|

|

3 LPs

- SKH 21/1-3 - (p) 1969

|

|

| 2 CDs -

0825646964581 - (c) 2015 |

|

FAVOLA IN

MUSICA

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Claudio MONTEVERDI (1567-1643) |

L'Orfeo

|

|

|

|

|

Toccata |

|

1' 48" |

A1

|

|

Prologo

|

|

5' 23" |

A2

|

|

1. Akt |

|

16' 57" |

A3 |

|

2. Akt

|

|

24' 39" |

B

|

|

3. Akt |

|

25' 12" |

C |

|

4. Akt

|

|

18' 26" |

D |

|

5. Akt |

|

15' 07" |

E |

|

"Akustische

Werkeinführung in die erste ungekürzte

Gesamtaufnahme in authentischer

Besetzung mit Originalinstrumenten" |

|

--' --" |

F |

|

Text:

Nikolaus Harnoncourt |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rotraud

Hansmann, La Musica

Lajos

Kozma, Orfeo

Rotraud

Hansmann, Euridice

Cathy

Berberian, Messaggiera

Cathy

Berberian, Speranza

Nikolaus

Simkowsky, Caronte

Eiko

Katanosaka, Proserpina

Jacques Villisech, Plutone

Max van Egmond, Apollo

Eiko Katanosaka, Ninfa

Günther Theuring, Pastor 1

Nigel Rogers, Pastor 2

Kurt Equiluz, Pastor 3

Max van Egmond, Pastor 4

Nigel Rogers, Spirito 1

Kurt Equiluz, Spirito 2

Max van Egmond, Spirito 3

Pastori

und Spiriti (Chöre)

CAPELLA ANTIQUA, München

- Konrad Ruhland, Leitung

|

CONCENTUS MUSICUS

WIEN mit

Originalinstrumenten

-

Herbert Tachezi, Gustav

Leonhardt, Johann Sonnleitner, Orgel, Cembalo,

Virginal, Regal

-

Alice Harnoncourt, Walter

Pfeiffer, Peter Schoberwalter,

Stefan Plott, Violine

-

Alice Harnoncourt, Walter

Pfeiffer, Violini Piccoli

-

Josef de Sordi, Viola

- Kurt Theiner, Tenorviola

- Hermann

Höbarth, Violoncello

-

Eduard Hruza, Violone

-

Erna Gruber, Barockharfe

-

Eugen M. Dombois,

Michael Schaeffer,

Chitarroni,

Lauten

- Alice

Harnoncourt, Kurt

Theiner, Pardessus

de Viole

- Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Elli

Kubizek, Hermann

Höbarth, Tenor-

und Baß-Viola da

gamba

- Hans Pöttler,

Ernst Hoffmann,

Helmut Berger,

Andreas Wenth,

Otto Fleischmann,

Dulzian

- Don Sithers,

Ulrich Brandhoff,

Cornetti

(Zinken)

- Jürg

Schaeftlein,

Leopold Stastny,

Helga Tutschek,

Bernhard Klebel, Renaissanceblockflöten

- Josef Spindler,

Richard Rudolf,

Hermann Schober,

Günter Spindler, Naturtrompeten

Nikolaus

HARNONCOURT,

Gesamtleitung

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Casino Zögernitz,

Vienna (Austria) - Dicembre 1968

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Telefunken "Das Alte

Werk" | SKH 921/1-3 | 3 LPs -

durata 48' 58" - 43' 38" - 15' 07"

| (p) 1969 | ANA

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Warner Classics

"Das Alte Werk" | LC 06019 |

0825646964581 | 2 CDs - durata

48' 59" - 58' 50" | (c) 2015 |

ADD |

|

|

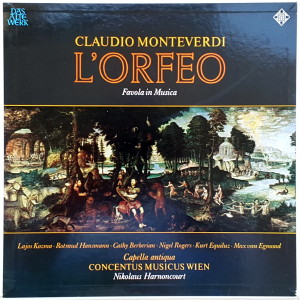

Cover

|

|

"Orfeo und Euridice",

Gemälde von Rolland Savery

(1576-1639).

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Claudio

Monteverdis L'ORFEO

Mankind

must have recognized very

early the many and varied

artistic possibilities in

the combination of poetry

and music. Every poetic

statement, however clearly

formulated it may be, is

capable of interpretation

through a variety of nuances

and stresses, so that

several entirely different

interpretations are often

possible.

