|

Columbia

- 1 LP - 33QCX 10025 - (p) 12/1953

|

|

| Columbia

- 1 LP - 33CX 1102 - (p) 12/1953 |

|

Warner

Classics

14 CDs - 0190296739200 - (p) & (c)

2021 |

|

| Wolfgang Amadeus

Mozart (1756-1791) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Quartetto

n. 14 in sol maggiore, KV 387 |

|

30' 13" |

|

-

Allegro vivace assai

|

7'

23" |

|

|

| -

Allegretto |

8' 37" |

|

|

-

Andante

cantabile

|

7' 50" |

|

|

-

Molto allegro

|

9' 23" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Quartetto n. 15 in re

minore, KV 421 |

|

28' 19" |

|

-

Allegro moderato

|

7' 26" |

|

|

| -

Andante |

5' 53" |

|

|

| -

Allegretto |

4' 18" |

|

|

| -

Allegretto

ma non troppo |

10' 42" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

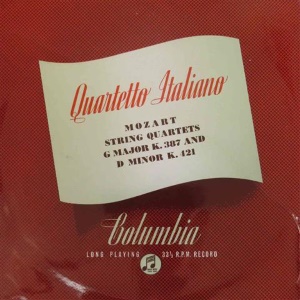

QUARTETTO

ITALIANO

- Paolo Borciani, Elisa Pegreffi, violino

- Piero Farulli, viola

- Franco Rossi, violoncello

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione |

|

Milano (Italia) -

4/6 luglio 1953 (KV 387) &

3/4 luglio 1953 (KV 421) |

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Columbia | 33QCX 10024

- (Italy) | 1 LP | (p) 1953 |

Mono

Columbia | 33CX 1102 - (England)

| 1 LP | (p) 1953 | Mono

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Warner Classics

| 0190296739200 | 14 CDs

[CD2] - 58'

35" | (p) &

(c) 2021 |

Mono |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Unlike

Beethoven, Mozart

was a facile

composer, but the

six quartets (Op.

X, 1783-1785) he

dedicated to Haydn

were "the fruit of

long and arduous

toil": thus he

describes them in

his

dedication.

"During your

last stay in

this capital,

Vienna, "he

continues, "you

yourself my dear

friend,

expressed to me

your approval of

these

compositions.

Your good

opinion... leads

me to hope

that you will

not consider

them wholly

unworthy of

your favour."

(The

dedication is

in Italian: I

have partly

availed myself

of Emily

Anderson's

translation.)

Two powerful

motives joined

forces in

Mozart's mind

in order to

create these

conscientious

and conscious

masterpieces.

One was the

thought of the

dedicatee, to

whom they owed

much (and who,

in his turn,

came to owe

much to them).

The other was

Mozart's

realization of

the fact that

the string

quartet is a

supreme

challenge as

well as a

supreme

responsability:

superficially

the least

"effective" of

all musical

media, it can

be,

spiritually,

the most

telling. Sure

enpugh,

without the

sage yet

fullblooded

serenity of K.

387 (the first

of the "Haydn"

set),

and without

the deep yet

optimistic

tragedy of K.

421 (the

second), two

central events

in the story

of the human

mind would

have remained

untold.

QUARTET

IN G MAJOR, K.

387

The first

movement's

forthright first

subject shows a

duality of forte

and piano

which Mozart had

developed

into a highly

characteristic

means of

structural

expression, even

though he

probably "had

it" from Johann

Christian Bach.

In the latter

part of the

theme, the dual

approach expresses

itself in a

different way,

i.e. texturally

rather than

dynamically: the

phrases are

distributed

between the

instruments. The

little chromatic

semiquaver

figure in the

second subject

does not really

consist of two

notes that have

the same rights

and privileges;

the upper note

is merely

"coloured" by

the lower one in

order to keep up

the movement

(thus remindings

us of the origin

of the term

"chromatic": khroma

means colour).

The principle of

thematic

distribution

between the

instruments is

maintained both

in this theme

and in the

development,

which the three

upper

instruments

introduce with

three

consecutive, and

as it were

cumulative,

variations on

the first

subject.

