|

12

dischi a 78 rŤm - (p) 1953

|

|

| 1 CD -

CD 379 - (c) 2004 |

|

| 2 CDs -

SU 4213-2 - (p) 1953 (c) 2016 |

|

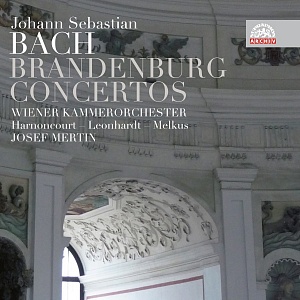

BRANDENBURG

CONCERTOS, BWV 1046-1051

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

BACH (1685-1750) |

Concerto

No. 1 in F major, BWV 1046 |

|

23' 28" |

|

|

-

(without tempo indication)

|

4' 30" |

|

1-1 |

|

-

Adagio

|

3' 46" |

|

1-2 |

|

-

Allegro

|

5' 09" |

|

1-2 |

|

-

Menuetto ∑ Trio I ∑ Polacca ∑ Trio II

|

9' 54" |

|

1-4 |

|

Concerto

No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047 |

|

12' 03" |

|

|

-

(without tempo indication) |

5' 16" |

|

1-5 |

|

-

Andante |

3' 41" |

|

1-6 |

|

-

Allegro assai

|

3' 00" |

|

1-7 |

|

Concerto

No. 3 in G major, BWV 1048 |

|

12' 46" |

|

|

-

(without tempo indication) |

6' 40" |

|

1-8 |

|

-

Allegro |

6' 07" |

|

1-9 |

|

Concerto

No. 4 in G major, BWV 1049 |

|

19' 02" |

|

|

-

Allegro |

8' 05" |

|

2-1 |

|

-

Andante |

4' 40" |

|

2-2 |

|

-

Presto |

6' 08" |

|

2-3 |

|

Concerto

No. 5 in D major, BWV 1050 |

|

22' 43" |

|

|

-

Allegro |

11' 09" |

|

2-4 |

|

-

Affettuoso |

5' 21" |

|

2-5 |

|

-

Allegro |

6' 03" |

|

2-6 |

|

Concerto

No. 6 in B flat major, BWV 1051 |

|

17' 19" |

|

|

-

(without tempo indication) |

6' 36" |

|

2-7 |

|

-

Adagio, ma non tanto |

4' 33" |

|

2-8 |

|

-

Allegro |

6' 02" |

|

2-9 |

|

|

|

|

|

Members of

the WIENER KAMMERORCHESTER and guests

- Edith Steinbauer, violin,

leader (solo in No. 4), viola (2nd viola

in No. 6)

- Alfred Altenburger, violin

- Alice Hoffelner (Harnoncourt), violin

- Eduard Melkus, viola (1st viola in No.

6)

- Nikolaus Harnoncourt, violoncello,

viola da gamba?

- Frida (Krause) Litschauer, violoncello

- Gustav Leonhardt, viola da gamba

- Elisabeth Schaeftlein, recorder

- JŁrg Schaeftlein, recorder, oboe

- Camillo Wanausek, flute

- Helmut Wobisch, trumpet

- Bruno Seidlhofer, harpsichord (solo in

No. 5)

- and others

Josef MERTIN, conductor

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Casino Baumgarten,

Linzer Strasse, Vienna (Austria) -

1950 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio

|

|

studio |

|

|

Executive

producer |

|

Matouö Vlčinskż

|

|

|

Sounf engineer |

|

Karl Wolleitner

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Supraphon |

23291/23302 - (12 dischi, 24

facciate, 78 rpm) | durata 108'

05" | (p) 1953 | Mono |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

ORF "Alte Musik | CD

379 | 1 CD - durata 48' 43" | (p)

& (c) 2004 | AAD Mono | BWV

1048, 1049 & 1051

Supraphon | SU 4213-2 | 2 CDs -

durata 48' 41" - 59' 27" | (p)

1953 (c) 2016 | AAD Mono | BWV

1046-1051

|

|

|

Original Cover

|

|

-

|

|

|

Note |

|

The First

recording with period instruments.

