|

|

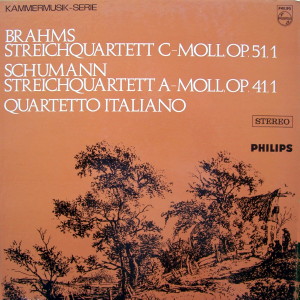

Philips

- 1 LP - 802 815 - (p) 1968

|

|

| Philips

Duo - 2 CDs - 456 320-2 - (c) 1997 |

|

| Decca -

37 CDs - 478 8824 - (c) 2015 |

|

| Johannes Brahms

(1833-1897) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

String

Quartet No. 1 in C minor, Op. 51,

No. 1

|

|

33' 41" |

|

| -

Allegro |

11' 18" |

|

|

| -

Romance (Poco adagio) |

7' 24" |

|

|

| -

Allegretto molto moderato e

comodo - Un poco più animato |

8' 35" |

|

|

| -

Allegro |

6' 06" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Robert Schumann

(1810-1856) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| String

Quartet No. 1 in A minor, Op. 41,

No. 1 |

|

25' 51" |

|

-

Introduzione (Andante

expressivo - Allegro)

|

9' 41" |

|

|

-

Scherzo (Presto) -

Intermezzo

|

3' 42" |

|

|

| -

Adagio |

5' 55" |

|

|

| -

Presto |

6' 17" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

QUARTETTO

ITALIANO

- Paolo Borciani, Elisa Pegreffi, violino

- Piero Farulli,

viola

- Franco Rossi, violoncello

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione |

|

Théâtre

Vevey, Vevey (Svizzera)

- 18-31

agosto 1967 |

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Vittorio

Negri | Tony

Buczynski |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Philips | 802

815

| 1

LP | (p) 1968

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Philips Duo | 456 320-2

| 2

CDs - 71'

55 -

75' 21" - (1°,

1-4) | (c)

1997 | ADD | (Brahms)

Decca | 478 8824 |

37 CDs - (33°, 1-4) | (c)

2015 | ADD | (Schumann)

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

The fact

that Brahms left us only three

string quartets and delayed

publication of the first (the

one we hear here) until 1873

when he was 40 years old can

be blamed in a way on

Schumann. For iy was Schumann

who championed the young

Brahms before he became

established as a composer.

Indeed he regarded him as

something of a musical Messiah

- "This is he that should come," he wrote to

his friend Joseph Joachim,

meaning that he saw in

Brahms the true heir to

Beethoven's throne. These

sentiments he soon made

public in an article in the

"Neue Zeitschrift für

Musik" in 1853 when Brahms

was only 20 and had not yet

had anything published.

However

right Schumann was in his

predictions, they placed

an almost intolerable

burden of responsibility

on the young composer's

shoulders in living up to

his glowing image. The

result was a ruthless

self-critical attitude

toward his own work -

particularly in the fields

of the symphony and the

string quartet, those

areas of the art in which

Beethoven was supreme. But

one should not imagine

that Brahms as a result

lacked confidence in his

own ability. He knew that

he could never be

Beethoven's equal, but he

knew that with diligence

he could (and did) become

a worthy successor. If he

was afraid of comparison

of his works with those of

Beethoven, he was never

afraid of the shadow of

Beethoven itself. His work

(and this first quartet in

particular) constantly

acknowledges Beethoven as

his master and guiding

light in a perfectly frank

way. Nor was he afraid of

tackling string quartet

writing. We know from his

correspondence

that he wrote about

twenty other quartets

before the C Minor, none

of which passed his

rigorous self-set

standards, though many

must surely have been

masterpieces. The C

Minor Quartet,

then, is not the first

of Brahms' string

quartets, but rather the

first that he chose to

let posterity hear. When

we consider the

composer's complete

artistic integrity, that

in itself is surely recommendation

enough of its

greatness.

Strangely

Schumann too

published only three

string quartets, but

it was enthusiasm

rather than

hesitance that led

to them, Schumann

was a man of sudden

and violent

enthusiasms and most

of his work can be

classified in

periods which

coincide with

successive

preoccupations.

First, and probably

foremost, he was a

composer of piano

music. Then in 1840

came the great flood

of songs. The

following year 1841

was the year of

orcgestral works.

Chamber music

followed in 1842

with all three

string quartets

being written in

June of

that year.

If any

boubts remained in

some people's

minds about

Schumann's true

genius as a

composer, the

quartets settled

the matter. They

are not slavish

copies of

"traditional"

style and form but

highly original in

conception. While

in the A Minor

Quartet we

often see him

thinking in terms

of piano writing,

this does not

detract from the

work's quality as

a quartet any more

than Brahms'

orchestral

thinking detracts

from his.

Mendelssohn

who had

previously

tended to treat

Schumann's

talent rather

lightly in his

good-natured

way, was among

those deeply

impressed by the

work and the

distinguished critic,

Moritz

Hauptmann

summed up

critical

reaction in a

letter to the

composer

Spohr: "At

David's

(Ferdinand

David, the

German

violinist,

composer, and

conductor) I

heard three

quartets of

Schumann's:

his first,

which pleased

me greatly

indeed, made

me marvel at

his talent,

which I

thought by no

means

remarkable,

judging from

his previous

pianoforte

pieces..."

