|

|

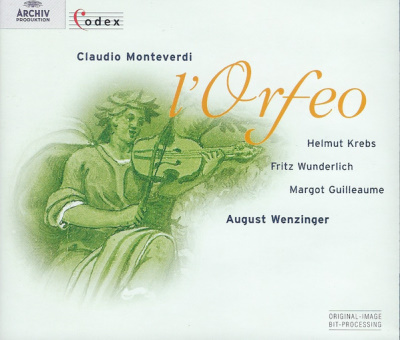

2 LPs

- 14057/58 APM - (p) 1955

|

|

| 2 CDs -

453 176-2 - (p) 1997 |

|

IL SEICENTO

ITALIANO

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Claudio

MONTEVERDI (1567-1643) |

L'Orfeo

(1607) |

|

97' 52" |

|

|

1.

Toccata

|

|

(0' 40")

|

A1 |

|

2.

Prologo: "Dal mio Permesso amato" |

|

(5' 23") |

A2

|

|

Atto primo |

|

(17' 04") |

|

|

3.

"In questo lieto" |

1' 40" |

|

A3 |

|

4.

Coro di Ninfe e Pastori: "Vieni, Imeneo" |

1' 10" |

|

A4 |

|

5.

"Muse, onor di Parnasso" |

0' 50" |

|

A5 |

|

6.

Coro di Ninfe e Pastori: "Lasciate i

monti" |

2' 12" |

|

A6 |

|

7.

"Ma tu, gentil cantor" |

4' 01" |

|

A7 |

|

8.

Coro di Ninfe e Pastori: "Lasciate i

monti" |

1' 08" |

|

A8 |

|

9.

Coro di Ninfe e Pastori: "Vieni, Imeneo" |

1' 07" |

|

A9 |

|

10.

"Ma se il nostro gioir" |

5' 03" |

|

A10 |

|

Atto secondo

|

|

(23' 50") |

|

|

11.

Sinfonia I - "Ecco pur ch'a voi ritorno" |

6' 50" |

|

B1 |

|

12.

"Ahi, caso acerbo" |

8' 44" |

|

B2 |

|

13.

Coro: "Ahi, caso acerbo" |

8' 21" |

|

B3 |

|

Atto Terzo

|

|

(24' 40") |

|

|

14.

Sinfonia II |

1' 00" |

|

C1 |

|

15.

"Scorta da te" |

6' 13" |

|

C2 |

|

16.

Sinfonia III - "Possente spirto" |

9' 26" |

|

C3 |

|

17.

"Ben mi lusinga" |

4' 03" |

|

C4 |

|

18.

Sinfonia II - Coro di Spiriti: "Nulla

impresa per uom" |

3' 48" |

|

C5 |

|

Atto quarto |

|

(12' 31") |

|

|

19.

"Signor, quell'infelice" |

5' 35" |

|

D1 |

|

20.

"Ecco il gentil cantore" |

5' 26" |

|

D2 |

|

21.

Coro di Spiriti: "E' la virtute un raggio" |

1' 30" |

|

D3 |

|

Atto quinto |

|

(13' 44") |

|

|

22.

"Questi i campi di tracia" |

7' 46" |

|

D4 |

|

23.

"Perchè a lo sdegno" |

5' 58" |

|

D5 |

|

|

|

|

Helmut

Krebs, Orfeo

Hanni Mack-Cosack, Euridice

Margot Guilleaume, Musica /

Proserpina

Jeanne Deroubaix, Speranza /

Messaggera

Hildegard Wild, Ninfa

Horst Günter, Plutone

Peter Rot-Ehrang, Caronte

Bernhard Michaelis, Pastore I

Fritz Wunderlich, Apollo / Pastore

II / Spirito II

Peter Offermanns, Pastore III /

Spirito I

Clemens Kaiser-Berme, Pastore IV /

Spirito III

|

Chor der

Staatlichen Hochschule für Musik,

Hamburg

Instrumentalkreis der "Sommerlichen

Musiktage Hitzacker 1955"

Instrumentalisten:

- Ulrich Grehling, Rodolfo Felicani, Violini

piccoli und Violine I

- Dieter Vorholz, Otto Schaernack, Violine

I

- Maria Leonhardt-Amsler, Gertrud

Eggers, Violine II

- Ilse Brix-Meinert, Rosemarie Lahrs,

Viola I

- Robert Haass, Viola II

- Jan Crafoord, Viola da gamba I

- Josef Ulsamer, Viola da gamba II

- Johannes Koch, Angelo Viale, Kontrabaßgambe

- Gustav Scheck, Thea v. Sparr, Blockflöte

- Otto Steinkopf, Heinz Döring, Zinken

(Cornett)

- Harry Barteld, Altposaune

- Gustl Tientz, Adam Rutthoff, Günter

Grätzig, Tenorposaune I, II, III

- Alfred Stönenberg, Baßposaune

- Adam Zeyer, Franz Josef Clemens, Trompete

Continuo:

- Fritz Neumeyer, Gustav Leonhardt,

Cembalo

- Kurt Heinz Stolze, Positiv

- Volkert Lübsen, Positiv und

Regal

- Klaus Storck, Violoncello

- Hannelore Müller, Viola da gamba

- Gerd Ochs, Fritz Seidemann, Chitarrone

- Clothilde Depenheur, Harfe

- Johannes Koch, Kontrabaßgambe

August WENZINGER, Dirigent

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Beethoven-Saal,

Hannover (Germany) - 25/30 Luglio

1955

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Produzione |

|

Dr. Fred Hamel |

|

|

Recording

Engineer

|

|

Harald Baudis

|

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Archiv | 14057/58 APM

| 2 LPs - durata 46' 57" - 50' 55"

| (p) 1955 | Mono

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Archiv Produktion

"Codex" | 453 176-2 | 2 CDs -

durata 47' 32" - 56' 44" | (p)

