|

|

1 LP -

SAWT 9490-A - (p) 1967

|

|

| 1 CD -

0630-12326-2 - (c) 1996 |

|

| DOPPELKONZERTE

DER BACH-SÖHNE AUF ORIGINALINSTRUMENTEN

UM 1750-1788 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Carl Philipp

Emanuel BACH (1714-1788) |

Doppelkonzert

für Cembalo, Hammerflügel, 2 Flöten, 2

Hörner, Streicher und Baß Es-dur, Wq

47 (H 479)

|

|

|

16' 41" |

|

|

-

Allegro di molto

|

|

6' 58" |

|

A1

|

|

-

Larghetto |

|

5' 09" |

|

A2

|

|

-

Presto |

|

4' 34" |

|

A3

|

| Johann Christian BACH

(1735-1782)

|

Doppelkonzert

(Sinfonia concertante) für Oboe,

Violoncello, 2 Oboe, 2 Hörner, Streicher

und B.c. F-dur, W C38 |

* |

|

11' 00" |

|

|

-

Allegro |

|

7' 36" |

|

A4

|

|

-

Tempo di Minuetto |

|

3' 24" |

|

B1

|

| Wilhelm Friedemann

BACH (1710-1784)

|

Doppelkonzert für 2 Cembali, 2

Trompeten, 2 Hörner, Pauken, Streicher

und Baß Es-dur, Fk 46 |

* |

|

21' 53" |

|

|

- Un

poco Allegro |

|

11' 21" |

|

B2

|

|

-

Cantabile |

|

2' 54" |

|

B3

|

|

-

Vivace |

|

7' 38" |

|

B4

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

First modern performance *

All instruments in baroque dimensions,

pitch about a semitone below normal.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anneke

Uittenbosch, Alan Curtis, Cembalo

Jean Antonietti, Hammerflügel

Frans Brüggen, Frans Vester,

Traversflöte

Carol u. Thomas Holden, Naturhorn

Jürg Schaeftlein, Karl Gruber,

Barockoboe

Anner Bylsma, Barockcello

Hermann Shober, Josef Spindler,

Trompete

|

LEONHARDT-CONSORT

Amsterdan und CONCENTUS MUSICUS

Wien

- Alice Harnoncourt, Marie Leonhardt,

Antoinette van den Homberg, Walter Pfeiffer,

Peter Schoberwalter, Violine

- Wim ten Have, Lodowijk de Boer, Viola

- Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Dijck Koster, Violoncello

- Fred Nijenhuis, Eduard Hruza, Violone

- Karel van de Grient, Pauken

Gustav LEONHARDT, Dirigent

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Hervormde Kerk,

Bennebroek (Holland) - 16/18,

20/21 Giugno 1966

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Telefunken "Das Alte

Werk" | SAWT 9490-A | 1 LP -

durata 49' 36" | (p) 1967 | ANA

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Teldec Classics |

LC 6019 | 0630-12326-2 | 1 CD -

durata 49' 36" | (c) 1996 | ADD

|

|

|

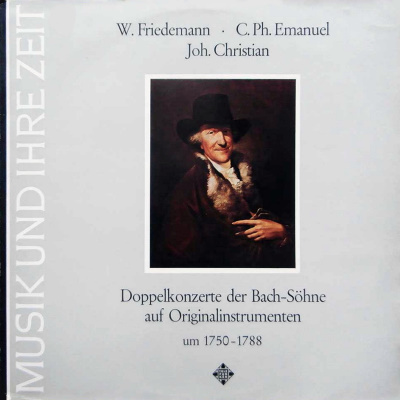

Cover

|

|

Wilhelm Friedemann

Bach (1710-1784), J. S. Bach's

eldest son, painting by Wilhelm

Wltsch, Museum of the Town of

Halle.

