|

|

1 LP -

139 339 - (p) 1968

|

|

| 10 CD's

- 429 042-2 - (c) 1989 |

|

| GUSTAV

MAHLER (1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symphonie Nr. 4

G-dur

|

|

51' 50" |

|

| - 1. Bedächtig.

Nicht eilen |

15' 47" |

|

|

| - 2. In gemächlicher

Bewegung. Ohne Hast |

9' 04" |

|

|

| - 3. Ruhevoll |

18' 47" |

|

|

| -

4. Sehr behaglich. (Sopransolo: Wir

geniessen die himmlischen Freuden) |

8' 01" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Elsie Morison, Sopran |

|

| Symphonie-Orchester

des Bayerischen Rundfunks |

|

| Rudolf Koeckert, Violin-Solo |

|

| Rafael KUBELIK |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Herkules-Saal,

München (Germania) - aprile 1968 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

Otto

Gerdes |

|

|

Recording

Producer

|

|

Hans

Weber |

|

|

Balance

Engineer

|

|

Heinz

Wildhagen |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon - 139 339 - (1 LP) -

durata 51' 50" - (p) 1968 -

Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon - 429 042-2 - (10

CD's - 5°) - (c) 1989 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

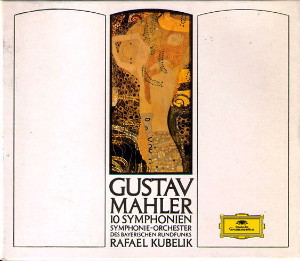

Illustration

auf der Plattentaschenvorderseite:

"Obsgarten mit Rosen", Gemälde

(Ausschnitt) von Gustav Klimt,

Privatbesitz |

|

|

|

|

Close though

the Third and Fourth

Symphonies are to one

another, both musically and

in content, a signifcant

evolution of the composer

lay between them. A year

after the completion of the

Third Symphony Mahler was

appointed to Vienna, as

musical director of the

Court Opera. He saw the

appointment as a most

impressive recognition of

his aims and achievements as

an interpretative musician,

and in addition he felt

confirmed in his calling as

a composer. His

consciousness of matured

artistic and creative powers

filled him with inner joy.

In this agreable state of

peace within himself he

wrote his Fourth Symphony.

By comparison with the Third

Symphony, the Fourth sounds

almost like chamber music.

The themes, too, take on

almost chamber music forms.

The principal theme itself

suggests the character of a

pre-romantic sonata subject;

it has no dynamic power or

phatos. Possibly the

uncommon charm of this

Symphony's opening lies in

the fact that the composer

leaves open the question

whether he is in earnest or

joking, whether his play

with musical figures

represents reality or

illusion.

Again the lyrical theme

which brings its cantabile

character so wilfully to the

fore is in a similar sense

enigmatic, as though it

really wanted not to give

expression, but to play

at expressing. The same is

true of all the secondary

and subsidiary subjects. All

move or bustle along with

the same trimness and poise

of manner which may be

either genuine or assumed.

From the viewpoint of

technical construction this

movement reveals the hand of

a master, a highly skilled

craftsman. Behind it we

sense his enjoyment in

assembling his elaborate toy

and setting it in motion,

its figures interweaving in

apparent confusion, yet in

fact so well controlled that

at the end they are once

again standing in good

order.

The second movement, the

Scherzo, takes its subject -

death strikes up a tune -

none too seriously.

Certainly this is a weird,

fantastic pieces, but its

portrayal of death in less

macabre than grotesque, less

sinister than parodistic.

Mahler instructed that the

strings of the solo violin

on which these tunes are

played should be tuned a

tone higher than usual. He

thus created a uniquely

shrill, pinched tone, which

sounds not only uncommon but

unreal.

With the slow mouvement

there begins the ascent to

higher regions. Not really

ascent, but elevation. We do

not climb, but are raised

up. However, in order to

prevent the listener from

becoming a little too

serious and solemn the

composer inserts some

unquestionably cheerful

variations, creates an

unexpectedly agreable

atmosphere; the theme is

presented in the garb of

folksong, then as a

decorous, light-footed

Allegretto, and finally, in

a broad crescendo, as a

whirling Allegro. After this

outburst of gaiety a single

stroke re-established the

mood of the opening.

At the end of the first and

second movements we could

ask the question whether the

composer was in earnest, or

whether he was merely

playing with the charming

ideas and figures he had

conjured up. In the fourth

movement, and probably in

the third as well, there is

no place for such questions.

Every note shows clearly

that Mahler was completely

sincere in his concept of

the innocence of childhood

expressed in this

music.

Heinrich

Kralik

|

|