|

|

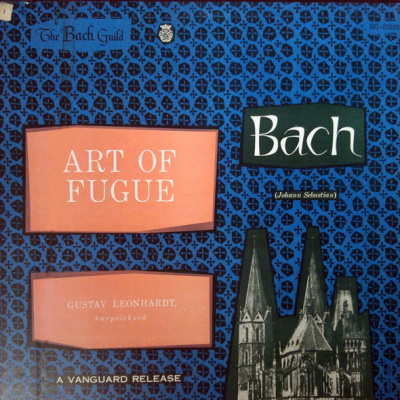

2 LPs

- BG-532/3 - (p) 1954

|

|

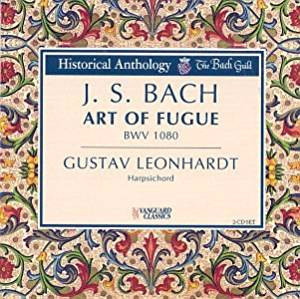

| 2 CDs -

OVC 2011/12 - (p) & (c) 1993 |

|

| 2 CDs -

ATM-CD-1652 - (p) & (c) 2006 |

|

ART OF FUGUE

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

BACH (1685-1750) |

ART OF FUGUE, BWV 1080

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.

Simple Fugue |

Gr.

I |

D.

I |

|

5' 11" |

A1

|

|

2.

Simple Fugue - theme inverted |

Gr.

III |

D.

II |

|

3' 30" |

A2

|

|

3.

Simple Fugue |

Gr.

II |

D.

III |

|

3' 37" |

A3 |

|

4. Simple

Fugue - theme inverted

|

Gr.

IV |

D.

IV |

|

7' 26" |

A4

|

|

5.

Fugue in contrary motion |

Gr.

V |

D.

IX |

|

4' 07"

|

B1

|

|

6.

Double Fugue in 12th

|

Gr.

IX |

D.

VI |

|

2' 48" |

B2

|

|

7.

Double Fugue in 10th |

Gr.

X |

D.

VII |

|

5' 15" |

B3 |

|

8.

Fugue in contrary motion, with diminution |

Gr.

VI |

D.

X |

|

4' 06" |

B4

|

|

9.

Canon in the 10th

|

Gr.

XIV |

D.

VIII |

|

6' 38" |

C1 |

|

10.

Fugue in contrary motion, with bouble

augmentation |

Gr.

VII |

D.

XI |

|

5' 08" |

C2 |

|

11.

Canon in the 12th

|

Gr.

XIII |

D.

V |

|

1' 58" |

C3 |

|

12.

Canon in the octave |

Gr.

XII |

D.

XII |

|

2' 31" |

C4 |

|

13.

Triple Fugue - three voice

|

Gr.

VIII |

D.

XIII |

|

5' 46" |

C5 |

|

14.

Triple fugue - four voice |

Gr.

XI |

D.

XIV |

|

6' 47" |

D1 |

|

15.

Canon in contrary motion, by augmentation |

Gr.

XV |

D.

XV |

|

3' 18" |

D2 |

|

16.

Mirror Fugue |

Gr.

XVIII a. |

D.

XVI |

|

3' 04" |

D3

|

|

17.

Mirror Fugue - inverse of 16

|

Gr.

XVIII b. |

D.

XVII |

|

3' 12" |

D4 |

|

18.

Mirror Fugue

|

Gr.

XVI a. |

D.

XVIII |

|

2' 39" |

D5 |

|

19.

Mirror Fugue - inverse of 18 |

Gr.

XVI b. |

D.

XIX |

|

2' 42" |

D6 |

|

20.

Unfinished Fugue, on BACH |

Gr.

XIX |

D.

XX |

|

6' 46" |

D7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note:

To the right of each contrapunctus

will be found the corresponding

numbers in the score edited by

Wolfgang Graeser, Breitkopf and

Hartel, Leipzig 1927 (Gr.) and

that by Hans T. David, Peters,

Leipzig, 1928 (D.).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gustav LEONHARDT,

Harpsichord (Neupert, Bamberg, Germany)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Vienna (Austria) -

maggio 1953 |

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Seymour Solomon

|

|

|

Engineer

|

|

Mario Mizzaro

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Vanguard - The Bach

Guild | BG-532/3 | 2 LPs - durata

37' 00" - 49' 56" | (p) 1954

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Omega Record | OVC

2011/12 | 2 CDs - durata 49' 56" -

37' 00" | (p) & (c) 1993 | ADD

Artemis Classics | ATM-CD-1652 | 2

CDs - durata 49' 56" - 37' 00" |

(p) & (c) 2006 | ADD

|

|

|

Cover Art

|

|

- |

|

|

Note |

|

Billboard, 19 June

1954

|

|

|

|

|

The Kunst

der Fugue as a Work for

Harpsichord

The Kunst

der Fugue, or "Art of

Fugue," is the masterpiece of

Johann Sebastian Bach’s last

years. Bach finished it in a

first version, now known as

the "Berlin Autograph." He

then decided to revise and

expand the music, and engrave

it for publication. He died,

leaving unfinished a colossal

fugue, in which a theme made

up of the letters of his name

entered as the third subject.

