|

|

2 LP's

- 2707 038 - (p) 1967

|

|

| 10 CD's

- 429 042-2 - (c) 1989 |

|

| GUSTAV

MAHLER (1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symphonie Nr. 9

D-dur

|

|

77' 01" |

|

Long Playing 1 -

139 345

|

|

|

|

| -

1. Satz: Andante comodo |

25'

57" |

|

|

| -

2. Satz: Im Tempo eines gemächlichen

Ländlers. Etwas täppisch und sehr

derb |

16' 01" |

|

|

Long Playing 2 -

139 346

|

|

|

|

| -

3. Satz: Rondo. Burleske. Allegro

assai. sehr trotzig |

13' 17" |

|

|

| -

4. Satz: Adagio. Sehr langsam und

noch zurüchhaltend |

21' 46" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphonie-Orchester

des Bayerischen Rundfunks |

|

| Rafael KUBELIK |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Herkules-Saal,

München (Germania) - febbraio

& marzo 1967 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

Otto

Gerdes

|

|

|

Artistic

Supervision

|

|

Hans

Weber |

|

|

Recording

Engineer

|

|

Heinz

Wildhagen |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon - 2707 038 - (2 LP's) -

durata 41' 58" & 35' 03" - (p)

1967 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon - 429 042-2 - (10

CD's - 10°) - (c) 1989 - ADD

|

|

|

Note |

|

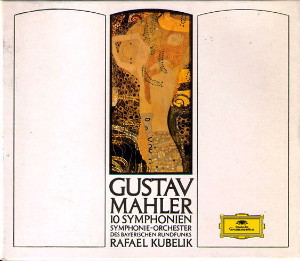

Illustration auf

der Taschenvorderseite: "Die

Erwartung", Gemälde von Gustav

Klimt )Entwurf zum

Stoclet-Fries, Ausschnitt),

Österreichische Museum für

Angewandte Kunst, Wien

|

|

|

|

|

The 9th

Symphony, Mahlet’s last

completed work, dates from

the summer of 1909, and it

forms a link between

romantic.and modern music.

The customary symphonic

layout is abandoned;

two slow movements enclose

two scherzo-like interludes.

None of the movements ate in

traditional

sonata form: in the first

movement the variation

principle outweighs the

rudiments of sonata form,

the second movement is a

succession of dance themes,

while the third and fourth

are fashioned as

rondos. There is no longer

any harmonic common

denominator: the Symphony

begins in D major

and ends in D flat major,

while the interludes are in

C major and in Mahler’s

tragic key of A

minor. The symphonic texture

is no longer governed by the

vertical, harmonic principle

but by the

linear, horizontal shaping

of independent instrumental

voices, resulting in sounds

and clashes

which suggest early

Schoenberg. The

instrumentation follows this

free polyphony in a wholly

unorthodox manner; there ate

tonal mixtures of highly

expressive originality,

audacious overlappings and

exciting new combinations of

sounds. The Ninth has its

roots in the 19th century,

but its

most significant features

point forward to modern

developments.

Mahler dreaded the ominous

number nine in connection

with symphonies, owing to

the fact that

Beethoven, Schubert and

Bruckner had all died after

writing their ninth

symphonies. Mahler gave

his own real ninth, the

vocal Symphony after Chinese

texts, the oratorio-like

title “The Song of the

Earth”. The mood of farewell

at the end of this vocal

work leads to the sense of

resignation which

is the basic characteristic

of the Ninth Symphony.

Certain note sequences and

motives from “The

Song of the Earth” reappear

in veiled forms, pointing to

the inner connection between

the two

works. Bruno Walter, who

conducted the world

premiéres of both of them

after Mahler’s death,

was the first person to

point out the relationship

which exists between them,

with the Ninth carrying

forward and enhancing the

basic themes of ““The Song

of the Earth”’: farewell,

resignation, and

death.

The first movement, an

Andante comodo in D major,

flows as a single, broad

stream of sound, and

is basically a vast melodic

arch-extending over 60 pages

of score. The principal

melody in the

major, which begins at bar

6, bears the entire weight

of the movements’ diverse

structure; it is

varied rather than developed

in the academic sense, a

veiled variant in the minor

forming the

second subject. The

principal theme rises to

climaxes and undergoes

compression, is

recapitulated,

and leads to a Coda which

dies softly away. Elements

of sonata form and of the

variation principle

are interwoven. Adorno sees

in the Andante an

“‘all-embracing antithesis”;

question and answer

ate intermingled. “The

instrumental voices vie with

one another as though each

were trying to

dominate and outbid the

others; hence the limitless

expressiveness of this

piece, and its resemblance

to speech. The themes are

neither active nor passive,

but arise as though, while

speaking, the music

receives fresh impulses

which prompt it to speak

further.”

The second movement begins

in C major, “In the tempo of

a relaxed landler”’. From

the outset the

atmosphere of a dance of

death lies over this Scherzo

based on the technique of

development. Its

second thematic group is a

quick Waltz in E major, and

its third part introduces a

slow landler in

F major. The

Development-like middle

section transforms the

Waltz, interrupted by

reminiscences

of the other thematic

groups. As a kind of

Recapitulation the first

landler returns,

interspersed by

motives from the other

themes. The strangeness of

this montage of dance tunes

is underlined by

bizarre instrumentation: the

second violins pound out the

C major theme “clumsily,

like peasant

fiddles’’, trombones

introduce an ominous element

into the Waltz, and

intentionally crude, vulgar

turns of phrase are churned

out sarcastically, until the

orchestra sounds like an

enormous barrelorgan.

Mahlet’s witches’ sabbath.

The thematic germs of the

third movement shoot up

“very defiantly” from the

strings and brass;

this Rondo-Burlesque in A

minor is dedicated with

bitter irony “to my

Apollonian brothers”.

“This piece, too, is a

backward glance over the

composet’s life with its

preoccupations, in which the

song of creative endeavour

re-echoes as something

grotesquely distorted. The

artist is mocking himself.

This is biting contempt for

the world, but it is born of

profound tragedy” (Paul

Bekker). The

Development-like

transformations of the

subject matter lead into a

brusque fugato. A further

section, marked “with great

feeling” and in the D major

tonality in which the

Symphony opened,

is a lyrical passage for the

violins, already pointing

forward thematically to the

great songlike

theme of the Finale. A

repetition of the first

subject culminates in a

demoniac stretta. Extented

to

gigantic stature by

augmentation, its sforzati,

wind trills and emphatic

grace notes create the

atmosphere of the “Drinking

song of Earth’s sadness

”’from “The Song of the

Earth” - a harsh vision of

annihilation.

The concluding Adagio in D

flat major, which begins

after a short, impassioned

recitative as a

sonorous song of the

strings, heightens the

atmosphere of the first

movement to the level of the

sublime. Twice the song is

interrupted as in a rondo,

by episodes whose

contrapuntal texture derives

from the bassoon theme which

has intruded like a sombre

exclamation after the D flat

major

cantilena.

The principal theme, in

which Schubert seems to

encounter “Tristan”, forms

the basis

of the final melody, which

is woven “with inward

feeling” upon the D flat

major chord of the

strings, dying away “ppp”. A

release from earthly things,

farewell, and

transfiguration. Mahler’s

Ninth Symphony concludes

with tranquil harmonies; his

Tenth remained incomplete.

Barely two

years later Mahler succumbed

to a heart disease. In 1912,

a year after Mahler’s death,

Bruno Walter

conducted the world premiére

of the Ninth Symphony in

Vienna.

Karl

Schumann

|

|