|

1 LP -

RL 30393 - (p) 1980

|

|

| 1 CD -

SBK 61786 - (c) 1999 |

|

| PRELUDII,

ALLEMANDE, CORRENTI, GIGHE, SARABANDE,

GAVOTTE E FOLLIA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Arcangelo CORELLI (1653-1713) |

(Sonate)

in G Minor, op. 5 Nr. 7 |

|

9' 19" |

A1 |

|

- Preludio

(Vivace) · Corrente (Allegro) ·

Sarabanda (Largo) · Giga (Allegro)

|

|

|

|

|

(Sonate)

in A Minor, op. 5 Nr. 8 |

|

8' 54" |

A2 |

|

- Preludio

(Largo) · Allemanda (Allegro) ·

Sarabanda (Largo) · Giga (Allegro)

|

|

|

|

|

(Sonate) in E-flat Major,

op. 5 Nr. 9 |

|

8' 44" |

A3 |

|

- Preludio

(Largo) · Giga (Allegro) · [...]

(Adagio) · Tempo di gavotta (Allegro)

|

|

|

|

|

(Sonate)

in C Major, op. 5 Nr. 10 |

|

8' 50" |

B1 |

|

- Preludio

(Adagio) · Allemanda (Allegro) ·

Sarabanda (Largo) · Gavotta (Allegro) ·

Giga (Allegro) |

|

|

|

|

(Sonate)

in B-flat Major, op. 5 Nr. 11 |

|

7' 16" |

B2 |

|

- Preludio

(Adagio) · [...] (Allegro) · [...]

(Adagio-Vivace) · Gacotta (Allegro)

|

|

|

|

|

"Follia"

in G Minor, op. 5 Nr. 12 |

*

|

9' 30" |

B3 |

|

|

|

|

|

Frans Brüggen,

Recorder (in f' after P. Bressan, London,

c. 1710 of Frederick Morgan, Melbourne,

Amsterdam, 1979)

|

|

| Anner Bylsma,

Voloncello (Mattio Goffriller, Venezia,

1669) |

|

| Gustav

Leonhardt, Harpsichord

(Martin Skowroneck, Bremen, 1960) |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Lutherse Kerk,

Haarlem (Holland) - Agosto 1979

& Marzo 1980 *

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Recording Supervisor |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

Recording Engineer

|

|

Teije ven Geest

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Seon (RCA Res Seal) |

RL 30393 | 1 LP - durata 53' 31" |

(p) 1980 | ANA

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Sony | SBK 61786 | 1

CD - durata 53' 31" | (c) 1999 |

ADD

|

|

|

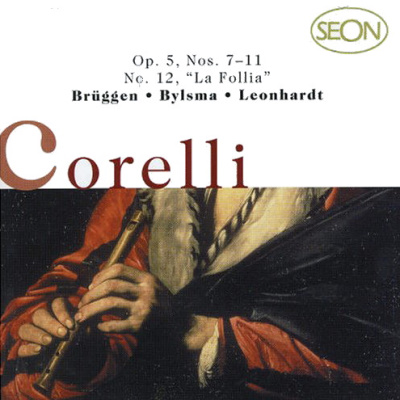

Original Cover

|

|

Meister des 17./18.

Jh., Blockflötenspieler, Oil

painting, c. 1705 (owned by Dr.

Carl Dolmetsch, Haslemere/England)

|

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

Before the

remarkable revival of

interest in "early" music

that has occurred in the

20th century, the only

composers of the Baroque era

to be known to the general

public were Bach and Handel.

Nowadays, when there are 30

recordings of Vivaldi's Four

Seasons in the catalogue and

a Pachelbel canon can become

an international

best-seller, it is

surprising that one of the

most celebrated Italian

composers of the late

Baroque, whose work were

still said to be quoted like

those of a classical author

nearly a century after their

publication, is although,

discussed extentively in

music history books, less

often performed. The

composer in question is

Arcangelo Corelli

(1653-1713), who spent his

working life in Rome, mostly

in the service of cardinal

Ottoboni, a nephew of the

Pope and great patron of the

arts, particularly music.

Ottoboni gave Corelli

lodgings at his palace and

treated him more as a friend

than a servant. There, as

Christopher Hogwood has

written, he lived "in an

atmosphere of peace and

serenity that few other

composers ever achieved, he

was, by all accounts, a midd

man, not over-generous,

given to collecting pictures

and dressing in black

(according to Handel). His

works were only published

after the utmost refining

and reworking, and after

they had been thoroughly

tested in performance".

