

solo aria, familiar in

English translations of the

oratorio as "Prepare

thyself, Zion," required a

new, smoother type of

articulation (a staccato

delivery is specified

in the cantata). Only the

aria "Treus Echo dieser

Orten" may be said to fit

rather uncomfortably into

the oratorio, where, to

moderm ears at least, its

playful echo phrases are apt

to sound out of keeping with

an earnest religious text.

The Christmas Oratorio is

not likely to be replaced in

the affections of most

audiences by Hercules at

the Crossroads and th

other secular cantatas that

Bach parodied for his sacred

masterpieces, but it is

salutary to be made aware of

the original text, and

context, for which the music

was written, and to be

reminded of how a composer

committed to perfection in

his art will clothe even the

most mundane and

conventional sentiments and

occasions, with music of the

highest quality and

originally.

Malcom

Boyd

|

|

|

|