|

|

Philips

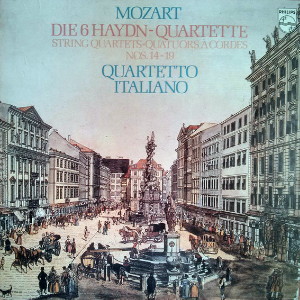

- 3 LPs - 6998 014

|

|

| Philips

- 3 LPs - 6770 052 |

|

QUARTETTO

ITALIANO

- Paolo Borciani,

Elisa Pegreffi, violino

- Piero Farulli, viola

- Franco Rossi, violoncello

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione |

|

Théâtre

Vevey, Vevey (Svizzera)

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Vittorio Negri

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Philips | 6998 014 | 3

LPs

Philips

| 6770 052 | 3 LPs

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Philips | 416 419-2 | 8 CDs (4°,

1-4, 5-8) | (c) 1990 | ADD | (KV

387 & KV 421)

Philips | 422

832-2 | 1 CD - 55' 37" | (c)

1989 | ADD | (KV

428 & KV 458)

Philips | 426

099-2 | 1 CD - 65' 52" | (c)

1990 | ADD | (KV 464 &

465)

|

|

|

Note |

|

Pubblicazioni

in cofanetto dei

sei quartetti di

Mozart dedicati

a Franz Joseph

Haydn.

|

|

|

|

|

THE

SIX SONS OF

MOZART

"To

my dear friend

Haydn: A

father who had

decided to

send his sons

out into the

wide world

thought in was

his

responsability

to entrust

them to the

care and

guidance of

someone who

was very

famous at that

time and who,

furthermore,

happeaned to

be his best

friend.

Similarly I

send my six

sons to you,

my very

distinguished

and very dear

friend. They

are, in fact,

the fruit of

long and

laborious

toll; but many

friends have

encouraged in

me the hope

that this teil

will be

rewarded in

some measure

and I am

gratified by

the thought

that these

children might

be a comfort

to me some

day. During

your last

visit to the

capital, my

dear friend,

you personally

expressed to

me your

approval of

these works.

Your good

opinion

prompts me to

offer them to

you and to

hope that you

will not find

them

altogether

unwortly of

your

approbation.

Therefore

please receive

them kindly

and be a

father, guide,

and friend to

them. As from

now I give up

to you all my

rughts over

them, I beg

you, however,

to forgive

those faults

which may have

escaped a

father's

prejudiced eye

and to

maintain in

spite of them

your generous

friendship to

someone who

appreciates it

so

much... W. A.

Mozart."

It

was in these

terms, in a

letter dated

"Vienna,

September 1,

1785," that

Mozart

dedicated to

Joseph Haydn

the six string

quartets on

these records.

The letter

immediately

established

two important

points -

first, the

works were not

thrown off to

order, as was

much of

Mozart's

music; second,

he venerated

Haydn enough

to be

considerably influended

by his work.

The

veneration in

this context

is quite

understandable.

At the time

the letter was

written more

than 40 string

quartets had

been composed

by Haydn and

they

represented

most of the

significant

growth of the

form from

simple

divertimenti

for a merely

fortuitous

combination of

instruments

wothout a

continuo to

the highly

demanding

medium of

musical

expression

which not much

later was to

be the channel

of Beethoven's

inspiration.

Alongside

this

development of

the string

quartet as a

form Mozart

himself

developed. In

his 13

quartets

before the

"Haydn" set we

can see the

early

influence of

the Italian

style soon

being

superseded by

the influence

of Haydn's

experiments;

we can see the

emancipation

of the viola

and cello,

which become

increasingly

independent

voices instead

of stiff and

servile

accompanying

instruments.

But before

Mozart's

quartets

became fully

mature he himself

had to win

artistic

emancipation.