BRAHMS:

STRING QUARTET

IN C MINOR,

OP. 51, NO. 1

First

movement:

The sombre,

almost tragic

first movement

is a towering

structure,

built

characteristically

from the

smallest

of thematic

bricks. First

is a typical

stabbing

figure which

rises with

growing

vehemence and

is soon

combined with

a lyrical

tripler

passage shared

by the

violins. The

second

thematic group

opens with

descending

thirds

combined with

hesitant

quaver groups

which soon

dominate the

music like the

famous motif

of Beethoven's

Fifth

Symphony. The

stabbing

rhythms return

in the

descending

intervals

before another

lyrical

subject

appears on the

first violin

as a

counterpart to

that in the

first section

and brings the

esposition

down to gentle

rest. The

development is

a terse

treatment of

the opening

motifs of the

two subject

groups and the

recapitulation

varies the

presentation

of the

original

material in

masterly

fashion.

Second

movement:

The air of

defiance

becomes one of

deep

melancholy in

the superbly scored

Romanze

which is in

simple ABA

form. The

essential

elements of

subject A

inevitably

recall the

theme of the

slow movement

of Beethoven's

Violin

Concerto and

the sobbing

subject B has

much in common

with the Cantilena

of Beethoven's

Op. 130

Quartet. The

gloriously

rich

treatment,

however is

complete

Brahms. The

first melody

is skilfully

brought back

in a

beautifully

varied version

and the

movement ends

with extended

references to

B and A in

turn.

Third

movement:

The scherzo in

F Minor is one

in name only.

It sidles

along warily

and uneasily

in its first

section,

finally

plucking up

enough courage

to sing in the

second section

before the air

of suspicion

returns with

the first

theme. All

this lends a

radiance to

the simple

trio in the

major and

makes its

plodding

pizzicatos

seem almost

cheerful.

Fourth

movement:

The short

finale sums up

concisely the

whole work

both

emotionally

and

thematically

Brahms uses a

sonata-rondo

form but

telescopes it

and adapts it

considerably.

Everywhere

there are

echoes of the

previous

movements.

Most obvious

is the unison

opening

with the same

stabbing

rhythm and

final falling

interval as

the opening of

the first

movement. The

actual notes,

however are

those which

open the Romanze.

This

motif recurs

with almost

fateful

persistence,

more often

than strict

form requires

and often in

subtle

disguises. The

boldest break

with tradition

is the way

Brahms creates

and relieves

tension by

keeping us

away from the

home key until

a final "full

dress"

appearance of

the main

theme, which

takes us into

the vigorous

coda.

SCHUMANN:

STRING QUARTET

IN A MINOR,

OP: 41, NO. 1

First

movement:

Schumann

introduces his

instruments

one by one in

a finely

wrought

contrapuntal

introduction.

The Allegro

begins in F

major with the

first subject,

a lyrical

theme with a

characteristic

displaced

accent. The

important

final phrase

swells up on

the cello

again as we

move into the

bridge section

where the

viola begins a

fugato passage

based on the

main theme.

Soon we move

to the

dominant key,

but where one

might wxpect a

contrasting

second

subject, the

final phrase

of the first

appears

staccato on

the viola. It

is taken up by

the second

violin and

continues to

form what is,

in fact, the

second

subject. The

opening of the

main theme

then returns

in the

codetta.

Second

movement:

Although the

theme of the Scherzo

is derived

from a trio by

the now

largely

forgotten

composer

Heinrich

Marschner, it

seems typical

Schumann and,

indeed, was

later used

again as the

accompaniment

of one of his

songs. The

scampering

scherzo

itself,

handled with

Mendelssohnian

puckishness,

is in three

sections. As

his Intermezzo,

Schumann uses

a little

musette in C

major, with

the cello

providing the

"bagpipe"

drone: the

theme is

derived from

the previous

movement's

first subject.

Third

movement:

A short

introduction

leads into the

song-like

theme of the Adagio

in F major,

which the

viola

accompanies

with

piano-like

arpeggios.

These develop

into a rolling

figure as the

cello takes

over the first

part of the

theme. A move

to A-flat

disturbs the

calm

as the

arpeggios

begin to rise

and fall from

one instrument

to another.

The rolling

figure then

begins to pass

to and fro

between viola

and second

violin before

the theme

re-emerges on

the first

violin. The

movement ends

with the

reappearance

of the

introduction

as a postlude.

Fourth

movement:

The key to the

finale lies in

the three bold

opening notes,

for Schumann

uses them to

establish yet

again a

relationship

between his

first and

second themes.

The first,

stated

immediately,

reminds us of

the scampering

thirds of the

Scherzo.

After a bridge

motif, the

first theme

undergoes

steady

trasnformation,

becoming more

martial until

we find it

changed into

the second

subject, which

begins with an

inversion of

the movement's

three opening

notes and goes

striding on

boldly. In the

development

Schumann again

emphasizes the

link between

his subjects.

He then

handles his recapitulation in

a novel manner, omitting the

first subject and beginning

with the bridge. Only after

the second subject has taken

its normal place is the first

theme recalled. The final

surprise is a sudden lull for

a longer version in A Major of

the little musette before we

plunge into the coda.

|

|

|