|

|

1 CD -

453 170-2 - (p) 1996

|

|

50

Jahre (1947-1997) - Codex I Serie - 9/10

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

VIOLIN CONCERTOS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Giuseppe

TARTINI (1692-1770)

|

Violin

Concerto in D major

|

|

13' 31" |

|

|

-

Allegro

|

4' 01" |

|

1 |

|

-

[Intermezzo]

|

0' 30" |

|

2 |

|

-

Andante cantabile |

5' 05" |

|

3 |

|

-

Allegro assai

|

3' 55" |

|

4 |

|

Violin

Concerto in G major |

|

16' 18" |

|

|

-

[Andante] |

6' 35" |

|

5 |

|

-

Largo andante - Grave |

4' 45" |

|

6 |

|

-

Presto |

4' 58" |

|

7 |

| Pietro NARDINI

(1772-1793) |

Violin

Sonata in D major *

|

|

15' 08" |

|

|

-

Adagio

|

6' 35" |

|

8 |

|

-

Allegro |

5' 41" |

|

9 |

|

-

Allegro

|

2' 52" |

|

10 |

|

Violin

Concerto in E flat major |

|

22' 27" |

|

|

-

Allegro |

9' 17" |

|

11 |

|

-

[Andante] |

5' 07" |

|

12 |

|

-

Allegro |

8' 03" |

|

13 |

|

|

|

|

Lionel Salter,

fortepiano *

Eduard Melkus, violin

CAPELLA ACADEMICA WIEN

August WENZINGER

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Studio

Wien-Film, Rosenhügel, Wien

(Austria) - 11-14 febbraio 1966

(Concertos)

Palais Schönburg, Wien (Austria) -

26-29 gennaio 1971 (Sonata)

