|

|

1 LP -

SAWT 9424-B - (p) 1963

|

|

| 1 LP -

SAWT 9424-B - (p) 1963 |

|

| 1 LP -

6.41046 AS - (p) 1963 |

|

| 5 LPs -

SCA 25022-T/1-5 - (c) 1972 |

|

| 2 CDs -

8.35778 XD - (c) 1989 |

|

| CEMBALOKONZERTE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

BACH (1685-1750) |

Konzert

für zwei Cembali c-moll, BWV 1062 -

zwei Violinen, Viola und Continuo

|

I:

EM* | II: GL**

|

|

14' 42" |

|

|

-

(Allegro)

|

|

3' 44" |

|

A1

|

|

- Andante

|

|

6' 07" |

|

A2

|

|

-

Allegro assai

|

|

4' 51" |

|

A3 |

|

Konzert

für zwei Cembali c-moll, BWV 1060 -

zwei Violinen, Viola und Continuo |

I:

GL** | II: EM *

|

|

14' 02" |

|

|

-

Allegro

|

|

5' 02" |

|

A4 |

|

-

Adagio |

|

5' 09" |

|

B1 |

|

-

Allegro

|

|

3' 51" |

|

B2 |

|

Konzert

für vier Cembali a-moll, BWV 1065 -

zwei Violinen, Viola und Continuo |

I:

EM* | II: GL*** | III: JvW**** | IV:

AU**

|

|

10' 17" |

|

|

-

(Allegro) |

|

4' 35" |

|

B3 |

|

-

Largo |

|

2' 10" |

|

B4 |

|

-

Allegro

|

|

3' 32" |

|

B5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

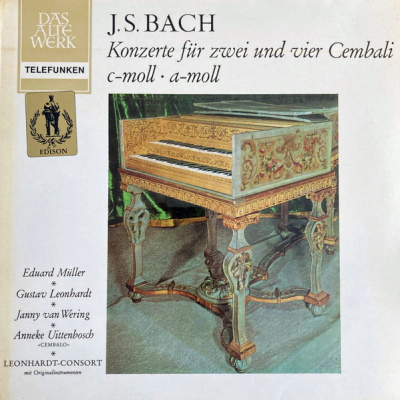

Eduard

MÜLLER, Cembalo

Gustav LEONHARDT, Cembalo

Janny van WERING, Cembalo

Anneke UITTENBOSCH, Cembalo

|

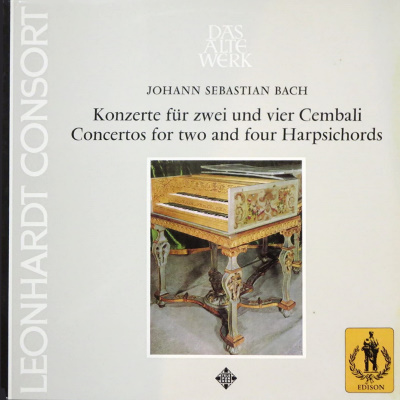

DAS

LEONHARDT-CONSORT

- Marie Leonhardt, Antoinette van den

Hombergh, Violine

- Wim ten Have, Viola (BWV 1062, 1065)

- Lodewijk de Boer, Viola (BWV 1060)

- Dijck Koster, Violoncello

- Fred Nijenhuis, Baß

|

Instrumente:

- Cembalo (R. Rück, nach C. A. Gräbner,

Dresden, 1782, kopiert) *

- Cembalo (M. Skowroneck, nach J. D.

Dulcken, Antwerpen, kopiert) **

- Cembalo (J. & A. Kirckman, London,

1755) ***

- Cembalo (J. C. Neupert, 1932) ****

- Violine (Jakob Stainer, 1676)

- Violine (Klotz, 18. Jahrh.)

- Viola (Giovanni Tononi, 17. Jahrh.)

- Viola (deutsch, 18. Jahrh.)

- Violoncello (Giovanni Battista [II]

Guadagnini, 1749

- Kontrabaß (deutsch, 18. Jahrh.)