Special thanks to Alice

Harnoncourt, Ingomar

Rainer and Robert Wolf

for the information on the

recording and the members of the

esnsemble.

|

|

|

|

|

On

Josef Mertin's

recordings of the

Brandenburg Concertos

(CDs Supraphon SU

4213-2)

When,

in 1950, post-war Europe,

whose political and cultural

scene had been mercilessly

divided by the Iron Curtain,

was commemorating the 200th

anniversary of the death of

Johann Sebastian Bach

(1685-1750), the festivities

were borne in the spirit of

numerous symbolic

connotations. They were

aimed at re-embracing the

most valuable assets of

conflict-debased German art,

as well as celebrating

Bachís universally

comprehensible musical

language. The festivities

were particularly vigorous

in war-ravaged, divided

Germany and neighbouring

Austria, whose music centres

of Salzburg and Vienna saw

the Bach anniversary as am

opportunity to hold numerous

commemorative events and

concerts. The Bach jubilee

was not overlooked by the

Czechoslovak music publisher

Supraphon, which duly

implemented a project that

would have no parallel in

the country in the years to

follow. Making the best of

the composerís anniversary,

the company utilised the

repertoire in the record

catalogue, the post-war

availability of fledgling

Viennese artists and its

contacts with the musical

circles in the Austrian

capital. In the 1950s.

Supraphon produced a host of

remarkable recordings,

primarily featuring core

Czech 19th- and 20th-century

music, with many of them

catching the attention of

critics and discerning

listeners abroad. From the

late 1950s, Supraphonís

success was increased in

part owing to the engagement

of renowned foreign

conductors and

instrumentalists, including

those hailing from beyond

the Eastern bloc (John

Barbirolli, Jean Fournet,

Antonio Pedrotti, and

others). Nevertheless, at

the time, none of the state

publisherís projects came

into being outside the

country, and without the

participation of

Czechoslovak artists, as had

been the case of the

recording of Bachís

Brandenburg Concertos, BWV

1046-1051 (1718-1721), made

in Vienna in 1950.

The history of the album

started in the heart of the

Broumov Promontory in the

northeast of Bohemia by the

Czech-Polish (until 1945,

Czech-German) border. In

March 1904, Josef Mertin (b.

21.3.1904 Broumov, d.

16.2.1998 Vienna) was born

into a German family living

next to the Benedictine

Monastery. Following his

graduation from the local

grammar school, where he had

received thorough training

in singing, the violin,

piano and organ, and a brief

spell as a music teacher in

his remote native town

(1922-1925), in 1925 he

received a scholarship from

the company Benedikt

Schrollís Sohn and moved to

Vienna in order to study

voice and sacred music at

the Wiener Musikakademie.

While in the Austrian

capital, in 1927 and 1928 he

formed a chamber orchestra

and passed exams in church

music and pedagogy, and in

1928 he graduated as

Kapellmeister from the Neues

Wiener Konservatorium.

Mertin concurrently attended

musicology seminars at the

Universitšt Wien. In 1928,

at the age of 24, he made

his debut with the Wiener

Kammerorchestervereinigung;

from 1932 he conducted Hans

GŠlís Madrigalchor

(1890-1987); and in 1933 he

founded his own instrumental

ensemble, Collegium musicum

Wiener Musikakademie.

At the end ofthe 1920s and

the beginning of the 1930s,

in addition to new

contemporary music and Bach

pieces (the Saint Matthew

Passion, on period

instruments), Mertin also

performed compositions by

Guillaume de Machaut (c.