Music knows no concrete

statement, and yet already

in its earliest beginnings

it was able to arouse the

emotions of human beings-to

move, to delight, to excite.

These effects of music were

always felt to be magical,

which is why music has

played an essential part in

the ritual of all religions.

It will thus be readily

understandable that poets

have, since earliest times,

made use of these

possibilities and performed

their poems in song. In some

cultural regions singer und

poet mean one and the same

thing. The Greek epics, and

possibly even the dramas,

must be imagined presented

in song.

In the Christian-Western

culture of the middle ages

and earlier modern times,

poetry and art-music were

not so intimately connected.

ln the ballades, virelais

and motets of the 13th, 14th

and 15th centuries written

in several voices and

extremely complex settings,

the music is very much in

the foreground; the text

frequently can hardly be

understood. Later, in the

high renaissance, enthusiasm

for ancient Greek poetry was

so strong that it was even

attempted to reintroduce the

ancient manner of recitation

- even though there was only

the vaguest conception of

this. There thus arose

around 1600 a completely new

musical style - the

recitative, monody the vocal

concerto. The sole object

here was to reproduce the

text as understandably as

possible and with the

maximum expression. The

music had to remain

completely in the

background; its task was to

provide an unobtrusive

harmonic basis. In passages

of particularly intense

expression the content of

the words was highlighted as

clearly as possible through

suitable musical and

harmonic interpretation,

frequently of powerful

effect.

The rhythm of this

recitation song had to

follow the speech rhythms,

which were thus rendered

more forceful. The poetry

made its point more

intensively than in mere

declamation.

Monteverdi's Orfeo

came into being only a few

years after the first

experiments had been made in

this new recitative dramatic

style. The author of the

text, A. Striggio, a court

official of the Duke of

Mantua, was a friend of the

composer’s, so this work is

sure to have been born of a

close collaboration. It is

the first opera in which, on

the one hand, poetry had

primacy of place in

accordance with the new

ideals, but on the other

music too was fully employed

with all its abundance of

forms. In this first of

Monteverdi’s operas all

those forms and

possibilities are

anticipated or intimated

that appear in the operas of

the following centuries: the

characterizing overture, the

aria (even with “da capo’),

the strophic song, various

‘leitmotivs’, dramatically

motivated instrumentation

and, as a matter of course,

the recitative. All these

forms were not newly created

by Monteverdi; he blended

the entire stock of newest

and older possibilities into

a unity that was indeed new.

Thus the opera with which

the baroque period in music

is so splendidly opened is,

at the same time, the last

large-scale work in which

the wealth of forms and the

rich and colourful sound

palette of renaissance music

are laid out: the orchestra

demanded for Orfeo

corresponds down to the

smallest detail to that of

the ‘intermedia’ that were

played decades earlier as

entractcs in theatrical

performances. The shepherds’

scenes of the first and

second acts are full of the

traditional pastoral

madrigal.

The new monody (the

recitative) was intensified

by Monteverdi to the highest

power of expression, many a

taboo of the rules of

harmony being ruthlessly

broken - "for the sake of

truth" as he emphasized in

the course of a dispute.

The choice of Orpheus as a

subject for his first

dramatic work is typical: as

"Greek drama" suited to the

new style based on

antiquity, and at the same

time programmatic, singing

the praises of music which

conquers all.

Although Monteverdi states

the orchestra required on

the first page of his

printed full score, he

nevertheless leaves the

exact use of these media to

the interpreter in each

case, as was a matter of

course at that time. This

freedom - in any case

reduced here - has two

reasons. First, the

constitution of the

orchestra was different in

every place, and the local

conductor had to be able to

adapt each work to his own

particular possibilities:

reducing the orchestration

when his resources were not

sufficient, but also using

all the available forces

when this enhanced the work.

Second: nearly all the

instrumentalists of that

time were also composers; it

was a matter of course for

them to collaborate

creatively in every

interpretation, and not

merely reproduce a given

musical text.

The orchestra in “L’Orfeo"

is divided into “foundation”

and “ornament” instruments.

