|

|

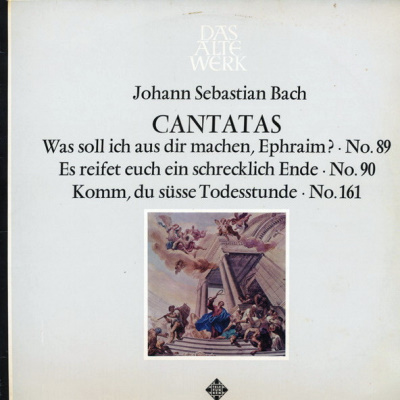

1 LP -

SAWT 9540-B - (p) 1969

|

|

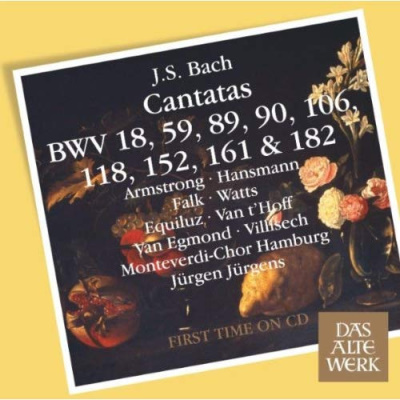

| 2 CDs -

2564-69599-2 - (c) 2008 |

|

KANTATEN

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

BACH (1685-1750) |

Kantate

"Was soll ich aus dir machen, Ephraim?",

BWV 89 - Kantate am 22. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

11' 43" |

|

|

für

Soli: Sopran, Alt, Baß; Chor; Oboe I/II;

Horn; Violine I/II; Viola; Continuo

(Violoncello und Orgel) |

|

|

|

|

- Aria (Baß): "Was soll ich aus dir

machen, Ephraim"

|

3' 38" |

|

A1 |

|

-

Recitativo (Alt): "Ja, freilich sollte

Gott ein Wort zum Urtheil sprechen"

|

0' 49" |

|

A2 |

|

-

Aria (Alt): "Ein unbarmherziges Gerichte

wird über dich gewiß ergehn!"

|

3' 07" |

|

A3 |

|

-

Recitativo (Sopran): "Wohlan! mein Herz

legt Zorn, Zank und Zwietracht hin" |

1' 02" |

|

A4 |

|

-

Aria (Sopran): "Gerechter Gott, ach,

rechnest du?" |

2' 33" |

|

A5 |

|

-

Choral (Chor): "Mir mangelt zwar sehr

viel" |

0' 56" |

|

A6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kantate

"Es reifet euch ein schrecklich Ende",

BWV 90 - Kantate am 25. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis

|

|

12' 00" |

|

|

für

Soli: Alt, Tenor, Baß; Chor; Trompete;

Violine I/II; Viola; Continuo

(Violoncello und Orgel) |

|

|

|

|

-

Aria (Tenor): "Es reifet [reißet] euch ein

schrecklich Ende"

|

6' 39" |

|

A7 |

|

-

Recitativo (Alt): "Des Hòchsten Gète wird

von Tag yu Tag neu" |

1' 34" |

|

A8 |

|

-

Aria (Baß): "So löschet im Eifer der

rächende Richter" |

3' 44" |

|

A9 |

|

-

Recitativo (Tenor): "Doch Gottes Auge

sieht auf uns als Auserwählte" |

0' 39" |

|

A10 |

|

-

Choral (Chor): "Leit' uns mit deiner

rechten Hand" |

1' 12" |

|

A11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kantate

"Komm, du süße Todesstunde", BWV 161

- Kantate am 16. Sonntag nach Trinitatis,

desgleichen am Feste Mariä Reinigung

|

|

17' 00" |

|

|

für

Soli: Alt, Tenor; Chor; Flauto I/II

(Querflöten); Violine I/II; Viola; Orgel

und Continuo |

|

|

|

|

-

Aria (Alt): "Komm, du süße Todesstunde" |

5' 19" |

|

B1 |

|

-

Recitativo (Tenor): "Welt, deine Lust ist

Last" |

2' 14" |

|

B2 |

|

-

Aria (Tenor): "Mein Verlangen ist, den

Heiland zu umfangen" |

6' 16" |

|

B3 |

|

-

Recitativo (Alt): "Der Schluß ist schon

gemacht" |

2' 26" |

|

B4 |

|

-

Coro: "Wenn es meines Gottes Wille" |

3' 59" |

|

B5 |

|

-

Choral (Chor): "Der Leib zwar in der Erden

von Würmern wird verzehrt" |

1' 33" |

|

B6 |

|

|

|

|

|

Sheila Armstrong, Sopran

Helen

Watts, Alt

Kurt Equiluz, Tenor

Max van Egmond, Baß

JUNGE KANTOREI / Joachim

Martini, Leitung (BWV 89)

MONTEVERDI-CHOR,

HAMBURG / Jürgen Jürgens,

Leitung (BWV 90 und 161)