1300-1377), whose

moderntiine premieres in

Vienna caused quite a stir,

as well as by his beloved

Heinrich SchŁtz. He taught

at the Kapellmeisterschule

and the Neues Wiener

Konservatorium (1928-1938),

the Wiener Volskhochschule

(1932-1938), and at the

Musikakademie (1937-1938).

In 1950 he left the

Konservatorium der Stadt

Wien so as to continue

teaching at the

Musikakademie (1946-1978)

and organ restoring (from

1931 he worked at the

Federal Monuments Office),

to carry out research into

the building of historical

musical instruments and put

together a collection of

early instruments at the

Kunsthistorisches Museum in

Vienna. Evidently the most

intriguing of his activities

were Mertinís experimental

early music performances at

the Hofburgkapelle and the

Albertina gallery (from

1934, he held his own

concert series at the

Festsaal der Graphischen

Sammlung der Albertina). His

achievements in the domains

of music, education,

organisation. restoration

and collecting earned him

the title of Professor, the

Cross of Honour for Science

and Art (1960), the Gold

Medal of Merit for the

University of Music and

Performing Arts in Vienna

(1989), and the Silver Medal

of Merit of the Republic of

Austria (1994).

Before Josef Mertin died at

the age of 93, he could not

only look back fondly at his

long life filled with music

and pioneering work focused

on its early stylistic

periods, he was also able to

observe with pride the

progress of his numerous

pupils (Claudio Abbado,

Mariss Jansons, Zubin Mehta,

and others), many of whom

had been enticed by his

unconventional teaching

methods and imbued with a

passionate ardour for early

music. The New Testamentís

"For many are called, but

few are chosen" (Matthew

22:14) also applied to

Mertinís students, the

majority of whom could only

put up with his not overly

systematic educational

methods for a few lessons.

Yet those who did remain

faithful to Mertinís

apostolic verve and

rccondite pedagogic

techniques embraced

performance of early music

on period instruments and

copies in the post-war

decades so fiercely that

they almost condemned their

teacher's name to becoming a

mere encyclopaedia entry.

The most gifted of Mertinís

pupils in the late 1940s

included the Austrian

violinist Eduard Melkus (b.

1.9.1928 in Baden an Wien),

who in 1946 assumed the post

of concert master of

Mertinís Collegium musicum

and served his teacher as a

faithful and practical guide

through the vieissitudes of

the music scene in Vienna

(from 1951 to 1953, he

studied in Switzerland with

the Vienna-born violinist of

Czech origin Petr RybŠř, a

friend of Bohuslav Martinů).

Melkus also followed in

Mertinís footsteps by

founding early-music

ensembles, Schola antiqua

Wien (1952) and Capella

academica Wien (1965), and

finally, as a professor of

the violin, viola, Baroque

violin and historically

informed early-music

performance at the

Universitšt fŁr Musik und

darstellende Kunst Wien

(1958-1996).

When in the autumn of 1950,

following years spent at the

Schola cantoruin basiliensis

in Basel (1947-1950), the

gifted Dutch organist and

harpsichordist Gustav

Leonhardt (1928-2012)

arrived in Vienna to study

musicology, he immediately

joined Mertinís early-music

seminar attended by a number

of antagonistic talents.

Mertinís students also

included the gifted recorder

player Elisabeth-Liesel

Schaeftlein (1927-1993), a

Graz native and sister of

JŁrg Schaeftlein

(1929-1986), the legendary

oboist of Concentus musicus

Wien (1953). Probably in

1948, she introduced to

Mertin and his disciple

Melkus her gangly compatriot

Nikolaus Harnoncourt

(1929-2016), who from 1948

studied the cello with

Emanuel Brabec at the

Musikakademie. Had

Elisabeth-Liesel Schaeftlein

not done so, the young

Harnoncourt would most

likely have pursued the path

of a solo instrumentalist,

or ďjustĒ a player of the

Wiener Philharmoniker,

performing DvořŠkís and

Straussís music, instead of

becoming one of the major

figures of historically

informed early music

performance of the second

half of the 20th century.