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Carl Philipp

Emanuel Bach’s Double

Concerto for Harpsichord and

“Hammerklavier” is, if the

date 1788 attributed to it

is correct, the latest of

the three works on this

record. In any case it is

the most original. Bach’s

second son, a lifelong

experimenter, has intervened

here - in the year of his

death - in a process that

must have occupied his

attention very much as the

greatest “expressive” master

of the harpsichord and

clavichord: the displacement

of the “old” harpsichord by

the “modern” “Hammerklavier”

(long decided by 1788), and

has easily come to terms

with the situation. The

solution he offers is both

conservative and

revolutionary at the same

time. Once again the

harpsichord is used quite

naturally as a solo

instrument (Mozart’s great

piano concertos were already

written, but for the last,

in 1788), but it is

contrasted with its

victorious rival in such a

manner that the

soundcharacter of both

instruments and their

possibilities of colour are

effectively played off

against one another. The

principle of “concertare”

has been transferred from a

contest between tutti and

solo to a rivalry between

two principles of sound

production and playing. It

is thus extended in a most

ingenious fashion into a

reflection of the historical

competition between the two

instruments, the harpsichord

having more to say in the

first movement, the piano

displaying its greater

melodiousness and the

harpsichord its greater

agility in the second and

the piano not finally

“setting the fashion” until

the Finale. That the work

falls between the epochs

also reveals itself in the

basic character of its three

movements: in the nervously

resilient rhythms of the

“Hamburg Bach”, the abrupt

dynamic contrasts and the

amazing harmonic changes, as

well as in the already quite

classical, free and

colourful treatment of the

wind, in the adventurous

virtuosity of the outer

movements and in the

“cantilena” of the

Larghetto, noble yet

continually divided into

finely-chiselled

ornamentation.

Johann Christian Bach’s

Sinfonia Concertante,

probably written during the

composer’s later years in

London (ca. 1770-1781), is a

genuine “concertante”

symphony after the Parisian

pattern, but completely

filled with the melodic

grace and gentle sensibility

of this most “galant” of

composers. Like many

concertos, symphonies and

chamber music works of the

pre-classical period, this

work has only two movements

- a large-scale Allegro in

free sonata form and an

Italianate Tempo di

Minuetto. Both derive their

substance from an

ingratiatingly song-like and

graceful melodic style that

is essentially highly

conventional. But the manner

in which a concerto movement

of the greatest elegance and

finesse of form is built out

of these fashionable turns

of phrase, how a delicately

rustic mood a la Watteau is

distilled from the Italian

minuet character constitutes

the secret and the magic of

the “London Bach”, who

realized more truly than any

other composer of the 18th

century the ideal (by no

means to be despised) of a

social art refined to the

utmost. A greater contrast

in the music of this century

could hardly be imagined

than that existing between

this work and the Double

Concerto of the eldest and

most unhappy of Bach’s sons,

Wilhelm Friedemann, which

was presumably written

around 1750-60. It is

modelled on concertos by the

father in that it is written

for two solo harpsichords,

and on the latter’s C major

Concerto in that the middle

movement is a duet for the

solo instruments without

orchestra. Otherwise there

is very little that recalls

his father’s style - most

readily perhaps the heavy

and resplendent orchestral

writing with trumpets, horns

and timpani, which is still

treated entriely in the

manner of a baroque tutti.

Also baroque is the

character of the first

movement with its gloomy

solemnity, its “sighing”

suspensions and its brief

chordal interjections by the

tutti into the big, virtuoso

solo passages; the harmony,

on the other hand is

strongly reminiscent of the

style of his younger brother

Carl Philipp Emanuel in its

surprise effects. In spite

of its key of C minor, the

3/8 Cantablile with its

rapturous parallel thirds

and sixths, written in three

parts throughout, is more

genial in its effect than

this mighty first movement

in the peculiar chiaroscuro

colouring which had already

struck his contemporaries in

Friedemann’s style. The

Finale combines the baroque

sound of the first movement

with a thematic material

that is already quite early

classical, almost

reminiscent of early Haydn,

and in typical finale

character. Even so, it is

not yet able to find the

carefree finale spirit, the

“final dance” character of

the early classical period;

the gloomy, frequently

fantastic-bizarre quality

that dominated Wilhelm

Friedemann’s life just as

much as his work is also

clearly in evidence here.

