|

1 LP -

1C 063-30 121 - (c) 1974

|

|

| 1 CD - 8

26490 2 - (c) 2000 |

|

2 CD -

CMS 7 63421 2 (Carissimi) - (c) 1990

|

|

| GIACOMO CARISSIMI (1605-1674)

- Dives Malus (Historia Divitis) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Gregorio

Allegri (1582-1652) |

|

|

| Symphonia in G

für Streicher und Basso continuo |

4' 47" |

|

|

|

|

| Giacomo

Carissimi (1605-1674) |

|

|

| DIVES MALUS

(HISTORIA DIVITIS) - Oratorium

für Soli, Chor, Streicher und Basso

continuo |

|

|

| - Erat vir

quidam opulentissimus - Historicus

(Sopran I) |

2' 33" |

|

| - Factum est

autem ut moreretur - Historicus

(Sopran II) |

1' 05" |

|

| - Iam satis

edisti - Soli und

Chor |

2' 59" |

|

| - Heu miser,

quid audis? - Dives (Tenor

I), Soli und Chor |

1' 17" |

|

| - O spes meas

fallaces - Dives, Sopran

I, Tenor II, Baß II, Sopran II |

2' 52" |

|

| - Morere,

infelix! - Soli und Chor |

1' 34" |

|

- Sat mensas

mille plenas - Sopran II,

Tenor II, Cantus II, Cantus I,

Soli und Chor

|

2' 18" |

|

|

|

|

| - En vitae

suprema - Sopran II,

Sopran I |

3' 57" |

|

| - Heu me miserum

- Dives, Soli und

Chor |

4' 40" |

|

| - Mortuus est

ergo dives, et sepultus - Historicus

(Tenor I) |

0' 48" |

|

| - Pater

Abraham, miserere mei - Dives,

Abraham |

2' 37" |

|

| -

O dives miserrime - Soli

und Chor |

3' 45" |

|

| -

Quam stulti sunt, quam vani -

Soli und Chor, Tenor II |

1' 58" |

|

| -

Avernales inter poenas - Tenor

II |

3' 55" |

|

|

|

|

| VOKALENSEMBLE DER

SCHOLA CANTORUM BASILIENSIS |

|

-

Sheila Armstrong, Sopran

|

|

| -

Eva Csapò, Sopran |

|

| -

Nigel Rogers, Tenor |

|

| -

Ian Partridge, Tenor |

|

| -

Kurt Widmer, Baß |

|

| -

Matthias Hölle, Baß |

|

|

|

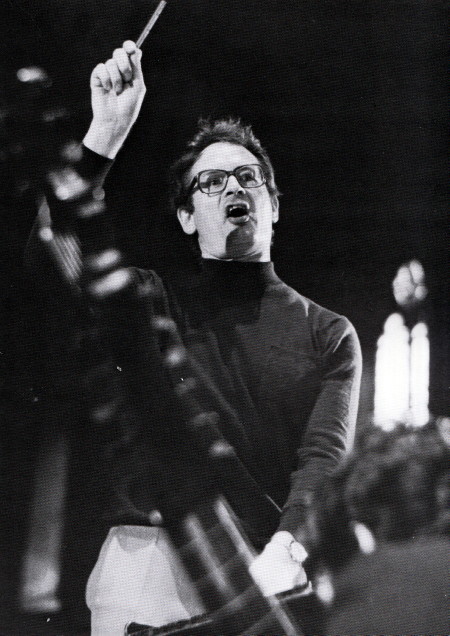

| LINDE-CONSORT

/ Hans-Martin Linde, Leitung |

|

| -

Herbert Höver, Miguel de la Fuente,

Adelheid Schäfer, Christopher

Schmidt, Zukimi Kambe, Violine

alter Mensur |

|

| -

Dorothea Jappe, Violine und

Viola alter Mensur |

|

| -

Michael Jappe, Violoncello alter

Mensur |

|

| -

Angelo Viale, Violone |

|

| -

Dieter Kirsch, Theorbe |

|

| -

Konrad Ragossnig, Laute |

|

| -

Toyohiko Satoh, Chitarrone |

|

| -

Gottfried Bach, Cembalo

(Eckehart Merydorf, nach Daniel

Dulcken, 1755) |

|

| -

Eduard Müller, Orgelpositiv

(Bernhard Fleig, Hersberg) |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Tituskirche,