Had it not been for

Elisabeth-Liesel

Schaeftlein, in 1950

Mertinís student team,

extended for the sake of the

imminent recording of the

Brandenburg Concertos with a

group of players of the

Kammerorchester of the

Wiener

Konzerthausgesellschaft, who

for its time and in

comparison with other

Viennese orchestras had an

unusually high proportion of

female members, would have

had to do without the

cellist Harnoncourt.

The talented recorder

student Elisabeth-Liesel

Schaeftlein, the rising

violin star Eduard Melkus,

the hitherto unknown cellist

Nikolaus Harnoncourt and the

subtle Gustav Leonhardt, in

the company of members of

the Wiener Kammerorchester

(l 946), got together in the

studio to make under the

guidance of Melkus a

groundbreaking album of the

Brandenburg Concertos. The

project had been preceded by

the complete recordings made

by Alfred Cortot (1932,

Orchestre de líEcole Normale

de Musique) and Adolf Busch

(1936, Adolf Busch Chamber

Players), as well as

accounts of individual

pieces, including, for

instance, Wilhelm

Furtwšnglerís live

recordings of Brandenburg

Concertos Nos. 3 and 5 with

the Wiener Philharrnoniker

at the Salzburger Festspiele

in 1950. Yet, some two

centuries after Bachís

death, Josef Mertin decided

to take a revolutionary step

and perform the flagship

work - a "showcase of the

composer's instrumental

mastery" (N. Harnoncourt) -

in a chamber formation,

making use of the

instruments and applying the

performance canon of Bachís

own time. "within the

Baroque concerto genre, the

concertos represent an

ultimate apex; with regard

to the instrumentation, they

are true chamber music,

unveiling their value in the

more intimate milieu in

which they were formerly

performed too. Your

gramophone recording (with

its most natural use being

for personal listening in a

private circle) thus

complies with the essential

trait of this music," Mertin

wrote to Supraphon after

listening to the recordings

that were being completed.

A number of the period

instmments employed in

Mertin`s recording of the

Brandenburg Concertos were

from his own collection,

which was also made use of

by the members of the Wiener

Gamben-Quartett (1949):

Melkus, Harnoncourt, Alfred

Altenburger (1927-2015) and

Alice Hoffelner (b.

26.9.1930), who would marry

Harnoncourt in 1953.

Instruments from the

collection were also used by

Gustav Leonhardt, who in

Mertinís recording of the

Brandenburg Concertos played

the viola da gamba

(Brandenburg Concerto No. 6

in B flat major). By the

way, the collection and an

organ built by Mertin

himself (organo di legno)

were indispensable in the

making of the generally

better-known 1954 radio

recording by Paul Hindemith

of Claudio Monteverdiís

opera L'Orfeo, performed by

Melkus and the oldest

generation of the then not

yet named historical

instruments ensemble

Concentus musicus Wien,

helmed by Harnoncourt.

In addition to the

minimalist configuration,

made up of students of

Mertinís early music

performance class and the

members of die Wiener

Kammerorchester, headed by

the concert master Edith

Steinbauer (1901-1996) and

the cellist Frieda

Litschauer-Krause

(1903-1992), the wife of the

orchestraís founder, another

natural facet of the

pioneering 1950 recording

was the adherence to the

original instrumental

structure of Bach`s Kothen

orchestra, including two

recorders in the fourth

concerto, which up until the

1970s were commonly replaced

with traverse flutes.

Specific information about

the instruments played in

the individual Brandenburg

Concertos has not been

preserved, nor has the date

on which the album was made.

