|

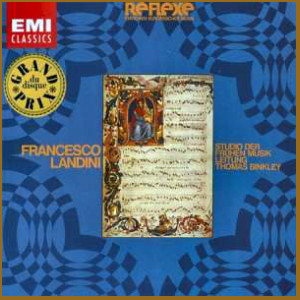

1 LP -

1C 063-30 113 - (p) 1973

|

|

1 CD - 8

26481 2 - (c) 2000

|

|

| Francesco

Landini (1325-1397) |

|

|

|

|

|

| - I. Che pena è

quest' al cor - Sängerin,

Sänger und Fiedel |

4' 13" |

|

| - I' priego amor

- Laute, Diedel und Organetto |

2' 30" |

|

| - II. Donna, s'i

t'o fallito - Sängerin und

Sänger |

3' 04" |

|

| - III. Adiu,

adiu, dous dame - Sänger,

Laute und Fiedel |

2' 26" |

|

| -

IV. Ma' non s'andra - Sängerin

und Lira |

3' 28" |

|

| -

V. Una colonba candida - Sängerin

und Sänger |

4' 02" |

|

| -

VI. O fanciulla giulía - Sängerin,

Rebec und Douçaine |

5' 16" |

|

|

|

|

| - VII. Chosi

pensoso - Sängerin, Sänger

und Posaune |

2' 00" |

|

| - VIII. De!

dinmi tu - Sängerin,

Sänger und Douçaine |

1' 55" |

|

| - IX. Questa

fanciull' amor - Sängerin,

Sänger und Fiedel |

3' 31" |

|

| -

Questa fanciull' amor

(anonym, Codex Reina) - Organetto

und Douçaine |

1' 59" |

|

| - X. Non avrà

ma' pieta - Sängerin,

Fiedel und Citole |

4' 25" |

|

| - Non avrà ma'

pieta (anonym, Codex Faenza) -

Laute und Harfe |

3' 37" |

|

- XI. Gram

piant' agli occhi - Sängerin,

Sänger und Citole

|

5' 39" |

|

|

|

|

STUDIO DER FRÜHEN

MUSIK / Thomas Binkley, Leitung

|

|

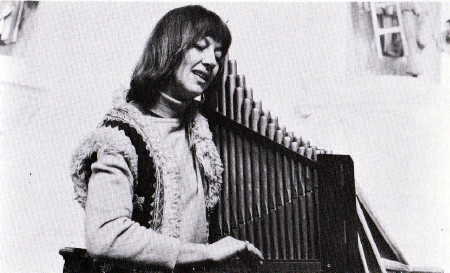

-

Andrea von Ramm, Sängerin,

Organetto, Harfe

|

|

| -

Richard Levitt, Sänger |

|

-

Sterling Jones, Fiedel, Lira,

Rebec

|

|

| -

Thomas Binkley, Laute, Douçaine,

Citole, Posaune |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Bürgerbräu,

Münich (Germania) - gennaio 1972 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Gerd

Berg / Wolfgang Gülich

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

EMI

Electrola "Reflexe" - 1C 063-30

113 - (1 lp) - durata 48' 25" -

(p) 1973 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - 8 26481 2 - (1 cd) -

durata 48' 25" - (c) 2000 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

FRANCESCO

LANDINI FRANCESCO

LANDINI

Who was this man?

Villani, the chronicler of

Florence, wrote about his

life, and he is mentioned here

and there in the belles lettres

of his contemporaries.

Giovanni da Prato describes

his performances in the

gardens of the Villa Alberti,

Cino Rinuccini makes a sober

statement of his qualities,

the Florentine poet Franco

Sacchetti communicated with

Landini in verse, Simone

Prudenzani places several

pieces of Landini’s in the

Christmas celebration of his

master entertainer, Sollazzo.

Landini was presented with the

laurel by Peter the Great,

King of Cyprus, for his

poetry.

Landini’s Italy was not our

Italy. It

was a more personal Italy,

lacking green hills and

sunlight, wine terraces and

landscapes. It

was private world of sound and

abstract ideas, for Landini,

il cieco, was blind.

