|

|

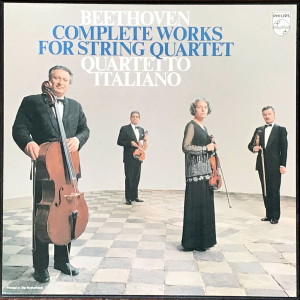

Philips

- 10 LPs - 6747 272

|

|

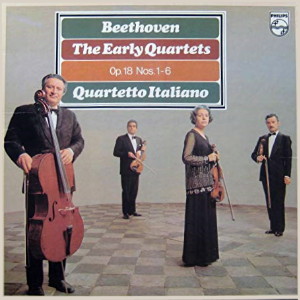

| Philips

- 3 LPs - 6998 025 |

|

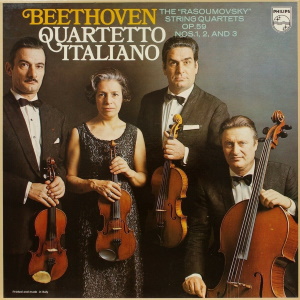

| Philips

- 3 LPs - 6998 017 |

|

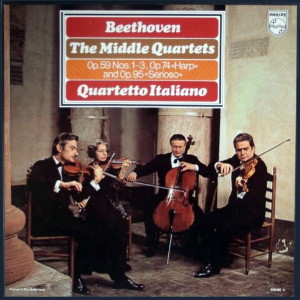

| Philips

- 3 LPs - 6703 085 |

|

| Philips

- 4 LPs - 6707 008 |

|

Philips

- 4 LPs - 6998 022

|

|

| COMPLETE WORKS FOR

STRING QUARTET |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ludwig van Beethoven

(1770-1827) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE

EARLY QUARTETS

|

|

|

|

|

| -

String Quartet No. 3 in D

major, Op. 18 No. 3 |

LP

1 - Philips

6500 181 - (p) 1972

|

|

26' 08" |

|

| -

String Quartet No. 1 in F

major, Op. 18 No. 1 |

LP

1 - Philips

6500 181 - (p) 1972

|

|

28' 05" |

|

| -

String Quartet No. 2 in G

major, Op. 18 No. 2 |

LP

2 - Philips

6500 646 - (p) 1975

|

|

25' 12" |

|

| -

String Quartet No. 4 in C

minor, Op. 18 No. 4 |

LP

2 - Philips

6500 646 - (p) 1975

|

|

25' 04" |

|

| -

String Quartet No. 5 in A

major, Op. 18 No. 5 |

LP

3 - Philips

6500 647 - (p) 1973

|

|

29' 26" |

|

| -

String Quartet No. 6 in B flat

major, Op. 18 No. 6 |

LP

3 - Philips

6500 647 - (p) 1973

|

|

27' 20" |

|

| THE

MIDDLE-PERIOD QUARTETS |

|

|

|

|

-

String Quartet No. 7 in F

major, Op. 59 No. 1 ("Rasoumovsky"

No. 1)

|

LP

4 - Philips

6747 139 - (p) 1974 |

|

40' 29" |

|

| -

String Quartet No. 8 in E

minor, Op. 59 No. 2 ("Rasoumovsky"

No. 2) |

LP

4/5 - Philips

6747 139 - (p) 1974 |

|

38' 19" |

|

| -

String Quartet No. 9 in C

major, Op. 59 No. 3 ("Rasoumovsky"

No. 3) |

LP

5 - Philips

6747 139 - (p) 1974 |

|

32' 01" |

|

| -

String Quartet No. 10 in E

flat major, Op. 74 "Harp" |

LP

6 - Philips

6500 180 - (p) 1971 |

|

32' 34" |

|

| -

String Quartet No. 11 in F

minor, Op. 95 "Serioso" |

LP

6 - Philips

6500 180 - (p) 1971 |

|

20' 22" |

|

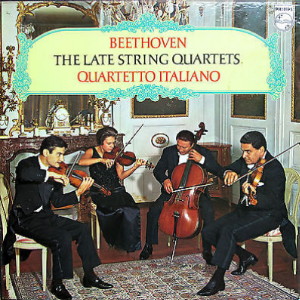

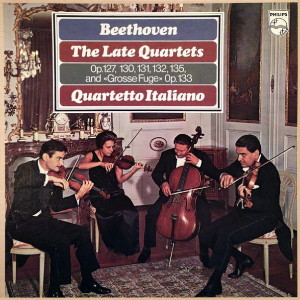

THE

LATE QUARTETS WITH "GROSSE FUGE," OP.

