|

|

1 CD -

446 000-2 - (p) 1995

|

|

VOLUNTARIES,

SUITES AND GROUNDS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Henry

PURCELL (1658-1695) |

Voluntary

for Double Organ, Z 719 |

organ |

|

5' 17" |

1 |

|

Voluntary

in G, Z 720

|

organ |

|

3' 42" |

2

|

| John BLOW

(1649-1708) |

Voluntary in D

minor (for the Cornet

Stop) |

organ |

|

5' 15" |

3

|

|

Voluntary

in A

|

organ |

|

1' 34" |

4

|

|

Voluntary

in G

|

organ |

|

3' 00" |

5 |

|

Voluntary in D

minor |

organ |

|

3' 02" |

6 |

| Henry PURCELL

|

Suite No. 4 in A

minor, Z 663

|

harpsichord |

|

6' 00" |

7 |

|

A New Ground in

E minor, Z T682 |

harpsichord |

|

2' 26" |

8 |

|

A New Irish Tune

in G (Lilliburlero), Z 646

|

harpsichord |

|

0' 45" |

9 |

|

Riggadoon

in C, Z 653 |

harpsichord |

|

0' 49" |

10

|

|

Sefauchi's

Farewell, Z 656

|

harpsichord |

|

1' 50" |

11 |

|

Suite No. 2 in G

minor, Z 661 |

harpsichord |

|

8' 25" |

12

|

|

Ground

in C minor, Z 681 |

harpsichord |

|

3' 29" |

13 |

|

Ground

in Gamut, Z 645

|

harpsichord |

|

1' 43" |

14 |

|

Suite

No. 5 in C, Z 666 |

harpsichord |

|

5' 48" |

15

|

|

Hornpipe

in E minor, Z T685 |

harpsichord |

|

0' 44" |

16 |

|

Suite

of Lessons in C, Z 665: Jigg

|

harpsichord |

|

1' 05" |

17 |

|

Suite

No. 7 in D minor, Z 668 |

harpsichord |

|

6' 22" |

18 |

|

|

|

|

|

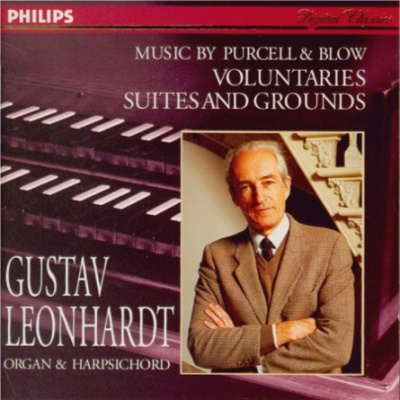

| Gustav

LEONHARDT, Organ & Harpsichord |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Grote Kerk, Hervormde

Gemeente, Edam (The Netherlands) -

Maggio 1994 (organ)

Doopsgezinde Gemeente, Haarlem

(The Netherlands) - Maggio 1994

(harpsichord)

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Artist and

reppertoire production

|

|

Stef Collignon

|

|

|

Recording producer |

|

Hein Dekker

|

|

|

Balance engineers

|

|

Hein Dekker | Ko

Witteveen

|

|

|

Recording

engineer

|

|

Ko Witteveen

|

|

|

Tape editor

|

|

Hans Meijer

|

|

|

Art direction

|

|

Tom Fricsen

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Nessuna

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Philips | LC 0305 |

446 000-2 | 1 CD - durata 62'

229" | (p) 1995 | DDD |

|

|

Cover Art

|

|

Photo by Geert

Kooiman

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

A

TOUCH OF THE WILD

The

keyboard music of Blow,

Purcell and their English

contemporaries forms a rich,

varied and surprisingly

large repertory. But it has

suffered invidious

comparison with the earlier

English virginalist school

and especially with the vast

and consistently good work

ofthe clavecinistes.

Its reception has also been

hampered because English

performance practice is not

as well understood as the

French; there are no

restorable late

seventeenth-century English

harpsichords to help us

recreate the sound; and

English organs, which never

had pedal boards, lack the

grandeur and mystique of

continental instruments. Yet

Blow’s organ works are

sophisticated and often

highly original, while

Purcell’s harpsichord suites

show a distinctive blend of

French and English styles

with unfailingly memorable

tunes.

Unlike the French, English

religious institutions did

not encourage keyboard

virtuosos. At the height of

his career Blow casually

resigned as organist of

Westminster Abbey in favour

of his pupil Purcell,

reassuming the post when the

younger man died in 1695.

Despite Purcell’s

responsibilities as a

keyboard player (he was also

one of the organists of the

Chapel Royal), hardly any

organ music by him survives.

