|

|

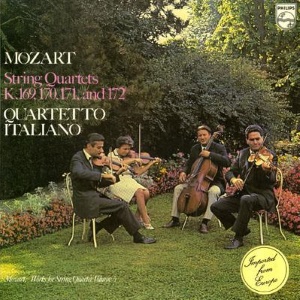

Philips

- 1 LP - 6500 644 - (p) 1973

|

|

| Philips

- 8 CDs - 416 419-2 - (c) 1990 |

|

| Wolfgang Amadeus

Mozart (1756-1791) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| String

Quartet No. 9 in A major, KV 169 |

|

15' 20" |

|

-

Molto allegro

|

3' 22" |

|

|

| -

Andante |

7' 16" |

|

|

| -

Menuetto |

3' 06" |

|

|

| -

Rondeaux (Allegro) |

1' 36" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| String

Quartet No. 10 in C major, KV 170 |

|

15' 38" |

|

-

Andante

|

4' 48" |

|

|

| -

Menuetto |

3' 05" |

|

|

| -

Un poco adagio |

5' 12" |

|

|

| -

Rondeaux (Allegro) |

2' 33" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| String

Quartet No. 11 in E flat major,

KV 171 |

|

16' 29" |

|

-

Adagio - Allegro assai

|

5' 56" |

|

|

| -

Menuetto |

2' 52" |

|

|

| -

Andante |

4' 48" |

|

|

| -

Allegro assai |

2' 53" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| String

Quartet No. 12 in F flat major, KV

172 |

|

15' 43" |

|

-

Allegro spiritoso

|

4' 01" |

|

|

| -

Adagio |

5' 03" |

|

|

| -

Menuetto |

3' 03" |

|

|

-

Allegro assai

|

3' 36" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

QUARTETTO ITALIANO

- Paolo Borciani, Elisa Pegreffi, violino

- Piero Farulli,

viola

- Franco Rossi, violoncello

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione |

|

La

Tour-de-Peilz

(Svizzera)

- 23

luglio / 3 agosto

1972 |

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Vittorio

Negri | Joost Hummeling

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Philips

| 6500

644

| 1

LP | (p) 1973

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Philips | 416 419-2

| 8 CDs - (2°,

11-14; 3°, 1-4, 5-8, 9-12)

| (c) 1990 | ADD

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Mozart

composed these four

quartets in the late

summer of 1773 in Vienna,

where he and his father

had followed their master,

the Archbishop of

Salzburg. Mozart Was then

a lad of 17, but he was

already a highly

accomplished composer,

with many

astonishingly mature

works to his credit.

These string Quartets,

although still only

the work of a

teenager, are more

than comparable with

similar works by

contemporaries of

twice and thrice his

years. In a way they

are still stepstones

on the way to greater

things, yet

nevertheless, being by

Mozart, they are still

well worth our careful

attention. Formally

they are highly

accomplished and

display a surprising

diversity of

structure, non two

being alike, even in

the overall pattern of

their movements.

The

amazing thing about the

youthful Mozart is how

very up-to-date he was

formally, from the beginning

of his creative

career. There is

never nything

old-fashioned in his

music; he seems to

have known from the

beginning exactly

what the new "sonata

form" was, and how

to use it. And

melodically, of

course, he was

always in the very

forefront of taste;

probably his various

journeys to Italy

did this for him.

Where many of his

older contemporaries

just managed to get

to Italy once in

their lives or even

not at all. Mozart

went there several

themes and was

continually hearing

new Italian operas,

an a

result he was always

aware of every

little shift in

melodic patterns.

Yet he was still

master of the old

learnead

counterpoint and

could use it

effortlessly, when

the opportunity

arose. With all this

in mind, left us

look ak these four string

quartets, composed

in the city which

in his time was

rapidly becoming

the musical

capital of the

world, although

still paying much

lip

service to the

music of Italy.

QUARTET

IN A, K. 169

This

is the most

"regular" in

form of the

four quartets

on this

record. It

opens with a

brisk Allegro

in sonata form

- but even

here Mozart

springs a

surprise on

us, for his

middle section

is more

discursion

than

development

and is based

on a

completely new

subject,

although his

main subject

does return in

F sharp minor,

in a sort of

false

recapitulation,

before the

real

recapitulation

begins in the

tonic.

The

slow movement

is largely a

solo for

the first

violin,

accompanied by

the lower

strings; to us

it seems to

breathe an

elegiac

beauty, but it

was probably

already too

chromatic for

some of the

older

music-lovers

of Mozart's

time. "So

gifted is this

young man,"

wrote one of

his

contemporaries,

"that his

music is

almost too

difficult and

must be heard

many times

before it can

be fully

understood" -

and this in an

age when music

was rarely

heard twice.

But all is

tonic-and-dominant

light in the

following Menuetto

and trio; even

the most

die-hard old

music-lover

must have

enjoyed these

straightforward

tunes and

crisp rhythms.

And then the

rondeau

finale! Such

gaiety! Such

vitality! Such

clarity of Rococo

formal grace!

Even J.C.