The engraving was completed

and the work published by

Bach's sons, in 1750 or 1751,

in a somewhat jumbled form.

In 1752 it was published

again with a preface and

glowing appreciation by the

leading German musical

scholar, F. W. Marpurg, who

said, "in this work are

contained the most hidden

beauties possible to the art

of music." But the tastes of

the times were changing. As

Forkel, Bach's first

biographer, wrote in 1802,

"This work of Bach’s was,

nevertheless, too high for the

great world; it was forced to

withdraw into the small world

inhabited by a few

connoisseurs. This small world

was soon provided with copies;

the plates lay unused, and

were at length sold by the

heirs as old copper."

During the 19th centurly, the

Kunst der Fuge was

published in piano versions by

Czerny and others, but little

performed. The 20th century,

with its increasing interest

in Bach's work, began to

appreciate its greatness.

Several instrumental

arrangements were published,

including an orchestration by

Graeser which used "romantic"

orchestration, one by Vuataz

employing an orchestra

somewhat closer to that of

Bach's practice, and versions

for string orchestra and

string quartet.The theorz

behind them was that since the

work was written in open

score, with no indication of

any instrumentation, it could

be taken up by any

instruments. Both the

architecture and rich

emotional life of the music

emerge from the sounds as

heard, without the feeling

some other arrangements give

of being an "intermediary"

between Bach and the listener,

an addition by a later age.

Gustav M. Leonhardt, who

peforms the Kunst der Fuge

on this record, is a leading

figure in the musical life of

Holland, as harpsichordist,

organist and scholar of Renaissance

and Baroque music. For

some years he was drawn to the

special problem of this

masterpiece of the late Bach.

The result of his study is

contained both in the

performance, and in a

monograph, "The Art of

Fugue - Bach's Last

Harpsichord Work: An

Argument (Martinus

Nijhoff, The Hague, 1952).

Mr. Leonhardt's argument that

this is a harpsichord work may

be summarized as follows.

Frst, it was a known practice

in bot the 17th and early 18th

centuries to publish keyboard

work in open score, especially

those with a complex

pholyphony. Examples are cited

from Scheidt, Frescobaldi,

Froberger and Maichelbeck.

Secoundly, the range of none

of the orchestral or ensemble

instruments, as Bach used

them, corresponds to the range

of any of the voices of the Kunst

der Fuge. Bach. in

writing for instrumental

ensemble, was always a master

instrumentalist, and none of

the characteristic melodic

"shapes" of his ensemble

instrumental writing is found

here. Third, the fugue types

are not those of his ensemble

instrumental fugues, whereas

they are very definitely the

fugue types of his keyboard

works, as in "The

Well-tempered Clavier." Mr.

Leonhardt shows that there is

a striking optical resemblance

between the fugues in this

work and those of the

"Well-tempered Clavier," where

the latter are written out in

open score. The fugues also

have the same "hidden

homophony" of Bach's other

keyboard fugues. Furthermore,

everything in the Kunst

der Fuge is within easy

reach of two hands. Bach made

alterations so that it would

be more playable on the

keyboard. The fact that there

is no "continue bass"

supporting the entrance of the

voices would also make these

fugues different from those of

Bach’s ensemble and orchestral

style. The fact that the bass

voice sometimes rises above

the tenor, with the tenor

becoming the real bass,

indicates to Mr. Leonhardt

that the bass part was not

meant to be doubled at 16-foot

pitch, which would eliminate

the organ from consideration.

Thus, disregarding the limited

clavichord, the harpsichord

becomes the logical

instrument, and Mr. Leonhardt

concludes, "The Art of

Fugue has been written

with an extraordinary

knowledge of the technical

possibilities of ten fingers

on a keyboard. The work does

not only show Bach on his

immense creative height, but

also as the grandiose master

of the keyboard."

Structure

of the Kunst

der Fuge, and

Order of the Fugues

The Kunst

der Fuge may be

described as a colossal set of

fugue variations, consisting

of fifteen fugues and four

canons, all built on the same

basic "motto" theme. Of the

fifteen fugues, four are

"mirror" fugues, in other

words two fugues each followed

by its exact "mirror images."