Ludwig

Finscher

Wilhelm

Friedemann, Carl Philipp

Emanuel and Johann

Christian Bach

Our

image of Wilhelm

Friedemann Bach, the

eldest son of Johann

Sebastian, has been

distorted through legends

about his allegedly

dissolute life, drunkenness

and. forgeries. The fact

that these legends, spread

once upon a time by

influential writers on

music, have asserted

themselves for so long, and

that their influence can

still be felt today through

Emil Brachvogel’s novel

(1858) is largely due to a

lack of information dating

from Friedemann’s own

lifetime, as a result of

which important events are

shrouded in darkness.

Wilhelm Friedemann was

undoubtedly the most

brilliant of the older

Bach’s sons. Born on the

22nd November 1710 in

Weimar, he received a

thorough musical training

from his father, this being

documented by the Little

Keyboard Book, begun in

Cöthen on the 22nd January

Ao. 1720, written

specially for Friedemann by

his father. After attending

St. Thomas's School in

Leipzig, where the family

had settled in 1723,

Friedemann studied various

subjects for four years at

Leipzig University, as was

usual for an educated

musician in those days, his

favourite subject being

mathematics. In 1733 he was

appointed organist at St.

Sophia's “Church in Dresden.

His duties were but few, and

so he had plenty of time to

gather artistic stimuli in

this cosmopolitan city,

through the company of such

composers as J. A. Hasse and

through access to the music

of the court, for which he

wrote a large number of

instrumental works. After

thirteen years Friedemann

left Dresden in 1746, and

took up the post of organist

at the “Liebfrauenkirche” in

Halle, a post which Johann

Sebastian had turned down

thirty years previously. Far

more extensive tasks awaited

Friedemann in Halle; not

only did he have to play the

organ, but also to be

responsible for the entire

church music. Halle also

meant a complete

readjustment for the artist

in another respect: from the

capital city, open to every

artistic stimulus,

Friedemann came to the

former centre of pietism,

where the attitude towards

church music was, at bottom,

hostile. Friction was

therefore bound to arise

between the artist, inclined

towards eccentricity and

willfulness, and the church

authorities to whom he was

responsible. It eventually

led to his resigning from

his post in 1764; the actual

reason is not known to us.

Without ever occupying a

permanent position again, he

led from then onward an

unsettled, restless life

that took him to Brunswick

in 1770 and finally to

Berlin in 1774, where he

died in 1784, leaving his

wife and daughter in the

greatest poverty. He was

hampered by his inability to

strike a balance between his

artistry and bourgeois life,

and suffered the same fate

as the poets of the “Sturm

und Drang” (storm and

stress) period - the age of

geniuses, which was then

just dawning. The idea of

life as a free artist was

still incapable of

realization at that time.

Even so, Friedemann remained

in high esteem as an

organist and improvisor; in

his obituary in Cramer's

Magazine in 1784 we find the

words: “Germany has lost in

him its leading organist,

and the entire musical world

a man whose loss cannot be

made good.”

"I, Carl Philipp Emanuel

Bach, was born at

Weimar in March 1714. My

late father was Johann

Sebastian, conductor at

various courts and finally

Musical Director in

Leipzig... After completing

my school education at St.

Thoma's School, Leipzig, I

studied law, both in Leipzig

and, later, in Frankfurt on

the Oder, in which latter

place I conducted and

composed for both a musical

‘academy’ and all public

musical performances at

festivities that fell within

that period. In composition

and in keyboard playing I

never had any other teacher

than my father. When I ended

my academic years in 1738

and went to Berlin, I had a

favourable opportunity of

conducting a young gentleman

to foreign countries; an

unexpected gracious

appointment by the Crown

Prince of Prussia at that

time, now the king, to

Ruppin caused my intended

journey to be cancelled.