133

|

|

|

|

|

| - String Quartet

No. 12 in E flat major, Op.

127 |

LP

7 - Philips

839 745 - (p) 1968 |

|

38' 04" |

|

| - String

Quartet No. 16 in F

major, Op. 135

|

LP

7 - Philips

839 745 - (p) 1968 |

|

25' 20" |

|

| - String

Quartet No. 13 in B flat

major, Op. 130 |

LP

8 - Philips

839 795 - (p) 1969 |

|

42' 50" |

|

- "Grosse

Fuge" in B flat major, Op.

133

|

LP

8 - Philips

839 795 - (p) 1969 |

|

18' 52" |

|

- String

Quartet No. 14 in C sharp

minor, Op. 131

|

LP

9 - Philips

802 915 - (p) 1969 |

|

42' 30" |

|

- String

Quartet No. 15 in A minor,

Op. 132

|

LP

10 - Philips

802 806 - (p) 1968 |

|

47' 10" |

|

|

|

|

|

QUARTETTO

ITALIANO

- Paolo Borciani,

Elisa Pegreffi, violino

- Piero Farulli, viola

- Franco Rossi, violoncello

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione |

|

Théâtre

Vevey, Vevey (Svizzera)

La

Salle des Remparts,

La Tour-de-Peilz (Svizzera)

Musica-Théâtre,

Salle de Musique, La-Chaux-de-Fonds

(Svizzera) |

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Vittorio Negri |

Tony Buczynski, Willem van

Leewev, Ko Witteveen, Joost

Humeling, Gerard Janszen,

Frans von Dongen

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Philips | 6747

272 | 10 LPs | (Complete

Works for String Quartets)

Philips | 6998 025 | 3 LPs |

(The Early Quartets)

Philips

| 6998 017 | 3

LPs | (The

Middle-Period

Quartets)

Philips | 6703

085 | 3 LPs | (The

Middle-Period Quartets)

Philips

| 6707 008 | 4 LPs | The

Late Quartets)

Philips

| 6998 022 | 4

LPs | (The Late

Quartets) |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Philips | 426 046-2

| 3 CDs (54' 02" - 47' 25" - 57'

28") | (c) 1989 | ADD | (The

Early Quartets)

Philips | 420 797-2 | 3 CDs (40'

29" - 58' 51" - 64' 35") | (c)

1989 | ADD | (The Midle-Period

Quartets)

Philips | 426

050-2 | 4 CDs (63' 45" - 62'

00" - 42' 22" - 47' 10") | (c)

1989 | ADD

| (The Late Quartets)

|

|

|

Note |

|

Ripubblicazioni

in cofanetto

dell'opera per

quartetto

d'archi di Beethoven.

|

|

|

|

|

BEETHOVEN:

COMPLETE WORKS

FOR STRING QUARTET

THE EARLY

QUARTETS

In considering

Beethoven's

artistic

creative

processes, a

certain area

might well be

reserved for

determining how

his own ideas

and personal

style were to be

reconciled with

the various

requirements of

difficult

musical genres.

It is quite

remarkable that

Count Apponyi’s

request to

Beethoven in

1795 to write a

string quartet

provided at

first only an

incentive to

write something

in a related

genre - in fact

the String

Quintet Op. 4.

The special

regard - not to

say respect -

for

quartet-writing

is made clear in

Beethoven’s

letter of July

13, 1808 to the

publishers

Breitkopf &

Härtel:

"...

I have

turned a single

sonata of mine

into a quartet

for stringed

instruments for

which people

were so

earnestly asking

me, and I know

for certain that

it would not be

easy for anyone

to do it better

than I

have done..."

In

the realm of the

string quartets

the spirit of

Mozart,

transmitted

through Haydn,

which Beethoven

had come to

Vienna to

receive, is

clearly

discernible.