Yet Mertinís studio

recording is more than a

mere sonic document of a

revolutionary moment in the

history of performing early

music on modern and period

instruments. Compared to the

later projects of Viennese

provenience - Jascha

Horensteinís, implemented in

September 1954, using

historical instruments

(performed by Nikolaus

Harnoncourt and members of

Concentus musicus Wien), and

the 1957 recording of Felix

Prohaska conducting the

members of the

Kammerorehester der Wiener

Staatsoper - Mertinís

account stands out owing to

his endeavour for the utmost

sonic transparency and

precise leading of the

instrument parts. Mertin

also gave great thought to

the tempos. Even though

Horenstein opted for

markedly faster tempos.

Mertinís account is

strikingly akin to the first

of the series of

Harnoncourtís recordings of

the Brandenburg Concertos

(1964, 1981/1983, 1982).

Mertinís dismissive attitude

to the romanticising

conception of Bachís

orchestral concertos is

boldly audible in comparison

with Furtwšnglerís 1950

album: Whereas Furtwšngler

himself played the piano on

Brandenburg Concerto No. 5

in D major (29:23), Mertin

invited to perform on the

harpsichord the technically

superlative Bruno Seidlhofer

(1905-1982) (22:38).

Furtwšngler turned Bachís

work into a

Classicist-Romantic piano

concerto, while Mertin

returned to the dialogical

character of the Baroque

concerto.

"]osef Mertin was the father

of all the endeavours to

purge Romantic and Baroque

music of romantic deposits

and comfortable tradition,"

the conductor Milan

Turković, bassoonist of

Concentus musicus Wien,

wrote years later. And

bearing cogent witness to

this is even the oldest of

Mertinís (precious few

preserved) studio

recordings, surprisingly

made by the Czechoslovak

label Supraphon. For the

first time since its lirst

release, on 12 shellac

discs, in 1953, Mertinís

complete account (to whose

final recording the (self-)

critical Mertin took

exception and, following the

recordingís completion, he

even offered to make for

Supraphon new recordings,

this time only with

Collegium musicum) is now

being presented to listeners

on CD (in 2004, the year

marking the centenary of

Josef Mertinís birth and the

75th birthday of Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Austriaís ORF

radio station

released a selection of the

Brandenburg Concertos Nos.

3, 4 and 6). Thus, after an

interval of 66 years, music

lovers are offered Mertinís

historically first recording

of the Brandenburg Concertos

in their entirety, as

performed by his ensemble on

modern and period

instruments. The project

serves to pay tribute to

Mertin's visionary approach

and express admiration for

his followers, headed by

Nikolaus Harnoncourt. The

present unique album is also

a proud reminder of their

Czech connections.

Martin

Jemelka

Translation:

Hilda Hearne

Major birthdays are often

very welcome affairs. In

this case, they provide a

suitable occasion to

celebrate two anniversaries,

Josef Mertin's 100th and

Nikolaus Harnoncourt 75th,

whose first gramophone

recording appears on the

present edition.

Of course I realise theat

Josef Mertin (one of the

most modest peole I have

known) would not have

considered this a real

reason to re-issue an

historic recording, least of

all one of his own.

Maybe his description of the

circumstances of this 1950

recording as a "scating over

thin ice" is somewhat

exaggerated, yet it does

represent a memorable step

in the early music revival.

It was prompted by a search

for musical authenticity in

the 1950 Bach year.

Matters that seem

self-evident to us today,

such as the use of recorders

in the 4th concerto (until

the 1970's the use of flutes

was still customary), the

two viola da ganbas in the

6th or the chamber.music

scoring of Bach's "Six

Concerts Avec plusieurs

Instruments" were real

pioneer events in 1950.

The appearance of Eduard

Melkus and of Gustav

Leonhardt, who taught

harpsichord in the 50's at

the Vienna Music Academy,

as gambist in the 6th

concerto only add to the

artistic value of the

production.

As with the restoration of

historic instruments,

greatest care was taken with

the production of this

re-issue. The goal was not

to reproduce the original

sound (almost impossible

anyway) but, in favour of a

wider sound spectrum, to

document the condition of

the original shellac discs

in 2004. Sound filters were

threfore used only seldom

and then extremely

sparingly, and it was

decided not to put movements

together (akthough this

would have been quite

possible) which had been

split up due to the limited

playing time of the discs.

