|

|

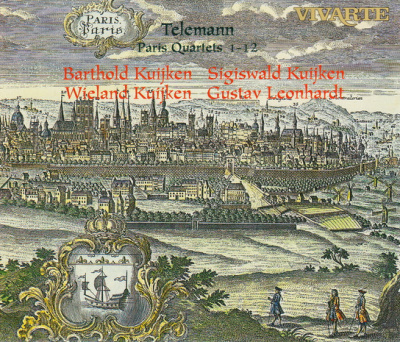

3 CDs

- S3K 63 115 - (p) 1997

|

|

PARIS QUARTETS 1-12

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Georg Philipp

TELEMANN (1681-1767) |

QUADRI

(Hamburg, 1730) |

|

|

|

|

No. 1: Concerto

Primo |

|

9' 57"

|

|

|

- Grave-Allegro (2' 40") · Largo

(0' 35") ·

Presto (2' 18")

· Largo (0' 35")

· Allegro (3' 43") |

|

|

1-1/5

|

|

No. 2: Concerto

Secondo |

|

11' 12" |

|

|

-

Allegro (3' 26")

· Affettuoso (3'

49") · Vivace (3' 52") |

|

|

1-6/8

|

|

No.

3: Sonata Prima

|

|

12' 03" |

|

|

-

Soave (3' 26")

· Allegro (2' 18")

· Andante (3' 54")

· Vivace (2' 21") |

|

|

1-9/12

|

|

No. 4: Sonata

Seconda |

|

12'

00"

|

|

|

-

Andante (3' 15")

· Allegro (2' 38")

· Largo (3' 26")

· Allegro (2' 36") |

|

|

1-13/16

|

|

No.

5: Première Suite

|

|

18'

38"

|

|

|

-

Prélude. Vitement (1'

27") · Rigaudon (2' 27") · Air (3' 38") ·

Replique (2' 29")

· Menuet I/II (5'

55") · Gigue (2' 37")

|

|

|

1-17/22

|

|

No. 6: Deuxième

Suite |

|

10' 26" |

|

|

-

Prélude. Gaiement (1'

17") · Air. Modérément (2' 37") ·

Réjouissance (1'

59") · Courante (2' 11") ·

Passepied (2' 21") |

|

|

1-23/271

|

|

NOUVEAUX

QUATUORS EN SIX SUITES (Paris,

1738)

|

|

|

|

|

No.

7: Premier Quatuor |

|

18' 03" |

|

|

-

Prélude. Vivement (2'

11") · Tendrement (2' 24") · Vite (3' 16") ·

Gaiement (4' 36")

· Modérément (2'

38") · Vite (2' 51")

|

|

|

2-1/6

|

|

No.

8: Deuxième Quatuor |

|

19' 48" |

|

|

-

Allègrement (2'

33") · Flatteusement (4' 05") ·

Légèrement (2' 14")

· Un peu vivement (3'

17") · Vite (1' 49") ·

Coulant (5' 43") |

|

|

2-7/12

|

|

No.

9: Troisième Quatuor |

|

22' 00" |

|

|

-

Prélude. Un peu vivement (2' 05") ·

Légèrement (3' 21")

· Fracieusement (2'

34") · Vite (2' 59") · Modéré

(4' 06") ·

Gai (1' 45")

· Lentement-Vite (5'

10")

|

|

|

2-13/19

|

|

No.

10: Quatrième Quatuor |

|

20' 23" |

|

|

-

Prélude. Vivement-Flatteusement (6' 12") ·

Coulant (2' 31")

· Gai (1' 48")

· Vite (1' 35")

· Triste (3' 26")

· Menuet. Modéré (4'

44") |

|

|

3-1/6

|

|

No.

11: Cinquième Quatuor |

|

18' 17" |

|

|

-

Prélude. Vivement (2'

07") · Gai (2'

06") · Modéré (5' 14") · Modéré

(4' 03") ·

Pas vite (1' 52")

· Un peu gai (2'

47") |

|

|

3-7/12

|

|

No.