Alle Instrumente in Barockmensur

Stimmung ein Halbton unter normal

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Amsterdam (Holland) -

22/27 Ottobre 1962

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Telefunken "Das Alte

Werk" | SAWT 9424-B (Stereo) - AWT

9424-C (Mono) | 1 LP - durata 39'

01" | (p) 1963 | ANA

Telefunken "Das Alte Werk" | SAWT

9424-B | 1 LP durata 39' 01" | (p)

1963 | ANA | Riedizione

Telefunken

"Das Alte Werk" | 6.41046 AS | 1

LP - durata 39' 01" | (p) 1963 |

ANA | Riedizione

Telefunken "Das Alte Werk" | SCA

25022-T/1-5 | 5 LPs - durata

212' 39" | (c) 1972 | ANA | (Sämtliche

Cembalokonzerte)

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Teldec Classics |

LC 3706 | 8.35778 XD | 3 CDs -

durata 76' 42" - 72' 00" - 63'

57" | (c) 1989 | ADD |

(Sämtliche Cembalokonzerte) |

|

|

Cover

|

|

- |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Bach's

harpsichord concertos were

composed at Leipzig where,

beside his appointment as

cantor at the St. Thomas

School, from 1729 to 1736 he

had taken on the direction

of the Telemann Music

Society and of the Collegium

Musicum of the University.

He must have had excellent

keyboard performers at his

disposal, for apart from the

fact that he liked to play

the leading harpsichord part

himself, he expressed his

predeliction for this

keyboard instrument during

those years in six concertos

for more than one

harpsichord. In his own

family his sons Friedemann

and Philipp Emanuel had also

matured into good keyboard

players, so that he could

say proudly: “But altogether

they are born musicians, and

I can assure you that I can

already form a concert, both

vocal and instrumental, with

my family”. This is still

proved to us today by the “5

keyboard instruments, 2

violins, 3 violas, 2 ‘cellos

and 1 gamba“ that have come

down to us as part of Bach's

possessions.

Bach wrote seven concertos

for one harpsichord, three

for two, two for three and

one for four harpsichords,

letting their dominating

solo parts be accompanied or

supplemented by a string

orchestra. In order to

prepare them he returned to

the instrumental concertos

he had written during his

years as a conductor at

Köthen, and rewrote them as

harpsichord concertos. The

parts of the former solo

instruments were retained

note for note, appearing in

the right-hand part for the

harpsichord, while the left

hand was given a second part

that reinforces the musical

argument. Each of these

harpsichord concertos has

three movements. The first

and third movements are full

of hearty, joyful

music-making. The orchestra

begins, in lively spirit,

then giving the harpsichord

opportunity to develop its

theme. The soloists

alternate with one another,

and as in the ritornello of

a rondo the orchestra takes

up its theme again and again

in between, thus leading the

movement to its conclusion

too. The second movement is

always more contemplative.

The surging tutti here comes

to rest. The soloists play

in duet with fervent

feeling, imitating one

another or exchanging parts

while the orchestra only

accompanies them.

The refashioning of existing

instrumental works for the

more abstract and abundant

sound of the harpsichord

shows us particularly

clearly Bach's mastery in

rationally arranging the

compositions for their new

purpose and, in spite of the

increased density of

texture, in preserving the

clarity and intelligibility

of the musical thought. For

these works are intended for

playing by music lovers in

the first place, and were

performed not only in the

family circle but also in

coffee houses and gardens by

the students, for the

entertainment and pleasure

of the guests. The short,

concentrated themes pass

through the works in a

variety of guises, and as a

result of their constant

reappearance they remain

familiar to the ear and

retain the listener's

attention.

The Harpsichord Concerto in

C minor (Bachwerke 1062) was

written in 1736, and has

evolved from the Concerto in

D minor for two violins

composed at Köthen in 1720.

As mentioned above, the two

solo violin parts appear in

the right hand of the two

harpsichord parts, while

Bach otherwise adapts the

work to suit the more arging

character of the

harpsichord's tone.

The Concerto in C minor (BW

1060) was written in 1730,

and has been adapted from

the Köthen Concerto for

Violin and Oboe in D minor.

It is distinguished by its

gay, energetic music-making

and an Adagio consisting of

a sensitive duet between the

two harpsichords played

throughout with only a

pizzicato accompaniment.

The Concerto in A minor (BW

1065) for Four Harpsichords

dating from 1733 is an

arrangement of the Concerto

in B minor for Four Violins

and String Orchestra by

Antonio Vivaldi, whose works

Bach liked so much that he

already made keyboard

reductions and arrangements

of them early on in his

career. The enjoyment of

light-hearted music-making

with which the Vivaldi work

is pervaded also determines

the manner in which it has

been adapted for the

harpsichord, although Bach's

supreme art has increased

the music’s intensity and

left its unmistakeable stamp

on the work. It has acquired

a larger and more powerful

character because a

particular tension has been

built into it, working up to

a powerful dominant tension

in E major in the Largo and

not regaining the A minor

basis of the whole work

until the third movement,

which then leads the work to

a confident conclusion.

Otto

v. Irmer

|

|

|

|