|

|

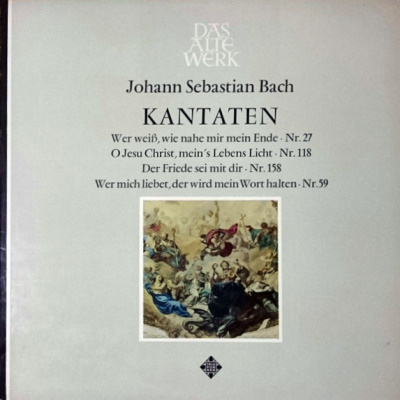

1 LP -

SAWT 9489-B - (p) 1968

|

|

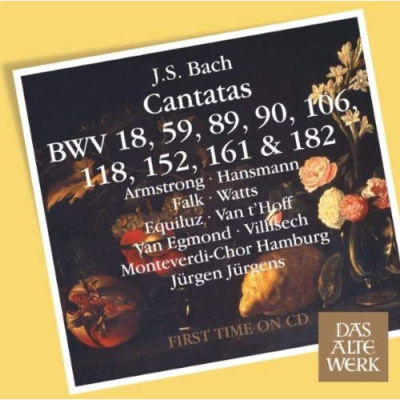

| 2 CDs -

2564-69599-2 - (c) 2008 |

|

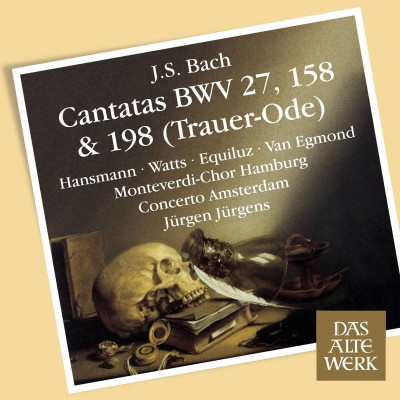

| 1 CD -

2564-64763-2 - (c) 2013 |

|

KANTATEN

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

BACH (1685-1750) |

Kantate

"Wer weiß, wie nahe mir mein Ende",

BWV 27 - Kantate am sechzehnten Sonntag

nach Trinitatis (Dominica 16 post

Trinitatis) |

|

17' 09" |

A1 |

|

für

Soli: Sopran, Alt, Tenor, Baß; Chor;

Oboe I/II; Oboe da caccia; Tromba; Orgel

(obligat); Violine I/II; Viola; Continuo |

|

|

|

|

- Chor: "Wer weiß, wie nahe mir

mein Endel"

|

4' 38" |

|

|

|

-

Recitativo (Tenor): "Mein Leben hat kein

ander Ziel"

|

0' 51" |

|

|

|

-

Aria (Alt): "Willkommen! will ich sagen"

|

5' 35" |

|

|

|

-

Recitativo (Sopran): "Ach, wer doch schon

im Himmel wär!" |

0' 59" |

|

|

|

-

Aria (Baß): "Gute Nacht, du Weltgetümmel!" |

3' 50" |

|

|

|

-

Choral (Chor): "Welt ade! ich bin dein

müde" |

1' 10" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"O

Jesu Christ, mein's Lebens Licht",

BWV 118 |

|

|

|

|

Motette

zur Trauerfeier für den Reichsgrafen und

Gouverneur der Stadt Leipzig Joachim

Friedrich von Flemming (gest. 11. 1. 1740) |

|

3' 45" |

A2 |

|

für

Chor; Lituo (Horn) I/II; Cornetto (Zink

oder hohe Trompete); Trombone (Posaune)

I/II/III; Orgel |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kantate

"Der Friede sei mit dir", BWV 158

|

|

11' 34" |

B1 |

|

Kantate

am Fest Mariä Reinigung oder am dritten

Osterfesttag (Festo Purificationis Mariae,

Feria 3 Paschatos) |

|

|

|

|

für

Solo-Baß; Chor; Oboe; Violine solo;

Continuo |

|

|

|

|

-

Recitativo (Baß): "Der Friede sei mit dir" |

1' 56" |

|

|

|

-

Aria - Choral (Baß, Sopran): "Welt ade!