Ad Mater, Lilian Lagaay, Oboe

Frans Vester, Joost Tromp,

Querflöte

Wim Groot, Trompete

Hermann Baumann, Horn

Anner Bylsma, Violoncello

Gustav Leonhardt, Orgel

CONCERTO AMSTERDAM

Jaap SCHRÖDER, Konzertmeister

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Hervormde Kerk,

Bennebroek (Holland):

- 5/8 Settembre 1965 (BWV 90, 161)

- 31 Marzo / 1, 7/8 Aprile 1969

(BWV 89)

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Telefunken "Das Alte

Werk" | SAWT 9540-B | 1 LP -

durata 40' 43" | (p) 1969 | ANA

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Warner Classics |

LC 04281 | 2564-69599-2 | 2 CDs

- durata 146' 05" | (c) 2008 |

ADD

|

|

|

Cover

|

|

Klosterkirche

Veresheim. Kuppelfresko über der

Orgelempore von Martin Knoller

(1725-1804), "Jesus treibt die

Händler aus dem Tempel"

(Ausschnitt)

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

The cantata in

the broadest sense of the

word - whether as the church

cantata or the patrician,

academic or courtly work of

musical homage and festivity

- accompanied the Arnstadt

and Mühlhausen organist, the

Weimar chamber musician and

court organist, the Köthen

conductor and finally the

Leipzig cantor of St.

Thomas’-Bach-all through his

creative life, although with

fluctuating intensity, with

interruptions and

vacillations that still are

problems to musicological

research down to this very

day. The earliest preserved

cantata (“Denn du wirst

meine Seele nicht in der

Hölle lassen”) probably

dates, if it really is by

Bach, from the Arnstadt

period (1704) and is still

completely under the spell

of North and Central German

traditions. In the works of

his Mühlhausen years

(1707-08) - psalm cantatas,

festive music for the

changing of the council and

a funeral work (the “Actus

tragicus”) - we sense for

the first time something of

what raises Bach as a

cantata composer so much

higher than all his

contemporaries: the ability

to analyse even the most

feeble text with regard to

its form and content, to

grasp its theological

significance and to

interpret it out of its very

spiritual centre in musical

“speech” that is infinitely

subtle and infinitely

powerful in effect. In

Weimar (1708-17) new duties

pushed the cantata right

into the background to begin

with. It was not until the

Duke commissioned him to

write “new pieces monthly”

for the court services that

Bach once more turned to the

cantata during the years

1714-16, on texts written by

Erdmann Neumeister and

Salomo Franck. Barely thirty

cantatas can be ascribed to

these two years with a

reasonable degree of

certainty. It is most

remarkable that, on the

other and no courtly funeral

music has been preserved

from the entire Weimar

period, although there must

have been a considerable

demand for such works. It is

conceivable that many a lost

work, supplied with a new

text by Bach himself, lives

on among the Weimar church

cantatas.

In the years Bach spent at

Köthen (1717-23), on the

other hand, it is the

composition of works for

courtly occasions of homage

and festivity that come to

the fore, entirely in

keeping with Bach’s duties

as Court Conductor. It is

only during the last few

months he spent at Köthen

that we find him composing a

series of church cantatas

once again, and these were

already intended for

Leipzig. It was in Leipzig

that the majority of the

great church cantatas came

into being, all of them -

according to the most recent

research - during his first

few years of office at

Leipzig and comprising

between three and a maximum

of five complete series for

all the Sundays and feast

days of the ecclesiastical

year. But just as suddenly

as it began, this amazing

creative flow, in which this

magnificent series of

cantatas arose, appears to

have ended again. It is

possible that Bach’s regular

composition of cantatas

stopped as early as 1726;

from 1729 at the latest it

is evident that other tasks

largely absorbed his

creative energy,

particularly the direction

of the students’ Collegium

Musicum with its perpetual

demand for fashionable

instrumental music. More

than 50 cantatas for courtly

and civic occasions have

indeed been recorded from

later years, but considered

over a period of 24 years

and compared with the

productivity of his first

years in Leipzig they do not

amount to very much. We are

left with the picture of an

enigmatic silence in a

sphere which has ever

counted as the central

category in Bach’s creative

output.

But we only need cast a

superficial glance at the

more than 200 of the

master’s cantatas that have

come down to us in order to

see that this conception of

their position in Bach’s

total output is fully

justified. Bach has

investigated their texts

with regard to both their

meaning and their wording

with incomparable

penetration, piercing

intellect and unshakeable

faith, whether they are

passages from the Bible,

hymns, sacred poems by his

contemporaries or sacredly

trimmed poetry for courtly

occasions. He has

transformed and interpreted

these texts through his

music with incomparable

powers of invention and

formation, he has revealed

their essence and, at the

same time, translated the

imagery and emotional

content of each of their

ideas into musical images

and emotions. The perfect

blending of word and note,

the combination of idea

synthesis and depiction of

each detail of the text, the

joint effect of the baroque

magnificence of the musical

forms and the highly

differentiated attention to

detail, the skillful balance

between contrapuntal,

melodic and harmonic means

in the service of the word

and, not least, the

inexhaustible fertility and

greatness of a musical

imagination that is able to

create from the most feeble

‘occasional’ text a world of

musical characters - all

this is what raises the

cantata composer Bach so

much higher than his own and

every other age and their

historically determined

character, and imparts a

lasting quality to his

works. It is not their texts

alone and not their music

alone that makes them

immortal - it is the

combination of word and note

into a higher unit, into a

new significance that first

imparts to them the power of

survival and makes them what

they are above all else:

perfect works of art.