|

|

|

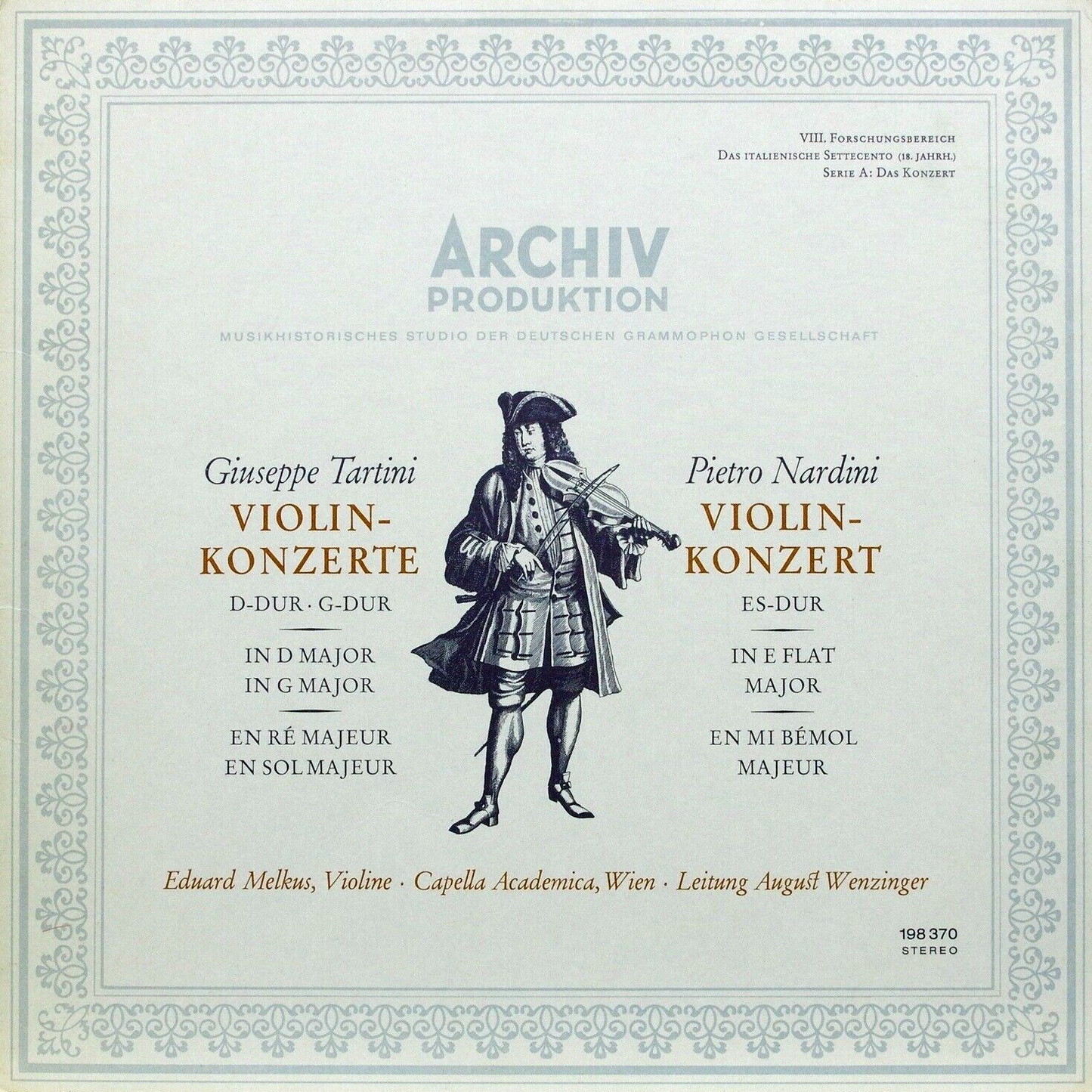

Original

Editions |

|

-

Archiv Produktion | 198 370 | 1 LP

| (p) 1967 | ANA | (Concertos)

- Archiv Produktion | 2533 086 | 1

LP | (p) 1972 | ANA | (Sonata)

|

|

|

Edizione

"Codex"

|

|

Archiv

Produktion "Codex" | 453 170-2 |

durata 67' 40" | LC 0113 | 1 CD |

(p) 1996 | ADD | stereo

|

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

Prof.

Dr. Hans Hickmann (Concertos); Dr.

andreas Holschneider (Sonata)

|

|

|

Recording

Producer |

|

Dr.

Gerd Ploebsch

|

|

|

Tonmeister

(Balance Engineer) |

|

Harald

Baudis (Concertos); Hans-Peter

Schweigmann (Sonata)

|

|

|

Recording

Engineer

|

|

Hans-Rudolf

Müller (Sonata)

|

|

|

Cover |

|

Pierre

Subleyras: Fantaisie d'artiste,

les attributs des Arts (detail),

Musée des Augustins

|

|

|

Art Direction

|

|

Fred

Münzmaier

|

|

|

Note |

|

Original-Image-Bit-Processing

- Added presence and brilliance,

greater spatial definition |

|

|

|

|

|

ORIGINAL

EDITIONS

1 LP - 198 370 - (p) 1967

1 LP - 2533 086 -

(p) 1972

1 LP - 2533 086 -

(p) 1972

|

Treasures

from Archiv Produktion’s

Catalogue

A rare and valuable collection of

documents is the pride of any

library or archive. CODEX, Archiv

Produktion’s new series, presents

rare documents in sound from 50

years of pioneering recording.

These recordings have been

digitally remastered using

original-image bit-processing

technology and can now be

appreciated in all the richness of

their original sound-image. They

range from the serene counterpoint

of a Machaut, the intensely

spiritual polyphony of a Victoria,

to the imposing state-music of a

Handel.

For the artists on Archiv

Produktion recordings, a constant

aim has been to rediscover the

musical pulse of past times and to

recreate the spirit of past ages.

In this sense each performance

here - whether by Pro Musica

Antiqua of Brussels in the 1950s,

the Regensburg Domchor in the

1960s, or Kenneth Gilbert and

Trevor Pinnock in the 1970s - made

a vital contribution to the

revival of Early Music in our

time.

CODEX highlights recordings that

were unique in their day, many of

them first recordings ever of this

rare and remarkable repertoire,

now appearing for the first time on

CD. A special aspect of the

history of performance in our

century can now be revisited, as

great moments from Archiv

Produktion’s recording history are

restored and experienced afresh.

Dr.

Peter Czornyi

Director,

Archiv Produktion

TARTINI - NARDINI: Violin

Concertos · Violin Sonata

Giuseppe Tartini, who was born at

Pirano in 1692 and died at Padua

in 1770, is of great interest not

only as one of the foremost

violinists of the 18th century,

but also as a composer, and as the

founder of a system of violin

playing which spread throughout

Europe, pointing forward to the

violin technique of modern times.

