|

|

1 LP -

BG-556 - (p) 1957

|

|

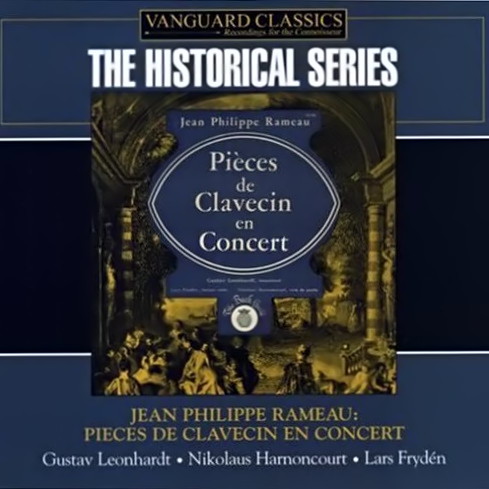

| 1 CD -

ATM-CD-1653 - (p) & (c) 2006 |

|

PIÈCES DE

CLAVECIN EN CONCERT

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Jean Philippe

RAMEAU (1683-1764) |

Premièr

Concert

|

|

7' 52" |

A1 |

|

-

La Coulicam (2'

27") · La Livri (2' 52") · Le

Vézinet (2' 33")

|

|

|

|

|

Quatrième

Concert |

|

7' 24" |

A2

|

|

-

La Pantomime (3'

00") · L'Indiscrète (1' 23") · La

Rameau (3' 01")

|

|

|

|

|

Cinquième

Concert

|

|

8' 24" |

A3 |

|

-

La Forqueray (2'

17") · La Cupis (4' 26") · La

Marais (1' 54")

|

|

|

|

|

Deuxième Concert |

|

12' 23" |

B1 |

|

-

La Laborde (3' 38")

· La Boucon (3'

06") · L'Agacante (1' 31") · Menuet 1

et 2 (4'

08")

|

|

|

|

|

Troisième

Concert |

|

11' 31" |

B2 |

|

-

La Poplinière (2'

40") · La Timide, rondeau 1

et 2 (6' 03") ·

Tambourin 1 et 2 (2'

48") |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gustav

Leonhardt, harpsichord |

|

| Lars Frydén,

baroque violin |

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, viola da gamba

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Brahmssaal,

Musikverein, Vienna (Austria) -

novembre 1955

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Professor Karl

Wolleitner

|

|

|

Engineer

|

|

Franz Plott

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Vanguard - The Bach

Guild | BG-556 | 1 LP - durata 48'

34" | (p) 1957

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Artemis Classics |

ATM-CD-1653 | 1 CD - durata 48'

34" | (p) & (c) 2006 | ADD

|

|

|

Cover Art

|

|

-

|

|

|

Note |

|

Billboard, 6 May 1957

|

|

|

|

|

These

little entertainments of

Rameau are among the more

charming examples of social

music making in 18th century

France. The existence of a

sound tradition in amateur

performance is always a source

of gratification to the

professional composer. During

the 18th century a tradition

of this kind was fairly

widespread both in Europe and

in America. Bach wrote für

Kenner und Liebhaber e.g.

for the professional and the

amateur, for those who knew

music and those who enjoyed

it. (A wise distinction, not

without its point today.) And

nowhere in the 18th century

did the taste of the

cultivated amateur count for

more than it did in France.

These pieces of Rameau have

much in them - either by

instinct (a word Rameau much

admired) or by calculation -

for the pleasure of

performers; for they are

alive, truly and continuously

so, when one shapes the

wonderful patterns of sound

with one's fingers. The

pleasure of the non-performing

listener is necessarily

intimate and immediate, for

this is living room music,

whether performed live or on

phonograph records. This

music, as delicate and as

unpretentious as it must in

essence be, has still no less

noble a purpose than to

delight the ear, charm the

intellect and give pleasure to

the soul.

Flexibility in medium of

performance was not only a

long standing tradition in

Rameau's day, but a certain

freedom in the performer's

exercise of options is

necessarily to the point in

music as sociable and usable

as this. The Title of the work

in its 1741 edition reads as

follows: Pièces

de clavecin, en concertos,

avec un violon ou une flute

et une viole ou un deuxieme

violon (Pieces for

harpsichord in concert with

either a violin or flute and

either a viol or a second

violin). In his introduction (Advice

to Performers) Rameau

further makes it clear that

these are essentially

harpsichord pieces and may be

played as such without the

added parts. ("These pieces

performed on the harpsichord

alone," he writes, "leave

nothing to be desired; one

does not suspect then that

other instruments are

required.") Interestingly

enough, when the other

instruments are added, they

sometimes achieve an

importance in the musical

texture which one would

scarcely suspect in view of

the self-sufficient

harpsichord part. As for the

alternatives in the

instruments to be added, there

was a certain predilection for

the flute among 18th century

amateurs, and, particularly in

France, a marked feeling

against the violin as an

instrument which tended to

dominate if not, indeed,

domineer over its colleagues.