Basel (Svizzera) - 26-30 aprile

1974 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Gerd

Berg / Johann-Nikolaus Matthes /

Wolfgang Gülich

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

EMI

Electrola "Reflexe" - 1C 063-30

121 - (1 lp) - durata 41' 13" -

(p) 1974 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - CMS 7 63421 2 - (2

cd) - durata 58' 41" - 63' 07" -

(c) 1990 - ADD - (Carissimi)

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - 8 26490 2 - (1 cd) -

durata 41' 13" - (c) 2000 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

In

the historia divitis

Carissimi combined the

scriptural history on the rich

man with dramatic passages

that embellish the story in a

nearly theatrical way. In

these sections favorite and

cappella choir - partly

engaged in dialogue with the dives

- unite and from great sound

blocks. The narration by the historicus

and the words by the

characters (Dives, Abraham)

are relatively simple, but

most impressive solo

declamations with figured bass

accompaniment. A third element

is given by comtemplative and

didactic passages which demand

the novel type of cantare

con affetto. The result

of these contrasts is a

charming combination of the

rather traditional double

choir style with modern

monody, of plain, but ever

impressive harmony with casual

chromatic passages, of complex

sound with line. The

performers are supposed to

achieve the plasticity of a

‘didactic play’ by means of

deliberately formed contrasts.

Again and again the soloists

must decide which is the

appropriate dimension and

significant distribution of

intesifying means in

performance (such as

ornamentation, dynamic and

agogic accent). The

distribution ofthe figured

bass as well - which the

composer has not written in

full - must contribute to the

deepening of the contents of

the biblical text and the

poetical work. In the

present recording the theorbo

and lute were employed as

ornamenting instruments.

According to Agazzari (1607)

this means “the running up and

down of the fingers on the

strings”, that is the bass

line is ornamented for the

embellishment of the sound

picture. The organ, chitarrone

and partly the harpsichord

were more frequently employed

as ground instruments. In the

corresponding parts of the

composition the provide a

calm, all-combining colour. In the

solo parts each character is

given typifying continuo

accompaniment. Some

ornamental, text-interpreting

figures have been written in

full by the composer. In most

cases, however, the singer

himself must find the

appropriate means of

performance (such as rising

and sinking voice,

coloratura). They result from

the right understanding of the

text and the knowledge of

contemporary sources. The part

of the strings is still small

in Carissimi. It is

mostly confined to ritornels

with organizing function in

form and intensification of

the tutti. In

the historia divitis

Carissimi combined the

scriptural history on the rich

man with dramatic passages

that embellish the story in a

nearly theatrical way. In

these sections favorite and

cappella choir - partly

engaged in dialogue with the dives

- unite and from great sound

blocks. The narration by the historicus

and the words by the

characters (Dives, Abraham)

are relatively simple, but

most impressive solo

declamations with figured bass

accompaniment. A third element

is given by comtemplative and

didactic passages which demand

the novel type of cantare

con affetto. The result

of these contrasts is a

charming combination of the

rather traditional double

choir style with modern

monody, of plain, but ever

impressive harmony with casual

chromatic passages, of complex

sound with line. The

performers are supposed to

achieve the plasticity of a

‘didactic play’ by means of

deliberately formed contrasts.

Again and again the soloists

must decide which is the

appropriate dimension and

significant distribution of

intesifying means in

performance (such as

ornamentation, dynamic and

agogic accent). The

distribution ofthe figured

bass as well - which the

composer has not written in

full - must contribute to the

deepening of the contents of

the biblical text and the

poetical work. In the

present recording the theorbo

and lute were employed as

ornamenting instruments.

According to Agazzari (1607)

this means “the running up and

down of the fingers on the

strings”, that is the bass

line is ornamented for the

embellishment of the sound

picture. The organ, chitarrone

and partly the harpsichord

were more frequently employed

as ground instruments. In the

corresponding parts of the

composition the provide a

calm, all-combining colour. In the

solo parts each character is

given typifying continuo

accompaniment. Some

ornamental, text-interpreting

figures have been written in

full by the composer. In most

cases, however, the singer

himself must find the

appropriate means of

performance (such as rising

and sinking voice,

coloratura). They result from

the right understanding of the

text and the knowledge of

contemporary sources. The part

of the strings is still small

in Carissimi. It is

mostly confined to ritornels

with organizing function in

form and intensification of

the tutti.