Another violinist Whose influence

was far-reaching was Tartini’s

pupil Pietro Nardini, who was born

at Livorno in 1722 and died at

Florence in 1793. He, together

with Locatelli, probably did most

to prepare the ground for the

virtuoso technique of Paganini,

and as a composer he was important

in connection with the evolution

of Viennese Classicism.

The violinist of today is strongly

attracted to early music. For one

thing the technical and tonal

challenge is fascinating, as

he/she attempts to revive the

ancient technique of playing a

short-necked violin with an

old-style bow, which has its own

interpretative characteristics,

for another thing, early music

pre-supposes improvisatory ability

in the performers, not only in the

realization of the accompaniment

from the figured bass, but to a far

greater degree in the fashioning

of the melodic line. There are

numerous theoretical examples

illustrating the art of

ornamentation as practised in

earlier times, but it is far less

common to discover complete works

with all the ornamentation

appertaining to them, and to be

able to apply them in performance.

The source material is often

scattered throughout the world,

and assembling it requires an

immense amount of patient labour.

The present recording is a living

example of this.

Both Tartini and Nardini were

praised especially by their

contemporaries for their inspired

playing of Adagios, by which is

meant principally not the use of

particular techniques of dynamics,

tone colouration or vibrato, but

the art of decorating the simple

melodies of slow movements and

giving them fresh nuances of

meaning. In the Works of both

composers there are written-out

examples of how this principle was

put into practice - the task was

to locate them.

The earliest work in this

recording is the Concerto in G

major, dating from the middle

period of Tartini’s creative

career. The library of the

Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in

Vienna possesses a complete set of

manuscript orchestral parts of

this work, from which it may be

concluded that they were used at

the concerts given in Prague

during 1724 to mark the coronation

of the Emperor Charles VI. A

noteworthy fact is the careful

marking of parts for the

first-desk artists playing

together with the soloist, in

comparison with the rest of the

parts reserved for the musicians

who joined in only the tutti

passages. The solo part contains

an ornamented version of the slow

movement, so only the cadenzas

were needed for our recording, and

these were taken from Tartini’s Traité

des agréments.

Far more difficult was the task of

reconstructing the Concerto in D

major which, with its themes based

on broken triads, probably belongs

to Tartini‘s last period of

creative activity. Two authentic

scores are in existence: one in

the archives of the Capella S.

Antoniana in Padua, the other in

the library of the Paris

Conservatoire. This work, with its

use of wind instruments and

divided strings in the Padua

score, seems to occupy a special

place among Tartini’s many

concertos. The Paris manuscript,

however, contains only a

straightforward string

accompaniment in four parts.

Closer inspection led to the

surprising discovery that in the

Padua score, where the divided

string parts are always written in

the same staves, two different

versions of the accompaniment were

clearly written above one another:

the earlier handwriting gives the

text of the Paris score note for

note, while the later handwriting

provides a richer accompaniment

with the addition of wind

instruments. The harmonies in this

version are sometimes different,

so the two versions cannot have

been used simultaneously.

Evidently the later version with

fuller string accompaniment

together with wind instruments was

simply entered into the score

without the original version being

eliminated. The revision was

probably the work of Tartini’s

pupil and successor at the Capella

S. Antoniana, Meneghini, who is

known to have made arrangements of

other works by Tartini. There

appeared to be no ornamented

version of the slow movement in

existence until, thanks to a

valuable suggestion from Mr. Alan

Tyson and the kind assistance of

M. A. Rosenthal in Oxford, one was

obtained from Berkeley University,

California, where it forms part of

a collection of 18th-century

Italian manuscripts in the

University’s possession.

The Concerto in E flat major by

Nardini is accompanied by strings

and two horns, and the only set of

orchestral parts is the property

of the Gesellschaft der

Musikfreunde in Vienna. Nardini

was summoned to Vienna in 1765 for

the wedding festivities of the

Emperor Joseph II and possibly

played it there; the manuscript

parts remained in Vienna. It has,

however, been necessary to add

short fermatas, transitional

passages, and the capricci. The

latter, as Tartini wrote in his Traité

and as we can see from his own

works and especially from those of

Locatelli, were of considerable

length. (A wellknown example of

this kind of “capriccio” is the

extensive harpsichord cadenza in

Bach’s Fifth Brandenburg

Concerto.) Those recorded here are

from a collection of caprices in

the possession of the Gesellschaft

der Musikfreunde in Vienna, and

their style suggests that they

were probably composed by Nardini

himself. This recording

demonstrates not only the

evolution of the solo concerto of

the Padua school (Tartini and his

pupils), but also the richness of

the ancient art of ornamentation,

reproduced from authentic sources.

