|

2 LPs

- 6775 018 - (p) 1975

|

|

| 2 LPs -

RL 30428 - (p) 1980 |

|

| 2 CDs -

SB2K 63185 - (c) 1997 |

|

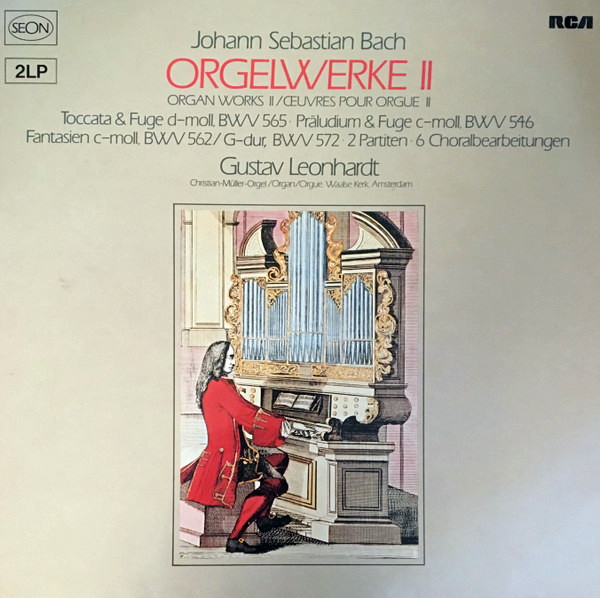

ORGELWERKE II

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

BACH (1685-1750) |

Toccata

and Fugue in D Minor, BWV 565 |

|

7' 18" |

A1 |

|

Fantasia

in C Minor, BWV 562 |

|

5' 16" |

A2

|

|

Fantasia in G Major, BWV 572

|

|

10' 11" |

A3

|

|

Partite

diverse sopra "O Gott, du frommer Gott",

BWV 767

|

|

17' 54" |

B1 |

|

Chorale

Prelude "Valet will ich dir Geben",

BWV 736 |

|

4' 44" |

B2 |

|

Prelude

and Fugue in C Minor, BWV 546 |

|

12' 59" |

C1 |

|

Chorale

"Allein Gott in der Höh'", BWV 663 |

|

8' 30" |

C2 |

|

Chorale

"O Lamm Gottes, unschuldig", BWV 618 |

|

4' 20" |

C3 |

|

Chorale

Prelude "Jesus Christus, unser

Heiland", BWV 665 |

|

4' 55" |

D1 |

|

Chorale

Prelude "Jesus Christus, unser Heiland",

BWV 666 |

|

3' 10" |

D2 |

|

Chorale

Prelude "Wir Christenleut' hab'n jetzund

Freud", BWV 710 |

|

2' 22" |

D3 |

|

Partite

diverse sopra "Christ, der du bist der

helle Tag", BWV 766 |

|

10' 37" |

D4 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Gustav

Leonhardt, at the Christiaan Müller

Organ of the "Waalse Kerk" Amsterdam,

built 1733/34 |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Marzo 1973

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Recording Supervisor |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

Recording Engineer

|

|

Dieter Thomsen

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Seon (Philips) | 6775

018 | 2 LPs - durata 45' 23" - 46'

53" | (p) 1975 | ANA

Seon (RCA Red Seal) | RL 30428 | 2

LPs - durata 45' 23" - 46' 53" |

(p) 1980 | ANA

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Sony | SB2K 63185 | 2

CDs - durata 70' 11" - 77' 34" |

(c) 1997 | ADD

|

|

|

Original Cover

|

|

Christoph Weigel

(1654-1725) - Organist kupferstich

aus "Theatrum Musicum", Nürnberg,

1720

|

|

|

Note |

|

Il doppio CD Sony

contiene anche brani di altra

pubblicazione (Seon 6775 001).

|

|

|

|

|

Compared with

many other musical giants of

history Johann Sebastian

Bach was a ,,late

developer”. He matured

slowly, but steadily. It was

not until he was between 25

and 30 years of age, i. e.

during the Weimar period,

that he acquired complete

mastery of his art, a

mastery, however, that was

to be maintained

consistently right up to the

end of his life. Although

the process of “finding

himself” was a gradual one,

this does not, of course,

mean that all his early

works can be dismissed as

having little artistic merit

- on the contrary, even they

tower far above anything

similar written by his

contemporaries and provide

ample glimpses of latent

genius. This particularly

applies to his early works

for organ, the instrument

with which he naturally felt

the closest affinity, being

the one in constant daily

use. Here we find

germinating the ideas that

were to come to fruition in

the great masterpieces of

the later years.

One of the most gripping and

most popular of all Bach’s

early works is the famous Toccata

in D minor (BWV 565).

Full of primal energy, the

work sets off in extemporary

manner with powerfully

descending unisoni, broken

chords and chords of the

diminished seventh, until

finally the pedal enters

with impressive solemnity.

The fugue, whose theme has

already been intimated in

the opening Adagio,

temporarily relaxes the

mood, but the dramatic

intensity returns again with

the reappearance of the

toccata section.