Emanuel Aloys Förster

also exercised a

strong

influence. Some

of Beethoven’s

transcripts,

still extant,

make it clear

that he must

have made a

study in depth

in particular of

Mozart‘s Quartet

in A, K. 464 and

Haydn’s Quartet

in D, Op. 20 No.

4. The inclusion

of six quartets

in a single opus

number - in

Beethoven’s case

Op. 18 - is in

itself a general

indication of

Mozart and Haydn

as models. More

precisely,

Beethoven’s

Quartet Op. 18

No. 5 shows

clear affinities

with, if not

direct

reminiscences of

the Mozart

quartet

mentioned above

- in the common

key of A major

and, in the

overall

structure, the

reversal of the

middle movements

and the use of a

movement

consisting of a

theme and

variations, a

particularly

characteristic

form for

Beethoven

himself. The

minuet of

Beethoven’s

quartet reveals

very personal

characteristics;

the

heart-warming

Viennese

dance-tunes of

its trio are

reminiscent of

Haydn. Another

typical feature

is the way in

which an

insignificant

motif

obstinately

persists in

asserting itself

in the finale.

It

is, however,

within the

Quartet Op. 18

No.4 that we

find the oldest

stratum with

remains of the

Bonn period. Its

key of G minor

was equally

significant for

the Beethoven of

the early,

middle, and late

periods, but

here,

incidentally, it

has quite

different

emotional

overtones in the

first and last

movements. The

similarity (in

the first

movements) with

the Septet and

likewise with

the First

Symphony (in the

fugato

openings to the

second

movements)

points to

1798-1800 as the

period of

composition for

this work. It is

established that

the Quartet Op.

18 No. 3 was

composed first

and followed -

according to the

sketches found

by Gustav

Nottebohm - by

the Quartets

Nos. 1, 2, and

5.

As with the

fourth quartet,

we lack

corresponding

information

about the order

of composition

of the last

quartet. It is

undoubtedly the

most advanced;

it is in the

same key of B

flat major and

has the same

marking for the

first movement

as the Piano

Sonata Op. 22,

the two having

been partially

sketched out

together. There

is a hint of

later formal

developments in

the fact that

the first

movement clearly

yields pride of

place to the

scherzo, whose

exuberant

playfulness is

intended to

perplex both

players and

listeners with

its shifts of

emphasis

integrated in

masterly

fashion, and to

the unique

finale, whose

sub-title "La Malinconia”

(Melancholy) has

thrown up many

problems. The

impetuous

rhythmic drive,

which ultimately

dominates the

sombre and

restrained

introduction,

need not prevent

us from

regarding that

sub-title as

characterising

the whole

movement and not

merely the

beginning.

A critic of the

later Quartet

Op. 74, which he

bitterly

attacked, cast a

retrospective

eye over these

first six

quartets and

confirmed their

wealth

of imagination

and artistic

devices,

their

attractive

themes

appealing to

every shade of

feeling, and

the unity and

firmly

consistent

character of

every

movement,

worthy of

comparison

with the

masterpieces

of Haydn and

Mozart.

THE MIDDLE-PERIOD

QUARTETS

To the period

after the

completion of

the “Eroica"

Symphony, the

"Waldstein”

Sonata, Op.

53, and the

“Appassionata”

Sonata, Op. 57

belong the

three quartets

of Op. 59,

dedicated to

Count Rasoumovsky,

the Russian

ambassador to

the Austrian

court,

well-known in

contemporary

Vienna as a

considerable

art collector,

a very

competent

string-player,

and a keen

amateur of

music. While

the

introduction

of Russian

folk-tunes in

the first and

second

quartets may

be regarded as

no more than a

slight

courtesy

towards the

dedicatee, the

systematic

pursuit of

individual

aims in the

composition as

a whole

certainly

deserves

attention;

this is clear

in the first

public notice:

“Three new,

very long and

difficult

string

quartets by

Beethoven...

are also

attracting the

attention of

all

connoisseurs.

They are

profound in

thought and

splendidly

worked out,

but not

generally

comprehensible

- with the

possible

exception of

the third in C

major, which

must win over

every

knowledgeable

amateur of

music by its

individuality,

melody, and

harmonic power."

Through the

second movement

of the Quartet

in E minor, Op.

