|

|

Philips

- 2 LPs - 6770 042

|

|

QUARTETTO

ITALIANO

- Paolo Borciani,

Elisa Pegreffi, violino

- Piero Farulli, viola

- Franco Rossi, violoncello

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione |

|

La

Tour-de-Peilz (Svizzera)

-

20-30 luglio 1971

(K. 499 & 575)

-

14-17 gennaio 1972

(K. 589 & 590)

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Vittorio Negri

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Philips | 6770 042 | 2 LPs |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Philips | 416 419-2 | 8 CDs (7°,

1-4, 5-8; 8°, 1-4, 5-8) | (c)

1990 | ADD

|

|

|

Note |

|

Ripubblicazioni

in cofanetto

degli ultimi

quattro

quartetti di

Mozart tra cui i

tre cosiddetti

"Prussiani".

|

|

|

|

|

MOZART’S

LAST FOUR

STRING

QUARTETS

Although in

early

literature

Mozart’s

contretemps

with

Archbishop

Colloredo of

Salzburg is

readily seen

as proof that

he was the

first

independent

artist in the

history of

music and a

man who

proudly turned

his back on

court service,

the truth is

that

throughout his

life he strove

to obtain an

appointment at

a prince’s

court. He made

his last

attempt in

this direction

in 1789, when

on April 8, at

the invitation

of and in

company with

Prince Karl

Lichnowsky, he

travelled to

Berlin where

the

music~loving

King Frederick

William II

of Prussia was

supposed to be

expecting the

musician from

Vienna. But

the

monarch

was by no

means in a

hurry and at

first referred

the new

arrival to

Jean Pierre

Duport, his

famous cellist

and director

of chamber

music. It

was only at

the end of

April, after

Mozart

undertook an

excursion to

Leipzig, again

at the

suggestion of

Lichnowsky,

that he

finally played

for the king.

However,

Mozart’s hopes

for an

appointment in

Berlin were

not to be

fulfilled. In

a letter to

his wife

Constanze of

May 23, he

wrote;

"...when I

return you

will have to

be looking

forward to me

rather than to

money."

Nevertheless,

the king had

provided him

with two

musical

commissions.

Besides six

easy piano

sonatas for

Princess

Friederike, he

requested six

string

quartets - he

prided himself

on his skill

as a cellist.

Even though at

that time

Mozart was

living in very

reduced

circumstances,

he only

completed a

small part of

each

commission. Of

the six

sonatas he

composed only

one, that in

D, K. 576,

which is

anything but

“easy,” and

which probably

never reached

its addressee.

Half of the

quartet

commission was

honoured,

though only

the first

quartet, K.

575 in D,

composed in

Vienna in June

1789 and

specifically

described in

Mozart’s work

catalogue as

having been

written “for

His Majesty

the King of

Prussia,”

actually

reached Berlin

and is

believed to

have brought

Mozart a

reward of 100

Friedrichs d`Or

in a gold

snuff-box. The

other two

quartets,

Mozart’s last

works in the

genre, were

published

without any

dedication to

the king

shortly after

Mozart’s death

in a very

careless and

seemingly

hastily

prepared

edition by the

Viennese

publisher

Artaria. This

edition also

included the

first quartet.

Artaria seems

to have

obtained the

three works

very cheaply,

for we know

that in one of

his begging

letters to his

fellow-Mason

Puchberg

Mozart wrote

in May 1790: “I

am now obliged

to give away

my quartets on

which I worked

so assiduously

for a trifling

sum simply in

order to get

cash in hand

for my present

circumstances.”

It is not

known why

Artaria waited

until after

Mozart’s death

before

publishing.

Common to all

three of the

so-called

“Prussian”

Quartets is

the prominent

role given to

the cello

part, which is

often written

in its higher

register and

hence very

tellingly. In

including this

characteristic

feature,

Mozart was

bearing in

mind the

ability of the

king and above

all of his

famous teacher

Duport. It

brings into

play a

slightly

concertante

style which

distinguishes

these last

quartets from

the six more

tightly-knit

quartets of

1782-85 that

Mozart

dedicated to

Haydn. Their

lucid yet

enigmatic

cheerfulness

recalls the

almost

contemporaneous

“Cos'

fan tutte.”