The Fantasia in G major

(BWV 572) is a typical

product of the emotionally

exuberant ,,Sturm und Drang”

years. Although actually

divided into three sections

- the young Bach uses French

designations for the

movements: Très vitement,

Grave, Lentement - the work

gives the impression of

being one long ecstasy of

sound and colour. In the

third section, hidden

beneath the glittering array

of broken chords, is some

genuine fivepart

counterpoint which subtly

refers back to various

elements in the preceding

sections. Most compelling is

the extensive Grave middle

section with its weighty

appoggiaturas, diminished

chords and sweeping melodic

curves. The effect created

by the bass ascending in

semibreves diatonically over

two octaves is quite

monumental in its grandeur.

The two C minor works are

products of Bach’s mature

years. The Fantasia BWV

562 (there is a fugue

belonging to it, which is

unfortunately unfinished) is

an unusually expressive

compositon developed out of

a single musical idea. Two

pedal points at the begin

ning and at the end of the

work form an effective

frame. The opening movement

of the Prelude and Fugue

in C minor (BWV 546)

is likewise very clear in

its construction. A work of

mighty proportions it serves

to depict strong, passionate

emotion. After the initial

powerful pedal point come

motives familiar to us from

the final chorale of Part I

of the ,,Matthew Passion”

and other works. At the

first climax Bach already

uses the chord of the

Neapolitan sixth, with Bach

always a sign of the

exceptional. The episode

employs a double theme which

substantially determines the

musical course of events

right up to the close of the

movement. The following

fivepart fugue is based on

two themes: an evenly

constructed, solemnly

striding theme and a more

mobile one, of which, for

the most part, only the

opening is developed,

however. The tremendous

build-up on the dominant

just before the pedal enters

for the last time is a most

impressive preparation for

the coda.

The chorale partitas

are some of Bach’s very

earliest pieces and, unlike

other of his youthful works,

can be dated with certainty

“c.1700” (although they were

most probably revised

later). The influence of

Georg Böhm is very apparent.

In the partitas Bach applies

the techniques of the

secular song-and-variation

form to the chorale.

Although each “partita”, i.

e. variation, is supposed to

correspond to the text of

one of the verses (quoted

before it), the influence of

the text on the music is, at

this stage, not always very

great. In O Gott, du

frommer Gott (BWV 767)

the concept of death in the

8th partita inspires Bach to

treat the material in an

expressive chromatic manner.

The subject of death was,

incidentally, throughout his

life the inspiration of some

of his finest music. In the

extended final partita, no.

9, he uses a fanfare motive

to illustrate the

“resurrection of the dead”.

The choral partita Christ,

der dn bist der helle Tag

(BWV 766) is extremely sweet

and gentle in character, at

times almost sentimental.

There is much figurative and

metaphoric treatment, the

young composer often

displaying a naive pleasure

in the pictorial. The warm,

intimate tone of no. 2 is

closely related to the text:

“Lord, keep us safe this

night, we pray”; the triplet

movement in no. 6 depicts

the descending and ascending

of the angels, and the

dropping, closing together

motives in no. 7 suggest the

“shutting eyelids”.

In Bach’s chorale preludes,

however, no matter from

which period they come, the

literary text receives a

musical interpretation hard

to surpass. In O Lamm

Gottes unschuldig (BWV

618) from the

“Orgelbüchlein” the cantus

firmus rendered in canon at

the fifth symbolizes the

fulfilment of divine will

through the Son, the oneness

of God the Father and

Christ. The contrastin

“sobbing” motive (cf. BWV

546 above) symbolizes

mourning. Wir

Christenleut’ (BWV

710) is one of Bach’s finest

chorale trios, with much

imitative work and stretto

treatment of the melody. In

Valet will ich dir geben

(BWV 736) the proud,

masculine tune appears in

the bass. To symbolize the

triumph over death Bach uses

nimble upbeat figures with

leaps to the fourth and

fifth, figures which bound

with even more enthusiasm in

the third line. Clearly an

early work, Allein Gott

in der Höh' sei ehr'

(BWV 663) presents the

imaginatively ornamented

cantus firmus in the tenor,

in the manner of the

traditional North German

chorale fantasia. In Jesu

Christus, unser Heiland

(BWV 665), based on the

Lutheran communion hymn, the

text is reflected in great

detail. The continually

upward-striving counterpoint

of the first line is

obviously meant to represent

the soul’s striving to reach

its Savior, the syncopations

of the second line the

struggle for God’s love. The

“bitter suffering” of the

third line is symbolized by

agonising chromatic

descents, the “torments of

hell” of the fourth by the

upwardrushing

demisemiquavers. The chorale

prelude BWV 666 based on the

same hymn tune is unique in

that it employs the manuals

almost exclusively (only at

the end a pedal note is used

for support). On the whole

this version is much more

neutral. The someWhat

rapturous style of the close

suggests that it is an early

work.

Lothar

Hoffmann-Erbrecht

English

translation by Avril Watts

|

|

|

|