|

|

1 CD -

VC 7 90806-2 - (p) 1990

|

|

SYMPHONIES

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Carl Philipp

Emanuel BACH (1714-1788) |

Symphony

in D major, Wq. 183/1 (H663) |

|

10' 46" |

|

|

-

Allegro di molto |

6' 14" |

|

1

|

|

- Largo

|

1' 46" |

|

2

|

|

-

Presto

|

2' 42" |

|

3 |

|

Symphony

in E flat major, Wq. 183/2 (H664) |

|

9' 35" |

|

|

-

Allegro di molto

|

4' 14" |

|

4

|

|

-

Larghetto |

1' 27" |

|

5

|

|

-

Presto |

3' 53" |

|

6 |

|

Symphony

in F major, Wq. 183/3 (H665) |

|

10' 37" |

|

|

-

Allegro di molto |

5' 17" |

|

7 |

|

-

Larghetto

|

2' 14" |

|

8 |

|

-

Presto |

3' 04" |

|

9 |

|

Symphony

in G major, Wq. 183/4 (H666) |

|

11' 51" |

|

|

-

Allegro assai |

3' 12" |

|

10 |

|

-

Poco andante

|

5' 05" |

|

11 |

|

-

Presto |

3' 33" |

|

12 |

|

Symphony

No. 5 in B minor for Strings and

Harpsichord, Wq. 182 (H661) |

|

11' 09" |

|

|

-

Allegretto |

4' 01" |

|

13 |

|

-

Larghetto |

2' 26" |

|

14 |

|

-

Presto |

4' 26" |

|

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

ORCHESTRA

OF THE AGE OF ENLIGHTENMENT

- Alison Bury (Leader), Elizabeth

Walffisch, Susan Carpenter-Jacobs, Roy

Mowatt, Peter Lissauer, Marc Cooper, First

violins

- Marshall Marcus, Julie Miller, Pavlo

Beznosiuk, Paull Boucher, Nicola

Cleminson, Frances Turner. Second

violins

- Jan Schlapp, Annette Isserlis, Rosemary

Nalden, Jane Compton, Violas

- Susan Sheppard, Suki Towb, Timothy

Mason, Cellos

- Chi-chi Nwanoku, Double-bass

- Lisa Beznosiuk, Rachel Brown, Flutes

- Anthony Robson, Richard Earle, Oboes

- Jeremy Ward, Bassoon

- Anthony Halstead, Susan Dent, Horns

- John Toll, Harpsichord

Gustav LEONHARDT, conductor |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Abbey Road Studio No.

1, London (England) - Ottobre 1988

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Nick Parker

|

|

|

Balance engineer

|

|

Mark Vigars

|

|

|

Executive

Producer

|

|

Simon Foster

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Nessuna

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Virgin Classics | LC

7873 | VC 7 90806-2 | 1 CD -

durata 54' 15" | (p) 1990 | DDD |

|

|

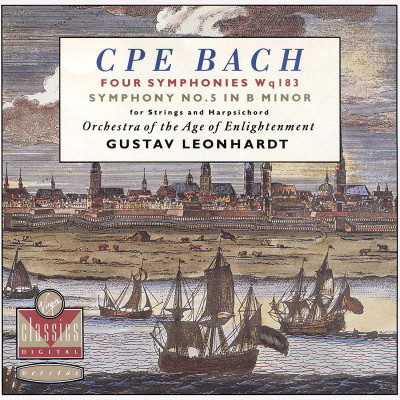

Cover Art

|

|

View of Hamburg

(1750), Engraving by Peter Schenk

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

In

1767 I was summoned to

Hamburg as musical

director, replacing the

late Kapellmeister

Telemann. After repeated

amd most respectful

requests I was granted

leave by the King; and

His sister, Her Royal

Highness Princess

Amalia,

did me the honour of

appointing me as Her

personal Kapellmeister

on my departure.

From

C.P.E. Bach’s

Autobiographical Sketch,

translated by C.D.

Ebeling.