Finally the

three works

share a

proclivity

towards

"singing,"

melodiously

written

themes.

This is

apparent right

from the start

of the Quartet

in D, K. 575:

the song-like

main theme of

the Allegertto

may have been

a product of

Mozart’s stay

in Milan

during 1773,

but the

artistry of

his later

reworking,

using

suspensions

and rapid

quavers,

reveals the

compositional

mastery of

Mozart’s final

years. The

same is also

true of the

development

section with

its

condensation

of the

exposition's

wealth of

material into

constantly

varying

combinations.

Characteristically,

the secondary

theme of the

exposition is

given out by

the cello. The

melody of the

A major Andante

is not

difficult to

recognise as a

variant of the

song “Das

Veilchen,"

dating from

1785. This

same movement,

with its

inward-looking

tunefulness,

is a

triumphant

example of the

mature

Mozart’s

technique of

variation,

which in the

central

section

evolves

development-like

structures

without

thereby

affecting the

music’s

lyrically

expressive

character. The

D major minuet

has virtually

nothing in

common with

the

traditional

dance

movement;

powerful sforzati

give it a

highly

energetic

stamp. The

trio is the

preserve of

the royal

cellist, who

is here given

a broad-ranging

melody to play

which seems to

anticipate

Schubert and

is ultimately

taken over by

the violin.

Extreme

independence

of thought is

shown in the

finale, a kind

of rondo in

which at each

reappearance

the memorable

theme - once

again of an

exceedingly

song-like

nature - is

shownin a

fresh light,

embellished,

and reworked

in a different

counterpoint.

Although

avoiding

strict

polyphonic

writing,

Mozart makes

use of the

technique of

thematic

inversion. The

consummate

writing of

this movement

is highly

characteristic

of Mozart’s

late style:

the density of

the

construction

is so

completely

integrated

that the

listener is

scarcely aware

of the

complexities.

The Quartet in

B flat, K.

589, dates

from May 1790.

The lengthy

time he took

to write the

six “Haydn”

Quartets and

remarks he

made in

letters about

the

composition of

quartets are

not the only

evidence we

have that

Mozart, for

all his

facility and

speed in other

kinds of

composition,

found it hard

work when it

came to

quartet

writing. In

the case of

the B flat

Quartet, there

even exists a

fragment of a

finale (K.

589a) which

Mozart then

rejected. The

first

movement, with

its violent

dynamic

contrasts,

culminates in

a very

imposing

development

section which

is worked out

in an

exceptionally

concentrated

way. In the Larghetto

in E flat, the

cello again

has the main

say,

alternating

with the first

violin in its

thematic

presentation,

whose cantabile

melodic flow

is enlivened

by dotted

rhythms. In

the reprise,

which is still

further

animated by

nimble

demisemiquavers,

the duet

between the

cello and the

violin returns

in the reverse

sequence. The

minuet is of

unusual

dimensions:

though

appearing to

start rather

conventionally,

it proceeds to

a broadly

designed trio

whose agitated

opening on the

cello,

penetrating

semitone

steps, and

abrupt change

of key, open

up extremely

original

worlds of

sound and

expression.

The theme of

the finale,

too, written

in a swift 6/8

metre, makes

out to be

innocuous and

reminiscent of

Haydn, but

quickly

becomes

involved in

contrapuntal

complexities

which

ultimately

characterise

the entire

movement,

above all the

development

section, again

an extremely

masterly one.

The theme is

brilliantly

set off

against its

own inversion,

while

fragments of

it appear

interspersed

as subsidiary

and answering

contrapuntal

voices.

Mozart’s

“assiduous

work” is more

noticeable

here than in

the finale of

the D major

Quartet. We

know that the

work was

played in

Mozart’s home

shortly after

he had

completed it.