Bach, the

Prince of the

Galant, could

not outdo such

enchantment as

this, from

this most

sincere of his

young

admires...

QUARTET

IN C,

K. 170

Here,

in the second

quartet,

Mozart

immediately

surprises us

by beginning,

not with a

sonata-form Allegro,

but with an Andante

con variazioni.

The theme is

four-square -

eight bars

first and

then,

oddly, nine

bars. Who sald

that the

Galant and

Classical

composers were

always forming

fours? Here is

immediate

contradiction,

Mozart handles

the ensuing

variations

very cleverly,

giving most of

the fun yo his

fist fiddle,

but keeping up

the interest

throughout,

until he

suddenly

repeats his

theme, in

toto, at

the end -

always a

satisfactory

touch.

Then

comes the

minuet,

starting very

formally, but

taking on a

strange

chromatic

quality in the

second strain;

the trio

almost

preechoes

Beethoven.

Mozart then

surprises us

again, with a

deeplyfelt Adagio;

once again,

the first

fiddle has

most of the

melody,

although

strangely

enough the

viola becomes

quite

prominent,

after the

double-bar.

Another gay

rondo finale

follows; it is

still very

much of the

French

"rondeau"

pattern, with

the main theme

returning each

time in the

tonic.

QUARTET

IN E FLAT, K.

171

Again

a slow opening

(Adagio).

But this time

Mozart is

playing a very

clever trick,

for he has

really written

a sonata-form

first

movement,

enclosed

between two

short slow

movements. The

result is a

pattern of

great

fascination.

Perhaps the

answer lies in

the opening of

the Allegro

assai which is

deceptively

fugal - for

eight bars,

after which it

becomes rather

more

sonata-like,

although even

so it is

formally very

odd. Had

Mozart an

"Ancient-style"

French

overture in

mind in

opening thus?

The

minuet and

trio are very

straightforward

and tuneful.

Then comes an

Andante

of great charm

- and later of

learned

counterpoint,

with first and

second violins

imitating each

other amid

deft touches

from the lower

strings; here

is some

exquisite

string-quartet

writing. And

then an almost

symphonic

finale, which

would come off

almost as well

on a full

string band as

on a string

quartet.

QUARTET

IN B FLAT, K.

172

Mozart's

musical

thought seems

to have been

growing

increasingly

symphonic, as

he wrote these

quartets -

symphonic,

that is, with

operatic

connections.

The first

movement of K.

172 is very

like that of

an Italian

sinfonia

avanti l'opera

- the same

bold opening coup

d'archet;

the gracious,

feminine

second

subject; the

lyrical

discursion

after the

double bar,

rather than a

true

development,

and lastly the

neat, regular

recapitulation.

With the slow

movement we

really are in

the opera

house, for its

main subject

is very

closely

related

thematically

to the

Countess's

song "Porgi

amor" in

"Figaro." The

minuet is more

intimate and

unusual in

that it begins

on that often

despised

instrument,

the viola, and

has a trio in

G minor. And

then comes the

liveliest of

2/4 finales,

full of jolly

tunes and

sprightly

rhythms

Mozart's

invention runs

high and he

tosses the

ideas away

with the same

careless

bounty thet he

does in his

pure

entertainment

music. The

work as a

whole is a

masterpiece

more than

worthy to hold

an honoured

place with the

more familiar

string

divertimenti,

K. 136-138.

Charles

Cudworth

QUARTETTO

ITALIANO

The

Quartetto Italiano is

deservedly one of the

most renowned quartets

of our time. It was as

long ago as 1945, soon

after completing their

studies, that Paolo

Borciani, Elisa

Pegreffi, Piero

Farulli, and Franco

Rossi, resisting the

tempting promise of

individual careers as

soloists, decided to

pool their youthful

enthusiasm and musical

talent and devote

themselves to the

difficult but

satisfying art of

playing chamber music

really well. By 1947

the group had

established a firm

reputation in the

musical press and

begun giving concerts

outside Italy. In 1951

they visited the

United States for the

first time, and it was

soon apparent that

their devotion to

their music and the

impeccable standards

of performances they

had set for themselves

were earning them fame

as well as

satisfaction. Over the

years since 1945 they

have remained

together, a rare

example of teamwork in

music.

To list the group’s

wide-ranging

activities in more

than 25 years is

pointless: they have

done everything one

might expect of one of

the world’s finest

quartets. They have

given hundreds of

concerts all over

Europe and in the

United States; they

are regular

partecipants in the

chamber-music concours

of many countries; and

they have played and

are in constant demand

at the world’s great

music festivals.

Outside the concert

circuit the members of

the quartet teach

chamber music at both

the Royal Academy of

Music in Stockholm and

the Conservatoire in

Vienna.

In addition to the

many words of praise

bestowed on them –

after their first

concert in New York,

Virgil Thomson, the

distinguished critic

of the “New York

Herald Tribune,”

called them “the

finest quartet,

unquestionably, that

our century has known”

– they have been

publicy honoured by

the President of Italy

as a more tangible

recognition of their

outstanding artistic

services over the

years to Italy in

particular and the

world of music in

general.

|

|