59 No. 2 there

blows a breath

somewhat

reminiscent of

the "Heiliger

Dankgesang eines

Genesenen an die

Gottheit” (Hymn

of gratitude

from a

convalescent to

the Divinity)

from the late A

minor Quartet,

Op. 132.

Considering the

profound and

heart-felt theme

of the

chorale-like

movement in the

E minor Quartet,

it hardly needs

the addition of

the special

marking: Si

tratta questo

pezzo con molto

di sentimento.

According to

Czerny it is

supposed to have

occurred to

Beethoven once

when he was

contemplating

the starry sky

and meditating

on the music of

the spheres.

Contemporary

opinion

immediately

accepted the

electrifying

virtuoso and yet

accessible

qualities of the

third quartet,

which correspond

to those of

piano sonatas

composed

contemporaneously

or shortly

before. As a

consequence of

the unmistakable

basic rhythmic

impulse, an Andante

con moto quasi

allegretto

has replaced the

normal Adagio

which might have

slowed the

impetus

excessively.

Similar

considerations

may have led to

the choice of a

fugal finale and

indeed to the

free extension

of what is a

closely

organised form.

The original and

special quality

in Beethoven is

increasingly

crystallised as

an

intensification

of expression.

His letter of

November 1, 1806

to the Scottish

amateur of

music, George

Thomson,

indicates the

possibilities

available to him

of applying his

art on different

levels. He says:

“I shall strive

to make the

compositions

easy and

agreeable as far

as I

can, and insofar

as I can

reconcile this

with that

loftiness and

originality of

style which,

according to

your own

testimony,

characterise my

works to their

advantage, and

from which I

shall never

depart."

However,

Beethoven’s main

stream of

composition

followed other

laws. This is

how the reporter

of the Leipzig

“Allgemeine

Musikalische

Zeitung"

interpreted the

E flat Quartet,

Op. 74 in his

own fashion:

“The composer

has here devoted

himself

uncompromisingly

to the most

remarkable and

strange

conceptions of

his original

imagination, has

fantastically

woven together

the most

disparate

elements, and

has treated

almost all of

them witn such

profound and

difficult art

that even the

lighter and more

pleasing details

have simply

foundered in the

ambient gloom."

He concludes

severely by

saying that he

could not wish

instrumental

music to lose

its way in this

fashion; that

the purpose of

the string

quartet as a

genre could

surely not be to

commemorate the

dead or to

describe the

feelings of

those in

despair, but

rather to raise

the listeners

spirits by the

gentle and

beneficent play

of the

imagination. A

confusion of

dissonances

towards the end

of the Adagio,

a virtually free

tantasia in the

Allegro

of the first

movement,

war-like dances,

as it were, of a

savage people in

the third

movement, and a

finale

consisting of

variations which

are profound and

original rather

than pleasing -

all these

elements were

here marshalled.

The sub-title

“Quartetto

serioso" is to

be found in the

manuscript of

the F minor

Quartet, Op. 95.

An

attempt has been

made to relate

the "serioso"

to Beethoven’s

offer of

marriage to

Therese

Malfatti, which

was refused.

Hugo Riemann

began a

discussion of

this work by

saying: "The

first movement

is perhaps the

most brusque

that Beethoven

has ever

written." He

here refers to a

certain motif

which occurs

about 50 times

in the mere 151

bars comprising

the first

movement.

Beethoven was

perfectly aware

ofthe nature of

the work. In

mid-October he

explained in a

letter to George

Smart in London

that the quartet

was written only

for a small

group of

connoisseurs and

was never

intended to be

played in

public. Written

as early as

1810, it was

published only

in December

1816. The

dedicatee,

Beethoven’s

friend Nikolaus

von Zsmeskall

was a

professional - a

very competent

cellist who

himself left no

fewer than 14

original

quartets.

THE LATE

QUARTETS

The last and

ripest phase, in

which the

quartet form has

its strongest

individual

significance and

in which

Beethoven’s

language,

refined by

experience, is

at its most

spiritual,

begins with the

Quartet in E

flat, Op. 127.

Here, in the

first movement,

the cantabile

style, indeed "infinite

melody" in the

Wagnerian sense,

predominates.