Certain circumstances,

however, resulted in my not

being able to enter formally

into the service of His

Prussian Majesty until his

accession in 1740... From

this time until November

1767 I was continuously in

the service of Prussia,

notwithstanding the

opportunity I had a few

times of taking up

favourable appointments

elsewhere ... In 1767 I was

offered the post of Musical

Director in Hamburg in place

of the late conductor Herr

Telemann! ... My Prussian

duties never left me

sufficient time to travel to

foreign countries ... This

lack of journeys abroad

would have been most

detrimental to me in my

profession had I not had the

particular good fortune from

my youth onward of hearing

in the vicinity the most

excellent in all kinds of

music, and of making the

acquaintance of very many

masters of the first

order...” This quotation is

from the biographical sketch

that Philipp Emanuel

provided in 1773 for the

German translation of

Burney's Diary of a

Musical Journey. Of

Johann Sebastian’s sons, it

was he who exercised the

most important influence on

the classical period, being

revered by Haydn (“Emanuel

is the father, we are his

children”) and taken

as a model by Beethoven.

Philipp Emanuel became

famous just as much through

his clavichord playing as

through his didactic work Treatise

on the True Manner of

Playing Keyboard

Instruments (1753) and

through his keyboard

compositions. In contrast to

his elder brother

Friedemann, he was an adroit

man of the world and an

astute businessman who

partly published his own

compositions. He was highly

educated, enjoyed the

company of Lessing,

Klopstock and Matthias

Claudius and corresponded on

musical matters with

Diderot. Philipp Emanuel

died in Hamburg on the 14th

December 1788.

Johann Christian Bach,

born on the 5th September

1735 in Leipzig as the

youngest son of Johann

Sebastian, was the most

modern of the brothers in

his composition. His

significance for the new

style was long

underestimated, and he was

considered playful, trifling

and superficial. He

particularly exercised a

profound and lasting

influence on Mozart, who

came to London, where Bach

had just settled, as a child

prodigy in 1764.

The life of Johann Christian

diverges fundamentally from

that of the other Bachs;

indeed it could be called

completely un-Bachian.

Already as a boy, with the

scanty financial

circumstances of his

parents’ home before his

eyes, he wished to achieve

fame and wealth as a

musician, and paved the way

for himself towards this

goal in every thinkable

manner. After the death of

his father in 1750, he went

to Berlin at the age of

fifteen, to his half-brother

Philipp Emanuel, who trained

him as an excellent keyboard

player. At the same time he

received stimulation from

the Berlin Opera, where the

Italian style was cultivated

by Graun and Hasse. Probably

in 1756, he travelled to

Italy with an Italian prima

donna, in order to study

opera himself at its source.

A noble patron enabled him

to study with Padre Martini

in Bologna, who was later to

teach the young Mozart as

well. By changing over to

the Catholic faith, Johann

Christian, who now called

himself Giovanni Bach,

became appointed organist at

Milan Cathedral in 1760.

Soon after this he wrote his

first operas for Turin and

Naples, through which he

immediately achieved fame.

In the summer of 1762,

however, he was already

turning his steps towards

London, where he presented

operas as the Saxon

Music-Master John Bach,

and was granted the position

of Royal Music-Master to the

young queen. London was then

a particular centre of

attraction to musicians, for

a rich musical life had

prevailed there since

Handel’s time. Bach became

the acknowledged favourite

of the London public,

composing work after work

with ease and leading an

extremely luxurious life. A

royal decree refers to him

as the “loyal and

well-beloved Bach”.

Characteristic of his

attitude to his own works is

the remark in the autograph

of his B flat major Piano

Concerto: “How have I

made this concerto, isn’t

that fine?” In the

years 1772-1779 Bach made

journeys to Mannheim, the

centre of the new trend in

style, and to Paris, and

scored great successes there

with new operas. Then,

however, his. fortunes began

to decline. Enslaved by

drink and deeply in debt, he

died in London already on

the 1st January 1782.

Hans-Christian

Müller

|

|

|

|