|

|

2 LP's

- 139 341/42 - (p) 1969

|

|

| 10 CD's

- 423 042-2 - (c) 1989 |

|

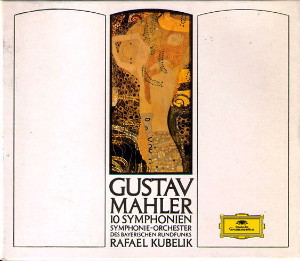

| GUSTAV

MAHLER (1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Long Playing 1 -

139 341 |

|

47' 27" |

|

Symphonie

Nr. 6 a-moll

|

|

74' 05" |

|

| -

1. Allegro energico, ma non troppo.

Heftig, aber markig |

21' 07" |

|

|

| - 2. Scherzo.

Wuchtig |

11' 41" |

|

|

| -

3. Andante moderato |

14' 39" |

|

|

Long Playing 2 -

139 342

|

|

50' 34" |

|

| -

3. Andante moderato |

26' 38" |

|

|

| Adagio

aus der Symphonie Nr. 10 |

|

23' 56" |

|

| -

Andante - Adagio |

23' 56" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphonie-Orchester

des Bayerischen Rundfunks |

|

| Rafael KUBELIK |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Herkules-Saal,

München (Germania):

- dicembre 1968 (Symphonie Nr. 6)

- aprile 1968 (Symphonie Nr. 10) |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Executive

Producers |

|

Otto

Gerdes (Symphonie Nr. 10),

Wilfried Daenicke (Symphonie Nr.

6) |

|

|

Recording

Producer

|

|

Hans

Weber |

|

|

Balance

Engineer

|

|

Heinz

Wildhagen |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon - 139 341/42 - (2 LP's)

- durata 47' 27" & 50' 34" -

(p) 1969 - Analogico |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon - 429 042-2 - (10

CD's - 4°, 2: Symphonie Nr. 10;

7°: Symphonie Nr. 6) - (c) 1989

- ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Stylistically

speaking, Mahler's Sixth

Symphony has much in

common with the Fifth which

preceded it, and with the

Seventh which followed. Like

them it is a work of purely

instrumental character,

whose concept derived solely

from the forces, ideas and

impulses of the musical

texture. The form is marked

by a return to the

traditional layout in four

movements: Allegro, Scherzo,

Andante and Finale. However,

the subject matter with

which Mahler filled the

customary structure has

little in common with the

purpose and nature of

earlier symphonies. It may,

in fact, be said that in his

Sixth Symphony Mahler moved

further than on any other

occasion away from music

making in the accepted

sense. The Sixth is his most

radical Symphony - and

possibly also hit most

personal, since in this work

he revealed the dark side of

his nature with complete

candour. With every note he

wrote Mahle was speaking

from the depths of his

being. The Sixth Symphony is

more than a personal

confession: it is the

surrender and stripping bare

of the composer's innermost

self.

As regards musical

technique, too, this work

stands at the most extreme

point of its composer's line

of development. It is his

most musically audacious and

most modern work, and

possibly, consciously or

unconsciously, Mahler's

questing and exploring mind

had already become subject

to the impetuous forces

which were soon to bring

about a revolution in music.

Mahler 'was not by any means

a pessimist. His symphonies,

which provide the best and

most unambigupus clues to

his attitude to life, give

us a message of hope - all

except one. All conclude in

the major - with the

exception of this Sixth

Symphony. Even "Das Lied von

der Erde" and the Ninth

Symphony, which he wrote

when fearfully aware of the

heart disease which

threatened his life, end

consolingly. Not with

resignation or bitterness,

but with a gentle, benign

gaze back at the beloved

earth.

The Sixth Symphony is known

as the "Tragic", a

description said to heve

been given to it by Mahler

himself. But whence came the

urge to express himself in

such tragic terms? It would

be pointless to speculate

about this, because while

there are probably certain

analogies - sometimes even

evident parallels - between

a creative artist's

experiences and what he

reveals outwardly in his

work, they exist in a remote

spere far removed from the

known worlds.

In such a way the idea of

tragedy itself may have

given Mahler the subject for

his Sixth Symphony - an idea

deep within him which strove

to find expression, without

the impulse of any external

event. This portrayal of

tragedy may have become so

wholly black, hopelest

anguished and oppressive

precisely because the motifs

from which it evolved derive

exclusively from artistic

observation.

If this interpretation is

correct and the Sixth

Symphony, the Tragic, is

indeed the objective

presentation of an idea, an

abstract concept, Mahler

seems at the same time to

have experienced this

realization of the idea as

something with which he

identified himself humanly

and personally. He seems to

have felt within himself the

sense of tragic dread

captured in his music. Owing

to the uncommon sensitivity

of his nature, the inward

experience even affected him

physically.