In

March 1768, Carl Phillip

Emanuel Bach

finally left his post as

court harpsichordist to

Frederick the Great in

Berlin and took up his

new position in Hamburg as

musical director

of the city’s five main

churches and Cantor of

the Johanneum School. He had

felt

increasingly stifled during

his thirty years in

Berlin, where the more

conservative music of

Graun, Hasse and Quantz was

preferred. By

contrast, Hamburg, a free

Hanseatic city with

a lively commercial and

intellectual life, offered

an altogether more

stimulating atmosphere.

The music historian Charles

Burney, who

visited Bach there in 1772,

and who left us one

of the most revealing

descriptions of the

composer, wrote of the city

that ‘there is an air

of chearfulness, industry,

plenty, and liberty,

in the inhabitants of this

place, seldom to be

seen in other parts of

Germany’.

Bach’s duties in Hamburg

resembled those

of his late father in

Leipzig. But although he

was responsible for the huge

quantity of music performed in

Hamburg’s churches

throughout

the year, as well as various

teaching activities

at the Johanneum, he was

able to delegate a

certain amount of his work,

and to make use of

existing music where

possible for church

performances. This enabled

him to take on a

wide range of other

activities, in particular

indulging his

entrepreneurial flair for

publishing and marketing his

own music, as

wellas reviving the city’s

concert life by giving

many performances as

keyboard soloist and

director.

Ten of Bach’s nineteen

symphonies date

from his Hamburg years and,

together with his

keyboard music, are among

his finest

achievements. The set of six

string symphonies

Wq.182 (1773) was

commissioned by one of

Bach’s numerous visitors,

Baron Gottfried van

Swieten, the Austrian

ambassador to Berlin

and connoisseur of the arts.

He had travelled

specially to Hamburg to meet

the composer,

and it was through him that

Bach’s music was heard in

Vienna, coming to the

attention of

Mozart and, later,

Beethoven. In his

commission, van Swieten

showed his

understanding of Bach’s

genius by requesting

that he give his musical

imagination a

completely free rein,

‘without regard to the

difficulties of execution

which were bound to

arise’. As a result, the six

works are virtuosic

showpieces, full of

sparkling invention, and

harmonic and dynamic shocks.

All of these

symphonies are in continuous

three-movement

form, with dramatic first

movements and

bipartite, often playful,

finales. The fifth

symphony is the only one in

a minor key, and

also differs in having a

particularly expressive

first movement and a more

dramatic finale,

with its unstable harmonies

producing a feeling

of restlessness.

The four ‘orchestral

symphonies in twelve

obbligato parts’ Wq.183 date

from 1775-6

and, unlike the 1773 set,

were written for

performance in Hamburg.

Scored for pairs of

horns, flutes and oboes,

bassoon, strings and

continuo, they seem to have

been designed to

be heard together, as a

letter written by the

poet Klopstock on 17 August

1776 suggests:

‘How often we wish you were

among us, my

dear Schénborn. Yesterday,

for example, when we heard four

new symphonies by Bach

performed by forty

instrumentalists.’ In their

treatment of the woodwind in

particular these

works look back to the

concerto grosso, but in

almost every other respect

they are forwardlooking.

Even more than in the six

string

symphonies, Bach turns his

back on the

doctrine of unified mood

(Affektenlehre )

towards the more expressive

world of the Sturm

und Drang. Expression, as

the late Carl

Dahlhaus has pointed out,

requires a fusion of

originality and

intelligibility, and it has

often

been said by Bach’s

contemporaries and by

more recent writers, that he

erred toward the

former. Certainly, the

continuous flow of

striking ideas, the use of

harmonic coups, a

wide dynamic range, and

sudden pauses to

engineer distant key changes

all have the

effect of clouding a sense

of form and giving

the impression of an

orchestral fantasia. But

the opening movement of the

D major

Symphony, for example, with

its gradually

intensifying syncopated

first subject, is in

clearcut sonata form. And

the use of a

continuousmovement plan with

often extensive

transitional passages

between first and second

movements, creates a unity

that remains both

challenging and satisfying.

Mark

Audus, 1990

|

|

|

|