The last

quartet before

the six which

concrn us was

written in

1773, when

Mozart was in

the service

of the

tyrannical

Archbishop of

Salzburg. But

by the time he

began the

first "Haydn"

quartet in

1782 he had

broken free of

the court's

shackles,

married the

woman he loved

(against his

father's

wishes), and

set up home in

Vienna, facing

the world with

little

material

support but

with a brave

new spirit of

independence

which helped

to make the

boy a man and

the precocious

composer a

master of his

art.

Strangely,

and perhaps

significantly,

Mozart's

inactivity in

the field of

the string

quartet

between 1773

amd 1782

matches a

similar pause

in Haydn's

quartet output

which stepped

in 1772 and

began again in

1781. In that

year Haydn

published the

famous

"Russian"

quartets, a

set of six

which he

announced as

having been

written "in am

entirely new

and special

manner." The

announcement

was more than

a mere

adversting

gimmick, for

the works

displayed a

much greater

degree of

artistic unity

than had been

apparent

before,

particularly

in the close

relationship

of their

thematic

material.

There is no doubt

that Mozart

was

considerably

impressed and

influenced

by this new

step forward

in Haydn's

week. And it

was probably

the decisive

factor in

spurring him

on to take up

the form again

in 1782 with

the G major

quartet, K.

387. It is in

this work that

we first meed

a new Mozart -

a Mozart who

looks forward

to Beethoven

rather than

backward to

the Baroque.

We see him

striving for

and achieving

the unity that

Haydn sought

in the

"Russian"

quartets, but

in a

completely

individual

way. As the

set tales

shape we often

find movements

that are

Haydnesque,

but within

their context

they could

have been

written only

by Mozart.

FLOWERING

OF A

FRIENDSHIP

Exactly

when Mozart

conceived the

idea of the

dedication to

Haydn is not

clear but it

seems likely

that it was

not until the

personal

acquaintance

of the two

composers

became a close

friendship in

1784 when

Haydn, then

Prince

Nicholas

Esterházy's

musical

director, paid

an extended visit

to

Vienna. On

several

occasions

Mozart was

invited to

play at the

Esterházy

musical

evenings and

soon both

Haydn and he

were taking

delight in

playing

chamber music

privately

together with

mutual

friends. By

the time this

personal

friendship had

fully flowered

three of the

quartets in

the "Haydn"

set had been

written. From

the musical

point of view,

however, the

matter is of

incidental

interest. What

is important

is that the

set as a whole

displays

a wonderful

integration of

style,

technique, and

meed, and when

it was finally

presented to

Haydn in 1785

he at once

recognised the

true genius

behind it.

This was to

his credit for

hitherto he

could hot have

bad much

opportunity to

assess the

real stature

of the young

composer -

and, in fact,

these quartets

added a

totally new

dimension to

it. It was a

good example

of the maxim

that in

sometimes

takes genius

to recognise

genius. After

a performance

of three of

the works at

Mozart's home

Haydn drew

aside Leopold,

the composer's

father who was

on a visit

from Salzburg

at the time,

and told him

confidentially:

"I declare to

you before God

as an honest

man that your

son is the

greatest

composer I

know either

personally or

by hearsay; he

has taste and,

moreover,

complete

mastery of the

art of

composition."

The

quartets not

only impressed

Haydn

profoundly as

a listener and

performer:

henceforward

they were to

excet a

noticeable

influence on

his own work -

as they were

also to

influence

Beethoven when

he, in turn,

came to carry

the quartet to

its spiritual

zenith.

FORM,

STYLE, AND

PERFORMANCE

These

are not the

last string

quartets that

Mozart wrote

but they are

certainly the

greatest. They

are the first

of what are

sometimes

known as his

"ten great"

quartets, the

others being

the D major

(K. 499) of

1786 and the

three written

in 1789-90 for

the king of

Prussia. While

the last three

are

constructed

with masterly

skill we find

Mozart writing

again for a

particular

purpose - this

time so show

off His

Majesty's

proficiency as

a cellist. The

"Haydn"

quartets have

no such

limitations on

style and give

Mozart the

chance to

express

himself freely

and naturally.