It was not uncommon for the

18th century French composer

to warn violinists to moderate

their tone; and upon occasion

the French violinist was even

enjoined to resist the

brilliant virtuoso

blandishments fashionable

among contemporary Italian

composer-violinists. Gabriel

Guillemain, a contemporary of

Rameau, issued in 1745 a group

of harpsichord pieces "with

violin accompainiment", and

admitted that "he felt

compelled to add that part"

semply "in order to conform to

the present taste." Howewer,

he cautioned that he found the

violin "somewhat too

overbearing" and urged that

the violin part "be performed

quite softly." Rameau's

strictures, if less blunty

expressed, amount to the same

thing. His advice to

performers reads as follows:

"I have

written some small

concerted compositions

for harpsichord, a

violin or flute, and a

gamba or second violin.

Four parts usually

prevail. I thought it

well to publish them in

score, for not only must

the three instruments

blend well togheter, and

the performers

understand each other's

role, but above all, the

violin and gamba must

yield to the harpsichord

and must distinguish

that which is only

accompaniment from that

which is part of the

subject, by softening

their tone still more in

the first case. The long

notes should be played

softly rather than

forcibly, the short

notes very sweetly, and

where the notes follow

each other without

interruption the

rendition should be

mellow."

He then goes

on to say that the pieces

can stand for harpsichord

alone. As for the manner of

converting a violin

part quickly into a

range manageable upon a

flute, Rameau provides the

performer with a few

convenient devices. Where

the violin part goes too low

for the flute, he places an

octave mark (the number 8).

All notes from the number 8

to the letter U (unison) the

flute player simply renders

an octave higher. In rapid

passages, he remarks,

furthermore that "It

suffices to substitute

adjacent notes which are in

the same harmony for those

which descend too low, or to

repeat those which one

considers suitable; except

where one finds small

noteheads on the stems,

almost like specks, which

indicate exactly what should

be played on the flute."

The habit of titling

instrumental pieces is a

long standing one in French

music. While the focus

shifts from generation to

generation, certain general

habits are persistent enough

for us to regard them more

as a matter of national

temperament than as the

peculiarity of a particular

period. Thus among the many

features that mark both

Rameasu and Debussy as

characteristically French in

their keyboard music, is

their common mastery of the

programmatic miniature. Both

are expert craftsmen, in

their way as perceptive in

problems of musical

structure as the Germans.

But abstract design in large

scale musical structures is

not anything either composer

is attuned to

temperamentally. Rameau is

not a fugue-maker in the

Bach manner, anymore than

Debussy is a symphonic

architect in the sense of a

Beethoven. Like everything

else, national musical

temperament is subject to

change; but the 18th century

French notion, so marked in

these pieces of Rameau, that

instrumental music is either

"fit for dancing" (proper

à dancer) or for use

as a clear and delicate

color palette for painting

images in tone, has never

entirely disappeared in

French music.

Notes by Abraham

Veinus, Syracuse

University

Gustav

Leonhardt

Gustav

Leonhardt, the eminent Dutch

harpsichordist, organist and

baroque scholar, typifies the

deeply serious and musically

dedicated artists who have

appeared in Europe alter the

late war. Born in Holland in

1928, he studied at the Schola

Cantorum of Basle, receiving

“cum laude" honors. He then

went to Vienna for iurther

research, specializing in

baroque music, and also

studied conducting under

Clemens Krauss. In 1952 he

became Professor of

Musicology. and also

Harpsichord, at the Vienna

Academy of Music. His teaching

has since been divided between

Vienna and Amsterdam, where he

became professor at the

Amsterdam Conservatory in

1953. He is however in

increasing demand as a soloist

on the harpsichord and organ,

for his mastery of 17th and

l8th century musical style,

combining both a deep feeling

for musical communication with

a unique study of the

ornamentation and notation of

the period. He gave a historic

Sweelinck cycle in

Switzerland. His celebrated

reading, on harpsichord, of

Bach's Art of Fugue,

was presented, to great

acclaim, at Wigmnre Hall in

London, the Brahrnssaal in

Vienna, and the Concertgebouw

in Amsterdam. Also notable

have been his performances of

Bach's Goldberg Variations,

at Vienna, Zurich, Amsterdam

and Leyden. In 1952 his hook,

The Art of Fugue, Bach’s

Last Harpsichord Work,

devoted to a stylistic

analysis of Bach‘s great work,

appeared at The Hague.

|

|

|

|