Was soll ich aus dir

machen, Ephraim? (BWV 89)

has its origins in the first

Leipzig annual cantata cycle

and was composed for 24

October 1725 (twenty-second

Sunday after Trinity). The

anonymous text begins with a

quotation from the Old

Testament which hints at the

Sunday Gospel reading and is

then construed in a double

sequence of recitative and

aria. The impact of the Old

Testament language inspired

Bach to compose a grandiose

and gloomy opening movement.

This is a bass arioso of the

highest rhetorical power

around which oboes, strings

and continuo (the horn has

only a supporting function),

three contrary motifs -

sighs, pathos-laden broken

chords and murmuring

semiquavers - develop in

ever new constellations. The

two arias stand out from

this movement on account of

markedly simple

instrumentation, but at the

same time are designed as a

contrasting pair. The alto

aria (with continuo only)

conjures up in D minor the

terrors of the Old Testament

court (not by coincidence

with the aid of that already

slightly archaic theme type

given to the Old Covenant in

BWV 106). The soprano aria,

in B flat major with

obbligato oboe, prepared by

way of the arioso concluding

phrase of the second

recitative, sings of the

hope in Christ's redeeming

sacrifice with almost

dancelike grace and a

relaxed mood. The final

chorus is a simple,

songelike setting, although

not entirely without

hannonic surprises to point

up the text.

Es reifet euch ein

schrecklich Ende (BWV 90)

was composed for the

tvventy-fifth Sunday after

Trinity, i.e. 14 November

1723, and thus also belongs

to the first Leipzig annual

cantata cycle. The anonymous

text concentrates on the

visions of horror of the

final period before the last

judgement; the hope of the

“chosen people” is not

uttered until the second

recitative and the chorale.

The deadly earnestness of

this text is matched by the

almost gloomy composition,

which with uncustomary

persistence circles around D

minor (the tonic) and G

minor, and which in the two

chief arias that dominate

the work depict the text's

emotions in a highly graphic

fashion: the terrible end

and the sinfulness of man in

vehement coloraturas,

chromatic runs, broken-off

phrases and hurled-out

declamatory motifs in the

tenor’s highest range; the

vision of the zealous judge

of the world in grandiose

war music, completely built

up on signal motifs, with

concertante trumpet, the

symbolic instrument of

warfare. The two secco

recitatives are brief and

unadorned, but worked out

down to the last text detail

both as regards declamation

and harmonically. In

particular the first, which

contrasts God's goodness and

the worlds ingratitude,

displays an abundance and

power of musical depiction

of the text which were not

customary even for Bach. The

closing chorus is a

song-like setting which

begins in simple fashion and

then increases in harmonic

splendour, culminating in

one of Bachs most astounding

harmonic applications (D flat

major inserted at the word

“Stündelein") and eventually

fading out on the sustained

D major of “ewig bei dir

sein" (join thee in

eternity).

Komm, du süße Todesstunde

(BWV 161) is based on

the raising of the widow of

Nain‘s son. There is poetic

scholarship in the Old

Testament image of the lion

slain by Samson, in whose

corpse honey bees have made

their nest. As in BWV 106,

the recorders, often scored

in parallel, play the “quiet

notes,” and the opening alto

aria contains the melody “O

Haupt voll Blut und Wunden”

as a solo in the organ part.

The trio setting for flutes

and continuo expands with

the addition of the alto

voice and the chorus into

elaborate five-part writing.

The melody of the more

agitated tenor aria “Mein

Verlangen” is, like that of

the alto aria, developed

from the song melody,

without this being obvious;

it presents the longing for

death as a longing for

resurrection. Particular

care is taken over text

interpretation in the accompagnato

recitative: “Schlaf" (sleep)

is evoked by descending

lines, “auferwecken” (awake)

is portrayed with lively

movement, “letzter

Stundenschlag” (the final

hour) with the tolling of

the bell for the dead (first

flute) and the peal of bells

on the second flute and

pizzicato strings - the

unavoidable open strings of

the lower stringed

instruments are intentional.

The chorus “Wenn es meines

Gottes Wille" intensifies the

joyful anticipation of death

to such a degree that the

final chorale is altered in

its otherwise subdued

expression by the lively

counterpoint of the

recorders (in unison).

|

|

|

|