The

outstanding

characteristics

of all six are

their

brilliant

construction

and the

contrapuntal

treatment of

the material.

The works

abound in

fugal

incidents and

the use of

canons.

sometimes in

what appear to

be impossible

circumstances.

Canons by

their very

mature are

limited to

sequances

which happen

to match

harmonically

and

contrapuntally.

Obviously

complicated

melodies are

less likely to

be suitable

for canons

than short

simple

thematic

statements.

This may seem

irrilevant,

but the

abundance of

canons in

these quartets

points to the

fact that,

contrary to

popular

belief, Mozart

was a thematic

rather than a

melodic

composer. In

isolation his

themes in

these quartets

follow

relatively

simple

patterns but

it is this

very fact that

enables him to

build with

them complex

structures

which

nevertheless

are so

artistically

integrated

that they

flatter the

car before the

intellet; one

need not be

aware of the

technicalities

to enjoy the

effect.

In

these quartets

we also find

Mozart

adapting form

to his own

purpose in a

subele way

that opened up

great

possibilities

for the

future. By

combining

characteristics

of rondo and

sonata form in

some

movements, for

instance, he

develops his

material as it

returns and so

can dispense

with the

development

section of the

basic

sonata-form

structure. His

codas, when

they appear at

all, make a

fascinating

study

particularly

in the last

two quartets

of the st. The

intimacy of

chamber music

made the

theatrical

introduction

(designed to

warm audiences

that a work

was starting)

and the

theatrical

coda (which

told them it

was ending)

unnecessary

encumbrances.

Save for the

mysterious

opening of K.

465, Mozart

dispenses with

the

introduction

in these

works; but in

many instances

he retains the

coda and puts

it no another

use in

movements of

sonata form.

Here we find

melodic

effshoots of

main thematic

material

finding a

place in

codettas and

codas in a way

which

anticipates

the much

bolder

developments

by Beethoven

in this field.

Mozart's

minuets, while

retaining

accepted form,

are no longer

purely dances

nor are they

the

light-hearted

interludes

that Haydn

developed and

which in

Beethoven's

hands became

scherzos. In

these quartets

they are

integral parts

strcuturally

of the works

in which they

appear. In

some cases

their function

is to provide

emotional

contrast or

even relief,

but they are

equally often

moulds into

which Mozart

cam pour

surprisingly

intenue

feeling - in

the minuet of

K. 421 for

instance - and

where there is

a marked

overall

pattern the

minuet

material plays

its full part.

In

this respect

the care that

the Quartetto

Italiano have

taken in these

recordings in

going back

wherever

possible to

the original

tempo

indications is

importat. The

tendency

of the time

the quartets

were written

was towards an

increase in

pace in the

minuet,

particularly

in the works

of Haydn.

There is

reason to

believe,

however, that

Mozart was

concerned

about this

tendency and

that this was

reflected in

his original

tempo

indications.

Believing that

clarity of

detail and

care in the

expression of

mood and

character are

of first

importance in

these works,

the Quartetto

Italiano have

adhered, for

instance, to

the

"allegretto"

markings of

the first

edition rather

than the

"allegro" of

later editions

in general

use. It was

not a lightly

taken step.

All the

bowings,

tempi, and

dynamic

indications

used in these

performances

have, in fact,

been decided

on only after

the most

careful

research by

the members of

the quartet

themeselves

based on the

autograph and

fist editions

and other

important

contemporary

documents.

These have

been studied

carefully and

compared with

later sources,

particularly

the Einstein

and Bärenreiter

editions. The

result on

these records

is not so much

a performance

as a dedicated

reappraisal of

these six

masterpieces.

--------------------

QUARTET

IN G, K. 387

Completed

on New Year's

Eve 1783, this

work

immediately

marks the new

maturity of

style and

mastery of

construction

which

characterises

the set as a

wholle.