In

the minuet,

the

afore-mentioned

dynamic

dualism is

compressed

within the

narrowest

possible

space:

successive

notes

alternate

between forte

and piano,

as indeed they

had already

done at the

end of the

opening

movement's

second

subject. The

displacement

of accent thus

achieved

results, in

effect, in a

temporary 2/4

time, all the

more so since

the opening

bars' first

beats ean

easily be

heard as

upbeats.

The

slow movement

is in abridged

sonata form,

which is to

say that a few

modulating

bars take the

place of the

development.

(A "quick"

example of

this forms is

the Figaro

Overture.)

In

structure and

texture alike,

the finale is

the most

original

movement:

alternations

between the

"learned" and

the "galant"

styles between

fugue and

accompanied

melody, are

built into

what thus

becomes an

unprecedented

sonata arch,

which iteself

forms a

precedent for

the last

movement of

the "Jupiter"

Symphony

(1788); the

two finales

share,

moreover,

their art of

developing an

in iteself

meaningless

tag (the theme

of the first

subject) into

an

overshelmingly

meaningful

form of the

sybtlest

complexity.

The

recapitulation

emits the

opening a

device

foreshadowed

as early as

the famous D

major Violin

Concerto, K.

218, of 1775.

QUARTET

IN D MINOR, K.

421

The

first

subject's

weighty bass

sets the pace

as well as the

mood of the

first

movement.

Significantly

enough, the

key of this

mood, D minor,

is that of

Mozart's first

Piano Concerto

in the minor

mode the

celebrated K.

466 of 1785.

The second

subject, in

the relative

major, views

the tragedy of

the first in

perspective.

It consistes

of a theme and

one variation

whose triplets

offer the

first fiddler

a legitimate

opportunity

for a touch of

brillance. Not

that the

triplets are

limited in

their formal

function: they

help to build

the closing

section of the

exposition,

whence they

radiate into

the

development.

The

recapitulation's

variations on

the second

subject

succeed in

uniting the

(tonic) minor

mood with a

major

emotional

liberation.

The "cello

receives the

lion's share

of the coda

and justifies

the metaphor

in the

process.

Although

the slow F

major movement

is in ternary

(A-B-A)

form, the

contrasting

middle section

is strctly

thematic; its

central

portion is, in

fact,

an A flat

major

variation on

the movement's

theme.

As

opposed to its

playful trio,

the minuet is

extremely

serious: metre

and lay-out

apart, it has

severed itself

from the dance

form. The

threads of the

chromatically

descending

bass are taken

up by the

fiddles in the

middle

section.

The

finale

consists of

four

variations and

a quicker coda

on a

siciliana-like

tune which

derives from

Haydn's String

Quartet, Op.

33, No. 5.

Rhythmically,

the most

complex

variation

- and

one of the

most

complicated

structures in

the whole of

Mozart - is in

the second.

It is what one

would nowadays

call

"polyrhythmic",

the viola

being the only

instrument

which plays

throughout the

rhythm of the

time signature

(6/8). To all

intents and

purposes, the

first violin

plays in

triple time,

while the

second, which

has the really

knotty part in

that it has to

be both

flexible and

decisive,

pursues an

unperturbed

quadruple

metre. The 'cello,

finally, may

be said to

prefer a

semple duple

time. The

third

variation

contains one

of whose viola

solos (in a

dialogue with

the two

fiddles which

play in octave

unison) which

remind one, by

way of

retrospective

illusion, of

Mozart's own

viola playing:

while he was

not

particularly

enamoured of

the violin, he

loved to play

the viola; and

to complete

our aural

illusion with

historical

accuracy,

Haydn and

Dittersdorf

would be

playing the

violin unison!

The fourth

variation is

in the major,

but the

recapitulatory

coda returns

to the minor,

until at the

very end the

major gains

the upper hand

not without a

warning B flat

in the final

cadence.

Note by Hans

Keller

(Columbia

33CX 1102)

|

|

|