ich bin dei müde" |

6' 34" |

|

|

|

-

Recitativo (Baß): "Nun Herr, regiere

meinem Sinn" |

1' 44" |

|

|

|

-

Choral (Chor): "Hier ist das rechte

Osterlamm" |

1' 17" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kantate

"Wer mich liebet, der wird mein Wort

halten", BWV 59 - Kantate zum ersten

Pfingstfesttag (Feria 1 Pentecostes)

|

|

10' 44" |

B2 |

|

für

Soli: Sopran, Baß; Chor*; Tromba I/II;

Timpani; Violine I/II; Viola; Continuo

(Cello, Baß, Orgel) |

|

|

|

|

-

Duett (Sopran, Baß): "Wer mich liebet, der

wird mein Wort halten" |

3' 55" |

|

|

|

-

Recitativo (Sopran): "O was sind das vor

Ehren" |

2' 06" |

|

|

|

-

Choral (Chor): "Komm, heiliger Geist, Herr

Gott!" |

1' 48" |

|

|

|

-

Aria (Baß): "Die Welt mit allen

Königreichen" |

2' 55" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rotraud Hansmann, Sopran

Helen

Watts, Alt

Kurt Equiluz, Tenor

Max van Egmond, Baß

MONTEVERDI-CHOR, HAMBURG

/ Jürgen Jürgens, Leitung

AMSTERDAMER KANTOREI (BWV 59)

Lilian Lagaay, Ad Mater, Oboe

Ad Mater, Oboe da caccia

Wim Groot, Fred Grin, Trompete

Hermann Baumann, Adriaan van

Woudenberg, Horn

Hans Maassen, Cees

Blokker, Jaap Klemann, Jacques

Banens, Posaune

Jaap Schröder, Solo-Violine

Anner Bylsma, Violoncello

Gustav Leonhardt, Orgel

CONCERTO AMSTERDAM

Jaap SCHRÖDER, Konzertmeister

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Hervormde Kerk,

Bennebroek (Holland) - 1966/67

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Telefunken "Das Alte

Werk" | SAWT 9489-B | 1 LP -

durata 43' 12" | (p) 1968 | ANA

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Warner Classics |

LC 04281 | 2564-69599-2 | 2 CDs

- durata 146' 05" | (c) 2008 |

ADD | (BWV 59, 118)

Warner Classics

| LC 04281 | 2564-64763-2 |

1 CD - durata 66' 44" | (c)

2013 | ADD | (BWV 27, 158)

|

|

|

Cover

|

|

Deckengemälde in der

Wallfahrtskirche zu Veresheim von

Maria Knoller.

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

The cantata in

the broadest sense of the

word - whether as the church

cantata or the patrician,

academic or courtly work of

musical homage and festivity

- accompanied the Arnstadt

and Mühlhausen organist, the

Weimar chamber musician and

court organist, the Köthen

conductor and finally the

Leipzig cantor of St.

Thomas’-Bach-all through his

creative life, although with

fluctuating intensity, with

interruptions and

vacillations that still are

problems to musicological

research down to this very

day. The earliest preserved

cantata (“Denn du wirst

meine Seele nicht in der

Hölle lassen”) probably

dates, if it really is by

Bach, from the Arnstadt

period (1704) and is still

completely under the spell

of North and Central German

traditions. In the works of

his Mühlhausen years

(1707-08) - psalm cantatas,

festive music for the

changing of the council and

a funeral work (the “Actus

tragicus”) - we sense for

the first time something of

what raises Bach as a

cantata composer so much

higher than all his

contemporaries: the ability

to analyse even the most

feeble text with regard to

its form and content, to

grasp its theological

significance and to

interpret it out of its very

spiritual centre in musical

“speech” that is infinitely

subtle and infinitely

powerful in effect. In

Weimar (1708-17) new duties

pushed the cantata right

into the background to begin

with. It was not until the

Duke commissioned him to

write “new pieces monthly”

for the court services that

Bach once more turned to the

cantata during the years

1714-16, on texts written by

Erdmann Neumeister and

Salomo Franck. Barely thirty

cantatas can be ascribed to

these two years with a

reasonable degree of

certainty. It is most

remarkable that, on the

other and no courtly funeral

music has been preserved

from the entire Weimar

period, although there must

have been a considerable

demand for such works. It is

conceivable that many a lost

work, supplied with a new

text by Bach himself, lives

on among the Weimar church

cantatas.