Throughout one

senses rather

than recognises

the

significance

of every note

on every

instrument. It

has the kind

of unity one

meets in the

later

Beethoven

piano sonatas

where all the

material has a

general

"family"

resemblance,

and it

has the same

strength of

character.

The

main theme of

the first

movement (in

sonata form)

is

announced

immediately by

the first

violin and

provides the

basis for the

work as a

whole. In

fact, the

theme iteself

is a melodic

development of

its first two

phrases. The

important

elements are

the interval

of a fourth

which rises to

the tonic at

the start of

the theme

(this

dominates the

work, often

being filled

in with notes

which either

rise or fall

in scale

sequances) and

the drooping

chromatic

shape of the

second phrase.

The second

subject,

distinguished

by an

important

oscillating

phrase,

appears first

at

the second

violin and,

although

structurally

related to the

first theme,

is very

different in

character. The

minuet and

trio borrow

these

features; even

the dense

alternation of

piano

and forte,

lending a

feeling of

cross-rhythm

to the main

theme, is

derived from

the previous

movement.

In the restful

Andate

(in C) which

follows there

is an almost

continuous

development of

the main theme

until a sparse

functional

modulation

takes us back

from the

dominant to a

cleverly

varied

recapitulation.

The finale is

a superbly

constructed

fugal movement

in sonata form

later to have

its symphonic

counterpart in

the "Jupiter"

Symphony.

The ubiquitous

fourth is at

the heart of

the initial

subject and

after the taut

complexity of

its fugal

treatment the

tuneful almost

jocular second

subject comes

as a surprise,

although it

has the

"family" resemblance.

There is a

pseudo-development

in which

a

chromatic

sequence

shrough the

fourth passes

from

one instrument

to another and

leads us

surreptitiously

into the

recapitulation.

The work ends

with a calm

simple

restatement of

the initial

fugue subject.

QUARTET

IN D MINOR, K.

421

Structural

unity is the

hallmark of K.

387 and

emotional

unity that of

K. 421, which

was written by

Mozart in June

1783 - part ot

it while his

wife was

giving birth

to their first

child. It is

the only

quartet of the

set in a minor

key and an

inescapable

air of

melancholy

pervades the

whole work. While

we can never

trust Mozart's

music as a

reflection of

his

circumstances

or personal

character, one

cannot help

feeling that

here he has

exposed a

little more of

his soul than

he normally

allows us to

se. All this

is not to say

that emotion

is a

substitute for

the craftsmanship

of K. 387; on

the contrary

the work is

constructed

with masterly

precision and

there is the

same sense

of basic

unity.

The

main theme of

the passionate

first movement

again reveals

some unifying

elements - a

sobbing dotted

quaver and

reiterated

notes in

clutches of

three in the

accompaniment

(this, is the

4/4 time of

the movement,

adds to the

air of

agitation).

Reiterated

notes also

accompany the

second theme

in F major. In

the

development

which opens

with a bold

modulation to

E flat, a

prominent part

is played by a

sextuplet wich

makes its

first

appearance in

the codetta.

While the

fourth was

predominant in

K. 387, the third

is the

important

interval in K.

421,

particularly

in the Andante

(in F). The

tender,

reflective

theme, in

which the

rests play an

almost melodic

part, centres

round a third

in its first

phrase.

Recurring

elements which

soon emerge

are the

reiterated

notes and the

sextuplet,

which now fits

normally into

the 6/8

rhythm.

Instead of

providing

relief the

minuet takes

us back in

key, mood, and

structure to

the restless

main theme of

the first

movement. With

a change to D

major

and a

pizzicato

accompaniment,

the first

violin makes a

determined

effort to be

cheerful in

the trio but

never quite

shakes off the

air of melancholy.