12: Sixième Quatuor |

|

20' 23" |

|

|

-

Prélude. À discrétion-très vite (4' 49") · Gai (3' 08") · Vite (1' 27") ·

Gracieusement (3'

17") · Distrait (3' 11") · Modéré

(4' 41") |

|

|

3-13/18

|

|

|

|

|

|

Barthold

KUIJKEN, Flute

(Alains Weemaels, Brussels, 1985,

after I. H. Rottenburgh, Brussels,

c.1725)

|

|

Sigiswald

KUIJKEN, Violin

(Giovanni Grancino, Milan, c.1700)

|

|

| Wieland

KUIJKEN, Viola

da gamba (Nicolas Bertrand, Paris,

1705) |

|

| Gustav

LEONHARDT, Harpsichord

(Bruce Kennedy, Amsterdam, after

Mietke, Berlin, 1702/1704) - Pitch: a'

= 396 Hertz |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Doopsgezinde

Kerk, Haarlem (The Netherlands):

- 27/29 Novembre 1996

- 25/27 Febbraio 1997

- 4/6 Giugno 1997 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Recording supervisor |

|

Wolf

Erichson |

|

|

Recording

engineer / editing

|

|

Markus

Heiland (Tritonus) |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Nessuna |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Sony

"Vivarte" | LC 6868 | S3K 63 115 |

3 CDs - durata 74' 27" - 60' 00" -

59' 21" | (p) 1997 | DDD |

|

|

Cover Art

|

|

Johann

Georg Ringlin (1691-1761) "Paris

(France)", Kupferstich, c.1740,

after Friedrich Bernhard Werner

(1690-1778) |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

In

his autobiography published in

Johann Mattheson’s Grundlage

einer Ehren-Pforte

[Foundations For a Portal to

Honor] in 1740, the Hamburg

cantor Georg Philipp Telemann

wrote: “My long-postponed

journey to Paris, to which I

had been invited several years

earlier by Parisian virtuosi

who had found several of my

printed works suited to their

taste, began around Michaelmas

in 1737 and lasted eight

months. There, having received

a royal general privilege for

the next 20 years, I had

engraved new quartets sold by

subscription and six sonatas

entirely constructed from

melodic canons. The wonderful

way in which the quartets were

performed by Messrs. Blavet,

flurist, Guignon, violinist,

Forcroy [i.e. Forqueray]

junior, gambist, and Edouard,

violoncellist, would deserve a

better description than I can

here give you. Suffice it to

say that they made the ears of

both the royalty and the

citizenry attentive, and

earned for me a nearly general

honor in a short time, which

was accompanied by plenty of

courtesy.”

The works to which Telemann

refers are the Nouveaux

Quatuors en Six Suites on the

present recording, as well as

the popular set of canonic

duets for two melody

instruments without bass.

The quatuors were composed

with the leading professional

musicians in Paris in mind:

Michel Blavet (1700-1768) was

one of the finest flute

virtuosos of his day, as well

as being an accomplished

composer; Jean-Pierre Guignon

(1702-1774; originally named

Giovanni Pietro Ghignone) was

an Italian violin virtuoso in

the service of Louis XV;

Jean-Baptiste-Antoine

Forqueray (“le fils”;

1699-1782) was born into a

famous family of French

musicians (his father, the

renowned gambist Antoine

Forqueray, was said to have

abused his son out of jealousy

for his son's gifts as a

player of the viola da gamba);

while the identity of the

cellist Edouard remains

elusive. The part for the

harpsichord continuo was

probably taken by Telemann

himself.

The edition of the Nouveaux

Quatuors was published while

Telemann was still in Paris;

the title page lists as one

place where the work is

obtainable Telemann’s own

temporary residence in Paris

(“Chez l'auteur, vis à vis la

porte de l'hôtel du Temple”).

The work, as Telemann

indicates, was sold by

subscription, with the names

of the subscribers printed in

the violin part. The

subscription list is divided

geographically into “Noms des

Souscrivants de Paris et de

France” and “Noms des

Souscrivants des Pays

Étrangers." The latter

includes a “Mr. Bach, de

Leipzig.”