To this is added a great

unfinished fugue, in which the

name BACH (B flat - A - C - B

natural) appears as the third

theme. The fugues are of every

variety. There are simple,

double, and triple fugues,

fugues with the answer in

contrary motion, fugues in

double counterpoint, fugues in

which the theme appears in

both diminution and

augmentation, fugues in which

all three or four parts are in

contrary motion to each other.

In Gustav Leonhardt's

performance of the Kunst

der Fugue, the musical

text is followed of the

edition of 1750 or 1751, which

was put out by Bach's sons.

Otherwise jowever, this

edition is, as Spitta

describes it, "in dreadful

disorder", with duplications

and additions that obviously

lo not belong in the work. and

so for the orde of the fugues,

Mr. Leonhardt has followed the

"Berlin Autograph", Bach's

earlier version of the work.

To this he has added the fugue

and two canons numbered as 4,

9, and 11, which are not found

in the earlier manuscript but

in the later edition, and

belong to the work as Bach

planned it. Where to place

these is an open question, and

the order chosen is, in

Leonhardt's words, one "of

many possibilities." The

placing chosen here conceives

the work as a great

symmetrical structure, the

nineteen fugues and canons

divided into five main sections

of 4-4-3-4-4, each of which is

also a symmetrical structure;

in other words, a

"microcosmos" within a

"macrocosmos." Within each

section, as in the entire

work, there is at the same

time a sense of continuity and

progressive development, or

"build-up."

The main subject is at first

worked out simply, but already

in a fugue of great power and

beuaty. Then, in the first

group of fugues, the feeling

is enriched by answers in

"French style" dotted rhythm,

while the subject, inverted,

reveals a new "yearning"

emotional feeling. We then

find the subject modified,

appearing in the same fugue in

its natural time and also in

augmentation and diminution.

Then the musical texture,

feeling and structure become

firther enriched as new,

independent and contrasting

themes are used, along with

the main subject. The climax

is reached in two great triple

fugues, one in three voices

and one in four, flanked by

two canons. Then come the two

sets of "mirror fugues", which

Spitta describes as follows.

"From a technical point of

view, they exhibit Bach on a

dizzy pinnacle of eminence. At

a height where existence would

be an impossibility to others,

he breathes with ease and

freedom."

Significance

of the Music

What did Bach

intend in this work? Why, did

he write it in open score? Mr.

Leonhardt's analysis provides

an interesting picture of the

entire Baroque era,

and throws new light on the

particular significance of the

Kunst der Fuge.

The Baroque, as Mr.

Leonhardt describes it, starts

in the period 1580-1630, as a

counter-current to the music

of the high Renaissance,

typified by Palestrina. Its

period of growth is 1630-50,

and its flowering takes place

in 1650-1700. The period of

1700-50, covering most of

Bach's lifetime, in that of Baroque

"refinement", and after 1750

it turns into the light galant

style of Rococo.

The Kunst der Fuge is

a culmination of Baroque

style. Written by Bach near

the end of his life, it was a

conscious attempt by Bach to

halt the movement towards

over-refinement and the galant,

to restore, within the rich

sensuous and technical mastery

reached by Baroque

music, the great qualities at

the "old style", in the form

of deep emotions and

powerfully worked out

polyphony.

This helps to explain both the

deeply moving character of the

Kunst der Fuge, and its

architecture, which Bach

worked out once and then

proceeded to work out over

again on a higher level. It

also explains why he wrote it

in open score, namely, to

emphasize the "old style", the

polyphony, and the basic

lessons of the relationship

and working out of the voices.

It also explains, finally, the

misapprehensions that have

clustered about this work.

Bach's sons and Marpurg, in

their publication of it,

over-emphasized the diadctic

elements, such as "teaching

how to writes fugues", in the

hope that this would help sell

the work. As a result, the

myth has clung about it up to

modern times, that it is an

"abstract" work of

"instruction" in fugue

writing. While Kunst der

Fuge is customarily

translated "Art of the Fugue",

Mr. Leonhardt prefers to

translate in the name as, "Art

of Fugue", thus emphasizing

that it is a work of art in

fugue form, not a set of craft

lessons. And it is just this

"dualism," the combination of

refinement and "spiritual

qualities," he writes, that

"gives this great music its

gripping, even frightening,

atmosphere."