The final

movement is a

set if

variations on

a Siciliano

theme. As 6/8

rhythm, a

minor key, and

the dotted

quaver are all

characteristic

features of

the Siciliano,

the theme fits

the character

and structure

of the work

perfectly.

Again its

basis rests on

thirds and

reiterated

notes. The

last variation

moves to D

major and is

more restful

but the theme

returns to end

the work with

all the

intensity with

which it began.

QUARTET

IN E FLAT, K.

428

This

quartet

composed in

1783 is full

of sudden and

surprising

flashes of

inspiration,

and we get one

almost as soon

as the work

has begun. The

cromatic main

theme of the

first movement

is immediately

stated in bold

unison, giving

a feeling of

tonal

ambiguity after

an initial

united

emphasis on

the tonic E

flat. But when

the theme

reappears a

few bars

later it is

suddenly

richly

harmonised

with bold use

of a

diminished

seventh. A

long trill on

the first

violin

announces the

arrival of the

second theme

which is more

comfortingly

melodic. The

development is

dominated by a

soaring

passage of

triplets and

is followed by

one of

Mozart's

cleverly

reworked

recapitulations,

the highlights

being a

delightful

little canon

of one of the

exposition's

linking

phrases and a

new, smoothly

flowing

accompaniment

to the main

theme.

In the richly

chromatic

second

movement (Andante

con moto),

the tension of

the masterly

harmony

contrasts

perfectly with

the smooth legato

phrasing of

the theme and

provides an

exquisite

bittersweet

quality. The

minuet (in E

flat) is

delightfully

fresh and

stimulating

and has a

distinct folk

flavour in its

closing

section: this

provides

material for

the trio, a

shadowy affair

which opens in

C minor before

wending its

way to B flat

major.

The

robust,

vigorous

finale is

Haydnesque in

style but

constructed in

a typical

Mozartian

manner which

combines

characteristics

of rondo and

sonata form.

For

simplicity's

sake it is

probably easier

to regard it

as a

sonata-form

movement

without a

development. There

are two main themes

and a number

of episodes

related to the

business-like

first subject

which returns

in rondo

fashion until

the second

subject

appears in the

dominant with

an enchanting

little triplet

and emphatic

accents. The

"recapitulation"

begins after

an appropriate

pause and

presents all

the material

in cleverly

edited form.

QUARTET

IN B FLAT, K.

458 "THE HUNT"

The

B flat quartet

was completed

on November 9,

1784. While it

is associated

more with its

two successors

that its three

predecessors

(it is

possible that

the three

previous

quartets were

written before

Mozart

conceived the

idea of the

dedication),

there are some

coincidental

links with K.

421 - the

persistence in

places of the

folk flavour

of K. 421's

minuet and the

Haydnesque

nature of its

finale.

K.

458, one of the

most popular

of the set,

has been given

the nickname

"The Hunt"

because of the

theme of the

Haydnesque

first

movement,

which suggest

a hunting song

with its

galloping 6/8

rhythm, its

horn-like

phrasing, and

the soft

echoing of its

inner parts.

As usual

Mozart starts

with sonata

form, but this

time it is not

at all regular:

there is no

proper subject

and instead

the

development

begins with

what seems to

be a new theme

(it is, in

fact, a melodie

development)

in the

dominant key

of F major -

the key which

a normal

second subject

would have

had. Another

surprise is

the long coda

which

mischievously

begins like a

new

development

when one is

prepared for

the end of the

work at the

codetta in the

recapitulation.

The

second

movement is a

straighrforward

minuet and

trio,

presumably to

separate the

boisterous

good humour of

the first

movement from

the profundity

of the third.

The minuet's

easy grace is,

in fact, the

perfect

emotional

bridge to the

Adagio

in E flat,

which is the

real heart of

the work. Its

tender

eloquence is

combined with

latent power

in its harmony

and it has

many movements

of supreme

beauty,

particularly

in its second

theme. Here

the first

violin subtly

evades the key

of B flat on

which the

cello insists

when the theme

first appears

and then the

cello takes

over itself,

playing the

theme on its

golden upper

register.