I hope that this recording

from a time far.removed from

ours may not only remind us

that musical interpretations

should always be heard and

judged in the context of

their times, but far more

serve to commemorate a

full-blooded musician who,

until late in life,

tirelessly trained and

influenced several

generations of students

(including myself), a "homo

faber" archetype who

contributedvsignificantly to

the burgeoning of early

music, a warm-hearted,

caring, modest and very

humane person, Josef

Mertin!

Althofen, December 6th, 2004

Bernhard

Trebuch

|

|

|

On

Josef Mertin's

recordings of the

Brandenburg Concertos

(CD ORF 379)

This edition

consists of a transfer onto CD of

12 shellac 78 rpm discs made by

Supraphon in Prague containing

three of six Brandenburg concertos

by Johann Sebastian Bach. The

label on the discs attributes the

recording to "Members of the

Chamber Orchestra of Vienna"

conducted by Josef Mertin and

recorded in 1950. A few

explanations, amendments and

corrections are required

concerning both the time and

circumstances of the recording and

also those taking part.

The early music and authentic

sound movement in Austria in the

twentieth century is closely bound

up with the name of Josef Mertin

(1904-1998) who, until the sixties

and seventies, was considered one

of its most important instigators

and mentors. Born in Braunau in

Bohemia (now part of the Czech

Republic), Mertin arrived in

Vienna in the twenties to study

music. He completed his studies

within a very short period

(1925-28) with diplomas in church

music, voice and conducting from

the then State Academy and the

so-called New Conservatory. In

addition, he attended lectures on

musicology given by Guido Adler

and Rudolf von Ficker at the

university. His experience of

Ficker's combination of

scholarship and musical practice,

togheter with the knowledge and

skill he soon acquired in

instrument-making, did much to

mark Mertin's later work as

musician, teacher and maker.

Numerous concerts and church music

activities during the thirties in

the field of youth music-making

and organ playing (with the

associated rediscovery pf pre-Bach

music which saw the beginning of

Mertin's lifelong dedication to

Heinrich SchŁtz) were interspersed

with the first occasional attempts

to use historic instruments. This

was to be continued after the war

at the Collegium musicum of the

Vienna Music Academy, where Mertin

confronted an international body

og highly-qualified students with

questions concernin the

interpretation of early music,

inspiring them to their own

exploration, as he liked to call

it, which was to spread his

exemplary impetus throughout the

world.

These recordings date from this

period shortly after the war. An

(unfortunately undated) copy of a

letter (Mertin-Archiv, Universitšt

fŁr Musik und darstellende Kunst

in Wien) from the professor to the

"management of the Supraphon

Record Company, Prague" provides

valuable documentation about the

circumstances as well as Mertin's

own particular views of the

recording, a "personal statement

and assessment of the

recentlz-completed recording of

BachŖs Brandenburg concertos".

Mertin assumes that the

necessarily "different nature",

even "apparent lack of uniformity"

in the sound world of each

pieces is inherent to their

differing instrumentation and

design (he discusses only

concertos III, IV and VI which he

apparently received as test

pressings) and thus found the very

different sounds of the individual

recordings acceptable. However

there were other serious problems,

also concerning the editing and

other technical aspects of the

recording, about which Mertin did

notwithhold his criticism: "The

test tape... sounded much more

faithful than the finisched disc.

In my opinion some important

elements in the sound have

disappeared in the cutting

(Frequency range relationships and

balance altered)."

The producer was Mertin's friend

and colleague Karl Wolleitner

(1919-2004) working, according to

our research, in the so-called

"Casino Baumgarten" on the Linzer

Strasse in Vienna's Penzing

district. The processing of the

material however took place

entirely at the Prague factory.