1997 | ADD | Mono

|

|

|

Cover Art

|

|

-

|

|

|

Note |

|

Sommerlichen Musktage

Hitzacker 1955

|

|

|

|

|

On the 24nd

Febraury 1607 a group of

brilliant and erudite people

assembled at Mantua to

witness the first

performance of the "Favola

in Musica", by the court

musical director of the

noble house of Gonzaga,

Claudio Monteverdi, who was

then forty years of age and

was already one of the most

eminent musicians of

northern Italy. The audience

were justified in expecting

something noteworthly, and

they were not disappointed.

"Orpheus" proved itself to

be neither a pompous

spectacle with music like

those customary at courtly

entertainments, nor a

musically rather arid

melodrama in the style

evolved a few years

previously in Florence, but

a hitherto unique mixture of

the two. True, it was a

drama set word for word to

music, like its Florentine

predecessors, but there was

none of the slavish

subortination of music to

text which had weakened the

earlier operas. Monteverdi

employed all the means

available to him: the old

polyphonic style used side

by side with the new single

voice technique, and all the

wealth of instrumental

effects known at that time.

These various elements were

not brought into play

haphazardly or for their own

sake, as in the old festive

works, but solely for the

purposes of the drama.

"Orpheus" is therefore a

music drama, the first in

musical history, although

from a textual point of view

it is merely a more lyrical

than dramatic Pastoral in a

style common at that time.

Orpheus and Eurydice appear

in the first act among the

carefree shepherds and

nymphs as among their own

kind, and in the second act

a nymph brings Orpheus the

news of Eurydice's death.

The two following acts, set

in the Underworld, contain

virtually all the dramatic

action: the winning over of

Charon, the reunion of

Orpheus and Eurydice, and

the final tragedy of

Eurydice's second death. The

lyrical fifth act, Orpheus'

"Lamento", returns to the

pastoral scene of the first

and second acts, with as

little action.

This division of the work

into two clearly defined

sections exercised a strong

influence on Monteverdi in

his choice of instrumental

colours. He paints the

idyllic scenes on earth,

with their nymphs and

shepherds, by means of the

gentle tones of flutes,

strings, harpsichord and

organ: the Underworld is

depicted by the

awe-inspiring tones of

trumpets and trombones, with

a portative organ as

continuo. The hero Orpheus,

with his characteristic

music, appears in both parts

of the work. The brightness

of the scenes on earth is

characterized by a species

of lyrical recitative,

alternated by short strophic

songs, madrigalesque choric

dances, and lively, rhythmic

orchestral interludes. These

varied elements combine to

create the idyllic

atmosphere of the pastoral

scenes. The happy mood is

destroyed at a blow with the

news of Eurydice's death. At

the entrance of the nymph

bringing the tragic message

in the middle of the second

act it is as though the door

to another world were

opened. The gently flowing

lyrical declamation hitherto

employed is now no longer

able to bear the emotional

burden of the situation. A

more dramatic mode of

expression is called upon,

the vocal line becoming more

forceful, the harmony taking

on a new tenseness, with

astonishingly sharp

dissonances. In short, all

formal considerations are

treated as being of

secondary importance to the

music's primary purpose of

creating in the spectators

the most potent emotional

feeling possible. A

psychological masterpiece

and a highspot of the opera

is the short dialogue of

questions and answers

between the Messenger and

Orpheus, the message of

Eurydice's death itself, and

the despalring cry "Ohimè"

with which Orpheus reacts to

the news. This impassioned

dramatic declamation

(especially impressive in

the narration of Eurydice's

death, in the lament of

Orpheus which follows it, to

the expression of his

anxiety on behalf of his

regained and then

irrevocabily lost Eurydice,

and in his final "Lamento"

in the fifth act) is

alternated, in the scenes in

Hades, with pathetic

choruses and solemn, ominous

instrumental interludes. a

born musical dramatist,

Monteverdi knew that a

continuous state of

emotional tension would tire

the soectators. He therefore

introduced not only

straightforward declamatory

passages into the

recitative, but also on out

and out comic part, that of

the ferryman Charon in the

third act. Even Orpheus'

great vocal solo "Possente

spirto, e formidabil nume",

in which he employs all his

wonderful art as a singer,

does not disturb the rough

Charon from his stupid

self-satisfaction.

Monteverdi's "Orpheus" ist

the earliest real music

drama, that is to say the

first work in which the

music is entirely one with

the dramatic idea, but both

the music and the idea

itself are far removed from

anything to which modern

audiences are accustomed,

and it is necessary to make

an effort to see the work

from the viewpoint of the

period at which iy was

written if the full measure

of its greatness is to be

appreciated. All that later

generations have achieved

with powerful

musical-dramatic situations,

novel instrumental effects

and huge orchestral forces,

had its origins in the

achievement of the operatic

genius Claudio Monteverdi,

who used all that he found

serviceable of the resources

available to him, with the

enthusiastic approval of his

more enlightened

contemporaries. We only need

to understand how to listen

to his music - then it is a

revelation!

Anna

Amalie Abert

|

|

|

|