|

|

1 CD -

VC 7 90800-2 - (p) 1989

|

|

CELLO

CONCERTOS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Carl Philipp

Emanuel BACH (1714-1788) |

Cello

Concerto in A major, Wq. 172 (H439) |

|

19' 19" |

|

|

-

Allegro |

6' 32" |

|

1

|

|

- Largo con sordini, mesto

|

7' 44" |

|

2

|

|

-

Allegro assai

|

5' 03" |

|

3 |

|

Cello

Concerto in A minor, Wq. 170 (H432) |

|

25' 42" |

|

|

-

Allegro assai

|

9' 26" |

|

4

|

|

-

Andante |

9' 47" |

|

5

|

|

-

Allegro assai |

6' 29" |

|

6 |

|

Cello

Concerto in B flat major, Wq. 171

(H436) |

|

24' 46" |

|

|

-

Allegretto |

8' 11" |

|

7 |

|

-

Adagio

|

10' 05" |

|

8 |

|

-

Allegro assai |

6' 30" |

|

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

Anner

BYLSMA, cello & cadenzas

|

ORCHESTRA OF THE AGE OF ENLIGHTENMENT

- Elizabeth Walffisch, Graham

Cracknell, Peter Lissauer, Marshall

Marcus, Julie Miller, Catherine Weis, First

violins

- Susie Carpenter-Jacobs, Nicola

Cleminson, Susan Kinnersley, Catherine

Mackintish, Roy Mowatt, Henrietta Wayne, Second

violins

- Katherine Hart, Annette Isserlis, Martin

Kelly, Rosemary Nalden, Violas

- Timothy Mason, Susan sheppard, Susan

Towb, Richard Tunnicliffe, Cellos

- Judith Evans, Chi-chi Nwanoku, Double-bass

- John Toll, Harpsichord

Gustav LEONHARDT, conductor |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

All Saint's Church,

Petersham, London (England) -

18/20 Novembre 1988

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Tim Handley |

|

|

Balance engineer

|

|

Nicholas Parker

|

|

|

Executive

Producer

|

|

Simon Foster

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Nessuna

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Virgin Classics | LC

7873 | VC 7 90800-2 | 1 CD -

durata 70' 11" | (p) 1989 | DDD |

|

|

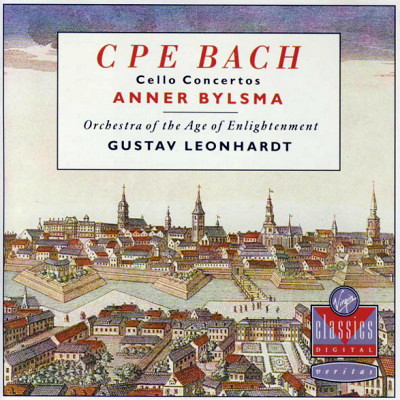

Cover Art

|

|

View of Berlin from

the south: Coloured engraving,

1750 (detail)

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Of Carl

Philipp Emanuel Bach’s

fifty-odd concertos,

thirty-eight date from the

years 1738-68 when he was

court harpsichordist to

Frederick the Great, and of

these, six exist in

different versions for

various solo instruments.

The three cello concertos

recorded here also survive

in versions for harpsichord

and for flute. Unlike his

father, whose keyboard

concertos are all

arrangements of earlier

works for string or wind

instruments, Emanuel Bach is

thought to have made his

arrangements from original

harpsichord versions. We

cannot, however, be certain

of this: of the nine

different versions of the

three works on this

recording, only the cello

version of the A minor

concerto survives in

autograph score. Variants

such as ornamental

elaborations may have arisen

either in the process of

arrangement or in the course

of subsequent transmission,

and such is the idiomatic

nature of the writing in

each case, with passages

rewritten and even expanded

or cut, that it is difficult

to tell which version may

have come first.

Similar uncertainty

surrounds the circumstances

of the composition of these

works. Although they are

thought to date from 1750 (A

minor), 1751 (B flat) and

1753 (A major), we do not

know the particular

occasions for which they

were intended. Bach himself

stated that ‘only a few’ of

his concertos were written

for his own use, and his

music was less frequently

performed at court than that

of the king’s favourites,

Quantz, Graun and Hasse. It

is most likely that these

concertos were intended for

one of Berlin’s flourishing

amateur musical societies,

possibly the Musikalisches

Assemblées organised

by Christian Friedrich

Schale (1713-1800), himself

cellist in the court

orchestra and perhaps Bach’s

original soloist.

The Germany of Bach’s time,

and particularly Prussia

under Frederick the Great,

formed one of the centres of

the European Enlightenment.

Although many of its ideas

were to survive, this period

of enlightened absolutism

was shattered by the French

Revolution and the events

which followed it.

Similarly, much of Bach’s

music represents not so much

a point of departure as a

summation of Baroque style

and ideas. This is

particularly true of the

concertos, for although

there are elements of sonata

form in these works - for

example, in the first

movement of the B flat

concerto recorded here -

they remain essentially

within the Italian

ritornello tradition

perfected by Bach’s father,

with alternating tutti and

solo sections, rather than

an harmonic groundplan,

providing the work’s

dynamic. Much of the

material, particularly in

the solo sections, is

developmental, taking the

form of motivic

fragmentation and

permutation, as in the

extended first movement

ofthe A minor concerto here.

During the solo sections,

the orchestra tosses

fragments of the opening

tutti to and fro while the

soloist plays more lyrical

ideas or figuration.

The concertos also reflect

Bach’s preoccupation with

the Baroque doctrine of the

affects (Affektenlehre).

For Bach, correct use of

affect was a means of

stimulating an edifying and

cathartic experience, an

intention very much related

to Enlightenment idealism. The use of

distinctive melodic

material, often

incorporating wide

intervallic leaps, the

sudden

mood changes and harmonic

coups - all

means to this end - are

hallmarks of Bach’s

style in general. But it is

above all the slow

movements, and particularly

the Largo of the

A major work with its

poignant, expressive

melodic lines coupled to a

wide range of

dynamic indications, that

recall Bach’s own

words from his treatise on

keyboard playing:

A

musician cannot move

unless he too is

moved. He must of

necessity feel all of

the affects he hopes to

arouse in his

audience, for the

revealing of his own

humour will stimulatea

like humour in

the listener... And so,

constantly varying

the passions, he will

barely quiet one

before he rouses another.

Mark

Audus, 1989

|

|

|

|