The almost

religious

meditation of

this movement is

intensified in

the subsequent

movement (Adagio

ma non troppo

e molto

cantabile)

to a

transcendental

and fervent

transfiguration.

In

the

bridge-passage

to the theme and

variations we

find a structure

absolutely

peculiar to

Beethoven. The

scherzo, one of

the greatest,

and a work of

genius, takes

its place beside

the incomparable

scherzo of the

Ninth Symphony,

work on the

ending of which

interrupted work

on the quartet

for months at a

time. The finale

(in the form of

a rondo with

free episodes)

gives an overall

impression of

serenity, but

ends misted in

obscurity - in a

mood removed, as

it were, from

earthly things.

The Mainz

publisher

Schott, who

reckoned this

work to be the

summit of

instrumental

music, could

still not

refrain from

pointing out

certain

difficulties. In

a letter of the

period Beethoven

complained of

the scandal of

general public

taste being far

inferior in the

artistic world

to that in

private circles.

It

is also worth

noting that

success came

only with the

second

performance, in

which Joseph Böhm

replaced lgnaz

Schuppanzigh as

leader.

The last four

quartets all

belong to the

years 1825-26,

though in fact

composed in a

different order

from that

indicated by the

opus numbers.

The A

minor Quartet,

Op. 132, dates

from February to

the end of July

1825 and the B

flat Quartet,

Op. 130, with

the "Grosse

Fuge"

(subsequently

issued

independently as

Op. 133) as

finale, from

July to

November. In

the first six

months of 1826

there followed

the C sharp

minor Quartet,

Op. 131, and

from July to

October the F

major Quartet,

Op. 135.

Finally, the

period from

September to the

beginning of

November

produced the

definitive

finale of the B

flat Quartet,

Op. 130, which

at the same time

represents

Beethoven’s last

complete major

composition.

(For the

listener`s

convenience,

both finales are

presented in

these recordings

on Side 16, with

the “Grosse

Fuge" taking

pride of place.)

Ii

is not only in

his late works

that

Beethoven, despite

the narrow

confines in

which he moved,

burst the bounds

of traditional

dimensions not

only by

increasing the

number of

movements but by

electing to

compose such a

colossal finale

as the "Grosse

Fuge" (though

later yielding

to the advice of

friends). Even

the "Waldstein"

Sonata started

life with an

extended middle

movement which

was replaced by

a Short "Introduzione"

to the finale

and published

separately as

the "Andante

favori."

According to a

report by his

friend Karl

Holz, Beethoven

is supposed to

have wept tears

of sorrow as he

composed the

Cavatina: "He

confessed to me

that his own

music had never

yet produced

such an

impression on

him, and that

even to

re-experience it

cost him fresh

tears."

We can,

incidentally,

judge of the

labour which

Beethoven

undertook by the

sketches which,

in the case of

the C sharp

minor Quartet

alone, occupy

three times the

volume of the

fair copy. In

spite of

everything,

however, he was

not

uhremittingly in

deadly earnest,

either in music

or in words;

lack of humour

is rather a

characteristic

of his

contemporaries,

who took the

facetious remark

on the

proof-copy: "Filched

and put together

from various

sources, here

and there," at

its face-value

and thereby

occasioned a

corresponding

explanatory

letter.

The inscription

on the third

movement of the

Quartet in A

minor, Op. 132-

“Heiliger

Dankgesang eines

Genesenen an die

Gottheit in der

lydischen

Tonart" (Hymn of

gratitude from a

convalescent to

the Divinity in

the Lydian mode)

refers to a

serious illness

which caused an

interruption of

work in the

spring of 1825.

At the rehearsal

on September 7,

1825, the

solemn, and

pious mood of

this movement is

supposed so to

have affected

Johann

Woltmayer, the

rich cloth

merchant and

patron of the

arts, that he

wept like a

child.

Work on the

Quartet in F,

Op. 135, lasted

until late

autumn of 1826,

since Beethoven

had undertaken

the fateful

journey to his

brother’s

property near

Gneixendorf,

from which he

was to return to

Vienna with his

mortal illness.