The

finale in

sonata form

takes us right

back to the

Haydnesque

humour of the

first

movement.

Again the main

theme is

folk-like and

has a

resemblance to

the initial

hunting song.

The

development

concentrates

mainly on a

fugato

treatment of

the main

theme's second

phrase but

half-way

through we

come on a

sudden hushed

passage which

seems to mimic

the entry of

the Adagio's

second theme.

Unlike the

first movement

there is no

coda, a few

additional

phrases

sufficing to

bring the work

to an enphatic

close.

QUARTET

IN A, K.

464

The

A

major quartet,

completed on

January 10,

1784, was a

particular

favourite of

Beethoven,

which is not

surprising in

view of its

superb

craftsmanship

and unity. It

is sometimes

called "The

Drum" because

of a

distinctive

drumming bass

which emerges

in the third

movement, but

it could be

argued that

this is the

result of an

intricate

rhythmic

evolution,

which like

most of the

other

outstanding

features of

the work, begins

in embryo in

the first

movement. The

overall

pattern is the

division of

each subject

into two

sections (the

exception

being the

contrasting

third

movement) and

the

juxtaposition

of the two

parts in

counterpoint.

The first

movement has,

unusually, a

short subsidiary

theme in C

major which

introduces the

second subject

proper. The

expsition ends

with a

reference in

the codetta to

the main

theme's second

section and

significantly

this is

included in the

ultimate coda

in a prominent

position.

The minuet

which follows

(still in A),

is merely a

framework into

which Mozart

pours music

which is

sometimes

almost savage

in its

intensity. The

first part of

the main theme

is based on

the second

section of the

previous

movement's

second theme.

Both parts of

the minuet

end

with the

rhythmic

pattern of the

first

movement's

codetta figure

and this

appears yet again

at the end of

the romantic

trio theme

which offers

temporary

relief in its

lush,

swelling

harmony. The

real relief,

however, comes

in the third

movement which

is a theme and

variations.

The

tranquillity

of the

smonthly

flowing theme

extends to the

variations

which seem to

grow

increasingly

independet. In

the last

variation

before the

theme returns

the cello

breaks into

its cheerful

drumming

accompaniment

below the

sweetly moving

upper stringe.

The

finale, in

sonata form,

takes us back

to the first

principles of

the first

movement. The

main subject's

first section

has the

rhythmic form

of the opening

of the minuet

(it is, in

fact, an

inversion of

the minuet's

ancestor in

the first

movement). The

second section

has the

rhythmic form

of the second

section of the

first

movement's

main theme. It

was the heart

of this that

provided the

recurring

codetta figure

and it is the

heart that

Mozart wants

here. He

immediately

cuts it out

and lets it

stand alone.

Soon we hear a

familiar

throbbing from

the cello but

this time it

is a sinister

ostinato bass.

The second

subject (with

an antecedent

in the second

part of the

minuet) is so

late in

appearing that

Mozart lets it

fulfil a

double role in

providing the

codetta. In

the middle of

the

development we

suddenly find

ourselves back

in the lush

romantic

atmosphere of

the trio

theme, which

Mozart

recreates

harmonically

using the

material of

the main

theme's first

section.

QUARTET

IN C, K. 465

"DISSONANCE"

Only

four days

after

completing K.

464 Mozart had

finished the

"Haydn" set

with one of

the most

controversial

and puzzling

works in

chamber-music

history. Much

has been

written about

its

famous adagio

introduction

with its

dissonant

entries, which

seems out of

character with

the rest of

the work, but

its structural

significance

remains a

mystery. There

are some

pointers to

future

thematic

material but

strangely

there is as

much in common

with the

finale of the

previous

quartet (the

elements of

the main theme

are there, for

instance, over

the ostinato

bass). When

the Allegro

break into 4/4

we suddenly

find ourselves

out in the

sunshine in a

theme of

refreshing

simplicity.