The foundation

instruments, which are

responsible for the playing

and harmonization of the

bass part, are the

chitarrone, lute, harp,

harpsichord, virginals,

organ und regal. The ornament

instruments are all

the wind instruments, the

string instruments and the

lutes as far as they do not

play the bass. Monteverdi

allots the two worlds of

this opera, the world of the

shepherds in Thrace and the

realm of shadows of the

Underworld, to two

fundamentally different

groups of instruments:

flutes, strings and plucked

instruments for the pastoral

sphere, and cornetts,

trombones and regal for the

Underworld. The distribution

of the "foundation

instruments" as

accompaniments for the

various characters is, with

few exceptions, left to the

performer. In this

performance the most

important figures have been

accompanied as far as

possible by the same

instruments, so that a kind

of characterization in sound

makes the dialogue more

easily understood. Orpheus

is accompanied by the noble

sounds of the harp and the

organ, the shepherds by the

harpsichord, lute or

chitarrone, the gods of the

Underworld by the regal,

sometimes on its own,

sometimes with trombones.

According to the rules of

that time, these instruments

should never push their way

into the foreground through

over-rich passage work or

skillful improvisations.

Their task is always to

serve the song, the

declamation, and they should

only underline the accent of

the words through their tone

colours, harmonies and

combinations of notes. In

order to be able to react

spontaneously to the

singers’ nuances, these

parts must be improvised.

One of the most

widely-discussed problems in

the performance of older

music is the whole complex

of improvisation and

embellishment. In our view,

present-day performances

that aim at the greatest

possible authenticity often

go too far in this respect.

Continuo players demonstrate

industrious contrapuntal

feats which are indeed at

times brought off with great

skill, but which are only

rarely stylistically suited.

The continuo, after all,

must never divert the

attention from the main

musical elements; this

applies in a special degree

to the early period of the

baroque.

For improvisatory

embellishments bv the

singers there are indeed

many instructional works,

but there are also

contemporary voices,

particularly regarding the

works of Monteverdi, warning

that nothing, or as little

as possible, should be added

to the musical text. Indeed,

Monteverdi has written out

more embellishments himself

than any other composer of

his time, and it is quite

obvious that where he did

not write any embellishments

he did not want any sung. In

this performance only some

cadences have been

embellished, mainly in the

“lighter” roles, least of

all for Orfeo himself. In

our opinion embellishment

should be applied even more

sparingly in a gramophone

recording than in a concert,

since every improvisation is

fundamentally something

unique which, when heard

again - especially when

heard again repeatedly -

becomes ridiculous.

Monteverdi was a practical

musician. He had joined the

orchestra of the Duke of

Mantua as a violinist at the

age of twenty-three. Here he

found an abundance of

stimuli, for some of his

colleagues were famous

composers (Giacches de Wert,

Giovanni Gastoldi, Benedetto

Palavicino). In the course

of his travels - 1595 to

Hungary, 1599 to Flanders -

he had the opportunity of

hearing other leading

European orchestras and

making the acquaintance of

other composers. These

musical stimuli bore fruit

in the madrigals he wrote

during these years, and also

very clearly in the pastoral

scenes of his Orfeo, In 1601

Monteverdi became "Maestro

della Musica", that is,

Director of the Court Music.

He wrote his "favola in

rnusica l’Orfeo for a

performance in the Academia

degl’ Invaghiti" on the 22nd

February 1607. It was later

repeated in the Court

Theatre, and also performed

in other cities such as

Cremona and Turin. The two

printed editions of 1609 and

1615, dedicated to the

Gonzaga Prince Francesco,

prove the work’s

extraordinary success.

The places where it was

performed were, by today’s

standards, quite tiny, and

the audience hardly numbered

more than the performers.

From the printed list of the

orchestral forces, it would

seem that only the string

instruments were doubled in

the tutti (thus two players

to each part), all the other

ornament instruments were

singly represented. The

choruses too are conceived

for the smallest forces (the

madrigal ensembles of that

time were hardly more than

one voice to each part),

also on account of the

balance with the instruments

and within the worlt as a

whole.

Of the instruments used

here, some are original,

others copies made after

painstaking study. Practical

music-making of diverse

character has shown that the

entire instrumental group,

despite all its variety and

colourfulness, adds up to a

unity, and that it is

impossible to incorporate

instruments of other epochs

or other tone conceptions.

For example, any modern

harp, however sensitively it

may be played, falls

completely out of the

picture among these

renaissance sounds - its

reverberation is too long,

its tone too dark and

cloudy. The baroque harp

has, however, on account of

its small resonating body

and since it is not

encumbered by any mechanical

action, a light, airy tone

that stands out clearly from

the other plucked

instruments, the lutes and

the harpsichords, yet not

too obtrusively. The group

of continuo instruments with

plucked strings thus ranges

from the big Italian

harpsichord with its

brilliant tone through the

clearly defined virginals (a

little cross-strung

harpsichord with only one 8’

register), the chitarrone,

equipped with metal strings

in accordance with

Praetorius’s data (the

favourite instrument for the

accompaniment of singers in

the new monodic style) and

the soft and

sensitive-sounding lute to

the harp.

