|

|

1 CD -

SK 48 080 - (p) 1992

|

|

| PIÈCES DE

CLAVECIN (after the original version for

viola da gamba, transcribed for

harpsichord by Jean-Baptiste Forqueray

(1699-1782) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Antoine

FORQUERAY (1672-1745) |

Suite

in D major |

|

22' 22" |

|

|

- La

Régent. Noblement et soutenu

|

4' 29" |

|

1

|

|

- La Tronchin.

Mouvement aisé |

3' 44" |

|

2

|

|

-

La Angrave. Très vivement * |

3' 28" |

|

3 |

|

- La Eynaud.

Fièrement |

2' 55" |

|

4 |

|

-

La Morangis ou La Plissay.

Mouvement de Chaconne * |

7' 46" |

|

5

|

|

Suite in G minor (transcribed for

harpsichord by Jean-Baptiste

Forqueray)

|

|

26' 57" |

|

|

-

La Marella. Vivement et

marqué |

3' 31" |

|

6

|

|

- La

Clément. Noblement et détaché |

6' 36" |

|

7 |

|

- Sarabande.

La d'Aubonne |

5' 19" |

|

8 |

|

- Le

Carillon de Passy. Légèrement sans

vitesse - La latour. Un peu plus

vif que la précédente pièce |

11' 31" |

|

9 |

| François COUPERIN (1668-1733) |

La

Superbe, ou la Forqueray (Troisième

livre, dixseptième ordre) |

|

4'

49"

|

|

|

-

Fièrement, sans lenteur (in E minor) |

4' 49" |

|

10 |

| Jacques DUPHLY (1715-1789) |

Pièces

de Clavecin (Troisième ordre) |

|

6' 14" |

|

|

- La

Forqueray. Rondeau (F minor) |

6' 14" |

|

11 |

|

|

|

|

| * Original compositions by J.-B.

Forqueray |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gustav LEONHARDT,

Harpsichord |

|

| (Harpsichord by

Nicholas Lefébure, Rouen, 1755) |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Lutherse Kerk,

Haarlem (Holland) - 11/12

Settembre 1991 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Recording supervisor |

|

Wolf Erichson |

|

|

Recording

Engineer / Editing

|

|

Stephan Schellmann

(Tritonus) |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Nessuna |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Sony "Vivarte" | LC

6868 | SK 48 080 | 1 CD - durata

60' 45" | (p) 1992 | DDD |

|

|

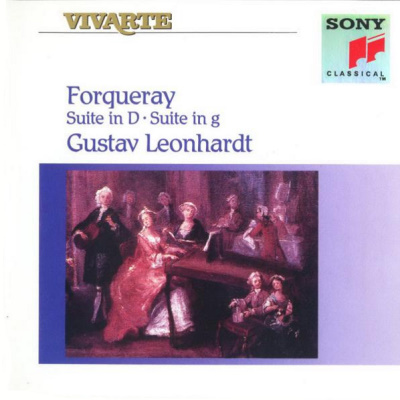

Cover Art

|

|

Le concert by

Anonymus (c.1750) - Paris, Private

Collection |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Musical

Portraits From the Era of

the Sun King and Louis XV

The reign of

the Sun King Louis XIV, the

so-called “grand siècle” is

often considerated to be the

golden age of French

harpsichord music. In fact yet

the works for harpsichord both

by François Couperin and by

Jean-Philippe Rameau were

actually composed after the

death of Louis XIV in 1715,

with the harpsichord attaining

its greatest popularity during

the reign of Louis XV

(1723-1774). It was this

latter period which was to

witness the creation of

instruments and compositions

of utmost perfection,

comparable to the contemporary

German works for harpsichord

and clavichord written in the

so-named empfindsam or

“sensitive” style by Carl

Philipp Emanuel Bach and

Johann Gottfried Müthel. This

golden age was, however, to

come to an end, caused by a

new orientation in French art:

the triumph of the Italian

over the French style,

combined with the “musical

invasion from the east”,

through composers such as

Johann Schobert and the

Mannheimer Johann Stamitz. The

harpsichord, as the instrument

of the “ancien régime” per se,

was doomed to a glorious if

melancholy demise, whilst the

fortepiano was already gaining

ground even in France. Even

the stalwart support of

Claude-Bénigne Balbastre, one

of the most important

representatives of French

rococo harpsichord music,was

to be in vain. After having

heard the harpsichord builder

Pascal Taskin play on an

English fortepiano, he

prophesied that the majestic

harpsichord would never be

dethroned by this “newsounding

thing”.

A contemporary and colleague

of François Couperin at the

court of Louis XIV was the

great gamba virtuoso Antoine

Forqueray who, together with

his son Jean-Baptiste, was the

most important representative

of a dynasty of musicians who

originated from Scotland. From

an early age, Antoine

Forqueray demonstrated such a

prodigious talent for the

gamba, that he not only played

before the Sun King at the age

of five, but was retained at

the court where he was brought

up with the other pages.