The Great

Unfinished Fugue

The colossal

unfinisched fugue is here

placed at the end. It may be

called a "sketch", since it is

quite possible that Bach would

have not only finished it but

revised it. Yet it is music of

the greatest beauty, and its

sudden breaking off is almost

unbearable. It moves through

three great fugal sections,

each on a new subject, the

third of these being the B A C

H motif. The entry of Bach's

name, and the poignant working

out of it, give the music

almost an autobiographical

quality. For a long time it

was believed not even to

belong to the plan of the

work, since the main of

"motto" subject developed

throughout the Kunst der

Fuge does not appear in

it. But Nottebohm has

discovered that the main or

"motto" subject of the Kunst

der Fuge combines with

the other themes of this great

unfinished fugue so perfectly

that it may be said to have

been implied by them. In other

words, what Bach planned was a

great crowning quadruple

fugue, in which the fourth

entry would be the main or

"motto" subject, in

combination with the other

three.

Style of

Performance - Ornaments

and Rhythm

Mr. Leonhardt

has devoted long study to the

problem of the ornaments to be

used in performance of Bach

and othe Baroque

composers. As he writes, "The

early 18th century was in

Germany not careful in noting

down the ordinary ornaments,

these belonging to the domain

of the performer... The

omission of ornaments was

regarded as a sign of

clumsiness and dullness."

These ornaments consisted of

trills, appoggiaturas, and in

some cases, little connecting

cadenzas. The "safe" procedure

today, of course, is to ignore

this fact, and simply play the

printed notes. But as

Leonhardt points out, far from

this being "faithful" to Baroque

music it results in a

caricature of it. While to

some extent the particular

ornamentation depends on the

taste of the performer, the

specific ornaments and how

they were to be used are amply

described in the literaure of

the mid-18th century, as in

William Friedemann Bach. Also

important is the question of

rhythms. In music of the early

18th century, whenever it was

in "dotted rhythm" or a long

note was grouped with one or

two following short notes, the

long note was beld longer than

written, and the short notes

played as quickly as possible.

This is amply testified to by

writings of J. J. Quantz, W.

Marpurg, and C. P. E. Bach as

well as by examples of Bach's

own music, where in some cases

he writes out exactly how such

rhythms are to be performed.

Mr. Leonhardt's performance of

Contrapunctus VI, in this set,

with its "French style"

rhythms, is an example of this

manner of handling the music.

Such is the difficult and

exacting pathway to a correct

performance of Bach's work,

and of the Kunst der Fuge

in particular. It makes the

music come to life in a way

both exciting and true to the

composer's intentions, far

different from one which adds

to the notes as written "self

expression, romantic style."

As Mr. Leonhardt describes the

early 18th century manner of

peformance, "The executant's

fantasy was concerned with:

ornaments, rhythm, tempo,

phrasing and, in slow

movements mainly, division.

And apart from this equipment,

the performer needed a

refinement of taste and of

musical eloquence in order to

produce the piece in the

right. "Affekt", chosen from a

rich palette of clearly

distinct expressions. In

contrast with the 19th

century, using music as a

means of making music,

regarding it as an object to

manipulate and so always

remaining its master... What

an immensely high standard

performances of Corelli,

Couperin, Bach, Abel, or

Quantz must have attained!"

Gustav

Maria Leonhardt

Gustav M.

Leonhardt, born in 1928 in

Holland, has entered the

select circle of brilliant

instrumentalists who are also

ground-breaking scholars of

Renaissance and Baroque music.

In his student years in

Holland, Switzerland and

Austria he won the highest

honors both for musicology and

performance on the harpsichord

and organ. He is one of the

Achnowledged European masters

of the authentic ornaments and

improvisatory style of Baroque

music. In the spirit of the

old musician-artisans, he is

also an expert on the

construction and design of the

harpsichord and Baroque Organ.

Since 1952 he has been

professor of harpsichord and

musicology at the Academy of

Music in Vienna, dividing his

time between Vienna and the

Conservatory at Amsterdam,

where he teaches as well.

This recording of the Art

of Fugue is the first of

a series of recordings of

Baroque harpsichord and organ

music that will be made by Mr.

Leonhardt, who in an exclusive

Vanguard-Bach Guild, recording

artist- This recording has a

special historic importance,

for it preserves in permanent

form the reading of this work

given by Gustav Leonhardt at

Wigmore Hall in London, the

Brahmsaal in Vienna, and the

Concertgebouw in Amsterdam,

which embodied the fruits of

many years of study of the

problems raised by the music.

These performances, in the

words of the critics, threw a

new and revealing light upon

Bach's great masterpiece,

making it emerge in its full

Baroque grandeur, color and

vitality.

For this recording Mr.

Leonhardt had used a Neupert

harpsichord made in Bamberg,

Germany.

|

|

|

|