Nardini’s Sonata in D major was

first printed by Cartier in 1798

with reference to an older edition

from 1760. This particular sonata

appeared in Cartier’s collection

with six others “avec les Adagios

brodés”, that is to say with a

very frugal version of each

introductory adagio and a richly

embellished one printed above it.

These embellishments probably

represent the high point of this

development in the 18th century,

which often went beyond the limits

of good taste. Nardini, however,

does not try to outdo his tutor

Tartini in any conceivable way, as

can be seen from the embellished

slow movements he prepared. It is

the duty of a musician not to lose

sight of the poetical content and

musical cohesion of a piece of

music despite the rich scroll-work

it may have, and above all not to

make the embellishments a virtuoso

end in themselves, but to employ

them as an amplification

ofexpression. In the adagio we

have presented the simple version,

reserving the elaborated one for

the repetition. At the cadenza

fermata between the first and

second allegros we have inserted

stylistically authentic examples

from the collection of 246 Fantasie

e Cadenze by Bartolomeo

Campagnoli (1751-1827), a pupil of

Nardini’s.

In closing, a few remarks about

the instruments: The Capella

Academica plays valuable Italian

and German instruments belonging

to the Akademie für Musik in

Vienna. They correspond to

18th-century principles of

construction with their short

necks, thinner bass bars and

differently shaped bridges; these

instruments are played with bows

of corresponding design, which are

held in the Italian manner, above

the nut. The wind instruments,

too, are originals, the horns

belonging to the Haydn Orchestra

in Eisenstadt and kindly lent by

the Provincial Government of the

Burgenland; the oboe, which is the

property of H. G. Stradner, was

made by A. Grenser (1720-1807).

The violin, built by André Klotz

in 1760, has been maintained in

its original form, and with its

still short neck slightly set

back, the lengthened fingerboard

and narrow bass bar. It represents

the classical type of violin as we

know it from Mozart’s original

violin, which can be seen today in

the Mozarteum at Salzburg. This

type most probably also

corresponds to Tartini’s and

Nardini’s instruments, of which

one (although now altered) is kept

at Piran. The bow, which is

extremely light, is thin and bent

inwardly and has an elegant

swan-neck tip. It has its

counterpart in the bows used by

Tartini which still exist in the

Conservatorio “Giuseppe Tartini”

in Trieste. However, as important

as the instrument as such is the

manner in which it is handled, and

here we can see a particular

preference for the light manner of

holding the bow in the so-called

“Italian” style of the

18th-century, which is similar to

the present day’s with the

exception that the bow is held a

bit further up away from the frog.

Another preference is a

concentration of movement in the

flexibility of the wrist, as

opposed to more than a necessary

minimum of movement of the arm

itself.

We chose continuo instruments to

suit the violin: the cello from

Santo Seraphin (in contrast to the

violin, however, it had not

survived unaltered, but has only

been restored to its original

state), the positive organ with

its typical registration (8'

Gedackt, 4' Principal, 2' and 1'

stops) and the two-manual Kirckman

harpsichord. In the case of the

Nardini sonata we thought it

appropriate to use the “piano” of

the later 18th century, the

fortepiano, as an accompanying

instrument; it was just then

beginning to compete with the

harpsichord in this function. The

connection of Nardini’s

composition with Classicism is

thereby emphasized; at the same

time the difference between the

customary sound of today’s violin

and grand piano and the sonority

of the two historical instruments

is underlined.

The concert pitch adopted in

Vienna in former times seems to

have been higher than in other

musical centres - as it is today -

so that it almost corresponded to

our modern pitch. This fact is

proved by a number of wind

instruments of the period which

have come down to us with two

tuning pieces of different

lengths, the shorter of which

enables the instrument to play at

almost exactly present-day pitch.

The instruments of the Capella

Academica are therefore tuned to

a’ = 440.

Eduard

Melkus (1967/72)

(Translated

from the German)

|

|

|

|