While the Nouveaux Quatuors

have rightfully come to be

called the “Paris” Quartets,

it is somewhat less clear

whether that sobriquet should

be applied as well to

Telemann’s first publication

devoted to the quartet, the

set of six Quadri also

included on this recording.

This set, unlike the Nouveaux

Quatuors, first appeared in

Hamburg, in 1730. As was his

habit, Telemann engraved the

plates for the publication

himself. The set was indeed

reissued in Paris in 1736 by

Le Clerc in a more elegantly

engraved edition. A notice

printed on the back of the

violin part claims “The

quartets of Telemann have met

with such universal approval

that it is believed it will

give the public pleasure to

present them in a new edition,

better engraved and on better

paper than all which have

appeared to the present.” Both

sets share the same scoring of

transverse flute, violin,

viola da gamba or violoncello

(two separate parts are

provided from which to chose),

and basso continuo. Further,

it is likely that the 1736

reprint of the Quadri was

among the “printed works” that

suited the taste of the Paris

virtuosi, prompting Telemann

to compose a second set for

Paris performance modeled upon

the first set. Unlike many of

Telemann’s Hamburg

publications, the Quadri -

just like the Nouveaux

Quatuors - were clearly

intended for professional

musicians.

In their brilliant mixture of

French, Italian, and even

Polish styles both sets of

quartets reflect an overriding

concern in Telemann's

instrumental publications of

the 1720s and ’30s: Which

national styles were

appropriate to the various

genres, and how could national

styles be combined? This

concern is also reflected in

many of J. S. Bach's works, as

well as Quantz's famous

Versuch of 1752, in which he

declares that “If one has the

necessary discernment to

choose the best from the

styles of different countries,

a mixed style results that,

without oversteppirig the

bounds of modesty, could well

be called the German style,

not only because the Germans

came upon it first, but

because it has already been

established at different

places in Germany for many

years, flourishes still, and

displeases in neither Italy

nor France, nor in other

countries.” The felicitous

combination of the two

principal national styles of

the early eighteenth century,

the French and the Italian,

had become a vogue in France

as well, where Italian genres

such as the sonata, concerto,

and cantata had taken hold and

had gained parity with the

traditional French genres of

the suite, ouverture, and air.

Blavet himself was a popular

composer of such mixed-style

pieces in France. It is no

wonder that Telemann’s two

sets of quatuors, with their

ingenious manifestations of

the mixed style, would find

favor in France as well as in

Germany.

The Quadri present a selection

of the principal Italian and

French genres: Telemann’s

original title page promises

“2. Concerti, 2. Balletti, 2.

Sonate.” In this case the

Italian “Balletti” refers to

French suites, the title page

adopting the Italian word for

“dances” to be consistent with

the Italian designation

“Quadri.” The order is

erroneous; the suites appear

last in the collection. Thus

the two principal Italian

instrumental genres as well as

the principal French

instrumental genre are

represented. The writing for

the solo instruments is both

virtuosic and idiomatic, and

shows Telemann’s capacity for

writing chamber music that

reflects the urbane wit of

galant conversation.

Especially within the concerti

and suites, however, a mixed

style predominates; the

sonatas are the most

conservative in presenting the

traditional imitative

polyphony of the Corellian

sonata da chiesa. The two

concertos each contain

movements imitating the

Vivaldian ritornello structure

(the Presto in the first

quartet, and the Allegro and

Vivace in the second quartet),

with other movements showing

Telemann’s galant adaptation

of the idioms of both Corelli

and Vivaldi. In the movements

in concerto structure, the

full ensemble generally

simulates the orchestra, while

one or more soloists present

brilliant figuration in the

solo passages. But the last

movement of the first quartet

shows the infiltration of the

mixed style into the concerto

by combining the

quintessentially French

structure of the rondeau with

the rhythm of the Italian

giga.