In addition, Monteverdi

demands an “organs di

legno”, a gently sounding

organ with pipes only of

wood. Its tone often

provides the background for

the harp, the lute or the

chitarrone; it welds the

entire sound together in the

tutti without obtruding. The

regal, with its snarling

tone, demanded for the

Underworld acts, also places

these in the strongest

contrast to the pastoral

scenes as regards tone

colour.

The string ensemble is

richer than at any time

before or since: violini

piccoli (tuned a fourth

higher than normal violins

and sounding an octave

higher than written),

ordinary violins, violas,

’cellos (Monteverdi calls

the ’cello "Viola da brazzo”

to underline its membership

of the violin family, in

contrast to the gambas),

gambas and violone. The

recorders (renaissance

instruments made of one

piece) belong to the world

of the shepherds; cornets,

dulcian and trombones,

together with the regal,

make up the orchestra of the

Underworld scenes.

The four trumpets, which are

used only in the brief

Toccata before the beginning

of the Prologue, for an

exception. This Toccata has

no connection with the rest

of the work; it has a

similar function to a

national anthem played today

at the beginning of a

festive concert - it is a

kind of Gonzaga fanfare.

Monteverdi writes on it as

follows: "This Toccata

should be played three times

before the curtain rises, by

all the instruments. If it

is desired that the trumpets

play with mutes, it must be

played one tone highet". The

reason for this instruction

is that the trumpet mutes of

that time made the

instrument sound one tone

higher. It is very probable

that Monteverdi gave

preference to the D major

version (with mutes) over

the C major version, on

account of the key

relationship with the first

ritornello, which begins in

D minor. Muted natural

trumpets sound much softer

than open ones; the four

court trumpeters, who did

not belong to the orchestra

but were officers, probably

stood in front of the

curtain, while the orchestra

sat behind it. For the sake

of tonal balance, and

probably also so as not to

disconcert the audience

sitting quite near in the

small room, the trumpets

were to be muted. All three

repetitions must naturally

be played either with or

without mutes; a contrast

effect perhaps in one of the

repetitions would be

stylistically false, and

impossible of execution on

natural trumpets on account

of the transposing effect of

the mutes. With the muted

natural trumpets used in

this recording, correction

of the flat-sounding notes

(f and a) by means of the

embouchure was only possible

to a limited degree.

In the setting up of the

orchestra, musical and

dramatic grounds alike were

taken into consideration.

Strings and wind were

treated as separate choirs,

not divided according to

parts in the usual fashion.

We thus hear the string

orchestra from the left,

while the cornets, trombones

and the regal are placed on

the right. In this manner a

localization of certain

scenes is attempted: the

world of the shepherds on

the left, the Underworld on

the right. The continuo

instruments are distributed

across the entire width, in

order to achieve a suitable

background in the tutti. The

stereophonic distribution is

therefore not conceived for

the individual sections, but

for the work as a whole. It

can thus easily happen that

a lengthy scene comes only

from one side when the

singer and the instruments

accompanying him are on this

side. The positioning of the

orchestra remains unchanged

throughout the work; the

positions and movements of

the singers follow a

detailed plan. In the first

act, for instance, Orpheus

comes to meet the shepherds

from the right - the

messenger of ill tidings in

the second act comes from

the left - in the third act

Charon and the spirits of

the Underworld are on the

right, from where the sounds

of the trombones and regal

also come; Orpheus and

Speranza (Hope) come from

the left. Orpheus later

crosses the Styx in the

boat, and is then also on

the right. This sketch of

the seating of the orchestra

is intended to facilitate

the recognition of the

instruments when listening.

The allegorical Prologue

from Musica is introduced by

a Ritornello heard four

times in the course of the

opera. It represents the

gay, bright world of music,

devoid of any tragedy or

mystery. (At the end of the

second act it is like a

recollection of lost

happiness, a farewell to the

world of the shepherds. At

the beginning of the fifth

act this piece has the

effect of the mint cruel

irony. Orpheus has been

hurled back to the light, he

must live on whether he

wants to or not, outwardly

the world of the shepherds

has remained as it was.)