The most

impressive

contemporary

document

concerning

Beethoven’s late

style of quartet-writing

is an unusually

extensive notice

of the C sharp

minor Quartet,

Op. 131, which

Friedrich

Hochlitz

published in the

Leipzig "Allgemeine

Musikalische

Zeitung" on July

23, 1828, more

than a year

after

Beethoven’s

death. Rochlitz

went so far as

to doubt, though

with

unmistakably

cautious

reserve, the

capacity of the

aging master to

compose at all

since, almost

completely

devoid of

hearing, he

could at the end

only have lived

his own inner

life. He found

fault chiefly

with

introspective,

disconnected

combinations,

with themes too

overlaid with

instruments

weaving

variations, or

too violently

alternating

figurations

making it almost

impossible to

distinguish the

melody. The

themes

themselves he

found frequently

quite strange,

the modulations

acute to a

bizarre degree,

and the time

signatures

changing too

abruptly. On the

other hand, he

conceded that

these works

demanded

intelligent and

repeated

hearings and

above all an

appropriate

interpretation.

However,

Beethoven’s

greatness was

unassailable as

far as he was

concerned; nor

was he certain

whether this

last period

should not after

all be regarded

as a

well-considered

stylistic

development.

“Beethoven did

not

compromise...

least of all did

he compromise in

his last

works... He has

been called the

inventor of his

time musically

speaking, and

that he is

indeed. When

scarcely more

than a youth he

was already

producing works

which were

original, which

belonged to him

alone, which

could only have

come from him.”

It

almost seems

as if

Rochlitz, who

anyway held

Beethoven in

high esteem,

suspected that

the composer

might

ultimately be

proved to be

in the right

despite such

criticism; at

any rate he

considered it

appropriate to

quote

Lichtenberg’s

well-known

saying,

obviously in

Beethoven’s

favour: "If

a head and a

book are

knocked

together and

there is a

hollow sound,

must it always

come from the

book?"

HANS

SCHMIDT

Beethoven-Archiv,

Bonn

Translated

by Francis

Català

NOTE FOR

THE

SCORE-READERS

The basic

score for the

Quartetto Italiano`s

performances

of the late

string

quartets was

the Universal

Edition (based

on the first

editions of

the original

versions).

However, in

the violin

parts of the

substitute

finale of Op.

130 (Side 16),

at bars 98 and

99 (the poco

ritardando

after the

double-bar of

the

exposition),

the F sharp of

the Peters

edition has

been preferred

to the F

natural of

Universal.

QUARTETTO ITALIANO

The Quartetto

Italiano is

deservedly one

of the most

renowned

quartets of

our time. It

was as long

ago as 1945,

soon after

completing

their studies,

that Paolo

Borciani,

Elisa

Pegreffi,

Piero Farulli,

and Franco

Rossi,

resisting the

tempting

promise of

individual

careers as

soloists,

decided to

pool their

youthful

enthusiasm and

musical talent

and devote

themselves to

the difficult

but satisfying

art of playing

chamber music

really well.

By 1947 the

group had

established a

firm

reputation in

the musical

press and

begun giving

concerts

outside Italy.

In1951

they visited

the United

States for the

first time,

and it was

soon apparent

that their

devotion to

their music

and the

impeccable

standards of

performance

they had set

for themselves

were earning

them fame as

well as

satisfaction.

Over the years

since 1945

they have

remained

together, a

rare example

of teamwork in

music.

To list the

group`s

wide-ranging

activities in

more than 30

years is

pointless:

they have done

everything one

might expect

of one of the

world’s finest

quartets. They

have given

hundreds of

concerts all

over Europe

and in the

United States;

they are

regular

participants

in the

chamber-music

concours of

many

countries; and

they have

played and are

in constant

demand at the

world`s great

music

festivals.

Outside the

concert

circuit the

members of the

quartet teach

chamber music

at both the

Royal Academy

of Music in

Stockholm and

the

Conservatoire

in Vienna.

In

addition to

the many words

of praise

bestowed on

them - after

their first

concert in New

York, Virgil

Thomson, the

distinguished

critic of the

"New

York Herald

Tribune,"

called them

“the finest

quartet,

unquestionably,

that our

century has

known” - they

have been

publicly

honoured by

the President

of Italy as a

more tangible

recognition of

their

outstanding

artistic

services over

the years to

Italy in

particular and

the world of

music in

general.

|

|

|