The opening

phrase,

however,

centres round

the interval

of a third

which

eventually

dominates the

rocking

triplets of

the second

subject. The

important coda

uses a little

subsidiary

theme

originally

derived from

the second

part of the

main subject.

In

the second

movement there

are three main

elements, an extended

and

beautifully

balanced

melody (A), a

little bridge

figure

centring round

the third

which is

constantly

repeated (B),

and the second

subject which

recalls

certain

characteristics

of the

introduction

(C). The form

is ABCBABC,

like a rondo

but with B

recurring

instead of A.

When C

reappears,

however, it is

unexpectedly

repeated in a

revised form

and leads into

a coda which

combines the

bridge figure

with a little

subsidiary

theme on the

first violin -

fashioned

(as in the

first

movement) from

the second

part of the

first theme. The

minuet and

trio provide

with their

wide intervals

relief from

the close

working of the

previous

movement.

Significantly

the minuet

ends with

another of

those singing

closes on the

first violin.

The

finale has a

brisk,

carefree main

theme. The

second subject

emerges

initially as a

duet for the

violins. The

first violin

then goes

dancing in G

major through

a maze of

semiquavers

towards the

codetta. But

suddendly as

it emerges on

a lone D there

is a stunning

modulation to

E flat (using

the Neapolitan

sixth) and

we are in the

middle of what

seems like a

new theme. It

is, however,

the codetta

and the

"theme" is a

cleverly

disguised

version of the

opening of the

first subject.

Following the

pattern of the

previous

movements

Mozart should

have used it

in the final

coda, but by

using it here

he can

resummon it

eventually.

This he does,

letting the

cello join in

too, and he

follows it

up with a good

old-fashioned

theatrical-style

coda - a rare

occurrence in

his mature

chamber music

- so ending

the work, and

the set, with

a fine

flourish.

A.

David

Hogarth

QUARTETTO

ITALIANO

The Quartetto

Italiano is

deservedly one

of the most

renowned

quartets of

our time. It

was as long

ago as 1945,

soon after

completing

their studies,

that Paolo

Borciani,

Elisa

Pegreffi,

Piero Farulli,

and Franco

Rossi,

resisting the

tempting

promise of

individual

careers as

soloists,

decided to

pool their

youthful

enthusiasm and

musical talent

and devote

themselves to

the difficult

but satisfying

art of playing

chamber music

really well.

By 1947 the

group had

established a

firm

reputation in

the musical

press and

begun giving

concerts

outside Italy.

In 1951 they

visited the

United States

for the first

time, and it

was soon

apparent that

their devotion

to their music

and the

impeccable

standards of

performances

they had set

for themselves

were earning

them fame as

well as

satisfaction.

Over the years

since 1945

they have

remained

together, a

rare example

of team work

in music.

To list the

group’s

wide-ranging

activities in

that time is

pointless:

they have done

everything one

might expect

of one of the

world’s finest

quartets. They

have given

hundreds of

concerts all

over Europe

and in the

United States;

they are

regular

partecipants

in the

chamber-music

concours of

many

countries; and

they have

played and are

in constant

demand at the

world’s great

music

festivals.

Outside the

concert

circuit the

members of the

quartet teach

chamber music

at both the

Royal Academy

of Music in

Stockholm and

the

Conservatoire

in Vienna.

In addition to

the many words

of praise

bestowed on

them – after

their first

concert in New

York, Virgil

Thomson, the

distinguished

critic of the

“New York

Herald

Tribune,”

called them

“the finest

quartet,

unquestionably,

that our

century has

known” – they

have been

publicy

honoured by

the President

of Italy as a

more tangible

recognition of

their

outstanding

artistic

services over

the years to

Italy in

particular and

the world of

music in

general.

|

|

|