The two suites which close the

collection continue the idea

of the mixed style. Each

begins with a Prélude, which,

despite the French tempo

designations, is largely

Italian in style. After each

Prélude comes a series of

movements representing either

French court dances or the

pièces de caractère of the

Lullian opera and ballet (the

“Replique” in the first suite,

with its “replying” upper

parts being a particularly

charming example of the

latter). Especially to be

noted are the gigues, which

are closer to the Italian giga

(including the Air in the

second suite), and the novel

use of what C. P. E. Bach

would call “veränderte

Reprisen,” or “varied repeats,”

in the Courante in the same

suite. Here Telemann has fully

written out the repetitions of

both halves of the Courante,

with each repetition

presenting two simultaneous

versions of the melody: the

violin plays the original

courante tune, while the flute

plays an ornamented version of

the same line. In fact, the

flute version, with its rapid

sixteenth-notes figuration,

could be considered a more

“Italian” version of the

dance, in effect a corrente

instead of the more staid

French courante. This balances

as well the markedly Italian

accompaniment provided by the

viola da gamba or cello in the

first statement of each half.

While the Quadri present a

mixture of Italian and French

genres - the concerto, sonata,

and suite - the Nouveaux

Quatuors reflect their

thoroughly French milieu in

their series of purely French

suites. Each suite but the

second begins with a Prélude,

and is followed again by a

series of dances and pièces de

caractère, although only a

single movement bears an

actual dance designation (the

Menuet in the fourth suite).

The French style prevails in

the collection as a whole, but

a mixed style or even overtly

Italian style characterizes

the first movements. Three of

the suites (nos. 2, 4, and 5)

begin with full-fledged Italian

concerto movements; the solo

instrument is the flute in the

movement from the second suite

and the viola da gamba or

cello in the fourth suite,

while in the fifth suite the

solo role is taken by the

three melody instruments in

turn. Further, in the fourth

suite the opening movement is

repeated intact after the

second movement

(“Flatteusement”), simulating

the Vivaldian three-movement

concerto. The opening movement

of the first suite exemplifies

the Italian style with its

rapid arpeggiations over pedal

points, Lombardic rhythms, and

unisono ending.

The French style appears in

its purest form in some of the

dances, the rondeaux (note

especially the haunting

rondeau, with its subtle

blended colors, that appears

as the second movement of the

second suite), the pièces de

caractere (such as the

frenetic “Distrait” movement

in the final suite), and the

monumental chaconne (marked

“Modéré”) over a six-bar bass,

which closes the collection.

Some of the dance allusions

are presented in disguise; the

third movement, for example,

of the second suite

(“Lègérement”) turns out to be

a gigue, despite its somewhat

unconventional notation. Aside

from the chaconne and gigue,

the unlabelled dances include

the bourrée, gavotte, loure,

passepied, and menuet.

Telemann’s propensity for

stylistic and generic

experimentation is displayed

at its best in the movements

in the mixed style. The

opening Prélude of the final

suite (“À discretion - très

vite”) takes the form of the

French ouverture. Unlike the

Italianate preludes that open

the other quartets in the

collection, this quartet

begins with the traditional

first movement of the

orchestral suite. But after an

opening section in the dotted

rhythms typical of the

ouverture, the violin takes

over and plays virtuosic

figuration in the manner of the

Italian concerto. The same

stylistic juxtaposition occurs

when the movement returns to

the opening tempo following

the “très vite,” which itself

combines elements of the

French passepied with Italian

violin figuration.

The mixed style pervades other

movements as well. The fourth

movement (“Vite”) of the

fourth quartet presents two

national styles in

alternation: a French gigue

and an Italian giga. Two

movements (the final movements

of the second and fourth

suites) comprise sets of

variations in the Italian

manner, although their themes

are French. And a number of

movements combine French

ornaments, or agréments, with

Italianate passagework.

The twelve quartets in this

recording represent some of

the very finest music written

for chamber ensemble in the

first half of the 18th century.

Indeed, Telemann's quartets

were held up as models for

quartet writing in both France

and Germany, and contemporary

writers such as Scheibe and

Quann extolled them as

exemplary. Ultimately, the

quartet with basso continuo

was to give way to the quartet

without keyboard: the string

quartet. But in doing so it

gave up the variegated colors

that Telemann exploited so

brilliantly in the Quadri and

Nouveaux Quatuors.

1997

Jeanne Swack

|

|

|

|