|

|

1 LP -

SAWT 9497-B - (p) 1966

|

|

| 1 LP -

6.41071 AS (SAWT 9497-B) - (p) 1966 |

|

| 1 CD -

3984-21765-2 - (c) 1998 |

|

| PIÈCES DE

CLAVECIN EN SONATES - Oeuvre 3, Paris

etwa 1734 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Jean-Joseph

Cassanéa de MONDONVILLE (1711-1772) |

Sonate

Nr. 1 g-moll |

|

6' 45" |

A1 |

|

-

(Ouverture · Aria · Giga)

|

|

|

|

|

Sonate

Nr. 3 B-dur |

|

6' 22" |

A2

|

|

-

(Allegro · Aria · Allegro) |

|

|

|

|

Sonate Nr. 4 C-dur |

|

11' 00" |

A3 |

|

-

(Allegro · Aria · Giga) |

|

|

|

|

Sonate

Nr. 5 G-dur |

|

5' 42" |

B1 |

|

-

(Allegro · Aria · Allegro) |

|

|

|

|

Sonate

Nr. 2 F-dur

|

|

5' 43" |

B2 |

|

-

(Allegro · Aria · Giga) |

|

|

|

|

Sonate

Nr. 6 A-dur |

|

11' 00" |

B3 |

|

-

(Concerto · Larghetto · Giga) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lars

FRYDÉN, Barock violine

(Alexander Kennedy, London 1767)

Gustav LEONHARDT, Cembalo

(Jacobus Kirckman, London 1766

Beide Instrumente in Barockmensur.

Stimmung ein Halbton unter normal

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

(luogo di

registrazione non indicato) - 1966

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

-

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Telefunken "Das Alte

Werk" | SAWT 9497-B (Stereo) - AWT

9497-C (Mono) | 1 LP - durata 47'

06" | (p) 1966 | ANA

Telefunken

"Das Alte Werk" | 6.41071 AS

(SAWT 9497-B) | 1 LP - durata

47' 06" | (p) 1966 | ANA |

Riedizione |

|

-2

|

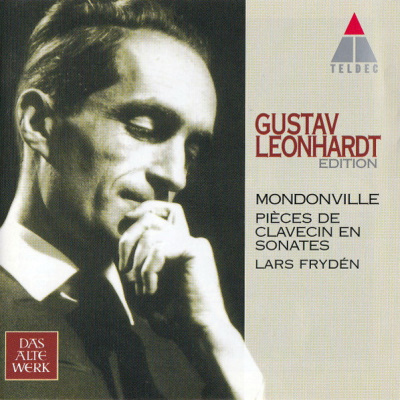

Edizione CD |

|

Teldec Classics |

LC 6019 | 3984-21765-2 | 1 CD -

durata 47' 06" | (c) 1998 | ADD

|

|

|

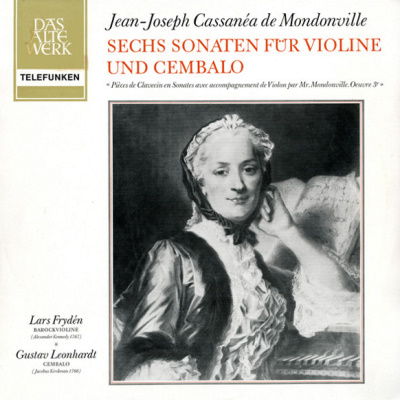

Cover

|

|

"Md. de Mondonville

am Klavier", Gemälde von Maurice

Quentin de la Tour.

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Among the

composers who, through their

performing and writing, won

a leading place for the

violin alongside the

harpsichord in French

chamber music of the first

halft of the 18th

century, Jean Joseph

Cassanéa de

Mondonville occupies

an honourable place. Born at

Narbonne in 1711, he already

made his voice heard in

Paris in 1733 with his

"Sonates pour le Violon Op.