Francesco Landini, son of the

painter Jacopo (del

Casentino?) and contemporary

of Petrarch, was blinded in

childhood by smallpox. He was

a pupil of Jacopo da Bologna

and was a skilled performer on

many instruments, particularly

the organ. Francesco Landini,

the blind organist of the

church of San Lorenzo in

Florence is without doubt the

best known name in Italian

fourteenth-century

music. One hundred and fifty

three secular works have

survived to demonstrate his

prominence in the anthologies

of the period, more than three

times the number of any other

composer in any country save

Machaut, who collected his own

works.

Landini was a master musician

(performer), composer and

poet, and a dabbler in

philosophy and astrology as

well. If

one were to walk from Fiesole

to Florence, the first large

church one would encounter is

that of San Lorenzo, where

Landini was organist.

He was not organist at the

giant Cathedral of Santa Maria

del Fiori with the so-called

Giotto Campanile, for although

construction was under way, it

was neverfinished in his

lifetime. Nor for that matter

was the work of Brunelleschi,

nor that of Michelangelo on

his own San Lorenzo to be seen

during his lifetime.

Landini’s San Lorenzo was the

4th-century church consecrated

by St. Ambrose, restored in

the 12th century and then,

under the influence of the

Medici family, and just

shortly after Landini’s

tenure, rebuilt, mostly by

Brunelleschi.

We have very little idea of

what our blind organist played

in his San Lorenzo, for only a

fragment of one scared piece

has come down to us, which is

a motet.

Landini must have known

Giotto, the peasant son

painter who was so well

adjusted to his age that he

never participated in nor

suffered, as did his friend

and benefactor Dante, from the

complicated politics of

Florence. Landini was serious

in spirit, and his was the

intellectual world, in which

he participated as a younger

contemporary of Petrarch and

Boccaccio - there we have an

unequalled Trio: Dante,

Petrarch, Boccaccio, and to

them we add the less-known

Sacchetti and indeed many

others of literary quality and

fame. But Landini was not the

type for the lighthearted. Novella

of Boccaccio or Sacchetti.

Landini was earnest. Dance

music does not figure in his

secular composition, nor was

popular music a part of his

world, and he held it in

derision.

He wrote:

Musica son’

che mi dolgo piangendo

Veder gli

effecti mie dolcie profecti

Lasciar

perfrottol’ i vagh'

intellecti.

(I am

Musica, and it pains me to

tears

to see the

effects of my own sweet

prophets

ignored by

the best minds for pop-tunes.)

None of Landini’s texts are

easily witty, nor light of

heart, bawdy or otherwise

directly entertaining. The

texts of his ballate are

mostly his own (unlike many of

his colleagues’)

and are set (with one

exception) to very serious

music. Well now, how do we

account for the fact that

people collected over 150

serious songs of this man,

songs which are both difficult

to perform and highly

demanding on the listeners? It

was not out of reverence for

his name, it was because of

certain qualities in his texts

and music, qualities which we

must discover both as

performers and as listeners to

his music.

Here we see a sign of changing

taste. We are reminded of the

troubadour Arnault Daniel of

whom Petrarch wrote: “gran

maestro d’amor, ch’alla sua

terra amor fa onor, col suo

dir strano e bello" and who

Dante praised as “miglior

fabbro del parlar materno",

whose rhymes were more

original than any other, whose

songs, according to the razo,

were neither easy to

understand nor easy to learn.

"Who", asked Bornart Amoros,

"will be so subtle as to

understand everything,

especially in the songs of

Giraut de Bornelh?" So it is

with Landini, whose music is

difficult to understand and

difficult to learn, however

potent.

The Trecento Italian found in

his music a synthesis of the

art world rapidly changing, a

concentrate of the essence of

the cultural life-style at the

moment it passed over the

brink. As a serious artist,

Landini reflected two

generations of music; it is as

if he were a late-comer to the

next scene.

It

would be unfair and frivolous

to discuss Landini’s music in

terms of his cadences or

treatment of dissonance. This

would be to discuss the

paintbrush of the painter. The

artistry of his music is to be

found beyond the techniques he

employed. Landini’s was a

world of sounds and ideas, and

his music is of immense depth,

never frivolous, seldom even

really light-hearted, actually

rejecting all simple and clear

emotions, yet suggestive, warm

and personal.

He must have been a

fascinating man to know. To

paraphrase his tombstone, his

ashes lie in San Lorenzo, his

soul above the stars, but his

music remains with us.

Thomas

Binkley

|

|

|

EMI Electrola

"Reflexe"

|

|

|

|