These monumental

publications, all for

strings, consisted of four

sets of 12 trio sonatas

(first issued

1681/1685/1689/1694), a set

of solo sonatas (1700) and

one of concerti grossi

(1714). They achieved

unparallelled success. His

sonatas, for example, were

reprinted no fewer than 78

times during his lifetime

and another 30 during the

next century, 18th-cntury

writers fell over themselves

in their esagerness to

praise them. "Lì music can

be immortal", wrote Roger

North, "Corelli's consorts

(ensemble music) will be

so", and Sir John Hawkins

called his music "the

language of nature". Other

composers copied his styles

and forms slavishly.

Ironically, the very

qualities Corelli's

contemporaies admired in his

music seem to be responsible

for its present relative

neglect. Taste has changed.

They rejoiced in his strict

observance of the law's of

harmony, his refinement, his

restraint and moderation,

his lack of novelry and

surprise, his avoidance of

extreme virtuosity, and

above all the universality

of his appeal: "his

compositions", said Hawkins,

"are equally intelligible to

the learned and unlearned".

To the modern ear his music

can seem merely dull. But in

retrospect we can see that

Corelli achieved a

remarkable synthesis of the

various strands of style,

form and technique in the

Italian music of his day. He

refined the priciples of

thematic unity in and

between movements,

established the

slow-fast-slow-fast order of

movements as the norm for

sonatas (though he was less

regular in this than his

imitators), and above all

consolidated the major-minor

system of tonality.

Moreover, in practice his

music may not have been as

serene as it looks on the

printed page. "A person who

had heard him perform",

wrote Hawkins, "says that

whilst he was playing on the

violin it was usual for his

countenance to be distorted,

his eyes to become as red as

fire, and his eyerballs to

roll as in agony". Corelli's

Opus 5 consists of 11

sonatas and a set of

variations. The first six

sonatas (not included on

this record) are sonate da

chiesa (church sonatas),

made up for the most part of

parely abstract movements of

a serious character. The

five of Part II are sonate

da camera (consort sonatas),

consisting of dance

movements and a few abstract

movements in a lighter vein.

Corelli, in fast, did not

call duetti sonatas but

"Preludii, Allemande,

Correnti, Gighe, Sarabande,

Gavotte". The final work in

the collection is a set of

23 variations on La Follia,

a sixteen-bar ground bass

that had been quied as the

basis of variations for well

over a century and has by

then picked up an

"accompanying" melody in

chaconne rhythm. This is

something of a tour de

force, particularly in

bowing technique.

Corelli's sonatas, solo and

trio, were played in England

from the start. Roger north

wrote in 1728 of their

pre-eminences rôle in the

establishment of the Italian

style there in place of the

prevailing French taste. His

firm collection "cleared the

ground of all other sorts of

music whatsoever. By degrees

the rest of his consorts,

and at last the concertos

came, all which are to the

musicians like the bread of

life". The Opus 5 sonatas

were eagerly anticipated in

london. They were advertised

for sale by subscription by

John Crouch, one of the

royal violinists, the year

before publication, and the

following years, "being

newly brought from Rome",

they were sold by John

Banister and Robert King,

also royal violinists and,

significantly, the leading

concert promoters of the

day. We know from

contemporaneous

advertisements that during

the next decade they were

performed in the intervals

of plays at Drury Lane by

Gasparo Visconti (alias

Gasperini), "five years

Corelli's scholar), and in

concerts by the leading

English violinists, Dean,

Viner, Thomas Baston, and

Corbett.

There was no shortage of

good amateur violinists in

England, but the instrument

of the common (middle class)

man was the recorder. The

public wanted to hear and

play the latest fashion,

therefore publishers like

Walsh in London and Roger in

Amsterdam (who had an agent

in London), alwaysshrewd

businessmen, lost no time in

issuing Corelli's works in a

form that would appeal to

the greatest number of

performers: arrangements for

the recorder. In 1702, only

two years after Opus 5

appeared in Rome, Walsh

published a version

"transposed and made fit"

for treble recorder and

flute basso (sic!) "with the

approbation of several

eminent masters", who were,

however, apparently not

eminent enough to be named.

This is the basis of the

works on this record.

David

Lasocki

|

|

|

|