Mozart’s last

string

quartet, the F

major, K. 590,

dates from

June 1790. In

working on it

he seems more

and more to

have forgotten

about the king

who had

commissioned

it, as the

cello is now

given a

soloistic role

only in the

first two

movements. The

first movement

is an Allegro

rnoderato

which evolves

from a

rising-triad

theme whose

continuation

once more

produces a

dialogue

between cello

and first

violin. And in

the subsidiary

idea developed

from the

opening theme

the cello is

still given

pride of

place. The

development

section again

leads into

stretches of

polyphony and

the

recapitulation

emerges as a

considerably

modified

version of the

exposition.

The Allegretto

in C derives

its special

feeling from

the lively

counterpoints

with which all

four

instruments

decorate the

melancholy

striding

theme.

Einstein

rightly called

this strangely

twilit

movement “one

of the most

sensitive

movements in

the whole

literature of

chamber music."

Unusually

luxuriant

harmonic

modulations

contribute to

the impression

of a music

that eludes

definition in

emotional

terms. The

minuet and

finale appear

to salute

Haydn. The

extremely

brilliant

sonata-form

finale can be

classed among

those quartet

movements of

Mozart’s in

which

compositional

procedures of

the utmost

complexity are

concealed

beneath what

seems a smooth

surface: the

“assiduous

work” which

must have gone

into the

important

development

section in

particular

remains

largely

inconspicuous,

even though it

calls upon

some of the

heaviest of

contrapuntal

artillery in

the shape of

inversions and

contrary

motion.

Whereas the

three

“Prussian”

Quartets were

Mozart’s last

utterance as a

quartet

composer, the

D major

Quartet, K.

499 of four

years earlier

is in many

respects still

a puzzling

special case.

The score

announces its

date of

composition as

August 19,

1786, and is

most unusual

for that

period in

being an

isolated work.

There is a

strong

suggestion

that Mozart

wrote the work

for the

Viennese

publisher

Franz Anton

Hoffmeister

- who did

indeed publish

it - as a

means of

paying off

some of his

debts to him.

We possess a

begging letter

from Mozart to

Hoffmeister,

dated November

20, 1785, in

which the

composer begs

the publisher

to “just

assist me

meanwhile with

some money as

at the moment

I am direly in

need of it.”

If

in many

respects the

“Prussian”

Quartets are

close to "Cosě

fan

tutte,"

the “Hoffmeister”

Quartet calls

to mind

“Figaro.” The

unison theme

of the first

movement is

once more

reminiscent of

Haydn, as too

is the fact

that the

movement shows

signs of being

monothematic,

namely that

unlike the

finale it

lacks a

contrasting

subsidiary

idea. Once

again Mozart

typically

introduces

contrapuntal

subtleties

that the

listener will

scarcely

notice as

such, as for

example the

canonic

interplay

between the

first violin

and the cello

and the tricks

of thematic

inversion

which play

their part in

the

development

section. In

this work the

minuet is the

second

movement. The

dance-like

outer sections

contrast with

the trio which

moves to the

minor, and

shows off

brilliant

effects of

fragmentation;

here, the

subsequent

theme of the

finale is

anticipated in

a minor-key

variant. The

expressively

singing G

major Adagio,

one of

Mozart’s most

impressive

slow

movements, is

entirely

bathed in

euphony of

lyrical

radiance. The

mainspring of

the

sonata-form

finale is the

contrast

between the

whirling

triplet motion

of the opening

theme and the

march-like

strides of the

secondary

theme, forming

a rhythmic

counterpoint

which is

audibly

carried to

extremes,

notably in the

brief

development

section.

Together with

the six

quartets

dedicated to

Haydn, written

between 1782

and 1785,

Mozart’s last

four string

quartets

represent a

peak of the

art of quartet

composition

beyond which

it was not

possible to

go. For late

Beethoven and

late Schubert

went along

different

routes.

By

Alfred

Beaujean

|

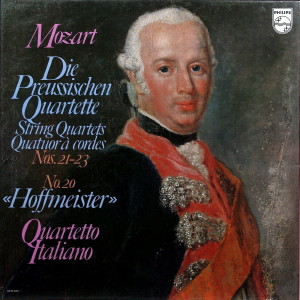

| Illustration:

Anonymus "Friedrich Wilhelm II.

von Preußen" (Nationalgalerie,

Berlin) |

|