1", and in 1734 he made his

début as a violinist "d'une

manière très brillante" at

the Concert Spirituel, the

trend-setting public concert

of the metropolis. He also

won success very soon as a

composer of church music. In

1738 the management of the

Concerts Spirituels offered

him a fixed annual salary of

1200 livres "pour ses motets

et pour jouer le Violon,"

and he performed together

with his most important

rivals, the violin virtuosi

and composers Guignon and

Guillemain. In 1748 he

joined the management of the

Concerts Spirituels, he was

their organizer and

conductor 1755-1762 and, in

addition, "Administrator" of

the Court Orchestra

1745-1758 - all in all, a

key figure for decades in

Parisian musicall life and a

celebrated and

self-confident master, also

in the fields of opera and

church music.

Mondonville's output

faithfully reflects the

changing fashions of

Parisian musical life

between 1730 and 1770. At

the beginning of his career

there stand, alongside some

lost violon concertos, the

great, partly pioneering

chamber music works: the

Violin Sonatas Op. 1 (1733),

the Trio Sonatas Op. 2

(1734), the "Pièces de

Clavecin en Sonates avec

Accompagnement de Violon Op.

3" (ca. 1734), the Violin

Sonatas with Continuo Op. 4

(ca. 1735) and the "Pièces

de Clavecin avec Voix ou

Violon Op. 5" (1748). After

this, Mondonville's chamber

music composition ceases

abruptly; instead, church

music occupies the central

place in his activities

until well into the fifties,

and in the degree to which

the opera held Paris in

suspense with the impending

revolution of the "tragédie

lyrique" through Gluck,

composition for the stage

also came to the fore. In

the last decades of his

life, Mondonville wrote

exclusively for the Paris

opera.

The decisive historical and

artistic achievements of

this composer are, however,

not his operas but his early

chamber music works, above

all the violin sonatas. It

was they that established

his fame in Paris, being

played, listened to and

discussed at all the focal

points of the capital's

musical life. Mondonville at

once found the idiom best

suited to the Parisian

cultivation of chamber

music, with its combination

of social brilliance,

cultured entertainment and

soundness of knowledge. The

Violin Sonatas Op. 1 already

display his characteristic

style - the easy, playful

and elegant blend of

graceful rococo melody,

soundness and delicacy of

technique, select, subtle

and distinctively surprising

harmony and brilliant

writing for the violin. In

the later works an

experimental spirit and a

delight in technical

problems come more into the

foreground without

disturbing the charm of the

general impression. Here, as

everywhere else in

mondonville's works, the

spirit of 18th century

France has assumed musical

shape in the most graceful

manner, and it is this,

independently of any

historical signifcance of

the works, that lends them

their undimished freshness

and attractiveness.

The six "Pièces en Sonates"

on our record (Op. 3, ca.

1734) mark the beginning of

a new type of composition in

France: the "classical"

piano-violin sonata in which

the two instruments play

together on an equal footing

and an 'obligato' basis.

They differ from Bach's

violin sonatas in the free

part-writing and

'concertante' character of

their structure, from the

earlier baroque violin

sonata in freeing themselves

from the continuo and

transferring the forms and

techniques of the French

harpsichord piece to the

ensemble sonata. In this

combination of violin sonata

and harpsichord piece,

Mondonville has thoroughly

exploited all the possible

combinations, shadings and

instrumental techniques that

there was hardly anything

left for his successors to

do. This is all the more

true in that his blending of

types corresponds

stylistically to an equally

logical combination of

French and Italian idioms

and forms from the

miniature-like Parisian

clavecin-pièce to the

Italian concerto à la

Vivaldi. around 1734

Mondonville's sonatas stand

solitary in a fertile but

still fallow field.

At a first glance, their

form is consistently that of

an Italian concerto:

Allegro, aria und Allegro,

the latter usually

designated as Giga. However,

behind the neutral term

Aria, there hide a wide

variety of slow movement

models, and the first and

last sonatas are thrown into

relief as "French" and

"Italian" prototypes: the

first by a French overture

as its opening movement, the

last as an Italian concerto

with "tutti" and "soli."

Thus the elements

ingeniously and

entertainingly blended in

the rest of the sonatas of

the series are introduced

programmatically at the

beginning and the end. The

wit, elegance and

cosmopolitan spirit of the

early "dixhuitième" have

seldom entered works of

musical art more

authentically.

Ludwig

Finscher

|

|

|

|