|

|

2 LP's

- 139 332/33 - (p) 1969

|

|

| 10 CD's

- 429 042-2 - (c) 1989 |

|

| GUSTAV

MAHLER (1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Long Playing 1 -

139 332

|

|

40' 14" |

|

| Symphonie Nr. 2

c-moll "Auferstehungs-Symphonie" |

|

76' 12" |

|

| - 1. Allegro

maestoso |

19' 36" |

|

|

| - 2. Andante

moderato |

10' 32" |

|

|

| - 3. In ruhig

fliessender Bewegung |

10' 06" |

|

|

Long Playing 2 -

139 333

|

|

35' 58" |

|

| - 4. "Urlicht"

(Altsolo aus "Des Knaben

Wunderhorn") - Sehr feierlich,

aber schlicht - attacca: |

4' 56" |

|

|

| - 5. Im Tempo des

Scherzos. Wild herausfahrend -

Allegro energico |

17' 32" |

|

|

| - 5 (2. Teil):

Langsam. Misterioso (Sopran- und

Altsoli, Chor nach Klopstocks Hymne

"Die Auferstehung") |

13' 30" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Edith Mathis, Sopran

|

|

Norma Procter, Alt

|

|

| Chor des Bayerischen

Rundfunks / Wolfgang Schubert, Chorus

Master |

|

| Fernorchester /

Otto Freudenthal, Leitung |

|

| Symphonie-Orchester

des Bayerischen Rundfunks |

|

| Rafael KUBELIK |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Herkules-Saal.

München (Germania) - febbraio

& marzo 1969 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

Wilfried

Daenicke |

|

|

Recording

Producer

|

|

Hans

Weber

|

|

|

Balance

Engineer

|

|

Heinz

Wildhagen |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon - 139 332/33 - (2 LP's)

- durata 40' 14" & 35' 58" -

(p) 1969 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon - 429 042-2 - (10 CD's

- 2°) - (c) 1989 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

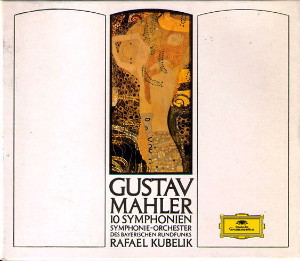

Cover: Gustav

Klimt "Der Kuss" (Detail),

Österreichische Galerie Wien |

|

|

|

|

The Second

Symphony is, together with

"Das Lied von der Erde",

Mahler's most succesful and

most frequently performed

composition. He is said to

have spent seven years

working on this, is most

popular Symphony, which also

gave him the most trouble.

As it was completed in 1894,

its ideas must have been

conceived while Mahler was

still working on the First

Symphony. There is in fact a

close association of ideas

between the two works, not

only because here, as there,

the flow of ideas strives

towards transfiguration and

brightness, but above all

because each of the two

works has as its starting

point the lyrical world of

song. Just as the First

Symphony had its origins in

the song cycle "Lieder eines

fahrenden Gesellen",

individual movements of the

Second, Third and Fourth

Symphonies derive from

settings of poems from "Des

Knaben Wunderhorn".

Despite this blood

relationship, which is

reflected in form and idea,

both form and idea have

undergone a significant

evolution. In the First

Symphony iy was the

"beautiful world", the world

of tangible things, however

poetic they are, in whose

certain possession the

questing spirit rejoiced

after overcoming all errors

and perplexities. The Second

Symphony strives towards the

transcendental, a state of

bliss to be attained only

through overcoming and

departing from the reality

of the beautiful orld. "I

shall die, that I may live"

is its motto.

In the First Symphony the

melodies of songs appear in

purely instrumental

versions, but in the Second

the words are introduced to

enhance the expressiveness

and meaning of the music.

The first movement is in C

minor, and the composer

appears to have placed

particular importance on the

choice of this key, he

assails the listener's cars

with it so intensely and

with such impassioned

vehemence. It is Beethoven's

C minor on which Mahler

insists so emphatically, the

C minor of Beethoven's

"Destiny" Symphony, because

the thoughts of destiny,

fate, and carthly tragedy

give this movement, too, its

immense tension.

From the formal viewpoint

the opening movement of this

Symphony is, perhaps, the

most strictly organized

which Mahler ever wrote. It

is not difficult to

recognize the principal

features of classical sonata

form - the solemn, sombre

and threateningly rising

principal subject, the

slender, attractive form of

the lyrical theme, the

broadly conceived exposition

of these two themes, the

supplementary motives and

motive links which draw them

together, their dramatic

confrontation in a mighty

development section, whose

culmination explodes in a

triple forte and leads to

the Recapitulation. The

shortened form of the

Recapitulation is, if

anything, even more harsh

and forthright than the

Exposition: fate is

relentless, this conclusion

seems to say. The trumpets

play a gentle C major chord,

which seems to float in the

air, as through trying to

bring a note of consolation

into the music, but the

major third is pressed

pitilessly down a semitone,

so that C major becomes C

minor, and the "destiny" key

remains ruthlessly in

command.