The 1nstrument’s chief role

in the Anglican service was

to accompany the anthem, any

solo work being confined to

short improvised interludes

or “voluntaries.” It would

appear that only the more

contrapuntal of these were

ever written down. None

survives in Purcell’s own

hand, and it is not certain

that even the two very fine

voluntaries on this

recording are authentic

Purcell, although that “for

the double organ” in D minor

bears his hallmark: the main

theme is worked through a

series of strict,

contrapuntal variations

alternating with

toccata-like passages, one

of which applies dissonance

in Purcell's typically

expressive manner.

Blow’s organ music, which is

much more extensive and

indisputedly authentic, can

seem too academic and dry

or, at the other extreme,

rugged in its partwriting.

The voluntaries selected

here, however, are generally

well behaved - tuneful and

jolly, with few harmonic

quirks; apart, that is, from

the extraordinary Voluntary

No. 18. This is built on

relentlessly descending

chromatic scales which

produce wild, unorthodox

progressions and false

relations, shocking even by

Blow’s usual teeth-grating

standards. He is at his best

when, as here, the rules of

counterpoint are thrown to

the winds.

Purcell clearly preferred

the harpsichord to the

organ; he composed ten

suites after the French

manner and dozens of smaller

individual pieces and

arrangements. This is music

of high quality, but it

lacks the polish and

technical demands of Louis

Couperin or D’Anglebert.

Modern harpsichordists have

therefore tended to treat

Purcell’s harpsichord music

as a nursery repertory. But

its simplicity is deceptive,

especially as regards

rhythm. The discovery of an

autograph manuscript of

Purcell‘s harpsichord music

in November 1993, which came

too late to be reflected in

this recording. will cause a

reassessment of this aspect

of his output. The

manuscript shows that, while

Purcell clearly regarded the

harpsichord as a teaching

instrument, he took this

music very seriously indeed,

polishing and revising it.

For him, the suite was a

flexible collection of three

to five pieces. an almand and

corant forming the core,

with optional prelude,

saraband (both fast and slow

types). jig or hornpipe. The

new manuscript also proves

that Purcell made his own

keyboard arrangements of

songs and theatre pieces and

that, conversely. some

entr’actes for plays and

semi-operas may have been

conceived for the

harpsichord and later scored

for orchestra. Though

neither piece is found in

the keyboard autograph, both

the New Ground (an

arrangement of “Here the

Deities Approve” from the

1683 St Cecilia’s Day ode)

and the Ground in C minor

(based on the countertenor

air “With Him He Brings the

Partner” from Ye tuneful

Muses, a welcome ode

for King James II) were

undoubtedly made by Purcell

himself. The melodies are

copiously though tastefully

ornamented, and the basso

continuo written out in a

curious, syncopated pattern

fashionable at the time.

Among the other single

pieces included here is A

New Irish Tune, the

famous Lilliburlero,

which may actually have been

composed by Purcell, though

it was quickly taken up for

broadside political songs

(usually anti-Jacobite and

thus anti-Irish); it retains

these imperialistic

overtones to this day as the

signature tune of the BBC

World Service. Sefauchi's

Farewell, a wistful

and beautifully balanced

melody, refers to the

castrato Giovanni Francesco

Grossi (known as “Siface”),

who sang in the Catholic

Chapel of James II in the

late 1680s. Since the chapel

was effectively depriving

Purcell of employment, this

farewell may have been “good

riddance.” As has often been

remarked, the Ground in G is

based on the same basso

ostinato later used by Bach

for the Goldberg Variations.

In fact, the third section

of the Purcell comes

remarkably close to

anticipating the Goldberg

theme itself.

The three suites included on

this recording do not suffer

comparison with any

superficially similar

continental works,

especially the almands and

corants. Although indulging

in the brisé or

broken-chord style, Purcell

concentrates on the melody,

at least in the first strain

of each piece; in the second

he usually breaks

appealingly into figuration,

from which a new tune often

emerges. Despite the formal

constraints of binary dances

in the style brisé,

Purcell’s imagination is

never fettered, his genius

for melody never submerged

under the weight of

ornamentation. Nowhere is

this freedom better heard

than in the almand from the

Suite No. 5 in C. The first

strain is a routine, stately

exposition, but the second

expands majestically with a

series of fresh ideas which

are barely containable

within the miniature

structure. This notion seems

to be confirmed by the newly

discovered autograph, which

is the working draft:

Purcell miscalculated how

much space this piece would

require and was forced to

complete it on a previous

page. His characteristically

bold, neat writing gives way

to a scrawl, with ink

splattered all over the

page. Even within the

detached and refined world of

the French harpsichord

suite, Purcell’s passion

never cooled.

Curtis

Price

|

|

|

|