Alma Mahler has given a

really moving account of the

world première of this

Symphony, which took place

during a music festival at

Essen in 1906. She wrote of

the final rehearsals: "The

last movement of this work

with the three great blows

of fate! No other work so

affected him at first

hearing ... At the

performance Mahler conducted

the Symphony almost badly,

because he was ashamed of

his agitation, and because

he was afraid that his

emotions might get out of

hand while he was

conducting. He did not want

anyone to guess at the truth

of this dreadful anticipando

movement!"

The term "anticipando

movement" evidently implies

that during the year of this

work's composition Mahler

anticipated, in artistic

sublimation, the experience

which was in fact to become

all too real and shattering

three years later, when a

doctor dicovered that he was

suffering from a grave heart

disease, and he regarded the

diagnosis as a sentence of

death.

A fact which appears purely

superficial sheds further

light on the sombre mystery

of the Sixth Symphony. In

this work Mahler added to

his already massive

orchestra two further

instruments, or more

correctly noise-producing

implements: cowbells and a

hammer. Both are of

symbolical significance.

Mahler himself is said to

have remarked that the

cowbells represent the last

sounds heard from the earth

by a lone wanderer as he

ascends to the heights, so

that they symbolize complete

isolation, as though remote

from the world. The meaning

of the hammer is not

difficult to guess; mention

has already been made in a

quotation of the "three

great blows of fate". Mahler

wrote that the hammer was to

produce a short, strong but

dull-sounding thud, not

metallic in character. When

the hammer stroke occurs,

however, the event which is

intended in a symbolic sense

becomes crudely realistic:

fate does not knock at the

door but opens it by force,

and appears on the symphonic

stage in a tangicle

personification.

In any event these newly

introduced tonal symbols

serve as indications of the

direction in which to look

for clues to the meaning of

the individual movements.

When the cowbells are heard

in the first movement, they

suggest that the lone

wanderer has reached the

highest summit and the most

remote region. Viewed from

this point, it is evident

that the whole tremendous

movement represents a

struggle upwards, impelled

by wild, demoniac passions.

The two central movements,

Andante and Scherzo,

represent different stages

en route, but they bring

neither diversion, repose or

relaxation. The Andante

begins almost in the manner

of the Adagietto from the

Fifth Symphony, but meither

the sense of disquiet as it

develops, nor its tortured

harmonies, allow this

movement to sing

consolingly. The Scherzo

gives the impression that it

is compelling itself by an

effort of will not to dwell

on sombre, threatening and

evil thoughts. Artificial

poses are adopted, so that

the music sounds

intentionally affected.

Mahler gave here the express

direction "altväterisch"

(antiquated). This is both

an indication of tempo and

manner of performance, and a

clue to the underlying

meaning of the music.

The term Finale is

inappropriate to the fourth

and last movement, since

this is the heart, and

principal section, of the

entire work. Not only in

externals and as regards its

dimensions does it tower

over all that has gone

before: its significance is

such that it makes the

preceding movements its

forerunners, preludes or

satellites. This movement,

with its wild and despairing

struggle upwards, has no

real need of the hammer as a

symbolical instrument, so

powerful and inexorable are

the feeling and

consciousness of tragedy

which it creates in

the listener - a sense of

our absolute impotence when

confronted by the dark and

evil forces of destiny.

· · · · ·

Among the

papers left by Mahler at his

death was a black folder

containing sketches for his

Tenth Symphony. Some

sections of the work had

already taken on tangible

form, so that many

significant features were

apprecciable, giving some

idea of the basic outlines

of the projected

composition. According to

Alma Maria Mahler, the

fundamental feeling of the

Tenth Symphony is the

certainty and suffering of

death, together with

defiance of death. Looking

through the sketches, one

does indeed sense the

presence of a feeling that

death is near.

The first movement is an

Adagio whose mood is one of

resignation. A broadly-spun

melody seems to stretch out

its arms to embrace the

whole world once again

before darkness closes in. A

fifteen-bar Introduction is

played by the violas alone.

Motto-like, it recurs

several times during the

course of the movement, in

slightly varied form. The

principal theme of the

Adagio is rich in wide

intervals, which enhance its

expressive character to a

remarkable degree. Trills

and pizzicato fidures create

a strange sense of holding

back. The alternation

between smooth-flowing

animation and sudden

hesitations, or an apparent

complete cessation of

momentum, so typical of

Mahler, gives this movement

its unmistakable character.

The Adagio is the only

movement which Mahler

completed in almost every

detail. It gives the

listener an impression of

overall unity, even though

he may sense the existence

of gaps, and of passages

whose meaning is veiled or

which lack final touches.

According to the sketches

the Finale would have been

related in mood and thematic

material to this first

movement.

Heinrich

Kralik

|

|