The ideological connection

between this movement and

the remaining parts of the

Symphony is unquestionable.

Nevertheless these other

movements belong to a

different sphere, and before

we enter in the composer

asks for a break of a least

five minutes, so that the

tragic C minor which he has

hammered into us can die

away in our minds.

After the first movement

The four remaining movements

of this five-movement work

rise to progressively higher

and freer regions of

existence. The contrast

between them and the first

movement is enough in itself

to create a sense of

liberation. At the beginning

of the graceful, dancelike

and happily melodious

Andante moderato the

oppressive burden has been

cast off for ever. Mahler

wrote in a letter about his

discovery of the

"resurrection" verses by

Klopstock which give the

Finale, and thus the whole

work, its meaning: "The last

movement of my Secon

Symphony meant so much to me

that I searched through

really the whole of the

world's literature, right

back to the Bible, trying to

find the right words of

release ... The manner in

which I received the impulse

for this has a profund

bearing on the nature of

artistic creation. At that

time I had long carried

within me the idea of

introducing a chorus in the

last movement, and only the

fear that this would be

considered a superficial

imitation of Beethoven

caused me to hesitate again

and again. At that time

Bülow die, and I attended

his funeral here in Hamburg.

The choir and organ intoned

Klopstock's hymn

"Auferstehen!" ("Rise up").

It struck me like a flash of

lightning and everything was

suddenly clear to my mind's

eye. This lightning flash

provided the impulse for the

creative process - that is

the divine conception of

art. What I experienced

then, I had to express in

music. And yet if I had not

already has this work within

me - how could I have

received that experience?

There were thousands sitting

with me in the church at

that moment! That is what I

always find: only when I

experience do I compose -

and when I compose I

experience!"

Although this statement of

Mahler's suggests a

speculative interpretation

of his music, we should

regard the speculation as no

more than a general

indication of the direction

in which his thoughts were

running. The artistic

characteristics of the inner

movements of the Second

Symphony make them masterly

examples of absolute music.

They consist not of

philosophical utterances but

of spontaneous music making.

The first of them is the

charming A flat major

Andante in three-eight time,

a movement which cajoles the

ear, a splendid example of

virtuoso instrumentation and

finely calculated musical

relationships.

This brilliant example of

orchestral virtuosity is

followed by a second, also

in three-eight time. The key

is again C minor, but it has

nothing in common with the

sombre C minor of the first

movement. On the contrary,

the way in which the

timpani, bassoons and

clarinets in their low

register set the rhythm

shows from the outset that

this is a cheerful, witty

scherzo in the minor. It is

a symphonic augmentation of

the "Wunderhorn" song about

St. Anthony preaching to the

fishes. The movement flows

calmly along, without break

or interruption, a perpetuum

mobile rich in musical

finesse and delights, and at

the same time vividly

illustrative, as we really

seem to see the fishes

swimming along, mouths open,

to hear sermon.

A fresh, happy-sounding

Intermezzo is inserted, not

interrupting the momentum

but introducting a note of

tender feeling. The sermon

to the fishes is concerned

with the senselessness of

worldly desires and

activities, but the

heartfelt nature of this

interlude restores meaning

and significance to the

whole.

The fourth movement then

follows - without any break,

according to a diretion in

the score. The instrumental

paraphrase of the sermon to

the fishes is followed by a

setting of a "Wunderhorn"

song which is profoundly

meaningful both in its music

and in the words of the

poem. Words and music are of

moving simplicity, having

the deep meaning of

childlike naivety. "I come

from God, and to God will

return" the soul sings at

the gateway to heaven, not

allowing itself to be turned

away, confident in the

knowledge that light -

primeval light - has been

granted to it.

This creates a link with the

idea underlying the fifth

and last movement, which now

follows, also without a

break. We do not hear a

triumphant finale to

conclude the Symphony, but

are witnesses to a musical

drama in which the meaning

of the Symphony is revealed.

We hear mysterious fanfares

from near and far, then

passages of instrumental

finale music; we hear the

voice of the herald in the

wilderness, and the

shattering sounds of the

great call. The resurrection

hymn opens very softly, but

gradually rises in power

until it is an overwhelming

manifestation of faith and

confidence: "Ishall die,

that I mau live."

Heinrich

Kralik

|

|