Musica greets the audience

in the Prologue and

sings of the power of music.

Between the verses of her

song a part of the opening

Ritornello is repeatedly

played, each time in a

different instrumentation to

symbolize the variety of

music: strings, recorders,

plucked instruments,

trombones. The first act

begins with a 'da capo’ aria

for Pastor II, its form

underlined by the change of

continuo instrument:

harpsichord, chitarrone,

harpsichord.

The pastoral idyll of the First

Act has a particularly

clear musical form: the pair

of choruses that is repeated

in reversed order "Vieni

Imeneo" and "Lasciate i

monti" frames the central

song of praise of Orpheus

and Eurydice; the songs of

joy and thanksgiving of the

shepherds before the closing

chorus "Ecco Orfeo" are

bound together into an

entity by the three-fold

repetition of a string

ritornello.

The Secound Act

begins with a joyful ballet

scene between Orpheus and

the shepherds. Dance songs

and dance-like solo

ritornelli here follow one

another without a break.

Monteverdi has obviously

made use here of the stimuli

he had gathered on his

journeys, especially as

regards French dance music.

Unexpectedly, Silvia

(Messagiera), Eurydice's

friend, interrupts the

idyll. As the bringer of ill

tidings she tells of

Eurydice’s sudden death.

Here and in the dialogue

that follows, as well as in

Orpheus's lament, Monteverdi

uses all possibilities of

interpretation of the test

through the harshest

treatment of dissonances and

the unexpected juxtaposition

of unrelated keys.

The change of scene to the Third

Act is illustrated by

the completely new sounds of

the cornets, the trombones

and the regal. Monteverdi

writes: “here the trombones,

cornets and the regal beginn

to play and the violins, the

organ and the harpsichord

are silent, the scene

changes".

The main part of the Third

Act consists of

Orpheus’s attempt to

overcome the insensitive

watchman Charon through the

power of his music. This

scene is framed by a gentle

Sinfonia played at the

beginning and at the end in

different instrumentation.

(The same piece is heard

again in the last act before

the appearance of Apollo. It

symbolizes the super-natural

power of music, with which

Orpheus bewitches the gods

of the Underworld just as

much as the lord of

Parnassus.) The chorus with

which the third act closes

is framed by the same

Sinfonia as introduces the

act, so that this act again

displays a self-contained

musical form.

The Fourth Act

continues from the third

without a break. Orpheus has

entered the Underworld.

Proserpina, deeply moved by

his singing, implores her

husband Pluto to set

Eurydice free. In the middle

of the completely impersonal

coldness of the world of

shadows, her singing is now

full of the deepest feeling

and human warmth. The spell

is broken, this act is

dominated by a "sympathetic"

music, the Underworld has

thawed as it were. All the

harder and more dramatically

effective is the renewed

freezing into relentlessness

after Orpheus’s failure

through doubt.

Both acts in the Underworld

close with the big,

impersonally commenting

chorus of the spirits of the

shadows "E la virtute"; this

again is framed by the cold

sounds of a sinfonia with

cornets, trombones and

regal. The Underworld again

shows itself to be of stone,

unconquerable, devoid of

human feeling.

At the beginning of the Fifth

Act we are led back

again to the world of the

shepherds by the familiar

Ritornello. The monologue of

Orpheus, who wanders around

lamenting, accompanied only

by the chitarrone and the

organ, is one of the most

broadly spannend and

greatest recitatives in the

whole of operatic

literature.

Thie actual ending of the

Orpheus saga, in which the

despairing singer turns away

from women altogether and is

finally torn to pieces by

the raging Maenads, was

altered in nearly all

retellings of the story in

the renaissance and baroque

eras. It is probable that a

first version of

Monteverdi’s Orfeo, which is

even reputed to have been

performed at Cremona, had a

tragic ending. Such an

"unbaroque" conclusion could

not satisfy at that time. So

Striggio and Monteverdi

finally found a “compromise”

solution. Orpheus may not,

as in other versions, live

on with Eurydice - an all

too smooth ending to the

fable; he is, however, not

killed but led up to

Parnassus by Apollo. The

dance chorus of the

shepherds sung to end the

opera turns into a wild

Moresca, which may well be a

recollection of the wild

dance of the cruel

Bacchantae. In this dance

the entire orchestra -

pastoral world and

Underworld - are united in a

symbolic conclusion.

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt

|

|

|

|