In the years Bach spent at

Köthen (1717-23), on the

other hand, it is the

composition of works for

courtly occasions of homage

and festivity that come to

the fore, entirely in

keeping with Bach’s duties

as Court Conductor. It is

only during the last few

months he spent at Köthen

that we find him composing a

series of church cantatas

once again, and these were

already intended for

Leipzig. It was in Leipzig

that the majority of the

great church cantatas came

into being, all of them -

according to the most recent

research - during his first

few years of office at

Leipzig and comprising

between three and a maximum

of five complete series for

all the Sundays and feast

days of the ecclesiastical

year. But just as suddenly

as it began, this amazing

creative flow, in which this

magnificent series of

cantatas arose, appears to

have ended again. It is

possible that Bach’s regular

composition of cantatas

stopped as early as 1726;

from 1729 at the latest it

is evident that other tasks

largely absorbed his

creative energy,

particularly the direction

of the students’ Collegium

Musicum with its perpetual

demand for fashionable

instrumental music. More

than 50 cantatas for courtly

and civic occasions have

indeed been recorded from

later years, but considered

over a period of 24 years

and compared with the

productivity of his first

years in Leipzig they do not

amount to very much. We are

left with the picture of an

enigmatic silence in a

sphere which has ever

counted as the central

category in Bach’s creative

output.

But we only need cast a

superficial glance at the

more than 200 of the

master’s cantatas that have

come down to us in order to

see that this conception of

their position in Bach’s

total output is fully

justified. Bach has

investigated their texts

with regard to both their

meaning and their wording

with incomparable

penetration, piercing

intellect and unshakeable

faith, whether they are

passages from the Bible,

hymns, sacred poems by his

contemporaries or sacredly

trimmed poetry for courtly

occasions. He has

transformed and interpreted

these texts through his

music with incomparable

powers of invention and

formation, he has revealed

their essence and, at the

same time, translated the

imagery and emotional

content of each of their

ideas into musical images

and emotions. The perfect

blending of word and note,

the combination of idea

synthesis and depiction of

each detail of the text, the

joint effect of the baroque

magnificence of the musical

forms and the highly

differentiated attention to

detail, the skillful balance

between contrapuntal,

melodic and harmonic means

in the service of the word

and, not least, the

inexhaustible fertility and

greatness of a musical

imagination that is able to

create from the most feeble

‘occasional’ text a world of

musical characters - all

this is what raises the

cantata composer Bach so

much higher than his own and

every other age and their

historically determined

character, and imparts a

lasting quality to his

works. It is not their texts

alone and not their music

alone that makes them

immortal - it is the

combination of word and note

into a higher unit, into a

new significance that first

imparts to them the power of

survival and makes them what

they are above all else:

perfect works of art.

Wer Weiß, wie nahe mir

mein Ende! (BWV 27) is

linked, like the cantata

just discussed, to a Gospel

narration of an avvakening

from the dead (Luke 7:

11-17) - this time of the

young man in Nain, The idea

which the author of the text

has developed is basically

the same as before: Jesus

will awaken me and

therefore, he reasons, my

fear of death (dealt with in

the first and second

movements) is groundless; on

the contrary, death can only

be welcome to me. The

poetry, which recalls an

aria text by Erdmann

Neumeister in the third

movement (Neumeister:

"Wilkommen! will ich sagen,

so bald der Tod ans Bette

tritt..." remains free of

both didacticism and baroque

exaggerations, and is

distinguished instead by a

warmth of feeling that

places it among the most

successful texts ever set by

Bach. Bach's composition was

written for October 6, 1726,

and thus belongs to the

third of the yearly cycles

that have been preserved.

Although it begins with a

chorale, it is not a chorale

cantata: the inner movements

are not paraphrasos of a

hymn, nor do the opening and

closing chorales belong to

the same hymn. ln the

opening chorus the hymn tune

(”Wer nur den lieben Coll

läßt walten" - Who but lets

the dear God rule) is worked

into a meditative

instrumental texture with a

theme of its own (though

remotely related to the

chorale). Bach, however,

modifies this manner of

writing, wellknown from the

chorale cantatas, by the

inclusion of recitative

inserts in which the

motif-based orchestral

writing and the fixed meter

of the text are maintained.