Hans-Martin

Linde

Translation

by Gudrun Meier

The orgins of oratorio are

closely bound up with the lay

piety which was particularly

marked in Italy and which gave

rise, in the 13th century, to

the founding of organised

fraternities. “Oratorio” first

denoted the chapel, or

oratory, in which the members

of the order gathered to sing

and worship. Music played a

major part in these devotions,

and it was in this setting

that, in Rome in the first

half of the 17th century, the

gradual evolution of oratorio

as a musical form came about.

The form had various

antecedents, the most

important of these being the

religious dialogue set to

music. Whereas the “oratorio

volgare", sung in italian,

attracted a wide public to S.

Maria

in Vallicella, the tradition

of the “oratorio latino” was

fostered at the church of S. Marcello

by the “Arciconfraternita del

SS. Crocifisso", a socially

and intellectually more

exclusive community which had

been active since 1526. The

Italian oratorio acquired a

widespread following in the

course of the 17th century,

both in Italy

itself and abroad, but the

Crocifisso Fraternity’s

“oratorio” maintained its

position at the centre of the

form’s Latin branch. Among the

composers of oratorio latino

an equally central role was

played by one person: -

Giacomo Carissimi. He was

born in Marino

(Castelli Romani) in 1605, the son

of a fairly prosperous cooper,

and had held posts in the

cathedrals of Tivoli

(1623-1627) and Assisi

(1627-1629) before being

appointed music teacher and

Kapellmeister of the

Sant’Apollinare church at the

Jesuit Collegium Germanicum Hungaricum

in Rome. Here he was to spend

the rest of a life crowned

with fame and success (the

latter also in financial terms

- much,

to quote a peevish remark by a

member of the college, to his

detriment).

Carissimißs Latin oratorios

represent at once the

beginning of the genre and its

zenith. But he was not its

creator. The first dawning of

both the Latin and Italian

oratorio is somewhat obscure,

since the earlier, traditional

material surviving is both

scant and fragmentary.

Moreover,

like the oratorios of

Carissimi himself, it can

hardly be dated. However,

we do know, from the French

traveller André Maugars

1639 account of the Crocifisso

Fraternity’s performances,

that these were then already

an established institution -

suggesting that they must have

started considerably earlier.

Maugars

contrasts the Sant‘Apollinare

performances with the

grandiose presentations at S.

Maria

sopra Minerva (with no less

than ten choirs positioned

around the church) and refers

to them as a “different sort

of music”, known as the “stile

recitativo”.

The service would begin with a

psalm motet, followed in turn

by an instrumental piece, a

story from the Old Testament,

a sermon and, finally, the

day’s reading from the

Gospels, the two Biblical

texts being rendered musically

with parts assigned. If

Carissimi, in these

“recitativo" parts, is

standing on ground provided by

the later works of Monteverdi,

the choruses - which, though

not mentioned by Maugars,

are nonetheless important in

Carissimi - show the lingering

influence of the Palestrina

and polychoral Venetian

styles.

Carissimi was not an

innovator; his musical

resources were simple, but

used with perfect mastery and

artistic ingenuity. In the

baroque era the art of

faithfully reproducing the

spoken word in music was held

to be one of a composer’s

highest attributes. And it is

for this merit above all that

Carissimi’s works have, all

along, earned fame and

admiration. Just as, on the

formal plane, both individual

word accentuation and the

broader grammatical groupings

are perfectly rendered,

so, too, where content is

concerned, are the individual

concepts and the greater

bodies of meaning transcending

these. All this makes Giacomo

Carissimi doubly deserving of

our acclamation as the master

of musical oratorio.

Theophil

Antonicek

Translation

by R. C. Sigee

In accordance with

contemporary practice the

performance of the oratorio

Dives Malus by Carissimi

was preceded by that of the

Symphonia in G by Gregorio

Allegri. |

|

|

EMI Electrola

"Reflexe"

|

|

|

|