Following his appointment at

the age of seventeen as a

regular musician to the royal

court, he caused a great stir

with his unbelievable

virtuosity and his improvised

preludes and came to teach a

large number of distinguished

people, such as Philippe, Duke

of Orleans, later to become

the regent of France. As a

gamba player Antoine

Forqueray, who was said to

possess a violent and

irascible temper, was compared

by his contemporaries solely

to his rival Marin Marais. As

a composer he succeeded in

applying to the gamba his

knowledge of contemporary

Italian violin music, thus

considerably extending the

limits of what had until then

been technically possible. If

we are to believe the Mercure

de France of August

1738, only Antoine Forqueray

himself and his son were

capable of playing Forqueray`s

very difficult Pièces da

Viole - the only

criticism, incidentally, which

the critic could add to

otherwise unmitigated praise.

The twenty-nine Pièces de

Viole by Antoine

Forqueray were published by

his son in 1747, two years

after his father's death, in a

version arranged by

Jean-Baptiste for two

different instrumentations:

one for viola da gamba with

basso continuo and one for

solo harpsichord.

Jean-Baptiste furnished the

edition with a figured bass

and added three works of his

own. To Jean-Baptiste, who

foresaw the inevitable decline

of the gamba brought about by

the ever-increasing popularity

of the violoncello, it seemed

only prudent to entrust his

father's music to the

harpsichord.

Just like François Couperin

and Jacques Duphly, Forqueray

immortalized colleagues

(Leclair) and wellknown

personalities in Parisian

society (La Tour) in his

harmonically rich character

pieces. Thus La Régerite

represents a portrait of Duke

Philippe of Orléans, himself a

pupil of Forqueray. It is a

noble and stately piece, full

of contrasts, here a passage

in “style luthe” and there a

flurry of repeated notes or

concatenations of triplets. In

La Tronchin, Forqueray

commemorates in musical form

one of the Duke's personal

physicians, Théodore Tronchin

(1709-1781). The latter, born

in Geneva, studied medicine

under Boerhaave in Leiden and

settled first in Amsterdam,

only some time later to return

to his native Geneva where his

good reputation as a doctor

brought him many invitations

to practise abroad: Only after

being persistently urged by

the Duke to do so, did

Tronchin move from Geneva to

Paris in 1766 where he came to

be regarded as a benefactor to

the poor and where he made

friends with Rousseau,

Diderot, Voltaire and Thomas.

La Angrave is one

of the three pieces by the

younger Forqueray. Light and

cheerful in character, it is

graceful and diaphanous yet

contains some bizarre

stravaganza effects. Following

his father's fearless and

resolute Rondeau La Eynaud,

Jean-Baptiste's La

Mourangis ou La Plissay,

an elegant chaconne with its

delightful middle section in

the minor key, is a

composition written in a style

more engaging than that of his

father.

La Maurella, a brusque

and fiery piece, is composed as

if in a single breath and

characterised by its dotted

rhythms and restless

chromaticism. The title evokes

associations with the French

game of hopscotch (“marelle”).

In La Clément, the

harpsichord player and

composer Charles-François

Clément (1720-1782) is

immortalized. Clément, born in

Provence, settled in Paris

where he wrote trio sonatas,

works for harpsichord,

cantatas and operas. His music

closely resembles the style of

Michel Corette, Gabriel

Guillemain and Jean-Joseph de

Mondonville. The Sarabande La

d'Aubonne is a serious

work full of sombre chords in

which the performer is

instructed by the composer to

invest his playing of the

piece with consummate taste

and sensitivity. Enriched with

emotionally charged

ornamentation, this work

contains precise instructions

on the correct sequence in

which the hands are to strike

the keys.

Le Riche La Pouplinière, a

passionate music-lover and

patron, was an energetic

Secretary of State and so

wealthy that he was able to

maintain one of the best

orchestras in Paris and to

engage musicians such as

Rameau, Johann Stamitz and

François-Joseph Gossec. He

purchased the Château de

Passy, where Rameau spent

every summer until 1753.

Forqueray was also a frequent

guest and apparently impressed

by the carillon there. Le

Carillon de Passy and La

Latour are two rondeaus

in G minor which, in ABA form,

belong together and were

played one after the other

without a break. The first

rondeau with its repeated

notes, recreates for us the

carillon at the Château de

Passy; and the second rondeau

surprises with its sudden

octave leaps and small

harmonic shocks.

In La Latour, Antoine

Forqueray has painted a

musical portrait of

Maurice-Quentin la Tour

(1704-1788) for us. La Tour

was a French painter famous

for his pastel portraits. One

of his pictures shows father

and son Forqueray together

with Michel de la Barre and

the Hotteterre brothers. La

Tour had a dubious reputation

on account of his often

eccentric appearance and his

candid and risqué remarks.

Once, when the flamboyant La

Tour wanted to go from St.

Cloud to Paris, he stripped

off his clothes and allowed

himself to be picked up by a

passing boat. Another time he

made an unbelievably great

fuss about not wanting to

paint a portrait of the

Marquise de Pompadour, Louis

XV's mistress. Eventually the

stubborn artist consented to

do it, but managed to extract

a promise from the Marquise

that they would not be

disturbed by anyone during the

sittings. One day the king

joined them. La Tour,

pretending not to have

recognized him, collected his

things and, before departing

bad-temperedly, cried,“You

said our sittings would not be

interrupted!” It is thanks to

the portraits painted by such

colourful artists as Forqueray

and La Tour that such a bright

light falls on one small piece

of the mosaic that was the

cultural life of Paris in the

18th century!

Clemens

Romijn

(Translation:

© 1992 John Constable)

|

|

|

|