The criticism continue in concrete

detail: "The 3rd concerto has the

most satisfactory 'sound', since

the performers all belong to a

group used to playing together and

the concerto iteself presents the

least problems in terms of sound.

As a recording it is a technical

success, since the composition's

design can be clearly heard. The

concerto has only one dynamic

distorsion... the violins are

unreasonably favoured by their

closer position to the microphone.

The record is good."

"Recorders are added to the

strings in the 4th concerto. These

are real historic instruments, and

on top of that, in the hands of

wind players with particular

stylistic experience. This puts

the quasi-modern string sound at a

disadvantage, lending it an

unflatteringly penetrating

quality." However, all in all the

recording is "well-worth listening

to, and of a higher quality than

other records of this piece up

till now."

Matters start to worsen with the

assessment of the final concerto,

apparently recorded in winter

(February 1950?): "The recording

[of Concerto VI Ed.] suffered from

the heasting failure and contains

more faulty notes than acceptable

even under the circumstances."

(sic!)

In this context, Mertin addresses

a foundamental problem and

handicap to the whole production:

"The Wiener Kammerorchester' was

booked for the recording... this

orchestra is not an ensemble

specialised in early music,

although highly-regarded in Vienna

and working with care and

devotion. The orchestra semply

plays in the same standard and

exemplary way as the Philharmonic

etc. are used to playing. But they

are not early music 'specialiss',

and as a result certain stulistic

wishes cannot be fulfilled with

this ensemble. The 6th concerto

suffers particularly in this

respect... with these players... a

new recording would probably not

produce significantly better

results."

A possible alternative was

offered: "With my Collegium

musicusm as the Vienna State

Academy (where the recorders come

from!) I have built up an ensemble

that plays on actual historic

instruments." String instruments

restored to their original form

are meant here, subsequently

referred to as "short-necked

violins", which proved more

suitable to the demands, since "a

whole host of problems which

otherwise hinder the performance

of early music disappear with the

use of instruments in their

original state."

This stylistic approach of the

whole performance is very

reminiscent today of Paul

Hindemithžs surviving recordings

of his own works such as the

Concerto for Orchestra op.38 and

similar pieces fron the same

period. Mertin's Bach

interpretations also owe something

to the neo-baroque and new

objectivity in the result of his

effort to cleanse and

de-romanticise Bach, to reveal the

compositional steucture. Indeed

Hindemith and Mertin worked

closely together on the 1954

Vienna performance of Monteverdi's

"Orfeo" which so impressed the

young Harnoncourt and for which

Mertin provided a specially-made

"organo di legno".

Meanwhile, the stimulos and

occasions to become involved with

so-called period instruments in

Vienna came most of all from

Othmar Steinbauer (1895-1962),

himself a violin student of Sevcik

who, rejecting the excessive,

highly-individual romantic string

sound as understood by the Hauer

circle, preferred "old"

instruments (even including the

pseudo-Middle Age vielle

newly-designed from iconographic

models but with modern tuning in

fifrhs). The Vienna Gamba Quartet

also made its mark in this field

of activity during the 1950 Bach

year with a sensational

arrangement of the Art of Fugue

(including a completion of the

closing fugue by Eduard Melkus

which remains exemplary today).

Its four members, Alfred

Altenburger, Alice Hoffelner,

Eduard Melkus and Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, who were all closey

associated with Mertin's

Collegium, played on adapted viola

d'amore instruments tuned in

fifths, with the bass gamba being

the only instrument we would

consider historic today.

All this led to the suggestion in

a letter for a re-recording of the

sixth concerto with "new soloist:

1a viola: my best pupil at the

Academy with an original Quinton,

2nd viola: Prof. Steimbauer on an

original old Viennese master

viola; both instruments played

with historic viol bows! 1st

gamba, ny best Academy

gamba-player on an original

instrument using historic bowing

style. 2nd gamba: ditto: also an

outstanding pupil."