This is the only example of

a recitative in three-four

time in the whole of Bach!

The first aria (movement 3)

is of unusual charm, and

requires as obbligato

instruments an oboe da

caccia and an obligato

harpsichord, which was

evidently replaced by an

obbligato organ at a later

performance. With its simple

song melody, Bach has found

just the right setting for

the character of its text,

and that of the entire

cantata. The second aria

movement in the cantata

(movement 5) is based on the

contrast of concepts ”Gute

Nacht - Weltgetümmel” (Good

night - wordly bustle),

which it also maintains

consistently in the music.

The initial Sarabande rhythm

is basically kept going

throughout the piece, but

already in the second half

of the ritornello and the

main section of the aria it

is filled out with lively

sixteenth-note figuration,

only the middle section and

the end of the last

ritornello being kept free

of this. Contrary to his

usual practice, Bach has

adopted a five-part setting

by Johann Rosenmüller as the

final chorale.

The occasion for which Bach

wrote his motet O Jesu

Christ, mein’s Lebens

Licht (BWV 118) is

unknown, but it may have

been for a Leipzig

University funeral service

during the mid-1730s. The

text is by Martin Böhme.

That the funeral ceremony

took place in the open air

is suggested by the

instrumentation, reminiscent

of older musical practices

and most unusual for Bach,

with two high horns,

cornetto, three trombones

and no continuo part. The

instrumental accompaniment

is so laid out that in spite

of a great degree of

independence it is able to

support the choir whenever

it enters. Simple harmonic

relationships and

uncomplicated part-writing

distinguish the movement,

whose effectiveness lies in

its instrumentation and

simplicity.

Der Friede sei mit dir

(BWV 158) is one of

Bach’s unusual cantatas, not

least because of its brevity

and sequence of movements.

Neither the author of the

text nor the circumstances

of its composition are

known, and the cover of the

score, which only exists as

a copy, names the Third Day

of Easter and the feast of

Candlemas (the Purification

of the Virgin) as the

liturgical occasions for

which the cantata was

intended. Cantata No. 158

probably consists of a

number of parts, and only a

fragment has survived. Our

knowledge of Bach cantatas

suggests that a seconcl aria

at least is missing before

the final chorale. The focal

point of the work is the

great bass aria with solo

violin ”Welt ade! ich bin

dei müde," to which the

soprano sings the chorale of

the same name line-for-line.

In its instrumental

symbolism and expressive

power the writing here is

related to the aria "Erbarme

dich” from the later St

Matthew Passion.

Wer mich liebet, der wird

mein Wort halten (BWV 59)

was intended for the First

Day of Whitsuntide and was

probably performed in 1724

in the Leipzig University

Church. This venue

presumably explains the

modest instrumentation of

the work, its extremely

unusual form and the

singular fact than in this

instance Bach composed only

the first four movements from

a text by Erdmann Neumeister

(from the latter’s fourth

annual cycle of cantatas for

1714). Perhaps Bach himself

felt the work to be

unsatisfactory, for a year

later it was expanded into

the large Cantata BWV 74 for

Whit Sunday. The first

movement is just as unusual

as the whole of the work.

The text, a quotation from

the Sunday Gospel, is

rendered four times in

canonic form, until

eventually the two soloists

come together in parallel

sixths; around this nucleus

strings and trumpets (two

instead of the usual three)

weave a fine

chamber-music-like setting

which continually reverts to

the two core motifs of the

vocal parts. The contrast

between the symbolic

strictness of the vocal

movement and the concertante

freedom of the instruments

seems in turn to have a

symbolic intention. The

recitative that follows

proceeds from A minor to the

G major of the succeeding

chorale; a harmonically rich

string accompaniment,

ecstatic exclamations and

the quick vocalises of the

concluding arioso

give this movement a hint of

rapturous exuberance that

establishes a link with the

chorale, of which this

exuberance is a natural

part. The bass aria with

obbligato violin combines a

concise ritornello

arrangement (ritornello -

first text section a a b -

ritornello, abbreviated -

second text section c d e -

ritornello) with a markedly

contrasting representation

of the two text sections.

Catchy, song-like melody is

used to juxtapose secular

and divine glory, while

expansive, emotional

melisrnas convey the bliss

of eternal life.

|

|

|

|