Further names included the cellist

Frieda Krause-Litschauer, Bruno

Seidlhofer on the harpsichord and

an unnamed double-bass player from

the Philharmonic, also with an

original instrument. Mertin

requested that the additional

recording sessions be organised

quickly: "The students with whom I

could make this

stylistically faithful recording

have already graduated and are

only available until May."

He mentions that one has got a job

in a "top-rank Swiss orchestra...

one gentleman is going back to

France, another to Holland". This

sets definite time limits as well

as giving some indications about

the partecipants in the recording.

Nikolaus Harnoncourt was among

them, wherther on the gamba as

mentioned above or wherther on the

cello instead of Frieda Litschauer

is no longer certain, as was

Gustav Leonhardt, an excellent

gamba-player in addition to being

a performer on historic keyboard

instruments. He had made his

Vienna debut in 1950 as

harpsichordist and taught at the

Music academy from 1952 before

taking up his position at the

Amsterdam conservatory in 1954. No

doubt he was the gentleman

referred to in Mertinžs letter who

must return to Holland. In the

same year Eduard Melkus ("my best

pupil at the Academy" almost

certainly refers to "the baroquest

violinist" according to

Hindemith's famous dictum) took up

a solo viola position in the

Zurich Tonhalle orchestra, the

"top-rank Swiss orchestra"

mentioned above. Thus the earliest

recording date for the 6th

concerto was to be in the spring

of 1954, and it includes the

"youthful work" of a few players

who were later to become some of

the best performers on the scene!

We may now reconstruct the

definitive list of those taking

part as follows: Edith Steinbauer

(1901-1996), leader as well as

soloist in no. 4 and second viola

in no.6. Eduard Melkus, viola,

also as soloist in no. 6. Nikolaus

Harnoncourt possibly as cellist in

no. 6, but perhaps on one of the

gambas. (That Harnoncourt and very

probably also his future wife,

Alice Hoffelner, were members of

the orchestra can also be

confirmed by the listing of the

complete recording as quasi opus 1

in his official discography.) The

stylistically expert recorder

players in the 4th concerto were

brother and sister JŁrg

(1929-1986) and Elisabeth

(1930-1993) Schaeftlein, the

former soon to become a

long-serving member and leading

light of Concentus Musicus Wien as

baroque oboist. It goes without

saying that the recorders they

used also had nothing in common

with authentic instruments in the

strictest sense. Finally, Bruno

Seidlhofer (1905-1982), later a

renowned piano teacher, is listed

as playing harpsicord continuo.

"The ensemble mentioned here would

also have been better for the

remaining 5th concerto..."

During conversations in later

years Mertin candidly described a

recording of the 5th Brandenburg

(with Bruno Seidlhofer as

soloist), clearly made at the same

time, as "entirely unusuable"; it

never gor beyond the test

pressing, which is also why we

have chosen to ignore it in the

context of this re-issue.

Apparently Hindemith attempted to

direct a recording of the second

concerto with the same team (with

Helmut Wonisch playing trumpet

alongside Elisabeth Schaeftlein on

the recorder). A recording of the

first concerto never seems to have

been attempted.

In an introductory text to a

production of all six concertos

(and thus not directly for this

edition) containing much other

useful information Josef Mertin

also expresses an interesting

thought about his own, carefully

considered relationship to the

recording medium: "The concertos

represent an absolute pinnacle of

achievement in the genre of the

baroque concerto; their

instrumentation in like true

chamber music, whose value is best

revealed in intimate surroundings

such as those in which they were

forst performed. Hnece their

appearance on record (assuming the

most natural use of the record for

personal purposes in intimate

surroundings) corresponds to an

important characteristic of

this music."

May this commemorative re-issue of

his production of the Brandenburg

concertos be granted a suitable

affectionate treatment "for

personal purposes in intimate

surroundings"!

Ingomar Raine

|

|

|

|